- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 8. Dezember 2022

Inhalt

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Heuristic definition of betrayal

- 3. The relation between betrayal and the heroic

- 4. Historical case study: heroization and betrayal during the First World War

- 5. Historical case study: from hero to traitor – Philippe Pétain

- 6. Perspectives

- 7. Einzelnachweise

- 8. Selected literature

- 9. List of images

- Citation

1. Introduction

A betrayal is an act committed by one or more agents that a community either judges to be morally an abuse of its trust or that it has defined formally to be a breach of faith.1Javeau, Claude: Anatomie de la trahison. Paris 2007; Schehr, Sébastian: “La trahison. Une perspective sociohistorique sur la transgression en politique”. In: Parlement[s], Revue d’histoire politique 22 (2014), 21-35; Schlink, Bernhard: “Der Verrat”. In: Schröter, Michael (Ed.): Der willkommene Verrat. Beiträge zur Denunziationsforschung. Weilerswist 2007, 1-20; Krischer, André: “Von Judas bis zum Unwort des Jahres 2016. Verrat als Deutungsmuster und seine Deutungsrahmen im Wandel”. In: Frischer, André (Ed.): Verräter. Geschichte eines Deutungsmusters. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2019, 7-44. As a socio-cultural phenomenon, betrayal therefore marks not just the boundaries of a community’s norm and value framework, but also who belongs to that community. The betrayer figure thus becomes part of the field of remembrance in which ⟶heroic figures, ⟶martyrs, victims and villains are constantly the subject of negotiation processes and in competition with one another.2The concept of an ‘imaginary field of the heroic’ allows for insights to be gained into the processes how extraordinary, liminal figures are constructed, and it facilitates the analysis of the underlying social power structure, cf. Gölz, Olmo: “The Imaginary Field of the Heroic. On the Contention between Heroes, Martyrs, Victims and Villains in Collective Memory”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 (2019): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories, 27-38. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/04. Accordingly, the betrayer figure represents not merely a negation of the heroic; rather, the accusation of betrayal also holds a potential to deconstruct heroic figures that can hardly be underestimated.

2. Heuristic definition of betrayal

Although everyday forms of betrayal such as cheating on a partner or snitching on schoolmates are also qualitatively opposed3Bröckling, Ulrich: “Negations of the Heroic – A Typological Essay”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 (2019), 39-43. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/05. to the norm and value framework of a community, the following observations will focus on extraordinary instances of betrayal.

Narratives of betrayal and loyalty shape the collective memory of communities4Ben-Yehuda, Nachman: Betrayals and Treason. Violations of Trust and Loyalty. London 2001; Queyrel-Bottineau, Anne: Trahison et Traîtres dans l’Antiquité: actes du colloque International. Paris 2012; Billore, Maïté: La trahison au Moyen Âge: de la monstruosité au crime politique. Rennes 2009; Tracy, Larissa: Treason: medieval and early modern adultery, betrayal, and shame. Boston / Leiden 2019; Irischer, André: Verräter: Geschichte eines Deutungsmusters. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna; Javeau, Claude / Schehr, Sebastian: La trahison. De l’adultère au crime politique. Paris 2014. across both time and space, and they point to the ambivalent interrelation between the heroic and its negations. While betrayal is regarded as one of the communicative mechanisms that give structure to the ⟶imaginary field of the heroic, in conceptual terms it can be defined as the antithesis of the ⟶heroic deed.5Giesen, Bernhard: Zwischenlagen. Das Außerordentliche als Grund der sozialen Wirklichkeit. Weilerswist 2010. In this sense, betrayal is to be characterised as exceptional because a breach of trust is hardly perceived as an everyday act. The breach of social, cultural or political norms reveals the transgressive character of this act, which has an immense emotional and moral power because it challenges collectively recognised norms. However, unlike the heroic deed, betrayal provokes negative reactions at the moment in which it is perceived by a community as an abuse of confidence or as a breach of trust.6Bröckling: “Negations of the Heroic”, 2019.

Like the heroic deed, in order to become an element of individual and collective interpretations of reality, an act of betrayal must always be embedded in a narrative that suggests coherence. This narrative is characterised by a tripolar structure: the perpetrator(s) of the betrayal, the ‘betrayers’, commit an act of disloyalty against one or more ‘betrayed’. For an act of betrayal to be credibly communicated, there must also be an object for the sake of which the act was committed. This can be another person such as a friend, a tangible thing like a prized possession or an abstract idea like a nation.7Krischer: “Verrat als Deutungsmuster”, 2019, 10; Schehr, Sébastien: “Sociologie de la trahison”. In: Cahiers internationaux de sociologie 123 (2007), 313-323; Schlink: “Verrat“, 2007. The betrayer does not necessarily need to intend to cause harm to their community if they can claim to be serving a higher purpose.8Javeau: “Anatomie de la trahison”, 2014; Schlink: “Verrat“, 2007.

Therefore, whether or not there has been an act of betrayal depends on the moral, political and legal notions of the community, and not least on the specific historical context in which the act is assessed. If that context changes, potentially new room for interpretation opens up in which the act of betrayal can be re-evaluated. Just like heroes, betrayers are also constantly subject to processes of reinterpretation, which means that they can be assessed differently even within the same community. In this tension between complex temporal relations and social ambiguity of the imaginary field of the heroic, different assessment scenarios of transgressive acts play out. Inferences can in turn be drawn from these scenarios about a community’s notions of the socio-cultural and political order.

3. The relation between betrayal and the heroic

Both treacherous and heroic figures transgress the prevailing norm and value framework of a community. Their socio-cultural construction can be understood as boundary work through which the social order is negotiated and actualised constantly.9Giesen, Bernhard: Triumph and Trauma. Boulder 2004, 1-4; Gölz: “Imaginary Field”, 2019. However, in contrast to a heroic deed, social boundaries cannot be lastingly shifted by an act of betrayal. On the contrary, the disloyalty of the betrayer makes the community aware of its violated moral boundaries. The betrayer uniquely symbolises which norm breaks are not tolerated. He stands between the community and ‘the others’, and he appears in the narrative as the one who has left his own group behind and embraced another norm and value framework. In this sense, the betrayer’s ⟶transgression also often has a physical component because it entails the defection to another community. In ideal-typical terms, the betrayer’s own community ends where the act of betrayal is no longer regarded as such.10In this sense, but of course with reverse intent, the betrayer fulfils a similar socio-cultural function to that of the martyr, who symbolises and, to an extent, defines the boundaries between two communities of faith. The concept drawn upon here was developed by Olmo Gölz, whom we would like to thank for the stimulating discussion. See Gölz, Olmo: “Martyrdom and the Struggle for Power. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Martyrdom in the Modern Middle East”. In: Behemoth. A Journal on Civilisation 12.1 (2019), 2-13. Whoever accepts the betrayal also reveals their divergence from the group and risks being excluded from the community as well.

In this context, as a social scapegoat, the betrayer becomes the focal point of collective attributions of blame and personifies traits that a community considers to be negative.11Girard, René: Der Sündenbock. Zurich 1988: Benziger; Viertmann, Christine / Schuppender, Bernd: Der Sündenbock in der öffentlichen Kommunikation. Schuldzuweisungsrituale in der Medienberichterstattung. Wiesbaden 2015: Springer, 35-88. Thus, the figure of the betrayer serves to reduce complexity and create meaning. Betrayal therefore takes on an important unifying function, as the ostracism and condemnation of the betrayer strengthens a community’s cohesion and cements its moral framework. At the same time, the outcast traitor reminds the community that group affiliation does not follow automatically from being born into a community, but is linked to a value system that must be conformed with.12Mock, Steven: Symbols of Defeat in the Construction of National Identity. Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, 215-223.

In the contested imaginary field of the heroic, betrayal and the heroic are therefore in a close dialectical interrelationship with each other. The heroic figure and the treacherous figure mark processes of boundary work because they embody a dichotomous polarisation. They allow for a simple opposition to crystallise out of a complex social situation. Communities can orientate their identity and primarily their affects towards that opposition.13Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero as an Effect. Boundary work in Processes of Heroization”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 (2019), 17-26, 20. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/03.

But what happens when a heroic figure is confronted with accusations of betrayal and this meaning-endowing dichotomy collapses? Such an event presents a community with an exceptional challenge, particularly in moments of dynamic transformation experiences. If heroic figures are perceived as personifications of socially recognised norms, then not only does their being reinterpreted as a betrayer constitute a direct deheroization, the social norm and value framework embodied by the hero is also abruptly subjected to (re)negotiation.

Accusations of betrayal and the breach of trust they imply are particularly serious for heroized actors since it can be assumed that an especially high degree of trust is placed in heroic figures. Heroic figures have their contingency-reducing function not least because of this social resource, which is essential for social cohesion.14Frevert, Ute: Vertrauensfragen. Eine Obsession der Moderne. München 2013: Beck; Frevelt, Ute: “Vertrauen – eine historische Spurensuche”. In: Frevelt, Ute (Ed.): Vertrauen. Historische Annäherungen. Göttingen 2003: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 7-66; Luhmann, Niklas: Vertrauen. Ein Mechanismus der Reduktion sozialer Komplexität. 4th Edition. Stuttgart 2000: Lucius und Lucius; Reemtsma, Jan Philipp: Vertrauen und Gewalt. Versuch über eine besondere Konstellation der Moderne. Hamburg 2008: Hamburger Edition. In the case of a heroized actor, the perceived relationship of trust between the actor and his/her followers is based on the exceptional meaning that is attributed to the hero. Furthermore, the emotional bond between the hero and his/her followers suggests a close reciprocal relationship of loyalty that is constantly substantiated by the heroization. It is irrelevant whether or not this loyalty is real. Through the followers’ belief, it becomes a constitutive element of their interpretation of reality.

Through trust and the loyalty based on it, the heroic figure helps to cope with experiences of contingency and to reduce uncertainties. At the same time, these two social resources structure the expectations of the hero and compel him to act in accordance with them. A heroized agent is expected to not betray the trust of the community and to act loyal to it. If this expectation is not fulfilled, disappointment is evoked, which does not necessarily have to lead to an accusation of betrayal, however. For that to happen, an active deed and a further transgression is necessary that some of the hero’s followers no longer interpret positively. If that happens, an accusation of betrayal is levelled against the heroized agent and their interpretation as a heroic figure is upended. Through the betrayal, the hero becomes a perpetrator. The ensuing deheroization processes are supposed to meaningfully explain the breach of both trust and loyalty, as well as stabilise the collective norm and value framework. Norms that were previously considered certain must now be renegotiated and possibly modified. An act being judged a betrayal marks the collective attempt to confirm normatively the validity of the value framework that the previously heroized figure has transgressed.

However, an act of betrayal can also lead to a transformation in the community of admirers if the action that forms the basis of the accusation of betrayal is interpreted positively. The tripolar narrative between the betrayer, the betrayed and the object of the betrayal being open to interpretation results in not every affected party interpreting the betrayal as such. In this case, a betrayal reveals interpretational struggles in particularly impressive fashion. These struggles are enlightening for social self-interpretations, and they are waged via the ambivalent interrelation between the heroic and betrayal.

4. Historical case study: heroization and betrayal during the First World War

The relation between heroization and betrayal was manifest in particular fashion during the First World War.15Leonhard, Jörn: Der überforderte Frieden. Versailles und die Welt 1918–1923. 2nd Edition. Munich 2019: C.H. Beck, 902-903. The mobilisation of millions of people and the mass casualties put immense strain on the warring societies. From August 1914 onward there were constant calls for solidarity between the frontlines and the home front. However, at the same time, numerous betrayal narratives emerged. Behind it all was the fear that the Burgfrieden truces from summer 1914, rhetorically celebrated time and again, might fall apart in the reality of total war. In Russia, the pivotal year 1917 proved in dramatic fashion what effects polarisation within a society could have and how the heroization of defenders of the fatherland at the military fronts could turn into the intra-societal conflict of a bloody civil war. Hence, under the burden of industrialised mass warfare, the question of everyone’s loyalty intensified.

While many conventional notions of military heroism were called into question by qualitatively and quantitatively novel experiences of war, such as the death of millions and visible invalidity, notions of betrayal developed in all of the warring societies – be it in spies and enemy foreigners or in those individuals who attempted to shirk the burdens of war. Omnipresent, alleged ‘draft dodgers’ and ‘profiteers’ stood in contrast to the heroized war effort of the national communities. The heroization of the combatants at the frontlines or of the labourers and women on the home front were given a particularly suggestive context by referencing alleged betrayers on the home front.

One particularly impressive example of the betrayal motif was Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau’s presentation of the French government’s programme in the Assemblée nationale on 20 November 1917.16Leonhard: Der überforderte Frieden, 2019, 381. During his speech, Clemenceau referred to the link between the home front and the fighting soldier as the core of the heroic nation in war: “One sole and simple duty: stand by the soldier, live, suffer, fight with him. Abstain from all that does not belong to the fatherland”. In emblematically identifying the entire nation with the heroized normal soldier, the poilus, Clemenceau was responding to the crisis of spring 1917, when mass mutinies had occurred on the Western front and, at the same time, there had been strike movements on the home front in France. Clemenceau was now demonstratively acknowledging the French recruits, the labourers in the factories, the farmers in the fields, but also women and children. Above all, he opposed any pacifist stance. Even just the suspicion of defeatism appeared to be a betrayal of the sacrifices and burdens shouldered because of the war: “No pacifist campaigns, no German intrigues any longer. Neither betrayal nor semi-betrayal: war, only war.”17Clemenceau, Georges: Speech of 20 November 1917. Quoted from: Becker, Jean-Jacques: Clemenceau, l’intraitable. Paris 1998: Levi, 134-135 and Winock, Michel: Clemenceau. Paris 2007: Perrin, 426-428; Dallas, Gregor: At the Heart of a Tiger. Clemenceau and His World 1841–1929. London 1993: Carroll & Graf, 501-502.

As the war entered its decisive phase in late summer 1918, such betrayal narratives lost their relevance in the countries of the victors, while in Germany the ‘stab in the back’ metaphor became the most significant explanation for the defeat and the revolution (cf. fig. 1). One year after the dramatic upheaval of defeat and revolution, Paul von Hindenburg, the former head of Germany’s Third Supreme Army Command, testified before the Reichstag’s parliamentary commission of enquiry whose mandate it was to clarify the circumstances surrounding the country’s collapse in autumn 1918. On 18 November 1919, Hindenburg endorsed the narrative of the internal betrayal of the frontline heroes, who were militarily undefeated, by a home front infiltrated according to the example of the Russian Bolsheviks. Hindenburg was drawing upon a comment attributed to the British general Frederick Maurice that had appeared in a December 1918 article of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung and seemed to verify this claim: “An English general rightfully says: ‘The German army was stabbed in the back.’ […] Where the blame lies is clearly evident. If even more proof were needed, then it is in that quoted phrase of the English general and in the boundless astonishment of our enemies at their victory.”18Quoted from: Janz, Oliver: 14. Der große Krieg. Frankfurt a. M. 2013: Campus, 323; Keil, Lars-Broder / Kellerhoff, Sven Felix: Deutsche Legenden. Vom “Dolchstoß” und anderen Mythen der Geschichte. Berlin 2002: Links, 36; Lobenstein-Reichmann, Anja: “Die Dolchstoßlegende. Zur Konstruktion eines sprachlichen Mythos”. In: Muttersprache 112 (2002), 25-41.

Already in spring 1919, against the background of the peace conference taking place in Paris and the persistent instability of the new democratic republic in Germany due to the threat of civil war, this stab-in-the-back motif developed an enormous dynamic as a betrayal narrative. It stood in contrast to the suggested heroism of the frontline soldiers returning home, and, after the war had ended, lent itself to being used against those who were participating in the young republic. In March 1919, the theologist and publicist Ernst Troeltsch discussed how the unique motif of betrayal advanced the polarisation of Germany’s political culture: “Hatred must be fomented in moral terms against the majority; against social democracy with the charge of having destroyed the German Empire; against democracy with the accusation of being Jewish, mammonistic, un-German and international; against both with the catchword ‘antinational’.”19Troeltsch, Ernst: “Links und Rechts (März 1919)”. In: Troeltsch, Ernst: Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Ed. by Friedrich Wilhelm Graf, Christian Albrecht and Gangolf Hübinger. Vol. 14: Spectator-Briefe und Berliner Briefe (1919–1922). Berlin 2015: de Gruyter, 72-78, 76-77.

However, in the societies of the victors as well, betrayal narratives after the war served to distinguish even more clearly between heroization and deheroization. In Belgium for instance, which had been occupied by the Germans since the beginning of the war and experienced all variations of collaboration between the occupiers and the occupied, there was a collective épuration. This process focused on the symbolic purging of all those from the Belgian nation who were accused of betraying the nation during the war.20Leonhard: Der überforderte Frieden, 2019, 591. This violence was directed against actual or alleged war profiteers and speculators, but also repeatedly against those who were accused of collaborating with the German authorities or military. Women who were suspected of having had sexual relations with German soldiers had their heads shaved and were driven through cities and villages for all the public to see – the alleged betrayal corresponded to the ideal of the loyal wife who awaited the return of her husband.21Benvindo, Bruno / Majerus, Benoît: “Belgien zwischen 1914 und 1918. Ein Labor für den totalen Krieg”. In: Bauerkämpfer, Arnd / Julien, Élise (Eds.): Durchhalten! Krieg und Gesellschaft im Vergleich 1914–1918. Göttingen 2010: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 127-148, 145-146.

The punishing of betrayal in the period of épuration enabled at the same time a particularly accentuated heroization of the victims. While the Frenchman Gaston Quien just narrowly escaped a conviction before a military tribunal in Paris in 1919 on charges of having turned over nurse Edith Cavell to the German authorities and thereby being responsible for her conviction and execution, there were several death sentences handed down in Belgium against informants. In light of the collaboration, these emotionally highly charged trials served to substantiate the heroized self-image of a Belgian martyr nation in the war. The publicised and sanctioned betrayal appeared as the reprehensible exception of a small few. Hence, the personalisation of guilt and collective exoneration were also part of the mechanism of heroization and betrayal.22Rousseaux, Xavier / van Ypersele, Laurence: “Leaving the War. Popular Violence and Judicial Repression of ‘Unpatriotic’ Behaviour in Belgium (1918–1921)”. In: European Review of History / Revue européenne d’histoire 12 (2005), 3-22.

These mechanisms fostered a complex transformation of nationalism after the war. This new nationalism entailed intensified exclusion and aggressive revisionism. In several respects, it found its basis in wartime experiences: in casting suspicion against ‘enemy aliens’, supposed ‘defeatists’, ‘traitors’, ‘draft dodgers’ and ‘profiteers’ and in defaming every concession as defeatism and betrayal against the heroized nation and its sacrifices.23Leonhard: Der überforderte Frieden, 2019, 1269.

5. Historical case study: from hero to traitor – Philippe Pétain

The interrelation between heroization and betrayal is particularly evident in the example of Philippe Pétain (1856-1951).24Schubert, Stefan: “The Downfall of a Hero: The Vilification of Philippe Pétain”, in: Saeculum, Special Issue: Villains! Constructing Narratives of Evil (in press). During the First World War, Pétain was one of the commanders of the French troops at the Battle of Verdun in 1916. After the war, he was linked with that emotionally charged place of remembrance through a multilayered heroizing narrative. Pétain also held central military offices and, as a heroized marshal, remained a latent figure of French memory culture regarding the First World War. After France’s defeat against Nazi Germany, he became the head of state (chef d’État) of the Vichy regime in July 1940 and remained in that office until the regime’s end in late summer 1944. In August 1945, he was convicted of treason and banished to the Île d’Yeu, where he spent the remaining six years of his life.25Ferro, Marc: Petain. Paris 1987: Fayard; Pedroncini, Guy: Pétain, le soldat 1914–1940. Paris 1998; Vergez-Chaignon, Bénédicte: Pétain. Paris 2014: Perrin. Partial aspects of the heroization of Pétain and his significance as a political myth are focused on by Servent, Pierre: Le mythe Pétain. Verdun, ou, les tranchées de la mémoire. Paris 1992: Payot and Fischer, Didier: Le mythe Pétain. Paris 2002: Flammarion. The accusations of betrayal levelled against Pétain from the summer of 1940 onward had a deheroizing and delegitimising effect. Pétain’s is a prime example of how this effect can be understood in light of the trust that had been placed in him: trust was particularly important for both the heroic and the treacherous figure that Pétain represented.

The ability to build trust became one of the most important qualities that distinguished the heroic figure Pétain early on26“La confiance du général Pétain”. In: Le Rappel, 18 March 1916., and it would remain such up through the 1940s. In French society, this attribute was associated with further qualities that pointed primarily to an outstanding character: strength of nerve, resolve, willpower and benevolence formed the basis for French soldiers and the entire nation placing their trust in Pétain.27Le Petit Journal. Supplément du dimanche, 16 February 1919: “Après les événements d’avril et de mai 1917, une crise de dépression morale sévit un instant dans l’armée. Pétain s’attacha à relever les volontés abattues, à exalter les âmes. Il visita successivement près d’une centaine de divisions, écoutant les chefs, les officiers, jusqu’aux simples soldats. Et partout, sur son passage, il sut faire vibrer les cœurs et rétablir la confiance.” Ducray, Camille: Le maréchal Pétain. Paris 1919, 20: “Le sol de France est enfin délivré. Pétain a toujours eu confiance dans la valeur de ses soldats, qu’il estime et qu’il aime.” Pétain himself referred to the attribute of trust at numerous public appearances, like he did for example during a speech at the dedication of the memorial to fallen soldiers on Côte 304: “Aux premiers renforts jetés à la tête de l’ennemie et qui s’engageaient dans un combat confus, par un temps épouvantable, j’ai dit d’abord: ‘Confiance!’.” Pétain, Philippe: quoted from L’Echo de Paris, 18 June 1934. These attributions became part of the state cult of personality that was maintained around Pétain during his rule as chef d’État between 1940 and 1944. The fragile political system created a state-bearing ideology that was based essentially on the unifying figure of the head of state.28Lackerstein, Debbie: National regeneration in Vichy France. Ideas and policies, 1930–1944. Farnham 2012: Ashgate; Norton, Mason: “Counter-Revolution? Resisting Vichy and the National Revolution”. In: Dodd, Lindsey / Lees, David (Eds.): Vichy France and everyday life. Confronting the challenges of wartime, 1939–1945. London 2018, 197-211; Paxton, Robert: Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944. New York 1972: Columbia University Press. Pétain himself often legitimised his claim to power using a rhetoric of trust. In as early as his first radio address to the nation as head of state, he swore: “In order to accomplish the immense task ahead of us, I need your trust. Your representatives have given me your trust in your name.”29“Pour accomplir la tâche immense qui nous incombe, j’ai besoin de votre confiance. Vos représentants me l’ont donnée en votre nom.“ Speech from 11 July 1940. In: Pétain, Philippe: Discours aux Français. Paris 1989: Michel, 68. In conformity with this rhetoric, Vichy-conform biographers often called upon the French people to place their trust in the marshal.30Marc-Vincent, P.: De l’armistice a la paix. La France nouvelle, Tome 1. 25 Juin–24 Octobre 1940. Paris 1940: Tallandier, 215: “Pour poursuivre avec dignité ce programme de reconstruction de l’Europe, faisons confiance au Maréchal, qui incarne la France dans ce qu’elle a de plus haut et de plus noble…” This meant the same as trusting the new state system and the ideology of the révolution nationale. Trust was a significant socio-cultural and political resource in Vichy France. In both social and political terms, it proved to be an advance payment, however, that lost value quickly when the expectations that had been created were not fulfilled.

That point was reached for a large part of the French populace by no later than spring 1942. Deheroization processes that had already been evident since the summer of 1940 now developed a new dynamic. The trust in the head of state sank as a result of the regime’s inherent political impotence, the more intensive collaboration and a deteriorating supply situation.31Baruch, Marc-Olivier: Vichy-Regime. Frankreich 1940–1944. Stuttgart 2000: Reclam; Cointet, Michèle: Nouvelle histoire de Vichy (1940–1945). Paris 2011: Fayard; Ferro: “Pétain”, 326-327; Winkler, Heinrich August: Die Zeit der Weltkriege. 1914–1945. 3rd edition. München 2016: Beck, 1025-1026. The resistance against the regime coalesced not just around Charles de Gaulle in his London exile, but also formed at various levels and in different locations within France.32Albertelli, Sébastien: La lutte clandestine en France. Une histoire de la Résistance, 1940–1944. Paris 2019: Seuil, 74-76, Beaupré, Nicolas: Les grandes guerres, 1914–1945. Paris 2012: Belin, 944-961; Gildea, Robert: Fighters in the Shadows. London 2015: Faber & Faber; Waechter, Matthias: Der Mythos des Gaullismus. Heldenkult, Geschichtspolitik und Ideologie 1940 bis 1958. Göttingen 2006: Wallstein; Willms, Johannes: Der General. Charles de Gaulle und sein Jahrhundert. München 2019: Beck. A recurring argument in the deheroization and delegitimisation processes was accusing Pétain of having betrayed the French people. That act of betrayal was explained most commonly by a striking weakness of Pétain’s character, who was portrayed either as defeatist, power-hungry or decrepit. In parallel to the official adoration of Pétain in the Vichy regime, an opposing, invective discourse about the head of state emerged.33Schubert, Stefan: Reinventing Pétain: “Crisis and Cults of Personality in Vichy France, 1940–1942”. In: Baberowski, Jörg / Wagner, Martin (Eds.): Crises in Authoritarian Regimes. Fragile Orders and Contested Powers. New York 2022: Campus, 241-265. AN 3W/303. Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales. I tracts et presse clandestins. Barafort: Les mensonges qui nous ont fait tant de mal, in Libération, 4 December 1942; AN 3W/303. Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales. I tracts et presse clandestins. Le complot Pétain, in Libération 8 January 1943; AN 3W/303. Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales. I tracts et presse clandestins. Revue de la presse clandestine de France par Jean Roy, 7 September 43.

Within France, numerous underground newspapers and pamphlets accused Pétain of betraying France. Three arguments were put forward: first, he had signed the armistice by which France was not defeated, but betrayed and sold out. At the moment in which other occupied countries began resisting, he had bowed before Hitler in Montoire, the man who had had French hostages shot.34AN 3W/303 Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales (documents portant le cachet du commissariat national à l’Intérieur, Service L.T.E., Documentation). I tracts et presse clandestins. 1 Pétain et la cinquième colonne. Editions du Franc-Tireur. The second moment of betrayal related to the illegal usurpation of state authority:

“The government of a Pétain or a Laval that ignores all laws on which their authority is based is illegal. It is a usurped power. No citizen is legally or even morally obliged to subject himself to it.”35AN 2 AG 456. CC attaques gaullistes contre le Maréchal. CC XXIX A. Pamphlet gaulliste sur la légalité du gouvernement du Maréchal: “Le gouvernement d’un Pétain ou d’un Laval, qui méconnaît toutes les lois sur lesquelles est assise son autorité, est ILLEGAL. C’est un POUVOIR USURPE. Aucun citoyen n’a le devoir légal ou même moral de s’y soumettre.”

The opponents of the regime saw the third moment of betrayal in the collaboration with the German occupiers.36AN 2 AG 456. CC attaques gaullistes contre le Maréchal. Combat. Organe du mouvement de Libération Française. Copie d’un Lettre au Maréchal Pétain. May 1942. Precisely this last point took on the quality of an accusation against Pétain, namely that he had outright engaged in a conspiracy against the Third Republic, which he had been working to overthrow since the 1930s. He had supposedly achieved that goal in summer 1940:

“And the betrayal continues under the abominable dictatorship of the defeated military officers. At its head is the marshal, who orders the French to submit to the law of the victor. To follow the marshal means to accept slavery forever.”37AN 2 AG 456. CC attaques gaullistes contre le Maréchal. Le cas Pétain. September 1941: “Et la trahison continue sous la dictature odieuse des militaires vaincus. A leur tête se tient le Maréchal, il ordonne aux Français de se soumettre à la loi du vainqueur. Suivre le Maréchal, c’est accepter d’être esclave pour toujours.” A similar narrative is found in: AN 3W/303 Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales (documents portant le cachet du commissariat national à l’Intérieur, Service L.T.E., Documentation). I tracts et presse clandestins. 1 Pétain et la cinquième colonne. Editions du Franc-Tireur.

The last point conveyed a clear political message: whoever accepted the rule of the ‘traitor’ was making themselves slaves. The accusation of betrayal proves to be a powerful instrument of political and social control. Equating Pétain with the regime meant that the deheroization of the head of state could become a key political strategy for delegitimising and destabilising the État français. The accusation of treason proved to be one of the most potent weapons in the propaganda battle for the future of France during the Second World War.

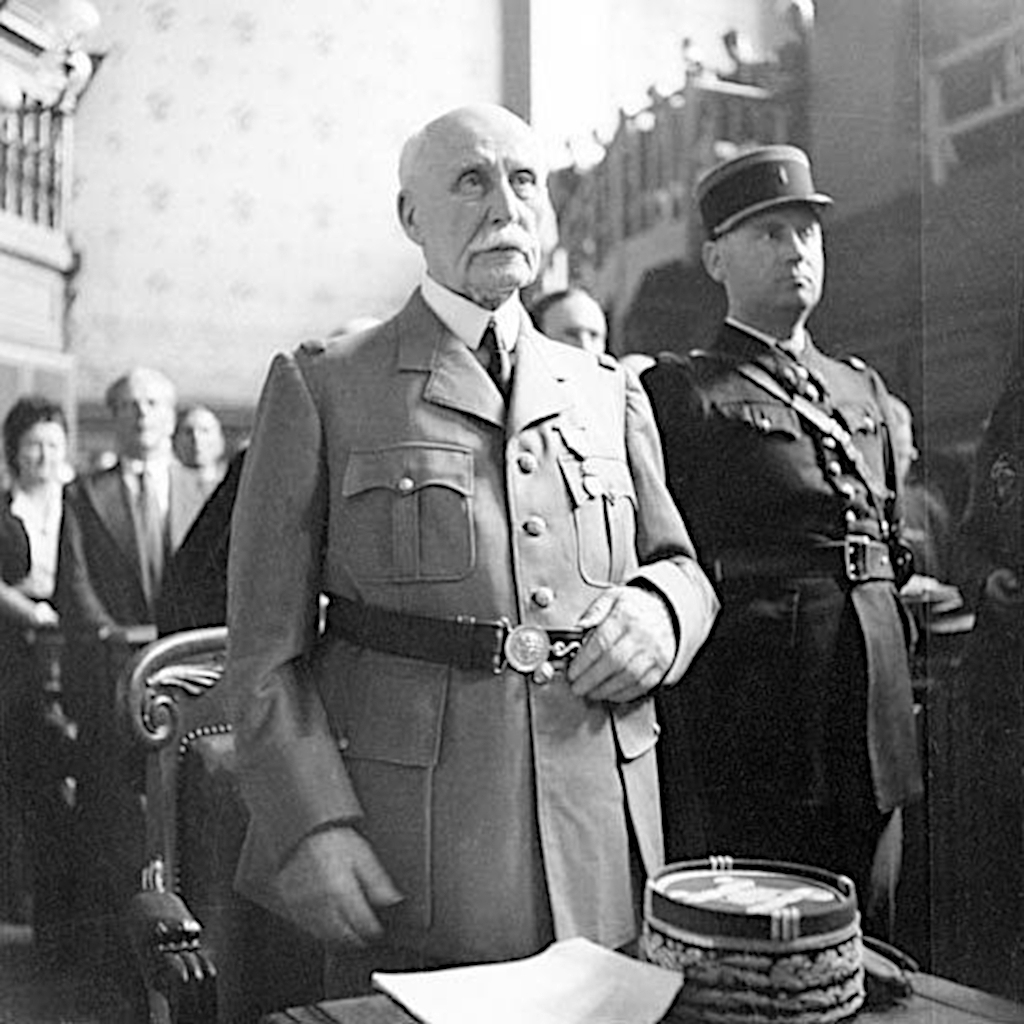

These accusations in no way disappeared after the Vichy regime ended. The unifying function that Philippe Pétain acquired as a treacherous figure after the end of the war became apparent when he was tried for high treason in July and August 1945 (fig. 2).38Procès du Maréchal Pétain: compte rendu officiel in extenso des audiences de la Haute Cour de Justice. Paris 1976; Varaut, Jean-Marc: Le procès Pétain. 1945–1995. Paris 1995. The disputes and points of conflict that had already plagued the Third Republic were concealed at the moment the traitor was identified and sentenced. In this case, Pétain’s ‘betrayal’ became a deception that was to bridge the country’s four years of internal turmoil and strengthen the social cohesion within the new Fourth Republic. With Pétain’s conviction, negative passions and internal conflicts were bundled together and personified in a prominent player, which resulted in French society failing to critically examine its own history.39Rousso, Henry: Le syndrome de Vichy. (1944 – 198…). Paris 1987; Florin, Christiane / Pétain, Philippe / Laval, Pierre: Das Bild zweier Kollaborateure im französischen Gedächtnis; ein Beitrag zur Vergangenheitsbewältigung in Frankreich von 1945 bis 1995. Frankfurt a. M. 1997.

As was made clear in the introductory remarks, trust is a constitutive element of betrayal. If a majority of a community sees a breach of that trust, it will lead to the ostracisation of the betrayer, who becomes a surface on which to project negative emotions. The example of Philippe Pétain makes clear that it is in no way obvious when such a point is reached. Had the majority of French society regarded Pétain’s actions in June 1940 as betrayal, he would not have been able to hold his position as head of state even with military force considering the weakness of the French army. Intelligence reports also testify to the marshal’s wide popularity amongst the French people through to 1944. It is not possible to know how many French considered Pétain to be a hero and how many saw him as a betrayer. In the collective memory of the French, both figures were and still are interrelated in a way that has not been entirely clarified. The reference to both the heroic and treacherous figure of Pétain still serves the purpose of negotiating the moral and political norm and value framework of French society, and in the first decades of the 21st century, it has also hardly lost any relevance for the self-discussion of French society.

6. Perspectives

This article is limited largely to one variety of treacherous conduct that is suited to shed light on the relation between betrayal and the heroic from an ideal-typical viewpoint. An approach guided by ideal types only ever constitutes an attempt that can never completely do justice to the variety of human experience. In light of this, the final part of this article critically reflects on the definition of betrayal that has been given herein using a number of archetypal figures.

There are forms of betrayal that cannot be situated in the field of the heroic. The ‘everyday’ breach of trust is antithetical to the exceptional heroic and its negations. When a pupil tells the teacher that a number of classmates were disobedient, she might be ostracised from the class for a short time and shunned as a betrayer or telltale. However, she has met the social expectation of sincerity and honesty placed on her. This example critically illuminates the assumption of transgressiveness, exceptionality and the implicit ⟶agency of the ‘betrayer’.

In addition, there are certainly also positively connoted forms of treacherous conduct. The political whistle-blower of the 21st century makes this ambivalence plain. On the one hand, he threatens national security; on the other hand, he represents core democratic and rule-of-law values. The example of the whistle-blower also demonstrates that betrayal is a constant in political communication.40Boveri, Marget: Der Verrat im 20. Jahrhundert. Vol. 1: Für und gegen die Nation. Das sichtbare Geschehen. Reinbek 1956: Rowohlt, 7; Pozzi, Enrico: “Le paradigme du traître”. In: Scarfone, Dominique (Ed.): De la trahison. Paris 1999, 1-33; Schehr, Sébastien: Traîtres et trahisons. De l’antiquité à nos jours. Paris 2008. Whether and when betrayal needs to be regarded as such, or even sanctioned, depends most of all on the interpretation of the act of betrayal.

The figure of the spy likewise eludes clear classifications in the web of interrelation between betrayal and the heroic. The spy’s unequivocal mission is to be accepted into other communities and make their knowledge accessible for the benefit of the spy’s own community. Thus, betrayal is a constitutive element of the heroized protagonist in the genre of the spy narrative. Spies are suspect even when they reveal heroic qualities. When they save human life, their country or even the world, “they nevertheless operate in secret, and in so doing are not seldom perpetrators in a negative sense”.41Barbara Korte: Spion. In: Compendium heroicum, ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher, Anna Schreurs-Morét, and Ralf von den Hoff, published by Sonderforschungsbereich 948, University of Freiburg, Freiburg 2018-02-09. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/spion.

Finally, it also bears referencing the deserter, a status which is legally defined. By committing the act of insubordination or desertion, such figures also commit treason, thereby distancing themselves from their communities as typological anti-heroes. Insubordinate figures generally cannot expect to be able to join another community, as the burden of the crime attributed to them emanates beyond their former groups. In this sense, the insubordinate individual does not mark the boundary between ‘us’ and ‘the others’, but between ‘us’ and ‘oneself’.

These and similar examples break open the dichotomy between betrayal and the heroic, and add additional facets to it. The heuristic definition of betrayal and the figure of the betrayer proposed in this article provide a set of tools with which these figures can be analytically comprehended and integrated into a broad concept of the heroic. To regard betrayal as a communicative mechanism that contributes to structuring the imaginary field of the heroic directs attention to the discursive negotiation processes and interpretational struggles through which the social norm and value framework is challenged, explained and, in some cases, constructed. Although not every treacherous figure can be located within in the imaginary field of the heroic, this concept still helps to decipher the complex web of interrelation and interdependence present in social constructions of reality, including heroization and deheroization processes.

7. Einzelnachweise

- 1Javeau, Claude: Anatomie de la trahison. Paris 2007; Schehr, Sébastian: “La trahison. Une perspective sociohistorique sur la transgression en politique”. In: Parlement[s], Revue d’histoire politique 22 (2014), 21-35; Schlink, Bernhard: “Der Verrat”. In: Schröter, Michael (Ed.): Der willkommene Verrat. Beiträge zur Denunziationsforschung. Weilerswist 2007, 1-20; Krischer, André: “Von Judas bis zum Unwort des Jahres 2016. Verrat als Deutungsmuster und seine Deutungsrahmen im Wandel”. In: Frischer, André (Ed.): Verräter. Geschichte eines Deutungsmusters. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2019, 7-44.

- 2The concept of an ‘imaginary field of the heroic’ allows for insights to be gained into the processes how extraordinary, liminal figures are constructed, and it facilitates the analysis of the underlying social power structure, cf. Gölz, Olmo: “The Imaginary Field of the Heroic. On the Contention between Heroes, Martyrs, Victims and Villains in Collective Memory”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 (2019): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories, 27-38. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/04.

- 3Bröckling, Ulrich: “Negations of the Heroic – A Typological Essay”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 (2019), 39-43. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/05.

- 4Ben-Yehuda, Nachman: Betrayals and Treason. Violations of Trust and Loyalty. London 2001; Queyrel-Bottineau, Anne: Trahison et Traîtres dans l’Antiquité: actes du colloque International. Paris 2012; Billore, Maïté: La trahison au Moyen Âge: de la monstruosité au crime politique. Rennes 2009; Tracy, Larissa: Treason: medieval and early modern adultery, betrayal, and shame. Boston / Leiden 2019; Irischer, André: Verräter: Geschichte eines Deutungsmusters. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna; Javeau, Claude / Schehr, Sebastian: La trahison. De l’adultère au crime politique. Paris 2014.

- 5Giesen, Bernhard: Zwischenlagen. Das Außerordentliche als Grund der sozialen Wirklichkeit. Weilerswist 2010.

- 6Bröckling: “Negations of the Heroic”, 2019.

- 7Krischer: “Verrat als Deutungsmuster”, 2019, 10; Schehr, Sébastien: “Sociologie de la trahison”. In: Cahiers internationaux de sociologie 123 (2007), 313-323; Schlink: “Verrat“, 2007.

- 8Javeau: “Anatomie de la trahison”, 2014; Schlink: “Verrat“, 2007.

- 9Giesen, Bernhard: Triumph and Trauma. Boulder 2004, 1-4; Gölz: “Imaginary Field”, 2019.

- 10In this sense, but of course with reverse intent, the betrayer fulfils a similar socio-cultural function to that of the martyr, who symbolises and, to an extent, defines the boundaries between two communities of faith. The concept drawn upon here was developed by Olmo Gölz, whom we would like to thank for the stimulating discussion. See Gölz, Olmo: “Martyrdom and the Struggle for Power. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Martyrdom in the Modern Middle East”. In: Behemoth. A Journal on Civilisation 12.1 (2019), 2-13.

- 11Girard, René: Der Sündenbock. Zurich 1988: Benziger; Viertmann, Christine / Schuppender, Bernd: Der Sündenbock in der öffentlichen Kommunikation. Schuldzuweisungsrituale in der Medienberichterstattung. Wiesbaden 2015: Springer, 35-88.

- 12Mock, Steven: Symbols of Defeat in the Construction of National Identity. Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, 215-223.

- 13Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero as an Effect. Boundary work in Processes of Heroization”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 (2019), 17-26, 20. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/03.

- 14Frevert, Ute: Vertrauensfragen. Eine Obsession der Moderne. München 2013: Beck; Frevelt, Ute: “Vertrauen – eine historische Spurensuche”. In: Frevelt, Ute (Ed.): Vertrauen. Historische Annäherungen. Göttingen 2003: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 7-66; Luhmann, Niklas: Vertrauen. Ein Mechanismus der Reduktion sozialer Komplexität. 4th Edition. Stuttgart 2000: Lucius und Lucius; Reemtsma, Jan Philipp: Vertrauen und Gewalt. Versuch über eine besondere Konstellation der Moderne. Hamburg 2008: Hamburger Edition.

- 15Leonhard, Jörn: Der überforderte Frieden. Versailles und die Welt 1918–1923. 2nd Edition. Munich 2019: C.H. Beck, 902-903.

- 16Leonhard: Der überforderte Frieden, 2019, 381.

- 17Clemenceau, Georges: Speech of 20 November 1917. Quoted from: Becker, Jean-Jacques: Clemenceau, l’intraitable. Paris 1998: Levi, 134-135 and Winock, Michel: Clemenceau. Paris 2007: Perrin, 426-428; Dallas, Gregor: At the Heart of a Tiger. Clemenceau and His World 1841–1929. London 1993: Carroll & Graf, 501-502.

- 18Quoted from: Janz, Oliver: 14. Der große Krieg. Frankfurt a. M. 2013: Campus, 323; Keil, Lars-Broder / Kellerhoff, Sven Felix: Deutsche Legenden. Vom “Dolchstoß” und anderen Mythen der Geschichte. Berlin 2002: Links, 36; Lobenstein-Reichmann, Anja: “Die Dolchstoßlegende. Zur Konstruktion eines sprachlichen Mythos”. In: Muttersprache 112 (2002), 25-41.

- 19Troeltsch, Ernst: “Links und Rechts (März 1919)”. In: Troeltsch, Ernst: Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Ed. by Friedrich Wilhelm Graf, Christian Albrecht and Gangolf Hübinger. Vol. 14: Spectator-Briefe und Berliner Briefe (1919–1922). Berlin 2015: de Gruyter, 72-78, 76-77.

- 20Leonhard: Der überforderte Frieden, 2019, 591.

- 21Benvindo, Bruno / Majerus, Benoît: “Belgien zwischen 1914 und 1918. Ein Labor für den totalen Krieg”. In: Bauerkämpfer, Arnd / Julien, Élise (Eds.): Durchhalten! Krieg und Gesellschaft im Vergleich 1914–1918. Göttingen 2010: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 127-148, 145-146.

- 22Rousseaux, Xavier / van Ypersele, Laurence: “Leaving the War. Popular Violence and Judicial Repression of ‘Unpatriotic’ Behaviour in Belgium (1918–1921)”. In: European Review of History / Revue européenne d’histoire 12 (2005), 3-22.

- 23Leonhard: Der überforderte Frieden, 2019, 1269.

- 24Schubert, Stefan: “The Downfall of a Hero: The Vilification of Philippe Pétain”, in: Saeculum, Special Issue: Villains! Constructing Narratives of Evil (in press).

- 25Ferro, Marc: Petain. Paris 1987: Fayard; Pedroncini, Guy: Pétain, le soldat 1914–1940. Paris 1998; Vergez-Chaignon, Bénédicte: Pétain. Paris 2014: Perrin. Partial aspects of the heroization of Pétain and his significance as a political myth are focused on by Servent, Pierre: Le mythe Pétain. Verdun, ou, les tranchées de la mémoire. Paris 1992: Payot and Fischer, Didier: Le mythe Pétain. Paris 2002: Flammarion.

- 26“La confiance du général Pétain”. In: Le Rappel, 18 March 1916.

- 27Le Petit Journal. Supplément du dimanche, 16 February 1919: “Après les événements d’avril et de mai 1917, une crise de dépression morale sévit un instant dans l’armée. Pétain s’attacha à relever les volontés abattues, à exalter les âmes. Il visita successivement près d’une centaine de divisions, écoutant les chefs, les officiers, jusqu’aux simples soldats. Et partout, sur son passage, il sut faire vibrer les cœurs et rétablir la confiance.” Ducray, Camille: Le maréchal Pétain. Paris 1919, 20: “Le sol de France est enfin délivré. Pétain a toujours eu confiance dans la valeur de ses soldats, qu’il estime et qu’il aime.” Pétain himself referred to the attribute of trust at numerous public appearances, like he did for example during a speech at the dedication of the memorial to fallen soldiers on Côte 304: “Aux premiers renforts jetés à la tête de l’ennemie et qui s’engageaient dans un combat confus, par un temps épouvantable, j’ai dit d’abord: ‘Confiance!’.” Pétain, Philippe: quoted from L’Echo de Paris, 18 June 1934.

- 28Lackerstein, Debbie: National regeneration in Vichy France. Ideas and policies, 1930–1944. Farnham 2012: Ashgate; Norton, Mason: “Counter-Revolution? Resisting Vichy and the National Revolution”. In: Dodd, Lindsey / Lees, David (Eds.): Vichy France and everyday life. Confronting the challenges of wartime, 1939–1945. London 2018, 197-211; Paxton, Robert: Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944. New York 1972: Columbia University Press.

- 29“Pour accomplir la tâche immense qui nous incombe, j’ai besoin de votre confiance. Vos représentants me l’ont donnée en votre nom.“ Speech from 11 July 1940. In: Pétain, Philippe: Discours aux Français. Paris 1989: Michel, 68.

- 30Marc-Vincent, P.: De l’armistice a la paix. La France nouvelle, Tome 1. 25 Juin–24 Octobre 1940. Paris 1940: Tallandier, 215: “Pour poursuivre avec dignité ce programme de reconstruction de l’Europe, faisons confiance au Maréchal, qui incarne la France dans ce qu’elle a de plus haut et de plus noble…”

- 31Baruch, Marc-Olivier: Vichy-Regime. Frankreich 1940–1944. Stuttgart 2000: Reclam; Cointet, Michèle: Nouvelle histoire de Vichy (1940–1945). Paris 2011: Fayard; Ferro: “Pétain”, 326-327; Winkler, Heinrich August: Die Zeit der Weltkriege. 1914–1945. 3rd edition. München 2016: Beck, 1025-1026.

- 32Albertelli, Sébastien: La lutte clandestine en France. Une histoire de la Résistance, 1940–1944. Paris 2019: Seuil, 74-76, Beaupré, Nicolas: Les grandes guerres, 1914–1945. Paris 2012: Belin, 944-961; Gildea, Robert: Fighters in the Shadows. London 2015: Faber & Faber; Waechter, Matthias: Der Mythos des Gaullismus. Heldenkult, Geschichtspolitik und Ideologie 1940 bis 1958. Göttingen 2006: Wallstein; Willms, Johannes: Der General. Charles de Gaulle und sein Jahrhundert. München 2019: Beck.

- 33Schubert, Stefan: Reinventing Pétain: “Crisis and Cults of Personality in Vichy France, 1940–1942”. In: Baberowski, Jörg / Wagner, Martin (Eds.): Crises in Authoritarian Regimes. Fragile Orders and Contested Powers. New York 2022: Campus, 241-265. AN 3W/303. Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales. I tracts et presse clandestins. Barafort: Les mensonges qui nous ont fait tant de mal, in Libération, 4 December 1942; AN 3W/303. Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales. I tracts et presse clandestins. Le complot Pétain, in Libération 8 January 1943; AN 3W/303. Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales. I tracts et presse clandestins. Revue de la presse clandestine de France par Jean Roy, 7 September 43.

- 34AN 3W/303 Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales (documents portant le cachet du commissariat national à l’Intérieur, Service L.T.E., Documentation). I tracts et presse clandestins. 1 Pétain et la cinquième colonne. Editions du Franc-Tireur.

- 35AN 2 AG 456. CC attaques gaullistes contre le Maréchal. CC XXIX A. Pamphlet gaulliste sur la légalité du gouvernement du Maréchal: “Le gouvernement d’un Pétain ou d’un Laval, qui méconnaît toutes les lois sur lesquelles est assise son autorité, est ILLEGAL. C’est un POUVOIR USURPE. Aucun citoyen n’a le devoir légal ou même moral de s’y soumettre.”

- 36AN 2 AG 456. CC attaques gaullistes contre le Maréchal. Combat. Organe du mouvement de Libération Française. Copie d’un Lettre au Maréchal Pétain. May 1942.

- 37AN 2 AG 456. CC attaques gaullistes contre le Maréchal. Le cas Pétain. September 1941: “Et la trahison continue sous la dictature odieuse des militaires vaincus. A leur tête se tient le Maréchal, il ordonne aux Français de se soumettre à la loi du vainqueur. Suivre le Maréchal, c’est accepter d’être esclave pour toujours.” A similar narrative is found in: AN 3W/303 Dossier III. Pétain. Pièces générales (documents portant le cachet du commissariat national à l’Intérieur, Service L.T.E., Documentation). I tracts et presse clandestins. 1 Pétain et la cinquième colonne. Editions du Franc-Tireur.

- 38Procès du Maréchal Pétain: compte rendu officiel in extenso des audiences de la Haute Cour de Justice. Paris 1976; Varaut, Jean-Marc: Le procès Pétain. 1945–1995. Paris 1995.

- 39Rousso, Henry: Le syndrome de Vichy. (1944 – 198…). Paris 1987; Florin, Christiane / Pétain, Philippe / Laval, Pierre: Das Bild zweier Kollaborateure im französischen Gedächtnis; ein Beitrag zur Vergangenheitsbewältigung in Frankreich von 1945 bis 1995. Frankfurt a. M. 1997.

- 40Boveri, Marget: Der Verrat im 20. Jahrhundert. Vol. 1: Für und gegen die Nation. Das sichtbare Geschehen. Reinbek 1956: Rowohlt, 7; Pozzi, Enrico: “Le paradigme du traître”. In: Scarfone, Dominique (Ed.): De la trahison. Paris 1999, 1-33; Schehr, Sébastien: Traîtres et trahisons. De l’antiquité à nos jours. Paris 2008.

- 41Barbara Korte: Spion. In: Compendium heroicum, ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher, Anna Schreurs-Morét, and Ralf von den Hoff, published by Sonderforschungsbereich 948, University of Freiburg, Freiburg 2018-02-09. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/spion.

8. Selected literature

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: Clemenceau, l’intraitable. Paris 1998: Levi.

- Ben-Yehuda, Nachman: Betrayals and Treason. Violations of Trust and Loyalty. London 2001: Perseus.

- Cointet, Michèle: Nouvelle histoire de Vichy (1940–1945). Paris 2011: Fayard.

- Dallas, Gregor: At the Heart of a Tiger. Clemenceau and His World 1841–1929. London 1993: Carroll & Graf.

- Fischer, Didier: Le mythe Pétain. Paris 2002: Flammarion.

- Florin, Christiane: Philippe Pétain und Pierre Laval. Das Bild zweier Kollaborateure im französischen Gedächtnis. Ein Beitrag zur Vergangenheitsbewältigung in Frankreich von 1945 bis 1995. Frankfurt a. M. 1997: Lang.

- Gölz, Olmo: “The Imaginary Field of the Heroic. On the Contention between Heroes, Martyrs, Victims and Villains in Collective Memory”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 (2019): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories, 27-38. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/04.

- Javeau, Claude: Anatomie de la trahison. Paris 2007: CIRCE.

- Keil, Lars-Broder / Kellerhoff, Sven Felix: Deutsche Legenden. Vom “Dolchstoß” und anderen Mythen der Geschichte. Berlin 2002: Links.

- Krischer, André: “Von Judas bis zum Unwort des Jahres 2016. Verrat als Deutungsmuster und seine Deutungsrahmen im Wandel”. In: Kirscher, André (Ed.): Verräter. Geschichte eines Deutungsmusters. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2019: Böhlau, 7-44.

- Lackerstein, Debbie: National Regeneration in Vichy France. Ideas and Policies, 1930–1944. Farnham 2012: Ashgate.

- Leonhard, Jörn: Der überforderte Frieden. Versailles und die Welt 1918–1923. 2nd Edition. Munich 2019: C.H. Beck.

- Lobenstein-Reichmann, Anja: “Die Dolchstoßlegende. Zur Konstruktion eines sprachlichen Mythos”. In: Muttersprache 112 (2002), 25-41.

- Rousso, Henry: Le syndrome de Vichy. (1944–198…). Paris 1987: Seuil.

- Schehr, Sébastian: “La trahison. Une perspective sociohistorique sur la transgression en politique”. In: Parlement[s], Revue d’histoire politique 22 (2014), 21-35.

- Schlink, Bernhard: “Der Verrat”. In: Schöner, Michael (Ed.): Der willkommene Verrat. Beiträge zur Denunziationsforschung. Weilerswist 2007: Velbrück Wissenschaft, 1-20.

- Schubert, Stefan: “Reinventing Pétain: Crisis and Cults of Personality in Vichy France, 1940–1942”. In: Baberowski, Jörg / Wagner, Martin (Eds.): Crises in Authoritarian Regimes. Fragile Orders and Contested Powers. New York 2022: Campus, 241-265.

- Schubert, Stefan: “The Downfall of a Hero: The Vilification of Philippe Pétain”, in: Saeculum, Special Issue: Villains! Constructing Narratives of Evil (in press).

- Servent, Pierre: Le mythe Pétain. Verdun, ou, les tranchées de la mémoire. Paris 1992: Payot.

- Vergez-Chaignon, Bénédicte: Pétain. Paris 2014: Perrin.

- Winock, Michel: Clemenceau. Paris 2007: Perrin.

9. List of images

- 1Philipp Scheidemann und Matthias Erzberger als Dolchstößler, Karikatur, 1924. Beschriftung: „Das bist Du! Du schuft! / Deutsch: Deutsche, denkt daran!“Quelle: User:Before_My_Ken / Wikimedia Commons; publiziert in: Gold, Helmut / Heuberger, Georg (Hg.): Abgestempelt. Judenfeindliche Postkarten. Auf der Grundlage der Sammlung Wolfgang Haney. Heidelberg 1999: Umschau/Braus, 268.Lizenz: Gemeinfrei

- 2Philippe Pétain während seines Hochverratsprozesses, Paris, 30. Juli 1945. Anonyme Fotografie.Quelle: User:Guise / Wikimedia CommonsLizenz: Gemeinfrei / Urheberrecht erloschen gemäß § 66 UrhG