- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 28. Juni 2024

Inhalt

1. Introduction

In the US, firefighters are considered the paragons of bravery. The London Fire Brigade fought for every life during the catastrophic fire in Grenfell Tower and received waves of praise because of it. After their resolute work during the Notre Dame Cathedral fire in April 2019, the Parisian Brigade des Pompiers experienced a rise in its status. The German Feuerwehr (fire service, literally: fire defence) took first place in the 2019 Public Value Atlas Germany.1HHL. Leipzig Graduate School of Management: GemeinwohlAtlas 2019. Online at: https://www.gemeinwohlatlas.de/ (accessed on 19.08.2019); Smith, Dennis: Dennis Smith’s History of Firefighting in America. 300 Years of Courage. New York 1978; Preuschoff, Olaf: “Die Helden von der Themse”. In: Feuerwehr Magazin 1 (2018), 68-78; “Notre-Dame: hommage aux pompiers, qui seront faits citoyens d’honneur de Paris”. In: Le Figaro 18 April 2019. Online at: http://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/notre-dame-hommage-aux-pompiers-qui-seront-faits-citoyens-d-honneur-de-paris-20190418 (accessed on 19.08.2019). In the entire Western world, both volunteer and professional fire brigades are held in high esteem. Given the political and economic conditions of the modern era, they are among the few ⟶heroic figures who seem to be lastingly stable, and are rarely criticised.2Cooper, Robyn: “The Fireman: Immaculate Manhood”. In: Journal of Popular Culture 28.4 (1995), 139-169. In light of the tasks they perform in the line of duty – fighting fires, rescuing people and property, offering aid and assistance – this might be seen as self-evident, but it is not: in countries in which the fire service is a poorly paid job for poorly trained and equipped personnel, this form of hero construction applies only to a limited extent. One reason for this is the fact that heroic action, on the one hand, is always a social attribution, but, on the other hand, it is strongly tied to objects, which is especially true for this group of professionals: firefighters who only arrive after hours, whose vehicles and pumps do not work properly due to deterioration and missing parts or lack of maintenance, and who cannot save lives for lack of protective equipment are perhaps still heroic personalities. However, because of the obvious system failures, this goes unseen in the popular reception. Skill-oriented volunteer systems, in contrast, are closely related to forms of syndicalism, with post-capitalist tendencies.3Hochbruck, Wolfgang: Helden in der Not. Eine Kulturgeschichte der amerikanischen Feuerwehr. Göttingen 2018: Wallstein, 93.

2. Extinguishing fires until the 18th century

The beginning of organised firefighting can be traced back to the vigiles of ancient Rome, who were generally slaves entrusted with this dangerous task. They disappeared with the invasions of the Germanic tribes. After that and up to the early modern period, most Western European cities had regimes in place that laid out – in great detail in some cases – the functions that every household was to perform in the event of a fire: in most instances providing buckets with extinguishing contents, and assistance in the bucket brigade. One of the night watch’s duties was to keep out an eye for fires; urban servants were usually the only individuals who were trained in how to fight fires. However, they were unable to prevent the frequent and devastating fires that nearly every European city experienced, some of them more than once. The development of the first hoses made from leather and of large, manually powered fire engines that required considerable effort and personnel to operate showed how necessary it was to have trained crews working together as a team.4Hazen, Margaret Hindle / Hazen, Robert M.: Keepers of the Flame. The Role of Fire in American Culture, 1775-1925. Princeton 1992: Princeton University Press. Three forces drove the development. First, there were the cities and towns, who were seeing their infrastructure damaged again and again by the massive blazes. For this reason, in France and Great Britain, fire brigades were often organised alongside the establishment of police; in some cases emerging out of the ⟶military or as an arm of the police. Second, fire insurance companies were formed, who of course must have had an interest in there being as little fire damage as possible. These companies hired and paid their own workforce or – at much less cost – sponsored volunteer fire brigades, either financially or complete with equipment and apparatuses. Third, citizens founded fire brigades, which acquired fire engines and other equipment either with the assistance of their communities or through associations and voluntarily organised fire control and protection.5Sullivan, Bill: “It Takes a Village to Put Out a Fire”. In: Making History [Colonial Williamsburg Blog, 5 April 2016].

3. Volunteer firefighting

With the transition from conscription to forms of self-organisation, the parameters of heroism changed. First in the US (starting in ca. 1730), then in Great Britain, and from ca. 1830 in the German countries, volunteer groups initially formed as mutual aid organisations. However, only a few years later, these were expanded into assistance programmes for entire towns or neighbourhoods. The humanist ideal behind this type of self-organisation simultaneously constitutes part of the foundation of republican conduct: a system that can only function if all members apply their skills collaboratively on behalf of the community, and the greatest collective mutual benefit is thereby achieved.6Thompson, Alexander M. III / Bono, Barbara A.: “Work without Wages: The Motivation for Volunteer Firefighters”. In: American Journal of Economics and Sociology 52.3 (1993), 323-343. DOI: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.1993.tb02553.x

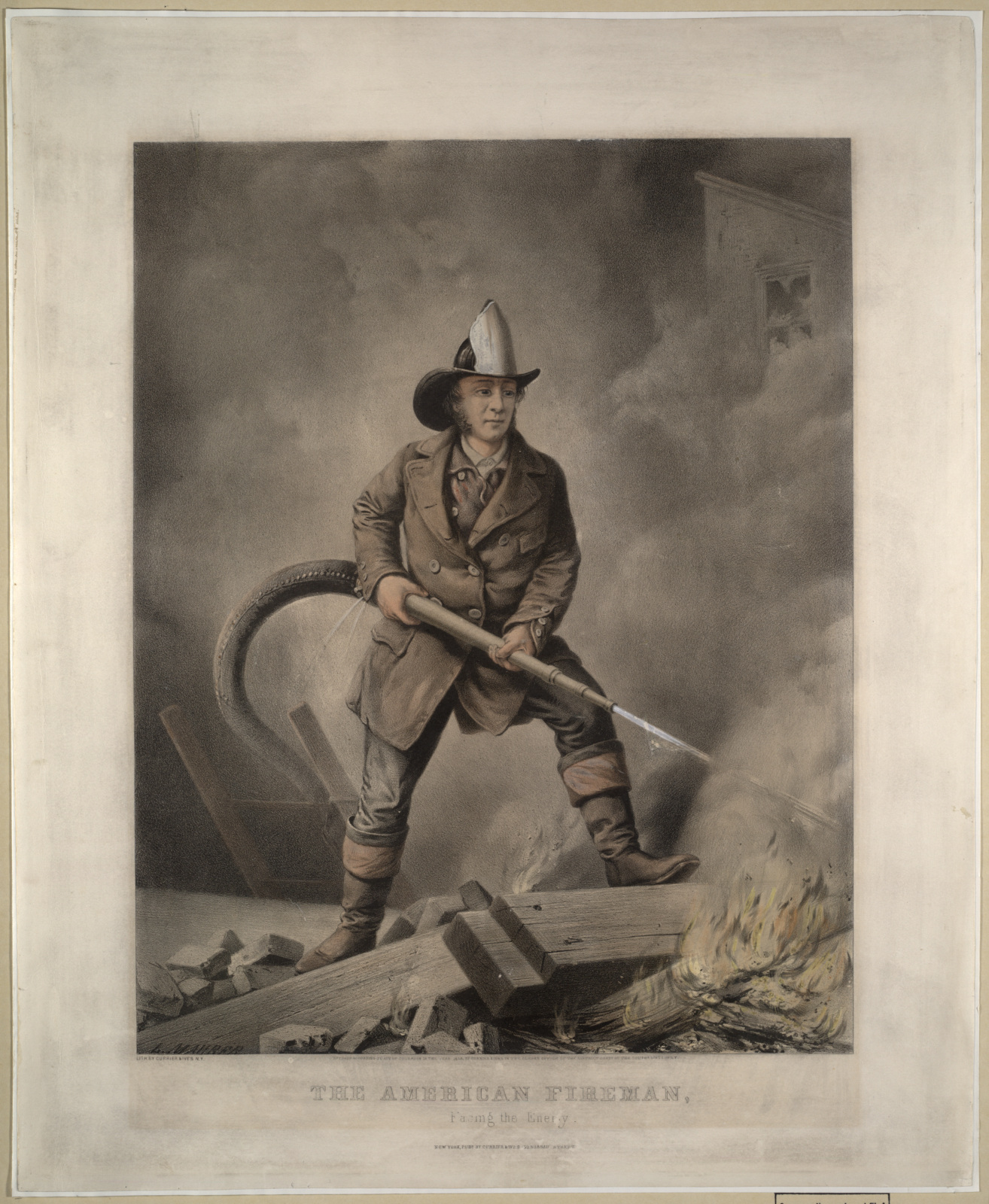

Against this background, the classic larger-than-life, boundless and often particularly powerful hero of antiquity and the Middle Ages was reduced to the courageous ordinary citizen who was – and was entirely expected to be – remunerated only by the respect and admiration from his fellow citizens. (Using ‘his’ here applies especially with regard to firefighters since it was almost entirely men who were recruited for volunteer fire companies until the later 20th century.) Furthermore, with their service, ordinary citizens often commended themselves for other public offices as well.7Hart, David K. und P. Artell Smith: “Fame, Fame-Worthiness, and the Public Service”. In: Administration & Society 20.2 (1988), 131-151. Several American presidents and other prominent politicians were members of volunteer fire departments for at least a short period of time; Benjamin Franklin is particularly well known for having been the founder of the Union Fire Company in Philadelphia in 1735.8Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 25. The fireman was linked to the classic hero topos essentially by being a role model for coming generations. In particular, the retelling of anecdotes about heroic rescues in both lithographs and anthologies projects onto that resolute effort, primarily in the US and Great Britain, an iconographic mixture of different Christian hagiologies, from the analogy to the slaying of the (fire) dragon by St. George (fig. 1) to the St. Christopher symbolism in the act of rescue, especially where the individual being rescued is a child (fig. 2).

The dominant saint in the German-speaking world is St. Florian, who is portrayed as a firefighter primarily in Catholic regions. There, the volunteer fire brigades experienced a first wave of popularity in connection with the revolutions of 1848/49 because the gymnastics (‘Turner’) clubs, many of which had participated in, or supported the revolution were put under political pressure, or banned entirely. In many places, they reorganised into fire service associations. However, this democratic background was almost entirely overshadowed by the militarisation of the volunteer associations during the decades of the German Empire (1871–1918).9Engelsing, Tobias: Im Verein mit dem Feuer. Die Sozialgeschichte der Freiwilligen Feuerwehren von 1830 bis 1950. Konstanz 1990: Faude, 56-70. Moreover, during the Third Reich, the fire service was integrated into the Nazi system of rule as Feuerschutzpolizei (‘Fire Protection Police’). In addition to fighting fires, fire brigades were then also entrusted with police functions.10Cf. Linhardt, Andreas: “Auf dem Höhepunkt der alliierten Bomberoffensiven 1944-1945”. In: Biegel, Gerd (Ed.): Kampf gegen Feuer. Zur Geschichte der Berufsfeuerwehr. Braunschweig 2000: BLM, 302-315; Blazek, Matthias: Unter dem Hakenkreuz. Die deutschen Feuerwehren 1933-1945. Stuttgart 2009: ibidem. However, German firefighters – who in the last years of World War II were often a mixture of older men, prisoners of war, forced labourers, women, and Hitlerjugend members – did objectively show great courage and heroism during Allied night-time bombing raids. After the war, the reaction in the West German zones of occupation was to strictly separate the police and the fire service. In contrast, in the German Democratic Republic, fire brigades remained a part of the police system until 1990.

4. Professionalisation

Although volunteer organisations are considerably cheaper to pay and maintain than professional fire brigades, an influential lobby of business owners managed to arrange the professionalisation of firefighting in the large cities of the US around the middle of the 19th century, using as a pretext the fact that some volunteer companies had allegedly mutated into hardly controllable bands of young men, many of which had also come under the influence of political parties. William ‘Boss’ Tweed, who practically embodied the systemic corruption in the city of New York in the mid-19th century, began his career as an officer of a volunteer company, later propping himself up on the political and sometimes violent support of his people.11Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 34. The reciprocal sabotage, and brawls between members of different companies when they arrived at fires, became legendary.

The transition to a professional occupation that took place between 1840 and 1865 in all major American cities meant municipal control and management, the establishment of uniform training regimes, a boost in technology and subsequently greater reliability. Factory owners and business people no longer had to anticipate that the volunteer fire fighters among their employees and labourers would suddenly leave for a fire. Profits were secured, while the costs of professionalising firefighting were passed on to the general public.12Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 36. The heroic image of the volunteer was consequently modified and supplemented in the transition to the professional system, to the effect that the technical equipment of most urban fire departments, with their new, horse-drawn steam-powered fire engines in lieu of the hand-drawn and manually powered fire engines, turned firefighters into heroes of the new, technical age in addition to embodying the heroic notion of those who rescue people from fire. With only some veterans joining from the discredited volunteer units, the first generation of professional firemen consisted primarily of poorly regarded and even more poorly paid immigrants, often from Ireland; thereby laying the foundation for the strongly Irish-inspired traditions of firefighting especially in the big American cities. Poor payment was compensated by a sacrifice myth established in cultural discourse, informed by Christian elements and linking firefighters’ frequent ⟶deaths on the job with heroism. This motif was also disseminated in pictorial representations, popular poetry, and on the melodrama stage. It became an integral part of American firefighters’ self-image: more than in other countries, American firefighters seem willing to take life-threatening risks, even though this has not improved their success rate – on the contrary: an estimated sixty of the 343 New York firemen who died when the World Trade Center collapsed were actually off-duty; they and others could have survived if the chain of command had been observed.13In fact, 341 active firefighters and two paramedics were killed at Ground Zero. Another three retired firefighters died who had joined those on active duty. And roughly a dozen members of volunteer fire departments are counted among the civilian victims who were either at the World Trade Center or who had rushed there to provide assistance, see Glenn Winuk: “Volunteer firefighter’s family to get 9/11 benefit”. In: NBC News, 15 January 2008. Online at: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/22671276/ns/us_news-life/t/volunteer-firefighters-family-get-benefit/#.XVp8vugzaUk (accessed on 19.08.2019). However, the FDNY has always enjoyed the reputation of not being strictly compliant with the rules and systems of command and obedience.14Kaprow, Miriam Lee: “The Last, Best Work: Firefighters in the Fire Department of New York”. In: Anthropology of Work Review 19.2 (1998), 5-26. Long before 11 September 2001, the FDNY had a heroic image. After the attacks, they attained extra ⟶martyr status. This, however, has not improved the threat environment: many who came into contact with toxic dust during rescue and recovery efforts in the ruins of the WTC are immortalised in heroifying images as they are dying from the aftereffects.

The popularity that professional firefighters enjoy is great enough that more and more women and members of minorities have been moving into this profession since circa 1970 – in some cases against considerable resistance and maltreatment and, in the beginning, only after enforcement with judicial support. Nevertheless, professional and volunteer fire departments are still largely a domain of the white lower middle-class male.15Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 57.

5. New requirements and forms of organisation

Today, the work firefighters do is changing due to extensive fire protection measures and safety installations, social factors such as professional mobility and demographic change, and environmental influences like the unmistakable effects of an uncontrolled climate crisis. The opportunities for obvious ⟶heroic acts are disappearing at the rate the number of fires continuously declines thanks to structural fire safety, personal safety measures and fire safety education starting from kindergarten and schools. In places where emergency medical services are provided by other organisations, on average, more than 60 per cent of fire brigade operations is now no longer battling actual fires, but providing technical assistance. Even more striking, in places where fire departments are also tasked with emergency medical services, they often account for 70 to 80 per cent of their operations.16Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 8. Neither the heroic act of rescuing people out of burning buildings, nor its trivialised variant of rescuing a cat from a tree, is part of the everyday experience of volunteer fire departments. However, there is also a growing disconnect between the everyday experience of professional firefighters and popular myth. Still, there are tendencies towards German firefighters being heroized in advertisements and, to an extent, in news reporting, using images that borrow considerably from American ones. The adoption of international regulations concerning equipment standards, and occupational health legislation, is at least partially responsible for this convergence; so is the range of American images, notably those originating with the Fire Department of New York, as role models. For decades after World War II, German uniforms and emblems continued to resemble patterns already in use during the Third Reich. Decreasing acceptability especially among younger people accelerated changes after the turn of the century.

6. Fighting wildfires

Fighting wildfires presents an immense physical challenge for firefighters. Their frequency and size has been increasing in Central and Western Europe due to conditions created by the climate crisis, without having yet reached the dimensions they have as seasonal phenomena in Southern Europe, North America, Russia and Australia where their size, duration and intensity, has reached catastrophic proportions.17Goldammer, Johann: “Eastern Fires, Western Smoke”. In: Wildfire Magazine 26.1 (2017), 18-25. The training, equipment, and operational readiness, of the units fighting these fires differ massively. In Russia, where fighting fires is a responsibility of the military, large wildfires have gone out of control again and again for years without any particular attention being paid to them until very recently. In the past, blazes across the globe were eventually extinguished by the regularly occurring rainfall. Due to the global climate crisis, however, this rainfall fails to materialise more and more often, and woodlands essential for the extraction of CO2 from the atmosphere go up in smoke.

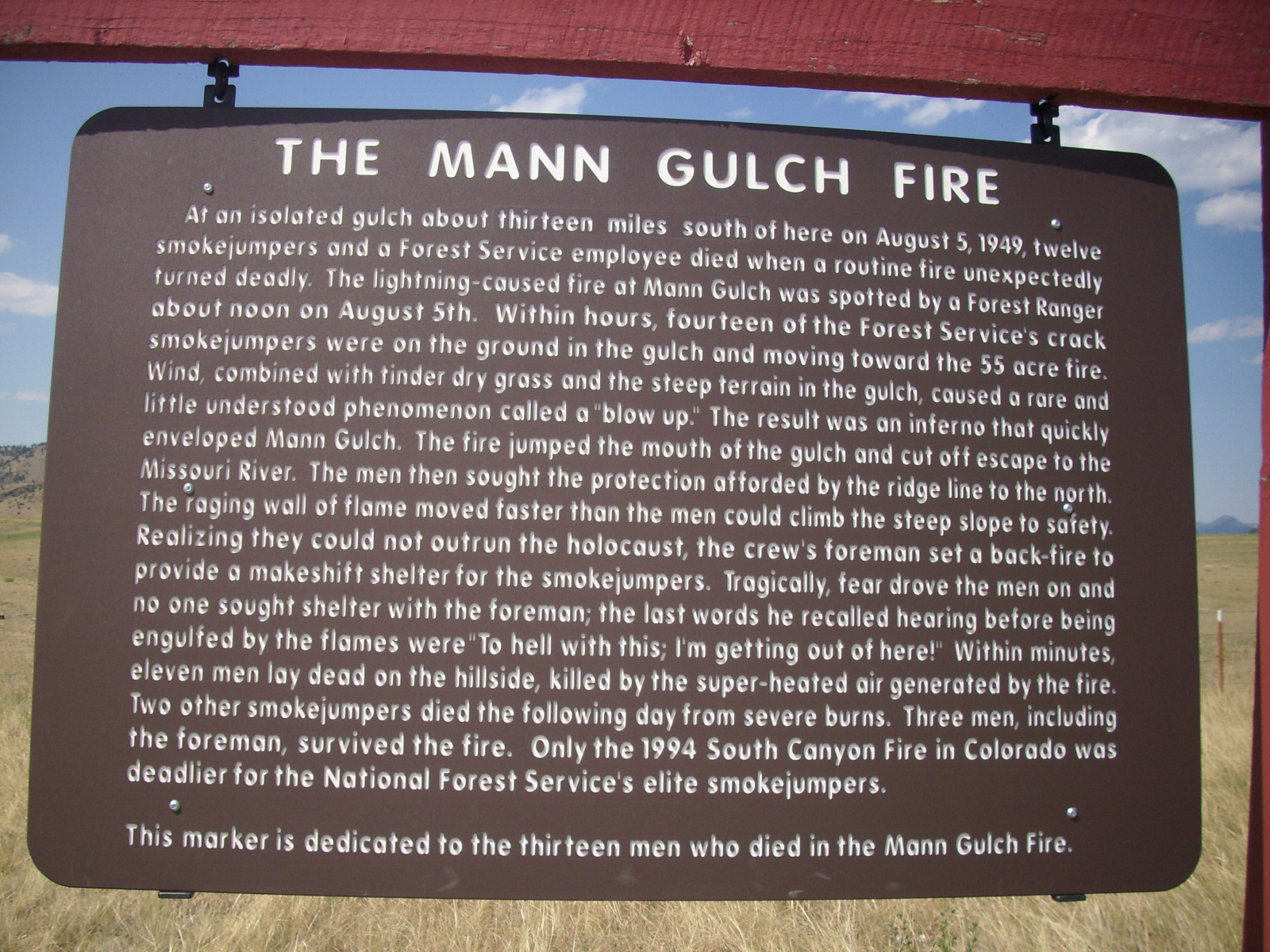

For regular fire brigades, the wildfire is a time-consuming and exhausting additional duty. In Australia and North America, firefighters are for their wildfire operations equipped with light-weight protective clothing and tools designed for the task such as hydration backpacks, ‘Pulaskis’ (an axe and hoe combination), ‘McLeod’ rakes, and ‘Gorgui’ combination tools. The highest esteem and hero status is enjoyed by the specialists of the ‘hotshot crews’, who either professionally or part-time attempt to bring forest and bushfires under control. The percentage of women among these crews, interestingly enough, is higher at almost 10 per cent than the roughly 5 per cent average among American fire departments. The glorification of deadly incidents is similar to ⟶heroic narratives about ‘normal’ firefighters , as can be seen in Norman Maclean’s work of non-fiction Young Men and Fire (1992) about the 1949 Mann Gulch Fire, where 13 members of a team of smokejumpers perished (fig. 3) or the film Only the Brave (2018, Joseph Kosinski) about the Granite Mountain Hotshots killed in the Yarnell Fire in 2013.18For more general information on the subject, see Desmond, Matthew: On the Fireline. Living and Dying with Wildland Firefighters. Chicago 2007: Chicago University Press.

7. Einzelnachweise

- 1HHL. Leipzig Graduate School of Management: GemeinwohlAtlas 2019. Online at: https://www.gemeinwohlatlas.de/ (accessed on 19.08.2019); Smith, Dennis: Dennis Smith’s History of Firefighting in America. 300 Years of Courage. New York 1978; Preuschoff, Olaf: “Die Helden von der Themse”. In: Feuerwehr Magazin 1 (2018), 68-78; “Notre-Dame: hommage aux pompiers, qui seront faits citoyens d’honneur de Paris”. In: Le Figaro 18 April 2019. Online at: http://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/notre-dame-hommage-aux-pompiers-qui-seront-faits-citoyens-d-honneur-de-paris-20190418 (accessed on 19.08.2019).

- 2Cooper, Robyn: “The Fireman: Immaculate Manhood”. In: Journal of Popular Culture 28.4 (1995), 139-169.

- 3Hochbruck, Wolfgang: Helden in der Not. Eine Kulturgeschichte der amerikanischen Feuerwehr. Göttingen 2018: Wallstein, 93.

- 4Hazen, Margaret Hindle / Hazen, Robert M.: Keepers of the Flame. The Role of Fire in American Culture, 1775-1925. Princeton 1992: Princeton University Press.

- 5Sullivan, Bill: “It Takes a Village to Put Out a Fire”. In: Making History [Colonial Williamsburg Blog, 5 April 2016].

- 6Thompson, Alexander M. III / Bono, Barbara A.: “Work without Wages: The Motivation for Volunteer Firefighters”. In: American Journal of Economics and Sociology 52.3 (1993), 323-343. DOI: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.1993.tb02553.x

- 7Hart, David K. und P. Artell Smith: “Fame, Fame-Worthiness, and the Public Service”. In: Administration & Society 20.2 (1988), 131-151.

- 8

- 9Engelsing, Tobias: Im Verein mit dem Feuer. Die Sozialgeschichte der Freiwilligen Feuerwehren von 1830 bis 1950. Konstanz 1990: Faude, 56-70.

- 10Cf. Linhardt, Andreas: “Auf dem Höhepunkt der alliierten Bomberoffensiven 1944-1945”. In: Biegel, Gerd (Ed.): Kampf gegen Feuer. Zur Geschichte der Berufsfeuerwehr. Braunschweig 2000: BLM, 302-315; Blazek, Matthias: Unter dem Hakenkreuz. Die deutschen Feuerwehren 1933-1945. Stuttgart 2009: ibidem.

- 11Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 34.

- 12Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 36.

- 13In fact, 341 active firefighters and two paramedics were killed at Ground Zero. Another three retired firefighters died who had joined those on active duty. And roughly a dozen members of volunteer fire departments are counted among the civilian victims who were either at the World Trade Center or who had rushed there to provide assistance, see Glenn Winuk: “Volunteer firefighter’s family to get 9/11 benefit”. In: NBC News, 15 January 2008. Online at: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/22671276/ns/us_news-life/t/volunteer-firefighters-family-get-benefit/#.XVp8vugzaUk (accessed on 19.08.2019).

- 14Kaprow, Miriam Lee: “The Last, Best Work: Firefighters in the Fire Department of New York”. In: Anthropology of Work Review 19.2 (1998), 5-26.

- 15Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 57.

- 16Hochbruck: Helfer in der Not, 2018, 8.

- 17Goldammer, Johann: “Eastern Fires, Western Smoke”. In: Wildfire Magazine 26.1 (2017), 18-25.

- 18For more general information on the subject, see Desmond, Matthew: On the Fireline. Living and Dying with Wildland Firefighters. Chicago 2007: Chicago University Press.

8. Selected literature

- Crawford Sr., Robert J. / Crawford, Delores A.: Black Fire. Portrait of a Black Memphis Firefighter. Charleston, SC, 2003: The History Press.

- Greenberg, Amy S.: Cause for Alarm. The Volunteer Fire Department in the Nineteenth-Century City. Princeton 1998: Princeton University Press.

- Hazen, Margaret Hindle / Hazen, Robert M.: Keepers of the Flame. The Role of Fire in American Culture, 1775–1925. Princeton 1992: Princeton University Press.

- Hensler, Bruce: Crucible of Fire. Nineteenth-Century Urban Fires and the Making of the Modern Fire Service. Washington, D.C. 2011: Smithsonian.

- Hochbruck, Wolfgang: “Volunteers and Professionals: Everyday Heroism and the Fire Service in Nineteenth-Century America”. In: Wendt, Simon (Ed.): Extraordinary Ordinariness. Everyday Heroism in the United States, Germany, and Britain, 1800–2015. Frankfurt a. M. 2016: Campus, 109-138.

- Jacobs, Alan H.: “Volunteer Fireman: Altruism in Action”. In: Arens, W. / Montague, Susan P. (Eds.): The American Dimension. Cultural Myths and Social Realities. New York 1976: Alfred Publishing, 195-205.

- Perkins, Kenneth B. / Benoit, John: The Future of Volunteer Fire and Rescue Services: Taming the Dragons of Change. Stillwater, OK, 1996: Fire Protection Publications, Oklahoma State University.

- Pyne Stephen J.: Fire in America. A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire. Princeton 1982: Princeton University Press.

- Simpson, Charles: “A Fraternity of Danger: Volunteer Fire Companies and the Contradictions of Modernization”. In: The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 55.1 (1996), 17-34.

- Thompson, Alexander M. / Bono, Barbara A: Work Without Wages: The Motivation for Volunteer Firefighters. In: American Journal of Economics and Sociology 52.3 (1993), 323-343.

9. List of images

- 1Currier & Ives: „Facing the Enemy“, 1858, nachgefärbte Lithographie, 16 x 20 Zoll, aus der Serie „American Fireman“.Quelle: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Inv.-Nr. ppmsca 01579; publiziert in: Currier & Ives: A catalogue raisonné. Hg. von Gale Research. Detroit, MI 1983: Gale Research, Nr. 0166.Lizenz: Gemeinfrei

- 2Volunteer Firemen Monument, Austin, TX., 1896, Entwurf von J. Segesman.Quelle: User:Daderot / Wikimedia Commons

- 3„The Mann Gulch Fire“, Historischer Markierungspunkt am Oberen Missouri, USA.Quelle: Fotografie von Wolfgang HochbruckLizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0