- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 28. Juni 2024

Inhalt

- 1. General remarks

- 1.1. Prerequisite conditions

- 1.2. Genesis

- 1.3. Possible interpretations

- 2. Case analysis – La Tombe du Soldat inconnu (France)

- 2.1. Genesis

- 2.2. Typology

- 2.3. Literature as a medium of memory – two examples

- 3. Conclusion: function and function transformation

- 4. Einzelnachweise

- 5. Selected literature

- 6. List of images

- Citation

1. General remarks

As the epitome of commitment and willingness to make sacrifices, the allegorical figure of the Unknown Soldier became the focal point of national memory in the period between the World Wars. The figure represented an idealised, collective and heroic imagining of the ordinary soldier who had lost his life for his fatherland. The figure of the Unknown Soldier contributed to the perpetuation of a certain type of soldier ⟶hero in the modern era and simultaneously served both the coalescence of national mourning and the retrospective legitimisation of the sacrifices made during the First World War.

1.1. Prerequisite conditions

The modern political funerary cult, in which the cult surrounding the Unknown Soldier is to be subsumed, is closely linked to processes of political, social, and cultural transformation in the 19th century, such as nation-building, militarisation or democratisation.1Cf. Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink; Prost, Antoine: “Les monuments aux morts. Culte républicain? Culte civique? Culte patriotique?” In: Ageron, Charles R. / Nora, Pierre (Eds.): Les lieux de mémoire. I. La République. Paris 1984: Gallimard, 195-228; Sivan, Emmanuel / Winter, Jay M. (Eds.): War and remembrance in the twentieth century. Cambridge 1999: Cambridge University Press. Most of all, the mobilisation of men through the gradual introduction of conscription during the 19th century resulted in the necessity to express society’s acknowledgement to fallen ⟶soldiers – who died as citizens for the nation.2Cf. Chickering, Roger: “War, society, and culture, 1850–1914: the rise of militarism”. In: Chickering, Roger / Showalter, Dennis / Ven, Hans van de (Eds.): The Cambridge History of War: War and the Modern World. Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, 124f.; Hervé Drévillon: L’individu et la Guerre. Du chevalier Bayard au Soldat inconnu. Paris 2013: Seuil, 215f. his acknowledgement was expressed through public memorialisation, which was staged through public remembrance rituals and other forms. The cult of the fallen thus over the course of the 19th century evolved into one of the important aspects of providing the populace national orientation through politically charged symbols, and it informed the novel ⟶heroization of ordinary soldiers.3Cf. Schilling, René: “Kriegshelden”. Deutungsmuster heroischer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1813–1945. Paderborn 2002: Schöningh; Wulff, Aiko: “‘Mit dieser Fahne in der Hand’. Materielle Kultur und Heldenverehrung 1871–1945”. In: Historical Social Research 34.4 (2009), 343-355; Voss, Dietmar: „Heldenkonstruktionen. Zur modernen Entwicklungstypologie des Heroischen“. In: KulturPoetik/Journal for Cultural Poetics 11 (2011), 181-202. The interpretation and ritual adoration of the soldier’s ⟶death as the sacrifice for the political community, in whose posterity and memory the fallen lived on, was the most incisive expression of the glorification of the nation, a process that was taking on religious qualities.

1.2. Genesis

The First World War represented a profound caesura in the political funerary cult.4Cf. Ackermann, Volker: “‘Ceux qui sont pieusement morts pour la France…’ Die Identität des unbekannten Soldaten”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 281-314; Laura Wittman: The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Modern Mourning, and the Reinvention of the mystical body. Toronto 2011: Toronto University Press. The number of fallen soldiers is estimated to be around nine million. The number of no longer identifiable dead who needed to be buried in mass graves exceeded the number of those who could still be allotted their own grave. Accordingly, there often was no possibility of an individual grave, and mourning rituals required adaptation to those new circumstances.5Cf. Becker, Annette: Les Monuments aux morts. Mémoire de la Grande Guerre. Paris 1991: Errance. Mourning the fallen was one of the greatest challenges facing post-war societies.6Cf. Prost, Antoine: “Le poids de la mort”. In: Cochet, François / Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (Eds.): Les soldats inconnus de la Grande Guerre. La mort, le deuil, la mémoire. Saint-Cloud 2012: Soteca, 19-42; Contamine, Philippe: „Mourir pour la patrie“. In: Babelon, Jean-Pierre / Nora, Pierre (Eds.): Les lieux de mémoire. II. La Nation. Paris 1986: Gallimard, 11-43. Manifestations of the symbolic treatment of those challenges included war monuments and cemeteries, memorials, and the cult surrounding the figure of the Unknown Soldier.7Cf. Gilzmer, Mechtild: “‘A nos morts.’ Wandlungen im Totenkult vom 19. Jahrhundert bis heute”. In: Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred (Eds.): Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich. Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung. Munich 2013: Oldenbourg, 175-198; Goebel, Stefan: “Brüchige Kontinuität. Kriegerdenkmäler und Kriegsgedenken im 20. Jahrhundert”. In: Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred (Eds.): Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich. Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung. Munich 2013: Oldenbourg, 199-224; Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred: “Heroisierung und Opferstilisierung. Grundelemente des Gefallenengedenkens von 1813 bis heute”. In: Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred (Eds.): Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich. Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung. Munich 2013: Oldenbourg, 123-158.

1.3. Possible interpretations

Proceeding from the assumption that collective identity is based on symbolic representation and dependent on the imagination of a shared past – i.e. on collective memory8Cf. Assmann, Jan: Das kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. Munich 72013: Beck, 138-140. – five typological approaches can explain the emergence of the cultural phenomenon of the Unknown Soldier:

a. The figure of the Unknown Soldier presented a response to the inadequate funerary and remembrance rituals from the time before the War. Individual burial of the dead was impracticable because of the sheer number of the fallen, which rendered traditional rituals such as familial cortèges or wakes hardly feasible. The cult surrounding the Unknown Soldier constituted one possibility of dealing with the individual loss through a kind of collective coping with the mourning.9Cf. Assmann, Jan: “Die Lebenden und die Toten”. In: Assmann, Jan (Ed.): Der Abschied von den Toten. Trauerrituale im Kulturvergleich. Göttingen 22007: Wallstein, 16-36.

b. The Unknown Soldier could contribute to the formation of a collective identity by an imagined community in which all survivors were united through the shared experience of mourning.10Cf. Winter, Jay M.: “Forms of kinship and remembrance in the aftermath of the Great War”. In: Sivan, Emmanuel / Winter, Jay M. (Eds.): War and remembrance in the twentieth century. Cambridge 1999: Cambridge University Press, 40-60; Beaupré, Nicolas: Das Trauma des Großen Krieges 1918–1932/33. Darmstadt 2009: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft; Becker, Annette: “Der Kult der Erinnerung nach dem Großen Krieg. Kriegerdenkmäler in Frankreich”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 315-324.

c. The Unknown Soldier led to the establishment of manifest places for coping with mourning, such as the Douamont Ossuary or the grave under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. The uncertainty over the unidentifiable fallen was to be compensated through the collective recognition of the deeds and achievements of the lost, and later even all, soldiers. The risk of forgetting the individual was thereby counteracted, while simultaneously creating a symbolic point of reference for processing sorrow.11Cf. Becker: “Der Kult der Erinnerung nach dem großen Krieg”, 1994, 315-324; Janz, Oliver: Das symbolische Kapital der Trauer. Nation, Religion und Familie im italienischen Gefallenenkult des Ersten Weltkriegs. Tübingen 2009: Niemeyer, 2-11; Inglis, Ken: “Entombing Unknown Soldiers: From London and Paris to Baghdad”. In: History and Memory 5.2 (1993), 7-31; Ziemann, Benjamin: “Die deutsche Nation und ihr zentraler Erinnerungsort: Das ‘Nationaldenkmal für die Gefallenen im Weltkriege’ und die Idee des ‘Unbekannten Soldaten’ 1914–1935”. In: Berding, Helmut (Ed.): Krieg und Erinnerung. Fallstudien zum 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Göttingen 2000: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 67-92.

d. As part of the political funerary cult after war’s end, the Unknown Soldier stood not just for all the fallen, but also for all those who fought. He was therefore portrayed as a unifying political figure through which social and political fissures were to be bridged. Appeals were often directed at the community at war in the name of the fallen, such as they were idealised in the codes of the ‘Union sacrée’, the ‘Geist von 1914’ (the spirit of 1914) or the ‘spirit of the trenches’ even after the war.12Cf. Wardhaugh, Jessica: “Fighting for the Unknown Soldier: The Contested Territory of the French Nation in 1934–1938”. In: Modern & Contemporary France 15 (2007), 185-201; Correia, Sílvia: “Death and Politics: The Unknown Warrior at the Center of the Political Memory of the First World War in Portugal”. In: E-Journal of Portuguese History 11 (2013), 6-29.

e. The first four possible interpretations may also apply to other forms of remembering the dead; however, in the figure of the Unknown Soldier they did achieve a greater relevance for large parts of the post-war societies. The unique aspect about the Unknown Soldier, as well as the novelty he entailed, was the individualised, figural representation of the entirety of the soldiers in which the boundaries between singular and ⟶collective heroism were dissolved.

2. Case analysis – La Tombe du Soldat inconnu (France)

Tombs of the Unknown Soldier were erected after the end of the First World War in nearly all the countries that participated. France and Great Britain were trendsetters, inaugurating their respective tombs of the Unknown Soldier (in Britain “The Unknown Warrior”) on 11 November 1920. The United States, Italy and Portugal (1921), Belgium and Czechoslovakia (1922), Bulgaria and Romania (1923) and Poland (1925) quickly followed suit. Even up to the present day, tombs of the Unknown Soldier have been installed in honour of the fallen of (not just) the First World War, such as in Australia (1993) and Canada (2000). In this article, we will limit our study to the first tombs in Paris and London, which undoubtedly functioned as models for the subsequent memorials and still today have meaningful significance in national memory. The emphasis will be placed on the French Unknown Soldier.

2.1. Genesis

The idea of the Unknown Soldier traces its origins back to a speech given by François Simon in 1916. The president of the association Souvenir français proposed exhuming the remains of an unidentifiable soldier and burying him in the Panthéon. He was to be recognised as representing the fighting men. The later minister of the interior Maurice Manoury seized on the idea: on 19 November 1918, together with Paul Morel and Georges Leredu, he submitteda law proposal in the Chamber of Deputies that aimed to have a monument erected in the Panthéon in honour of French soldiers. Subsequently, the Chamber of Deputies continually debated the identity of that nameless corpse and where to bury it, without the arguments bringing about any resolution. It was not until the news that another Unknown Soldier was to be exhumed and laid to rest in Westminster Abbey that the debate was accelerated and finally concluded; the British were not to beat them to erecting their memorial first. The national press, led by L’Intransigeant, L’Action française, and Le Journal, started a campaign to inter an Unknown Soldier beneath the Arc de Triomphe and put pressure on the government, which in turn reached a compromise on 8 November 1920 and satisfied the demands.

The exhumation took place a mere two days later. In the casemate of the citadel of Verdun, Auguste Thin, a young infantryman who had enlisted voluntarily in January 1918 and fought in the 132nd infantry regiment Verdun-Reims, selected the Unknown Soldier in the presence of veterans, war invalids, widows and orphans. His casket, adorned with flowers and decorated with the Cross of the Légion d’honneur, the Croix de guerre and the Médaille militaire (see ⟶Orders and Decorations), was transported that night to Paris, where one day later, on 11 November, the dual ceremony was to take place in celebration of both the armistice and the victory, as well as the 50th anniversary of the Third Republic. To the sounds of the Marche héroïque, the Chant du départ and La Marseillaise, the Unknown Soldier was escorted by a procession of cavalrymen from the Franco-Prussian War, soldiers and veterans, as well as young women from Alsace-Lorraine, first to the Panthéon and then, together with the heart of Léon Gambetta, to the Arc de Triomphe. While Poincaré, Joffre, Foch, and Pétain awaited the Unknown Soldier at the Panthéon, high-ranking members of the government joined the ceremony at the Arc de Triomphe. Generally speaking, the event had a largely military character compared to the very similar, yet religiously marked celebration in England.13Cf. Ackermann, Volker: “‘Ceux qui sont pieusement morts pour la France…’. Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 281-314, 284. Because the event was organised so quickly, the Unknown Soldier had to be laid on a bier in a provisional chapel of mourning until he could be buried beneath a slab on 28 January 1921.14A detailed description of the genesis of the idea of the Unknown Soldier and the selection of the corpse and its burial can be found in Jagielski, Jean-François: Le Soldat inconnu. Invention et postérité d’un symbole. Paris 2005: Imago, 51-124; und Ackermann, “Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”, 1994.

At the initiative of veterans’ associations who lamented a gradual forgetting of the fallen within society, the Flame of Memory (Flamme du Souvenir) was lit for the first time on 11 November 1923. As a visible symbol that the Unknown Soldier can never vanish from collective memory, the flame is to never extinguish. Not least those efforts of the veterans’ associations, which as former combatants also saw themselves in the Unknown Soldier, contributed to the Unknown Soldier no longer representing just the lost, but also the fallen and ultimately all soldiers. The ceremony to rekindle the flame (Ravivage de la flamme) still takes place today every evening according to the rules instituted at the time of its inception. In this sense, the cult surrounding the Unknown Soldier is still considerably relevant in France’s national remembrance practice 100 years after the end of the war, even though a gradual desacralisation of the grave can be observed: the majority of visitors are travellers who come to the site as a tourist attraction in Paris and for whom the homage to the sacrifice no longer holds significance.15In this respect, cf. Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 171f.

2.2. Typology

In his typology of memorialising heroes, Bernhard Giesen distinguishes between three modes of remembrance that he calls “rituals of remembrance”: ‘place’, sites in the biography of the hero, like his grave; ‘face’, his visual portrayal, such as in monuments, and ‘voice’, the ⟶narratives about him.16Cf. Giesen, Bernhard: Triumph and Trauma. Boulder/London 2004: Paradigm, 25-36. However, while Giesen posits that only one of these rituals can be assigned to an object of remembrance in any given case, all three modes are applied in the case of the Unknown Soldier.

As explained above, the heated debates that took place in the Chamber of Deputies over where to place the memorial ultimately resulted in the question of what the Unknown Soldier was to symbolise. The alternatives Arc de Triomphe and Panthéon can be translated into the principles of military spirit, warriorhood and armed service on the one hand and nation, republic and citizenship on the other. It was feared that under the Arc de Triomphe only the army would be honoured, evoking the previously overcome division of military and civil society; by contrast, the Panthéon could stand for the entire ‘nation at arms’.17Cf. Ackermann: “Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”, 1994, 291-296, esp. 295f. By selecting the Arc de Triomphe, the Unknown Soldier was added to the ranks of the national (war) heroes, rather than being polaced among the ⟶‘great men’ commemorated in the Panthéon. He was no ‘great man’ to be sure, but a symbol of the innumerable soldiers who had given their lives for their fatherland.18In the words of deputy Charles Dumont, quoted according to Jagielsi: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 74: “[L]e poilu que nous allons glorifier n’est pas un de ces grands hommes. Il est le symbole de la foule immense des soldats qui se sont sacrifiés pour la Patrie.” (“The poilu we will be honouring is not one of these great men. He is the symbol of the immense number of soldiers who sacrificed themselves for the fatherland.”) The hero concept was democratised. In Great Britain on the other hand, an opposing movement can be recognised, for the ‘Unknown Warrior’ was elevated to the rank of ‘great men’ with his burial in Westminster Abbey. A further argument put forward against the Panthéon related to its lack of a unifying function conveying a sense of community. As a result of the post-Revolutionary political and religious conflicts concerning the Panthéon, in the eyes of many it had become a “site of rupture” that could not engender any consensus in society.19Cf. Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 73. Moreover, due to Zola’s interment there, who was condemned as a traitor to his country for his involvement in the Dreyfus affair especially by conservatives, the Panthéon had been denationalised and could no longer serve as a national place of remembrance.20Cf. Inglis: “Grabmäler für unbekannte Soldaten”, 1993, 157, as well as La Naour, Jean-Yves: “Le soldat inconnu: Une histoire polémique”. In: Cochet, François / Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (Eds.): Les Soldats inconnus de la Grande Guerre: la mort, le deuil, la mémoire. Saint-Cloud 2012: Soteca, 307-321, 316f.

There were also various phrasings considered for the inscription. The initial proposal by Manoury, Morel and Leredu, which focused on the ordinary soldier (“Au Poilu, la Patrie reconnaissante”), for most deputies seemed too exclusive, and they called for a wording that would include fighters from all branches of service and all military ranks. With that aim, deputy Alexandre Lefas wanted to replace the term ‘poilu’ with that of ‘héros’.21Cf. Ackermann: “Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”, 1994, 287-289; as well as Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 55 and 59f. The inscription finally chosen for the grave slab reads: “Ici / repose / un soldat / français / mort / pour la patrie // 1914–1918”. The term ‘hero’ was ultimately omitted, and yet the phrase “pour la patrie” strikes a patriotic, heroic tone.22Prost, Antoine: “Les monuments aux morts. Culte républicain? Culte civique? Culte patriotique?” In: Ageron, Charles R. / Nora, Pierre (Eds.): Les lieux de mémoire. I. La République. Paris 1984: Gallimard, 195-228, 201f., for instance proposes differentiating between civic (“monument civique”) and patriotic monuments (“monument patriotique”) for analysing monuments to the dead. While the former honour the fallen as citizens, the latter point explicitly to the military victory and sacrifice with the aid of a vocabulary from the sphere of honour, glory and heroism, such as the phrase “morts pour la Patrie”. The invoked ⟶heroic deed consists in having fallen for the fatherland, in which the semantic proximity to the sacrifice instantly manifests. Furthermore, in the use of the indefinite article ‘un’, an individual is being addressed, whereas a generic ‘le’ would have referred to an abstraction or a type.23Cf. Inglis: “Grabmäler für unbekannte Soldaten”, 1993, 158. The Unknown Soldier as a specimen was thus individualised instead of being personalised. In combination with the preserved anonymity, the individualisation allowed every single one to be honoured. By contrast to the modest design and the meagre text, the inscription on the English grave turned out to be distinctly more detailed: “Beneath this stone rest the body / of a British warrior / unknown by name or rank / brought from France to lie among / the most illustrious of the land”. Like in the French case, the indefinite article was also chosen here, yet the patriotic reminiscence is lacking, and thus the sacrifice for the fatherland as well. The term ‘soldier’ has – due to the Navy’s prestige – been replaced with the more general term ‘warrior’, and the unimportance of the name and military rank has been mentioned explicitly.

2.3. Literature as a medium of memory – two examples

Shortly after his interment beneath the Arc de Triomphe, the Unknown Soldier elicited in France an enormous literary and artistic echo that persists until the present day.24For an overview of the literary production in France cf. Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 202-214. Bertrand Tavernier’s La vie et rien d’autre from 1989 represents a later cinematic work. The literary works transcend the manifest location of the grave beneath the Arc de Triomphe to varying degrees and participate actively in the narrative of the Unknown Soldier. This article draws on Astrid Erll’s concept of literature as a ⟶medium of memory in order to be able to describe those forms of the ‘voice of the hero’ with greater nuance.

In her study Memory in Culture [Kollektives Gedächtnis und Erinnerungskulturen], Astrid Erll defines literature as a specific medium of collective memory. She distinguishes between five modes of ‘rhetoric of collective memory’ (experiential, monumental, antagonistic, historicising, reflexive) that can serve to affirm, revise and/or reflect on the dominant memory narrative. Below, two examples are presented, one that uses the experiential-monumental mode, the other the reflexive mode.25Erll, Astrid: Memory in Culture. Transl. by Sara B. Young. Houndmills/New York 2011: Palgrave Macmillan, 157-160. For a more detailed description of the five rhetoric modes cf. Erll, Astrid: Kollektives Gedächtnis und Erinnerungskulturen. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart 32017: Metzler, 167-212.

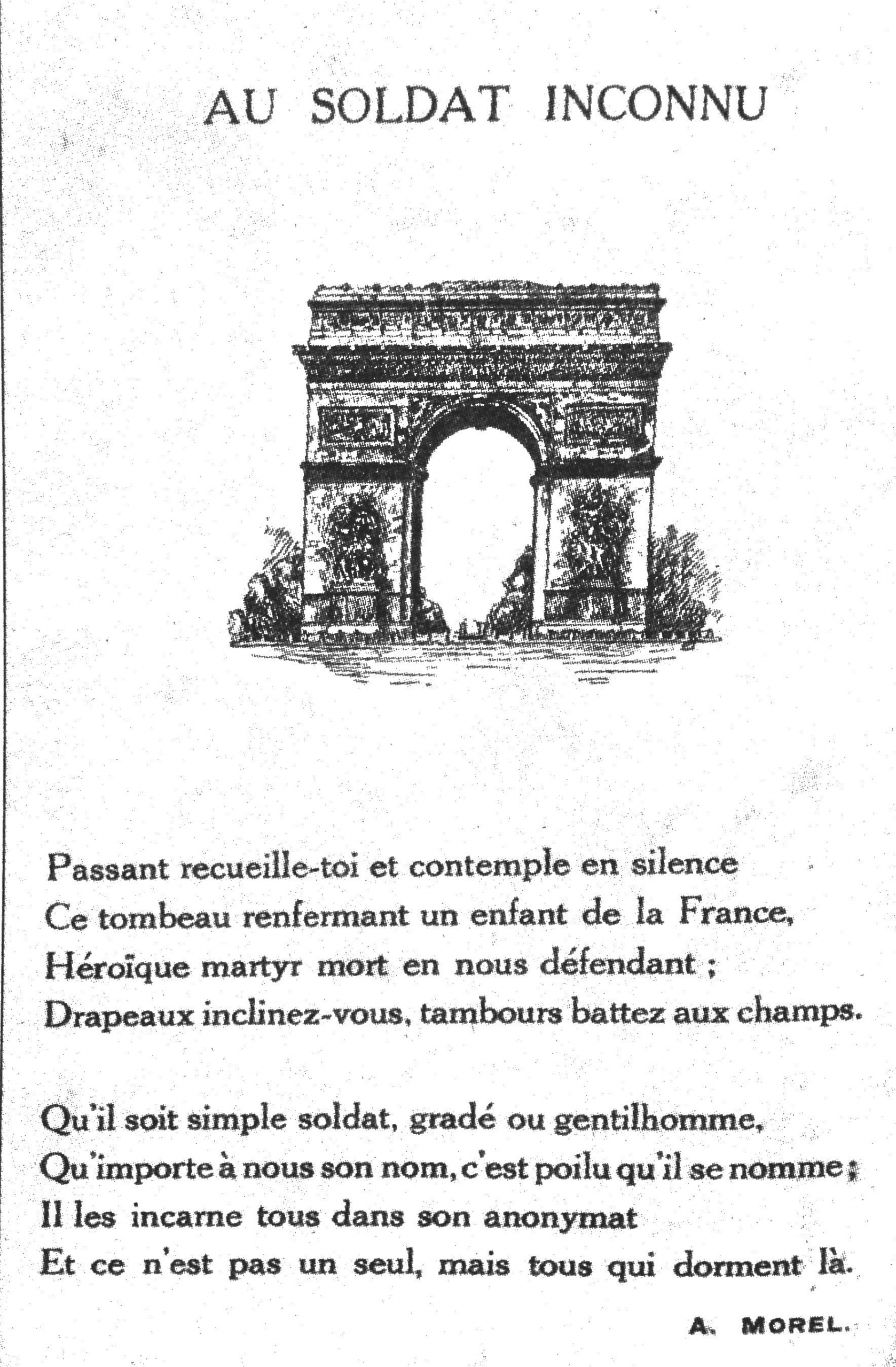

The ⟶poem Au Soldat Inconnu (undated) by Auguste Morel was published on a postcard and thus spread quickly in French society. While the title of the two-stanza Alexandrine poem comprised of rhyming couplets represents an homage to the Unknown Soldier, the first line is addressed to a passerby, who is called upon to pause and remember the interred, i.e. the Unknown Soldier. In this first stanza, the speaker imagines himself to be a member of the community of adorers (“nous”, line 3) and depicts an experiential, everyday situation. The Unknown Soldier himself is made part of the monumental portrayal in that the memorialisation of that ‘child of France’ (line 2) and that ‘heroic martyr’ (line 3) is articulated as a duty. Like in the inscription on the grave slab, the meaning of his death is seen in the defence of the fatherland (line 3). Furthermore – and the poem’s text follows the grave’s example in this respect as well – the unimportance of the name and military rank is pointed out (lines 5 f.); first and foremost, however, it is the anonymity of the Unknown Soldier that allowed the personification of not just the lost, but all the fallen in his figure and form (line 7).

In Paul Raynal’s drama Le Tombeau sous l’Arc de Triomphe (first performed in 1924 at the Comédie Française), one of the most successful and influential world war and homecomer dramas of Europe from the interwar period,26In total, the drama was staged approximately 9,000 times and the first English translation, The Unknown Warrior, was published in 1928. the Unknown Soldier appears as the protagonist.27For more on the following considerations, cf. Baumeister, Martin: “Kampf ohne Front? Theatralische Kriegsdarstellungen in der Weimarer Republik”. In: Hardtwig, Wolfgang (Ed.): Ordnungen in der Krise. Zur politischen Kulturgeschichte Deutschlands 1900–1933. Munich 2007: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 357-376; Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 206-209; Sachs, Leon / McCready, Susan: “Stages of Battle: Theater and War in the Plays of Bernhardt, Raynal, and Anouilh”. In: The French Review 87.4 (2014), 41-55. The tomb mentioned in the title alone references him metonymically; the dedication is addressed explicitly to the war’s fallen. The patriotically inspired piece is a tragedy in three acts in which the unity of place, time and action remains strictly preserved. Reduced to a few hours, it dramatises the homecoming of a front-line soldier after his fourteen-month deployment that he had purchased with his commitment to participate in a suicide mission. The drama centres on the soldier’s alienation from his fiancée and father induced by the events of the War, on the one hand, and the sounding of traditional and modern notions of war and heroism, on the other. The willingness to die for the fatherland is heroized; the masculine community in the trenches is glorified. The homecoming soldier willingly accepts the self-sacrifice as it, according to the soldier, would enable France’s resurgence on the grave of the fallen. At the beginning of the piece, he still has individual characteristics, but over the course of the piece transforms into the representative of his dead comrades and then into the symbol of all fallen French soldiers. In this respect, the drama can be seen as applying the experiential-monumental memorialisation mode. However, the piece additionally provides both an explicit and implicit “erinnerungskulturelle Selbstbeobachtung”28Erll: Kollektives Gedächtnis und Erinnerungskulturen, 32017, 192. (‘self-observation through memory culture’): a conventional memorialisation of heroes in the form of parades, speeches and obsequies is rejected as impersonal and callous, which can be interpreted as a critical reflection on the common practice of the memory culture surrounding the Unknown Soldier. Rather, a remembrance is called for that induces a genuine affective process and employs both the imagination and fiction to that end. The text thus strongly advocates the use of literature as a medium of remembrance in the national memory discourse.

That literary-artistic sources certainly have a part in shaping memory culture can be seen in this instance in particular in the expansion of the symbolic substance of the Unknown Soldierthat was due to poets’ dedication.29Cf. Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 151f.

3. Conclusion: function and function transformation

According to its origins, the Unknown Soldier was a stand-in figure for all missing soldiers who could not be buried and mourned individually by their families. Not just in France did he quickly evolve into the symbol of all the fallen in the Great War. The considerable attention that was devoted to this figure during the interwar period by the extensive, sometimes daily cultic practices observed in particular by veterans, as well as their staging at prominent, easily accessible sites such as the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, Westminster Abbey in London or the Alexander Garden near the Kremlin, and finally the uncertainty surrounding his identity paved the way for the expansion of the original meaning. All of this contributed to the Unknown Soldier transforming from the representative of the missing or, as it were, fallen soldiers ultimately into the representative of all fighting men.

4. Einzelnachweise

- 1Cf. Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink; Prost, Antoine: “Les monuments aux morts. Culte républicain? Culte civique? Culte patriotique?” In: Ageron, Charles R. / Nora, Pierre (Eds.): Les lieux de mémoire. I. La République. Paris 1984: Gallimard, 195-228; Sivan, Emmanuel / Winter, Jay M. (Eds.): War and remembrance in the twentieth century. Cambridge 1999: Cambridge University Press.

- 2Cf. Chickering, Roger: “War, society, and culture, 1850–1914: the rise of militarism”. In: Chickering, Roger / Showalter, Dennis / Ven, Hans van de (Eds.): The Cambridge History of War: War and the Modern World. Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, 124f.; Hervé Drévillon: L’individu et la Guerre. Du chevalier Bayard au Soldat inconnu. Paris 2013: Seuil, 215f.

- 3Cf. Schilling, René: “Kriegshelden”. Deutungsmuster heroischer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1813–1945. Paderborn 2002: Schöningh; Wulff, Aiko: “‘Mit dieser Fahne in der Hand’. Materielle Kultur und Heldenverehrung 1871–1945”. In: Historical Social Research 34.4 (2009), 343-355; Voss, Dietmar: „Heldenkonstruktionen. Zur modernen Entwicklungstypologie des Heroischen“. In: KulturPoetik/Journal for Cultural Poetics 11 (2011), 181-202.

- 4Cf. Ackermann, Volker: “‘Ceux qui sont pieusement morts pour la France…’ Die Identität des unbekannten Soldaten”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 281-314; Laura Wittman: The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Modern Mourning, and the Reinvention of the mystical body. Toronto 2011: Toronto University Press.

- 5Cf. Becker, Annette: Les Monuments aux morts. Mémoire de la Grande Guerre. Paris 1991: Errance.

- 6Cf. Prost, Antoine: “Le poids de la mort”. In: Cochet, François / Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (Eds.): Les soldats inconnus de la Grande Guerre. La mort, le deuil, la mémoire. Saint-Cloud 2012: Soteca, 19-42; Contamine, Philippe: „Mourir pour la patrie“. In: Babelon, Jean-Pierre / Nora, Pierre (Eds.): Les lieux de mémoire. II. La Nation. Paris 1986: Gallimard, 11-43.

- 7Cf. Gilzmer, Mechtild: “‘A nos morts.’ Wandlungen im Totenkult vom 19. Jahrhundert bis heute”. In: Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred (Eds.): Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich. Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung. Munich 2013: Oldenbourg, 175-198; Goebel, Stefan: “Brüchige Kontinuität. Kriegerdenkmäler und Kriegsgedenken im 20. Jahrhundert”. In: Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred (Eds.): Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich. Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung. Munich 2013: Oldenbourg, 199-224; Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred: “Heroisierung und Opferstilisierung. Grundelemente des Gefallenengedenkens von 1813 bis heute”. In: Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred (Eds.): Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich. Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung. Munich 2013: Oldenbourg, 123-158.

- 8Cf. Assmann, Jan: Das kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. Munich 72013: Beck, 138-140.

- 9Cf. Assmann, Jan: “Die Lebenden und die Toten”. In: Assmann, Jan (Ed.): Der Abschied von den Toten. Trauerrituale im Kulturvergleich. Göttingen 22007: Wallstein, 16-36.

- 10Cf. Winter, Jay M.: “Forms of kinship and remembrance in the aftermath of the Great War”. In: Sivan, Emmanuel / Winter, Jay M. (Eds.): War and remembrance in the twentieth century. Cambridge 1999: Cambridge University Press, 40-60; Beaupré, Nicolas: Das Trauma des Großen Krieges 1918–1932/33. Darmstadt 2009: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft; Becker, Annette: “Der Kult der Erinnerung nach dem Großen Krieg. Kriegerdenkmäler in Frankreich”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 315-324.

- 11Cf. Becker: “Der Kult der Erinnerung nach dem großen Krieg”, 1994, 315-324; Janz, Oliver: Das symbolische Kapital der Trauer. Nation, Religion und Familie im italienischen Gefallenenkult des Ersten Weltkriegs. Tübingen 2009: Niemeyer, 2-11; Inglis, Ken: “Entombing Unknown Soldiers: From London and Paris to Baghdad”. In: History and Memory 5.2 (1993), 7-31; Ziemann, Benjamin: “Die deutsche Nation und ihr zentraler Erinnerungsort: Das ‘Nationaldenkmal für die Gefallenen im Weltkriege’ und die Idee des ‘Unbekannten Soldaten’ 1914–1935”. In: Berding, Helmut (Ed.): Krieg und Erinnerung. Fallstudien zum 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Göttingen 2000: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 67-92.

- 12Cf. Wardhaugh, Jessica: “Fighting for the Unknown Soldier: The Contested Territory of the French Nation in 1934–1938”. In: Modern & Contemporary France 15 (2007), 185-201; Correia, Sílvia: “Death and Politics: The Unknown Warrior at the Center of the Political Memory of the First World War in Portugal”. In: E-Journal of Portuguese History 11 (2013), 6-29.

- 13Cf. Ackermann, Volker: “‘Ceux qui sont pieusement morts pour la France…’. Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 281-314, 284.

- 14A detailed description of the genesis of the idea of the Unknown Soldier and the selection of the corpse and its burial can be found in Jagielski, Jean-François: Le Soldat inconnu. Invention et postérité d’un symbole. Paris 2005: Imago, 51-124; und Ackermann, “Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”, 1994.

- 15In this respect, cf. Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 171f.

- 16Cf. Giesen, Bernhard: Triumph and Trauma. Boulder/London 2004: Paradigm, 25-36.

- 17Cf. Ackermann: “Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”, 1994, 291-296, esp. 295f.

- 18In the words of deputy Charles Dumont, quoted according to Jagielsi: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 74: “[L]e poilu que nous allons glorifier n’est pas un de ces grands hommes. Il est le symbole de la foule immense des soldats qui se sont sacrifiés pour la Patrie.” (“The poilu we will be honouring is not one of these great men. He is the symbol of the immense number of soldiers who sacrificed themselves for the fatherland.”)

- 19Cf. Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 73.

- 20Cf. Inglis: “Grabmäler für unbekannte Soldaten”, 1993, 157, as well as La Naour, Jean-Yves: “Le soldat inconnu: Une histoire polémique”. In: Cochet, François / Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (Eds.): Les Soldats inconnus de la Grande Guerre: la mort, le deuil, la mémoire. Saint-Cloud 2012: Soteca, 307-321, 316f.

- 21Cf. Ackermann: “Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”, 1994, 287-289; as well as Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 55 and 59f.

- 22Prost, Antoine: “Les monuments aux morts. Culte républicain? Culte civique? Culte patriotique?” In: Ageron, Charles R. / Nora, Pierre (Eds.): Les lieux de mémoire. I. La République. Paris 1984: Gallimard, 195-228, 201f., for instance proposes differentiating between civic (“monument civique”) and patriotic monuments (“monument patriotique”) for analysing monuments to the dead. While the former honour the fallen as citizens, the latter point explicitly to the military victory and sacrifice with the aid of a vocabulary from the sphere of honour, glory and heroism, such as the phrase “morts pour la Patrie”.

- 23Cf. Inglis: “Grabmäler für unbekannte Soldaten”, 1993, 158.

- 24For an overview of the literary production in France cf. Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 202-214. Bertrand Tavernier’s La vie et rien d’autre from 1989 represents a later cinematic work.

- 25Erll, Astrid: Memory in Culture. Transl. by Sara B. Young. Houndmills/New York 2011: Palgrave Macmillan, 157-160. For a more detailed description of the five rhetoric modes cf. Erll, Astrid: Kollektives Gedächtnis und Erinnerungskulturen. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart 32017: Metzler, 167-212.

- 26In total, the drama was staged approximately 9,000 times and the first English translation, The Unknown Warrior, was published in 1928.

- 27For more on the following considerations, cf. Baumeister, Martin: “Kampf ohne Front? Theatralische Kriegsdarstellungen in der Weimarer Republik”. In: Hardtwig, Wolfgang (Ed.): Ordnungen in der Krise. Zur politischen Kulturgeschichte Deutschlands 1900–1933. Munich 2007: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 357-376; Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 206-209; Sachs, Leon / McCready, Susan: “Stages of Battle: Theater and War in the Plays of Bernhardt, Raynal, and Anouilh”. In: The French Review 87.4 (2014), 41-55.

- 28Erll: Kollektives Gedächtnis und Erinnerungskulturen, 32017, 192.

- 29Cf. Jagielski: Le soldat inconnu, 2005, 151f.

5. Selected literature

- Ackermann, Volker: “‘Ceux qui sont pieusement morts pour la France…’. Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 281-314.

- Assmann, Jan: “Die Lebenden und die Toten”. In: Assmann, Jan (Ed.): Der Abschied von den Toten. Trauerrituale im Kulturvergleich. Göttingen 22007: Wallstein, 16-36.

- Becker, Annette: Les Monuments aux morts. Mémoire de la Grande Guerre. Paris 1991: Errance.

- Cochet, François / Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (Eds.): Les Soldats inconnus de la Grande Guerre. La mort, le deuil, la mémoire. Saint-Cloud 2012: Soteca.

- Contamine, Philippe: “Mourir pour la patrie”. In: Babelon, Jean-Pierre / Nora, Pierre (Eds.): Les lieux de mémoire. II. La Nation. Paris 1986: Gallimard, 11-43.

- Correia, Sílvia: “Death and Politics. The Unknown Warrior at the Center of the Political Memory of the First World War in Portugal”. In: E-Journal of Portuguese History 11 (2013), 6-29.

- Echternkamp, Jörg / Hettling, Manfred (Eds.): Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich. Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung. Munich 2013: Oldenbourg.

- Erll, Astrid: Kollektives Gedächtnis und Erinnerungskulturen. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart 32017: Metzler.

- Erll, Astrid: Memory in Culture. Transl. by Sara B. Young. Houndmills/New York 2011: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Giesen, Bernhard: Triumph and Trauma. Boulder/London 2004: Paradigm.

- Inglis, Ken: “Entombing Unknown Soldiers. From London and Paris to Baghdad”. In: History and Memory 5.2 (1993), 7-31.

- Inglis, Ken: “Grabmäler für unbekannte Soldaten”. In: Stölzl, Christoph (Ed.): Die neue Wache unter den Linden. Ein deutsches Denkmal im Wandel der Geschichte. Munich/Berlin 1993: Koehler & Amelang, 150-171.

- Jagielski, Jean-François: Le Soldat inconnu. Invention et postérité d’un symbole. Paris 2005: Imago.

- Janz, Oliver: Das symbolische Kapital der Trauer. Nation, Religion und Familie im italienischen Gefallenenkult des Ersten Weltkriegs. Tübingen 2009: Niemeyer.

- Julien, Ilse: “Paris und Berlin nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Eine symbolische Nationalisierung der Hauptstädte?” In: Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift 73.1 (2014), 51-88.

- Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink.

- La Naour, Jean-Yves: “Le soldat inconnu. Une histoire polémique”. In: Cochet, François / Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (Eds.): Les Soldats inconnus de la Grande Guerre. La mort, le deuil, la mémoire. Saint-Cloud 2012: Soteca, 307-321.

- Mosse, George L.: Gefallen für das Vaterland. Nationales Heldentum und namenloses Sterben. Übers. von Udo Rennert. Stuttgart 1993: Klett-Cotta.

- Prost, Antoine: “Les monuments aux morts. Culte républicain? Culte civique? Culte patriotique?” In: Ageron, Charles R. / Nora, Pierre (Eds.): Les lieux de mémoire. I. La République. Paris 1984: Gallimard, 195-228.

- Wardhaugh, Jessica: “Fighting for the Unknown Soldier. The Contested Territory of the French Nation in 1934–1938”. In: Modern & Contemporary France 15 (2007), 185-201.

- Wittman, Laura: The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Modern Mourning, and the Reinvention of the mystical body. Toronto 2011: University of Toronto Press.

- Ziemann, Benjamin: “Die deutsche Nation und ihr zentraler Erinnerungsort. Das ‘Nationaldenkmal für die Gefallenen im Weltkriege’ und die Idee des ‘Unbekannten Soldaten’ 1914–1935”. In: Berding, Helmut (Ed.): Krieg und Erinnerung. Fallstudien zum 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Göttingen 2000: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 67-92.

6. List of images

- 1Tombe du Soldat inconnu, unter dem Triumphbogen in ParisQuelle: Foto von Isabell Oberle, 2018Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-ND 4.0

- 2Auguste Morel: Au Soldat Inconnu (o. J.), Faksimile einer Postkarte, auf der das Gedicht verbreitet wurde.Quelle: publiziert in Jagielski, Jean-François: Le Soldat inconnu. Invention et postérité d’un symbole. Paris 2005: Imago, 142.Lizenz: Gemeinfrei

- 3Frontispiz zu Paul Raynal: Le Tombeau sous l’Arc de Triomphe.Quelle: Paul Raynal: Le Tombeau sous l’Arc de Triomphe. Tragédie en trois actes. 26. Aufl. Paris 1928: Stock.Lizenz: Zitat eines urheberrechtlich geschützten Werks (§ 51 UrhG)