- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 28. Juni 2024

Inhalt

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Dealing with colonial heroes

- 2.1. Dismantling colonial heroes

- 2.2. Appropriation, reinterpretation and revival of colonial heroes

- 2.2.1. Humanitarian heroes

- 2.2.2. Revival of colonial heroes

- 2.2.3. Competing colonialisms

- 3. Anticolonial heroes

- 3.1. Heroes of the liberation struggle

- 3.1.1. Heroization of the victors and new rulers

- 3.1.2. The potential for deheroization inherent in the ‘strong men’

- 3.1.3. Exclusion from heroization

- 3.2. Martyrs

- 3.3. Proto-freedom fighters

- 3.4. Mythological heroes

- 4. Structural issues

- 4.1. Official and private commemoration of heroes

- 4.1.1. State cults of heroes

- 4.1.2. Counter-narratives, privatisation and diversification

- 4.2. Global heroes

- 4.3. Violence

- 4.4. Gender

- 5. Research perspectives

- 6. Einzelnachweise

- 7. Selected literature

- 8. List of images

- Citation

1. Introduction

‘Decolonisation’ refers to both the developments leading to the termination of a colonial rule and the political, social and economic transformations triggered by its end and subsequent independence.1This article is adapted from the 2018 German article ⟶Dekolonisation in Compendium heroicum. The term raises questions of demarcation in terms of time, geography and substance. This article follows Jürgen Osterhammel’s suggestion to narrowly define the term decolonisation and position it in 20th-century history as “(1) the simultaneous dissolution of several intercontinental empires […] within a short time span of roughly three postwar decades (1945–75), linked with (2) the historically unique and, in all likelihood, irreversible delegitimization of any kind of political rule that is experienced as a relationship of subjugation to a power elite considered by a broad majority of the population as alien occupants.”2Osterhammel, Jürgen / Jansen, Jan C.: Decolonization. A short history. Transl. by Jeremiah Riemer. Princeton / Oxford 2017: Princeton University Press, 1f.

Decolonisation was closely tied to the emergence of new nations. It can also be understood as the final major wave of nation-state formation, occurring at a time when the idea of the nation-state had reached its pinnacle with no viable alternatives left.3Cf. Anderson, Benedict: Die Erfindung der Nation. Zur Karriere eines folgenreichen Konzepts. Berlin 1998: Ullstein, 100-121. Within the process of nation-building, ⟶heroic figures were of great importance as part of a national narrative and national memory to create identification and cohesion (cf. ⟶national hero). ⟶Heroization, deheroization and the reinterpretation of ⟶hero narratives were decisively shaped by the relationship with the former colonial power and the achievement of independence. In the vast majority of cases, the separation from the former colonial power was marked by ⟶violence4Cf. Osterhammel, Jürgen / Jansen, Jan C.: Dekolonisation. Das Ende der Imperien. Munich 2013: C.H. Beck, 9.; the significance of military, mostly male, forms of heroism and potential alternative heroization strategies therefore call for particular attention.

2. Dealing with colonial heroes

2.1. Dismantling colonial heroes

In many colonies, colonial powers, especially Great Britain and France, pursued an active policy of heroization. This was particularly pronounced in Africa. Since pre-colonial Africa was considered to be less civilised and much of its interior remained terra incognita to Europeans until the 19th century, the achievements of Europeans as explorers, conquerors, civilisers, missionaries, humanitarian helpers, and constructors of modern societies could be highlighted. Colonial heroes were made, for example, through toponymy, the naming of institutions and the erection of monuments.5Cf. fundamental to this Sèbe, Berny: Heroic Imperialists in Africa. The Promotion of British and French Colonial Heroes, 1870–1939. Manchester 2013: Manchester University Press. The heroization of colonisers as symbols of their humanitarian mission became all the more important when resistance arose among the population and was fought with means that contradicted all humanitarian principles of international law.6Cf. Malinowski, Stephan: “Modernisierungskriege. Militärische Gewalt und koloniale Modernisierung im Algerienkrieg (1954–1962)”. In: Kruke, Anja (Ed.): Dekolonisation. Prozesse und Verflechtungen 1945–1990. Bonn 2009: Dietz, 213-248.

In numerous states, especially those undergoing violent decolonisation processes, the desire for a radical break with the colonial past led to the post-independence removal of colonial figures from the national heroic memory. Some of them were redefined as ⟶anti-heroes, such as the British officers Charles George Gordon (1833–1885) and Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850–1916) in Sudan; this simultaneously made it possible to reinterpret any local opposition to them as part of the national liberation struggle. Even European heroic figures who were not directly involved in colonial conquests or the violent suppression of resistance were now regarded as foreign heroes, whose ⟶adoration was at best to be undertaken by Europeans, while they were to make way for locally rooted heroes in the heroic cosmos of the new nation-state.7Cf. Sèbe, Berny: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation-Building? British and French Imperial Heroes in Twenty-First-Century Africa”. In: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42.5 (2014), 936-968, 936.

As the most visible manifestation of the dismantling of colonial heroes, statues were removed in many places, such as the equestrian statue of Marshal Bugeaud (1784–1849), the conqueror of Algeria, in Algiers, or the statue depicting General Gordon on a camel in Khartoum (cf. fig. 1). Additionally, there were numerous renaming initiatives.8Cf. Trotman, David V.: “Acts of Possession and Symbolic Decolonisation in Trinidad and Tobago”. In: Caribbean Quarterly 58.1 (2012), 21-43. This included streets, institutions like Gordon College and the Kitchener School of Medicine in Khartoum, which became the University of Khartoum, and entire states such as Northern and Southern Rhodesia, renamed Zambia and Zimbabwe respectively upon independence.9Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation-Building?”, 2014, 940-945. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the capital Leopoldville was renamed Kinshasa. Stanleyville, named after Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904), who had first explored and then acquired the Congo for the Belgian King Leopold, and Stanley Pool were also renamed; Stanley’s colossal statue in Kinshasa was toppled. A highly symbolic photograph by Guy Tillim shows how the larger-than-life figure, broken off above the ankles, was dumped on a waste ground on a rusty boat against which a boy urinates (cf. fig. 2); an ambiguous staging conveying both indifference and contempt.10Berenson, Edward: Heroes of Empire. Five Charismatic Men and the Conquest of Africa. Berkeley / Los Angeles 2011: University of California Press, 273. Distinguishing between these two perspectives is not always easy, for the attempt to radically distance oneself from colonial heroes was neither comprehensive, consistent, nor linear. In many places, colonial heroizations were tacitly continued, possibly out of a lack of political will to remove them or out of indifference.11Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 2014, 945-946. In other cases, colonial hero narratives were actively reinterpreted or revived after a period of rejection or marginalisation.

2.2. Appropriation, reinterpretation and revival of colonial heroes

2.2.1. Humanitarian heroes

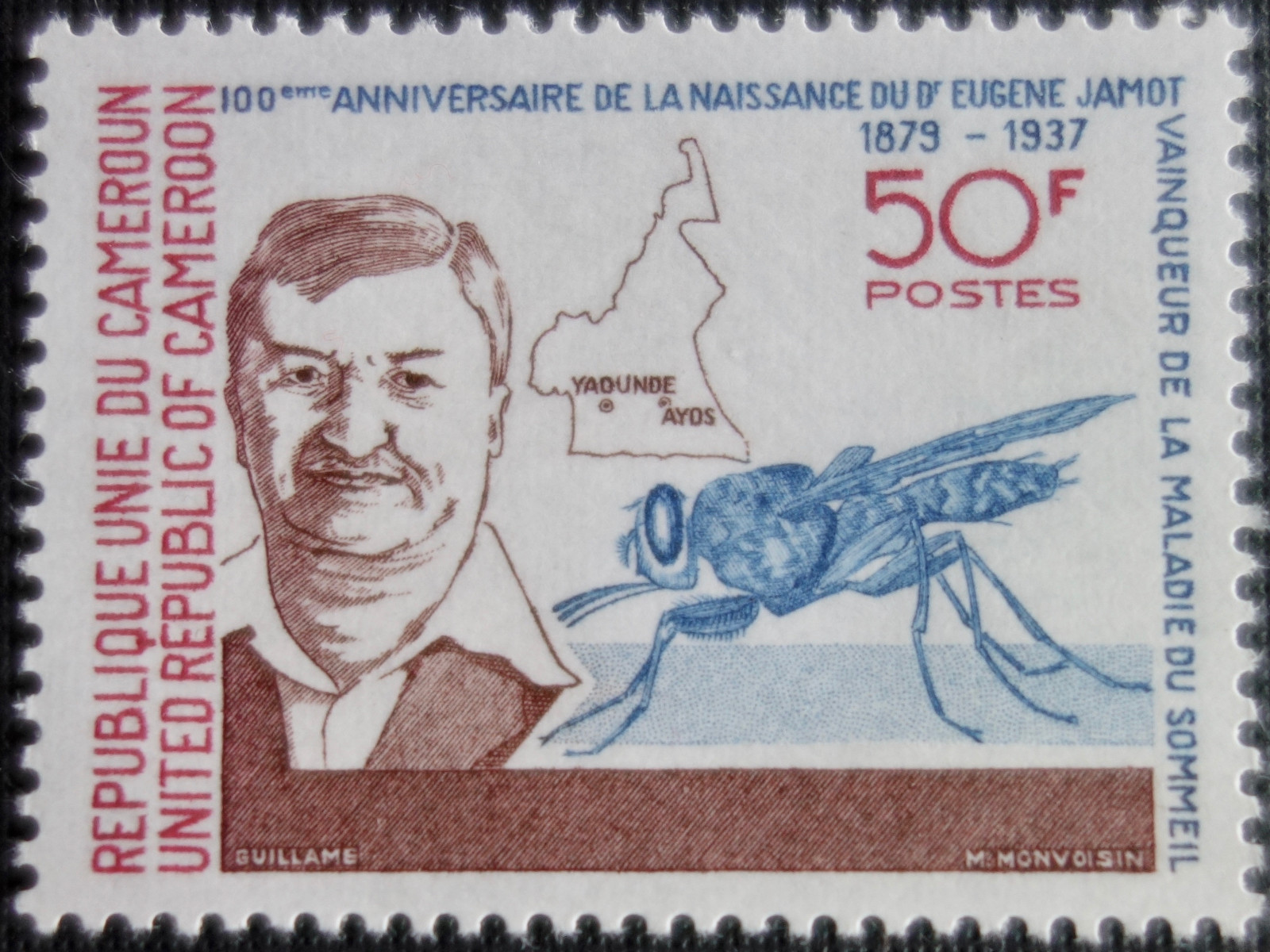

Numerous colonial heroes were perceived as ambiguous figures who had obvious merits, such as improving the supply and infrastructure of a colony or the abolition of slavery, while at the same time having actively supported a colonial regime. This tension is particularly pronounced in the case of heroes who established medical care under a colonial regime, earned humanitarian praise and often made great personal sacrifices. In the post-colonial era, they were exposed to criticism for having placed themselves at the service of a ‘civilising mission’, conducted faith missions and implemented paternalistic concepts of value and order, particularly regarding race or mental illness. Often, this tension and the controversial status of these figures and their work resulted in a reserved or ambivalent culture of remembrance instead of a radical distancing. For example, although the French doctor Eugène Jamot (1879–1937), who dedicated himself to combating sleeping sickness in Cameroon, is far from being a national hero, a statue is dedicated to him in Yaoundé, at the eponymous hospital.12Cf. Taithe, Bertrand / Davis, Katherine: “‘Heroes of Charity?’ Between Memory and Hagiography: Colonial Medical Heroes in the Era of Decolonisation”. In: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42.5 (2014), 912-935, 923-924. Additionally, the state of Cameroon issued a stamp in his honour on his 100th birthday (cf. fig. 3).

The Alsatian doctor Albert Schweitzer (1875–1965), founder of the hospital in Lambaréné in Gabon and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, is incomparably more famous. His house and grave are memorials today and the State of Gabon dedicated stamps to him (cf. fig. 4). Upon his death, the then President of Gabon, Léon M’ba, urged that his work never be forgotten. Below the surface of official commemoration, however, in Gabon Schweitzer is the subject of not only hagiographic reflections but also satirical criticism.13Cf. Taithe / Davis: “‘Heros of Charity?’” 2014, 924-926. The latter is expressed, for example, in the film Le Grand Blanc de Lambaréné (Gabon 1994), which deconstructs Schweitzer’s heroic status by tracing a process of disillusionment from the perspective of a young African admirer. At the centre of the hero’s dismantling is his disinterest in African culture and indigenous languages and his lack of understanding of the growing independence movement, which render him a hero unfit for the new postcolonial era.14Cf. Koplik, Mark: “Le Grand Blanc de Lambaréné”. In: Film Notes. Online at: https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst/webpages4/filmnotes/fns98n4.html (accessed on 02.03.2018). (See also ⟶debunking.)

2.2.2. Revival of colonial heroes

In the course of decolonisation, some colonial heroic figures in Africa were initially marginalised from national memory, but rediscovered at the beginning of the 21st century. The growing distance to the colonial era allowed for greater emotional detachment in dealing with their legacy and led to an increased willingness to understand them as part of national history. In addition, in many former colonial African states, a disillusionment with the heroes of the struggle for independence could be observed, whose adoration was eclipsed by the perception of corruption, dictatorial rule and a lack of successful development. An increasingly global orientation on the part of many African elites also led to a desire for a more cosmopolitan national narrative.

In this context, the renewed heroization of colonial heroic figures offered a variety of advantages. Many states used it in order to further their goal of strengthening economic and political relations with former colonial powers. Hopes for an increase in tourism from Europe also contributed to maintaining, restoring or even building new memorials to colonial heroes. In states where Christianity was the dominant religion, the motive of commemorating the spread of Christianity additionally favoured the heroization of colonial figures. All these aspects came into play during the commemoration of the bicentenary of David Livingstone’s birth (1813–1873), which was solemnly celebrated in Zambia under the auspices of a committee set up in the town of Livingstone. Even the creation of colonial frontiers could be celebrated as a milestone in national history in the context of a series of anniversaries, such as in Nigeria, where a European colonial official was elevated to the status of national hero.15Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 2014, 946-951.

A particularly striking example of this form of heroic commemoration is the erection of a prestigious monument memorialising Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza (1852–1905), the founder of the French colony of Congo, in the capital Brazzaville. In the Republic of Congo, Brazza’s memory has been consistently framed in a positive manner while attempts of deconstruction failed to materialise.16Cf. Berenson: Heroes of Empire, 2011, 275. The foundation stone for the white marble building was laid in 2005 in the presence of French President Jacques Chirac. The memorial, including a six-metre-high statue of the hero, was completed in less than a year, after which the mortal remains of Brazza, his wife and children were transferred to the crypt. In the divided country, marked by ethnic and linguistic diversity, wars, poverty and corruption, in which the anti-colonial ‘strong men’ of the 1970s no longer held any appeal, the memory of this external hero was intended to unify and establish a connection to Europe.17Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 2014, 953-962; Berenson: Heroes of Empire, 2011, 283-285.

In Mali, during a phase of successful democratisation and a relatively tension-free relationship with the former colonial power, France, President Alpha Oumar Konaré (1992–2002) initiated the construction of a grand ensemble in honour of French ‘explorers’ and ‘regents’ in Bamako. Numerous sculptures were to commemorate this era of the country’s history, including a statue of Gustave Borgnis-Desbordes (1839–1900), one of the conquerors of French Sudan (cf. fig. 5). However, the case of Mali also illustrates the conflicts that state appropriation of colonial heroes can trigger. Parts of the public strongly opposed the revival of the colonial legacy and viewed the glorification of violent conquerors and foreign rulers as misguided (cf. source 1). In the town of Ségou, protests occurred that pursued an entirely different agenda. The population objected to the relocation of a statue of General Louis Archinard (1850–1932), the city’s conqueror and first governor of French Sudan, to Bamako. Although the statue had been dismantled after independence and Boulevard Archinard renamed, the successful protests against its transfer to Bamako led to its restoration and its re-installation in Ségou with the help of donations from France.18Cf. Jorio, Rosa de: “Politics of Remembering and Forgetting. The Struggle over Colonial Monuments in Mali”. In: Africa Today 52.4 (2006), 79-106; Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 952-953. In this case, the protest was not directed against the commemoration of a representative of the colonial power, but against its centralisation.

“In the 1940s and 1950s, in secondary school, history that was taught to pupils consisted in honouring the heroes of colonisation in the following way: Bugeaud in Algeria, Faidherbe in Senegal, Lyautey in Morocco, Gallieni in Madagascar, Savorgnan de Brazza in the Congo. These mnemonic methods devised by teachers who had no doubts about the benefits of colonisation violated outrageously the conscience of our young children. I would like to know the Malian who came with the idea of excavating the inmost depths of history to bring back to the surface this refuse which history had condemned and buried. He could as well had asked us to weave laurel wreaths for Gallieni, Rebenne, Colonel Bonnier, Robard, Roccasséra, Renaud and others.”

Samba Sow, Erection du monument Archinard à Ségou: l’acte inqualifiable du gouverneur Abou Sow, L’Indépendant, 26 Feb. 2009.

Source: Sèbe, Berny: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation-Building? British and French Imperial Heroes in Twenty-First-Century Africa”. In: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42.5 (2014), 958.

2.2.3. Competing colonialisms

In some countries of Southeast Asia, there is evidence of a recurring reevaluation and valorisation of the British military, particularly in relation to World War II. In what is now Myanmar and Malaysia, Japan replaced Great Britain as the colonial power, leading to hardships for the local military and civilian population, including massacres by the Japanese army. The rejection of the Japanese occupation by the population forms the backdrop to the emergence of rituals of heroic commemoration of British military personnel who fought against Japan in Southeast Asia, a practice that continues until this day. This case illustrates that competing narratives of occupation and oppression can lead to surprising heroizations of representatives of a former colonial power or locals associated with them.19Cf. “How a Forgotten British Captain is a Hero in Myanmar”. In: BBC News, 31 January 2016. Online at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-35192153 (accessed on 02.03.2018); Gray, Denis, D.: “Hero’s Commemoration Links WWII with Rohingya Crisis”. In: Nikkei Asian Review, 25 November 2017. Online at: https://asia.nikkei.com/Life-Arts/Life/Hero-s-commemoration-links-WWII-with-Rohingya-crisis (accessed on 02.03.2018); “British Heroes of Sandakan Remembered”. In: The Star Online, 29 August 2011. Online at: https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2011/08/29/british-heroes-of-sandakan-remembered/ (accessed on 02.03.2018); Mokhtar, Mariam. “The Forgotten M’sian Heroine: Sybil Kathigasu”. In: Hornbill Unleashed, 13 June 2010. Online at: https://hornbillunleashed.wordpress.com/2010/06/13/7532/ (accessed on 02.03.2018). In contrast, in Indonesia, where the Netherlands fought a bloody war of independence lasting several years after Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, there was no room for such heroization of Europeans; here, only indigenous independence fighters were declared heroes.

3. Anticolonial heroes

The attainment of independence in the former colonies triggered the need for a systematic reorganisation of the topography and rhetoric of public commemoration, including hero worship. The form and tools of this commemoration often differed little from the kind of “political musealisation” previously employed by colonial powers through monuments as well as the (re)naming of cities and streets.20Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 2014, 945-946. See also Anderson: Die Erfindung der Nation, 1998, 157. It was therefore logical that after independence, one of the central squares of Algiers, Algeria, hitherto named after the French conqueror Marshal Bugeaud, was renamed after the Algerian independence hero Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza’iri (1808–1883). In addition, the equestrian statue of Marshal Bugeaud was replaced by an equestrian statue of Abd al-Qadir, his adversary (cf. fig. 6).21Jansen, Jan C.: “Creating National Heroes. Colonial Rule, Anticolonial Politics and Conflicting Memories of Emir ‘Abd al-Qadir in Algeria, 1900–1960s”. In: History and Memory 2.3 (2016), 3-46, 3-4.

The heroic narratives constructed and promoted (mostly) by state actors after independence played a central role in nation building. They were of particular importance as unifying symbols in territories, that had no continuous history as a political or cultural entity nor a common language, but emerged from colonial boundaries. The heroic narratives served to define and make tangible the nation’s identity as opposed to colonialism, which was viewed as foreign domination and had been overthrown.

Several types of heroic figures were promoted in decolonised states after independence. They were elevated to the rank of national symbols through toponymy, statues, commemorative events, museums, and mausoleums. These types are not mutually exclusive, but often coexisted, their respective prominence depending on the historical context. Each of them entails its own set of advantages and challenges.

3.1. Heroes of the liberation struggle

3.1.1. Heroization of the victors and new rulers

A widespread strategy of heroization focused on victorious independence fighters who assumed political power in the new nation-states. Consequently, many African states that gained independence were governed by “strong men”, who derived their legitimacy from their successful resistance against colonial rulers and the persecution they had endured. As a matter of fact, the lives of these figures had often been entangled in colonial structures, having been educated in colonial institutions where they were exposed to nationalist ideas.22Cf. Anderson: Die Erfindung der Nation, 1998, 113-114. Later, they vehemently opposed colonial rule, ⟶enduring imprisonment or exile before ultimately seizing power following independence.

Kenneth Kaunda (1924–2021) is a typical representative of this model. He became active for the African National Congress (ANC) in Northern Rhodesia in the early 1950s and was sent to jail for two months in 1955 for distributing anti-British literature, followed by a nine-month prison sentence in 1959. In the early 1960s, he organised a campaign of civil disobedience that included acts of arson. When Zambia achieved independence, he became the country’s first president, ruling autocratically for 27 years in a system tailored entirely to him and his vision of ‘Zambian humanism’, which was framed as non-aligned, but was economically strongly modelled after the socialist states.23Melady, Thomas Patrick / Melady, Margaret Badum: Ten African Heroes. The Sweep of Independence in Black Africa. Maryknoll 2011: Orbis, 49-68. Kaunda built himself up as a hero, symbol and guarantor of national unity and it was the national media’s – especially the radio’s – main task to propagate this image of him.24Cf. Heinze, Robert: “‘Decolonising the Mind’. Nationalismus und Nation Building im Rundfunk in Namibia und Sambia”. In: Kruke, Anja (Ed.): Dekolonisation. Prozesse und Verflechtungen 1945–1990. Bonn 2009: Dietz, 295-316, 306-309.

The situation was somewhat different in the Republic of Indonesia, which was proclaimed independent in 1945 and recognised by the Netherlands after a four-year war. Sukarno (1901–1970), the leader of the independence movement, became the first president. He, too, was a dictator who deliberately used his status as a liberator from colonial rule to bolster his legitimacy. However, he broadened the scope of hero worship. Specifically, he introduced the state designation “National Independence Hero”, which was exclusively awarded posthumously, aiming to establish a heroic narrative that would resonate throughout the young nation of Indonesia. It also had the effect of heroizing Sukarno, the country’s supreme leader, by proxy. The sacrifices made by fallen fighters were supposed to foster national identification and strengthen the fragile state. Sukarno himself was posthumously awarded the ⟶title “Proclamation Hero”.25Cf. Scagliola, Stef: “The Silences and Myths of a ‘Dirty War’: Coming to Terms with the Dutch–Indonesian Decolonisation War (1945–1949)”. In: European Review of History 14.2 (2007), 235-262, 245-246; Artaria, Myrtati Dyah: “Heroes and Heroines”. In: Lee, Jonathan H. X. / Nadeau, Kathleen (Eds.): Encyclopaedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara 2011: ABC Clio, 538-540.

3.1.2. The potential for deheroization inherent in the ‘strong men’

The heroization of independence fighters who transformed into strongmen frequently posed difficulties. As successful as they may have been as young men in liberating their countries from colonial power, their often decades-long actions as dictators frequently led to disillusionment. Although they had access to the state ⟶propaganda apparatus, it could not indefinitely mask the realities of corruption, poverty and unfulfilled promises of progress.

Gamal Abd al-Nasser (1918–1970), an icon of the Arab world, took a particularly dramatic fall. Although Egypt had gained formal independence before the Second World War, it remained heavily dependent on the former protectorate power Great Britain until the 1950s. Nasser’s central role in the Free Officers’ coup of 1952 against the monarchy which symbolised this dependency, and the successful nationalisation of the Suez Canal in 1956, made him a hero of decolonisation and a key figure in the movement of non-aligned states. However, the devastating military defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War, which also shattered the promise of a post-colonial nation-state for the Palestinians, almost completely demystified Nasser:

“The charismatic relationship between [Abdel Nasser] and the masses formed during the bright youthful days of Bandung and Suez, was shattered with the defeat; another variant born out of despair and a sense of loss, sustained him until his death. He would stay in power not as a confident, vibrant hero, but as a tragic figure, a symbol of better days, an indication of the will to resist.”26Ajami, Fouad: The Arab Predicament. Arab Political Thought and Practice since 1967. London 1981: Cambridge University Press, 85.

Similar processes of disillusionment have led to criticism of former leaders of independence movements in many postcolonial societies. The processes by which freedom fighters became dictators and thus turned from victims into perpetrators are now being examined more closely in some places. In some cases, this scrutiny leads to a questioning of heroic narratives as a whole.27Cf. Melber, Henning: “Limits to Liberation. An Examination of Namibia’s Post-Colonial Culture”. In: Melber, Henning (Ed.): Re-Examining Liberation in Namibia. Political Culture since Independence. Uppsala 2003: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 9-24, 11. For the most part, however, the criticism leads to the prioritisation of alternative heroes and hero types, especially those that have been marginalised in official historiography thus far.

3.1.3. Exclusion from heroization

The heroization of independence fighters was usually selective. Hero status was primarily conferred upon the new rulers and those associated with them or those who could be appropriated without risk. Independence fighters who opposed the new rulers or were not ideologically compatible with them were ignored or even persecuted. Compatibility was sometimes assessed through personal ties or ethnic criteria, but often also according to the overarching framework of the Cold War. For example, after Cameroon’s independence in 1960, the leftist Union des Populations de Cameroun (UPC) continued its armed struggle against the new government, accusing it of perpetuating colonial rule. Therefore, figures like UPC leader Ruben Um Nyobé (1913–1958), who was killed by the French army in 1958, were not publicly commemorated as heroes. The last UPC leader to lead the guerrilla struggle, Ernest Ouandié (1924–1971), was executed by the Cameroonian government in 1971. In the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, the ban on the UPC was lifted and the Parliament of Cameroon conferred the title of “National Heroes” on its deceased leaders. Nevertheless, they initially hardly played a role in official historiography. In the 2000s, this began to change: In 2007, a statue was erected in Um Nyobé’s birthplace Eséka (cf. fig. 7) and a monument and a boulevard named after him were also being planned in Douala. These rather reluctant acts of heroization appear to be a response to pressure from civil society.28Cf. Ya Kama, Lisapo: “Um Nyobe, the Forgotten Father of the Independence of Cameroon”. In: African History. Histoire Africaine. Online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20191231143009/http://en.lisapoyakama.org/um-nyobe-the-forgotten-father-of-the-independence-of-cameroon (accessed on 27.06.2024); Dr. Y.: “Ruben Um Nyobé: Fighting for the Independence of Cameroon”. In: African Heritage, 2011. Online at: https://afrolegends.com/2011/10/10/ruben-um-nyobe-fighting-for-the-independence-of-cameroon/ (accessed on 06.03.2018); Dr. Y.: “Ernst Ouandié: A Cameroonian and African Hero and Martyr”. In: African Heritage, 2018. Online at: https://afrolegends.com/2018/01/15/ernest-ouandie-a-cameroonian-and-african-hero-and-martyr/ (accessed on 06.03.2018); “Ruben Um Nyobé immortalisé: Un monument à sa mémoire”. In: Made in Mboa, 13 September 2016. Online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20170424050456/http://madeinmboa.net/ruben-um-nyobe-immortalise-monument-a-memoire/ (accessed on 27.06.2024); “Il paraît qu’une stèle à l’image du nationaliste camerounais Ruben Um Nyobe sera bientôt érigée dans la ville de Douala”. In: Stop Blabla Cam, 2017. Online at: https://www.stopblablacam.com/culture-et-societe/1907-862-il-parait-qu-une-stele-a-l-image-du-nationaliste-camerounais-ruben-um-nyobe-sera-bientot-erigee-dans-la-ville-de-douala (accessed on 06.03.2018); “Cameroun: Ruben Um Nyobé aura son monument à Douala”. In: Actu Cameroun, 19 July 2017. Online at: https://actucameroun.com/2017/07/19/cameroun-ruben-um-nyobe-aura-son-monument-a-douala/ (accessed on 06.03.2018).

3.2. Martyrs

People who were killed in the struggle for independence and subsequently declared martyrs of the nation played an important role in the heroization narratives of decolonised states. These figures were immune to attempts at demystifying them. Simultaneously, their ⟶deaths were so recent at the time of independence that the population could easily relate to their actions. This relationship was maintained over the years through ritualised commemoration. For instance, Aung San (1915–1947) was revered as the father of modern Burma/Myanmar and the day of his assassination was declared a national holiday: “Martyrs’ Day”. The military junta which came to power in 1988 tried to erase him from national heroic memory in order to undermine the legitimacy of his daughter, who opposed the junta. However, his status as a national hero was so deeply ingrained that these efforts were futile.29Cf. Salem-Gervais, Nicolas / Metro, Rosalie: “A Textbook Case of Nation-Building. The Evolution of History Curricula in Myanmar”. In: Journal of Burma Studies 16.1 (2012), 27-78; Morris, Ben: “Leaving Burma Behind”. In: History Today 48.1 (2008), 51-53; “Myanmar Remembers Independence Hero on Martyr’s Day”. In: VOA News, 19 July 2015. Online at: https://www.voanews.com/a/reu-myanmar-remembers-independence-hero-on-martyrs-day/2869301.html (accessed on 06.03.2018).

To the state of Mozambique, Eduardo Mondlane (1920–1969), the leader of the FRELIMO freedom movement, was of similar importance as Aung San was to Myanmar. Mondlane fell victim to a letter bomb in 1969. In 1975, Portugal granted Mozambique independence, and in the same year, the University of Maputo was named after Mondlane.30Cf. Melady / Melady: Ten African Heroes, 2011, 105-119. As with Aung San, numerous streets and monuments, as well as a national holiday, were dedicated to him.31Cf. “Mozambique Honours Nationalist Hero Eduardo Mondlane”. In: Panapress, 3 February 2007.

Some states cultivate a collective ⟶martyrdom that includes not only active independence fighters but also murdered civilians. In São Tomé and Príncipe, the cruel Batepá massacre, in which hundreds of Creole islanders were slaughtered by the Portuguese governor in February 1953, was an important catalyst for the emergence of a national movement. Since independence in 1975, there has been a ritualised commemoration, including a public holiday, a museum, a monument, processions, commemorative events and street names. In public memory, this has led to a reimagining of the massacre as a war of liberation, with the murdered civilians becoming anti-colonial resistance fighters.32Seibert, Gerhard: “Le massacre de février 1953 à São Tomé. Raison d’être du nationalisme santoméen”. In: Lusotopie 1997, 173-192, 187-189 Malawi also has a similar martyr’s day with an explicit reference to the struggle for independence, cf. Manda, Lewi: “Why Kamuzu Chose 3rd March as Martyrs’ Day in Malawi”. In: The Nation, 3 March 2018. Online at: http://mwnation.com/kamuzu-chose-3rd-march-martyrs-day-malawi/ (accessed on 06.03.2018).

3.3. Proto-freedom fighters

The process of inventing a nation usually involves projecting an idea back into history. It was logical to also project the idea of national struggle back to the beginnings of the colonial era and to identify heroes of national resistance who existed at this early stage. This required appropriating and reinterpreting the history of these figures, to whom the concept of the nation had generally been alien.

For instance, Algerian hero Abd al-Qadir, who was to become a symbol of the Algerian nation’s desire for freedom after independence, had actually declared his submission to the French king upon his capture by France and subsequently received a French pension in Ottoman exile. He was thus celebrated by the French colonial rulers as a symbol of Algerian-French reconciliation. Of course, this ambivalence was later ignored by the Algerian independence fighters who, several decades after his death, built him up as the first national freedom fighter.33Cf. Jansen: “Creating National Heroes”, 2016. A similar situation occurred with the memory of Muhammad Ahmad (1844–1885), the Mahdi of Sudan. Although he primarily saw himself as a religious reformer, he was stylised in the 20th century in a rather ahistorical manner as the “father of independence” – an attribution possible only when consistently ignoring his controversial religious message as well as his vehement advocacy of the slave trade.34Cf. Holt, P.M.: “Sudanese Nationalism and Self-Determination, Part I”. In: Middle East Journal 10.3 (1956), 239-147; Voll, John: “The Sudanese Mahdi. Frontier Fundamentalist”. In: International Journal of Middle East Studies 10.2 (1979), 145-166; Warburg, Gabriel R.: “From Sufism to Fundamentalism. The Mahdiyya and the Wahhabiyya”. In: Middle Eastern Studies 45.4 (2009), 661-672. Likewise, it is highly unlikely that Yon Gato, the blind planter who led a troop of slaves to attack a Portuguese landowner on São Tomé in 1553 and is celebrated today as a national hero for this deed, had aspirations for an independent nation state.35Cf. Abreu de Castaño, Inês Filipa: São Tomé e Príncipe: Cultura(s)/Património(s)/Museu(s). MA-Arbeit, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, September 2012, Vol. 1, 31. Online at: https://run.unl.pt/handle/10362/9288 (accessed on 05.03.2018).

Apart from the question of historicity, the appropriation of pre-national heroic figures for nationalist narratives may pose further problems. This is evident in Indonesia, where the ranks of official “National Heroes” include figures from the 19th century, such as the Acehnese women Cut Nyak Dhien (1848–1908) and Cut Nyak Meutia (1870–1910). (Cf. fig. 8.) During the orde baru-era under President Suharto (1966–1988), these local female independence fighters, to whom the idea of an Indonesian nation was still alien, were posted as symbols of that very nation. Given the aspirations of many regions, including Aceh, for greater autonomy or even secession, this was an ambivalent strategy.36Cf. Bijl, Paul: “Colonial Memory and Forgetting in the Netherlands and Indonesia”. In: Journal of Genocide Research 14.3–4 (2012), 441-461.

It is not so much the actual historical agenda of these figures that enables their later appropriation and heroization, but rather the enemy against whom they fought. If the enemy was, in a broad sense, the same colonial power against which an independence movement was formed generations later, then this overlap made it possible to include, in the topography of national heroes, people who had initially fought for their faith, a dynasty, a small region, their own political power or better treatment and remuneration from a landowner. By popularising them, however, they became subject to potential appropriation by competing factions for their respective narratives.

3.4. Mythological heroes

Turning to mythological heroic figures from regional history offered a way of creating a national symbolism without directly referencing colonial history or the nation-building process. This approach was particularly advantageous in cases in which direct references would have been divisive rather than unifying due to the involvement from competing factions in the independence struggle, or when the main protagonists of that struggle were unsuitable for later regime narratives of heroization.

In Burma/Myanmar, for example, the military junta that ruled from 1988 onwards made intensive efforts to promote the veneration of historical kings from the 11th, 16th and 18th centuries as national heroes. The memory of a golden age was intended to overshadow the recent socialist past and also contributed to displacing the (now) problematic national hero Aung San.37Cf. Salem-Gervais / Metro: “A Textbook Case of Nation-Building”, 2008.

In Malaysia, independence was achieved through negotiation. The negotiator, who was later to become the country’s first Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman (1903–1990), was a British-educated lawyer who had worked for the British colonial administration. Although there were violent protests against British rule, the organisers were often marginalised or classified as communist terrorists in post-independence national memory because of their affiliation with trade unions or socialist leanings and their social distance from the political elites.38Cf. Aljunied, Khairudin: Radicals. Resistance and Protest in Colonial Malaya. DeKalb 2015: Northern Illinois University Press. Tunku’s biography itself did not lend itself to heroization, although some official and officious historiographers made attempts to achieve it (cf. source 2).

“Our first Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman held true to our prophetic tradition of the pen being mightier than the sword. He resorted to the negotiation table, not the battlefield, and enlisted lawyers not soldiers in our struggle for independence. Honouring fallen heroes of such wars as martyrs, national heroes, or freedom fighters does not in any way lessen the pain their loved ones endure. We owe Tunku a massive debt of gratitude for sparing us such misfortune. He was truly the quiet and unsung hero of our independence.

This fact needs emphasizing, lest we forget. Already there are “revisionist” historians and other commentators intimating that such an honour belongs to the likes of some obscure failed politicians or former thugs and terrorists. To me, the true hero is not the dashing rescuer who saved the drowning damsel, rather the young boy who kept his finger in the dike and thus prevented a flood.

Tunku went further. Whereas India and Indonesia degenerated into anarchy, Malaysia enjoyed a decade of peace and prosperity following independence.”

Source: Musa, M. Bakri: Moving Malaysia Forward. Bloomington 2008: iUniverse, 13.

Much more than any living politician, however, the five heroes of the Malay folk tale Hikayat Hang Tuah experienced a boom in the 20th century. The story of Hang Tuah and his companions Hang Jebat, Hang Kasturi, Hang Lekir and Hang Lekiu, set in the 15th century Sultanate of Malacca, was first published in print in 1908. It revolves around the bond between Hang Tuah, his closest friend Hang Jebat, and the Sultan, who unjustly sentences Hang Tuah to death. The latter is secretly saved by the executioner. Hang Jebat reacts to the false news of Hang Tuah’s death with rebellion. Upon learning of Hang Tuah’s innocence, the Sultan pardons him and tasks him with quelling Hang Jebat’s rebellion. Following an epic battle, Hang Tuah defeats Hang Jebat.39Cf. De Jong, P.E. de Josselin: “The Rise and Decline of a National Hero”. In: Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 38.2 (1965), 140-155; Nanney, Nancy K.: “Evolution of a Hero. The Hang Tuah/Hang Jebat Tale in Malay Drama”. In: Asian Theatre Journal 5.2 (1988), 164-174.

From the 1930s onwards, the story became the subject of numerous popular ⟶dramas in Malaya. In 1956, a Malaysian-produced film about Hang Tuah caused great excitement. The drama of Hang Tuah was extensively utilised to navigate the political landscape during the nation-building process; to varying extents, either Hang Tuah, characterised by unwavering loyalty to the ruler, or his friend and later antagonist Hang Jebat, who is committed only to his own conscience, were framed as the main heroic character.

The popularity of the epic was increasingly reflected in official symbolism after Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad (1981–2003) took office. He initiated the renaming of streets in Kuala Lumpur on a grand scale. In 1982, Rodger Street, named after a British representative, became Jalan Hang Kasturi, and Davidson Road, named after another British representative, became Jalan Hang Jebat. The other three heroes from the Malay folk epic also lent their names to streets in downtown Kuala Lumpur, replacing European names that commemorated the colonial era.40Cf. Tye, Timothy: “Jalan Hang Kasturi”; “Jalan Hang Jebat”; “Jalan Hang Lekiu”; “Jalan Hang Lekir”; “Jalan Hang Tuah”. In: Timothy Tye Everywhere. Online at: http://www.timothytye.com/asia/malaysia/kuala-lumpur/jalan-hang-kasturi.htm; http://www.timothytye.com/asia/malaysia/kuala-lumpur/jalan-hang-jebat.htm; http://www.timothytye.com/asia/malaysia/kuala-lumpur/jalan-hang-lekiu.htm; http://www.timothytye.com/asia/malaysia/kuala-lumpur/jalan-hang-lekir.htm; http://www.timothytye.com/asia/malaysia/kuala-lumpur/jalan-hang-tuah.htm (accessed on 05.03.2018). This initiative was directly related to Mahathir’s commitment to the urban development of Kuala Lumpur and to his programme of indigenous modernisation. Moreover, it underscored the policy of promoting the bumiputra – the population groups that, in contrast to Indians and the Chinese, were classified as autochthonous – which had been effective since 1969. The reference to the heroic epic of Hang Tuah aptly framed national identity as predominantly Malay.41Cf. Wain, Barry: Malaysian Maverick. Mahathir Mohamad in Turbulent Times. Basingstoke 2009: Palgrave Macmillan, 53-123.

Historical hero myths can thus be employed to shape and consolidate a national identity that is not exclusively defined by individual figures active in the independence movement and representatives of the postcolonial political system, even though they still potentially exclude certain groups. At the same time, these heroic myths can provide a framework for navigating the political upheavals of decolonisation, being adapted and reinterpreted according to the changing needs of the time.

4. Structural issues

4.1. Official and private commemoration of heroes

4.1.1. State cults of heroes

The governments of the newly independent nation states were the primary agents of heroization in the course of decolonisation. This was logical, as many of these nation states, like their colonial predecessors, claimed exclusive control of public spaces, education and the calendar. Monuments, names of streets and institutions, school textbooks, and state holidays as central ⟶media of hero worship were primarily overseen by the ruling regimes. Some regimes also controlled the media and parts of the art and culture scene and used them for their heroization campaigns. ⟶Heroic commemoration is inscribed in the structure of many postcolonial states, both in time and in space, shaping their narratives.

A number of countries observe a “Heroes’ Day” as a public holiday in commemoration of the struggle for independence. The day sometimes commemorates a specific hero, as Agostinho Neto (1922–1979) in Angola, Amílcar Cabral (1924–1973) in Cape Verde, and Eduardo Mondlane in Mozambique. In other cases, it collectively honours all those involved in the struggle for independence, as seen in Indonesia, Kenya, Namibia or Zimbabwe.42Cf. “Angola Pays Tributes on Day of the National Hero”. In: Holidays around the World, n.d.; “Cabral remembered on National Heroes Day”. In: ASemana, 20 January 2012; Bogaerts, Els: “‘Wither Indonesian Culture?’ Rethinking ‘Culture’ in Indonesia in a Time of Decolonisation”. In: Lindsay, Jennifer / Liem, Maya H.T. (Eds.): Heirs to World Culture. Being Indonesian 1950–1965. Leiden 2012: KITLV Press, 223-254, 226; “It is Time for Kenyans to Stop Celebrating Madaraka Day”. In: The Conversation, 31 May 2017. Online at: https://theconversation.com/it-is-time-for-kenyans-to-stop-celebrating-madaraka-day-78608 (accessed on 07.03.2018); “Celebrating the Heroes of Namibia”. In: Namibia. Endless Horizons. Online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20181230143610/http://www.namibiatourism.com.na/blog/Celebrating-the-Heroes-of-Namibia (accessed on 27.06.2024); “‘Heroes Day Not Just a Holiday, it Means a Lot’”. In: The Herald, 12 August 2017. Online at: https://www.herald.co.zw/heroes-day-not-just-a-holiday-it-means-a-lot/ (accessed on 07.03.2018).

Among the most emblematic postcolonial hero memorials are the Heroes’ Acres in Zimbabwe and Namibia (cf. figs. 9-10). Both sites aspire to commemorate the heroes of the anti-colonial liberation struggle through a large ensemble of gravestones, statues, mausoleums, museums, monuments, parade grounds and murals. The intention was to create a pantheon of national heroes, which was later supplemented with figures from the nation state’s history. However, both projects were also subject to criticism for serving primarily as regime propaganda. Designed by North Korean architects and built by North Korean construction companies, theses large-scale government projects have been attacked for their limited involvement of local cultural representatives or civil society. Critics argue that they only include figures closely aligned with the ruling party, while many far more deserving heroes are excluded due to their lack of connection to the political elite.43Cf. Mpofu, Shepherd: “Participation, Citizen Journalism and the Contestations of Identity and National Symbols. A Case of Zimbabwe’s National Heroes and the Heroes’ Acre”. In: African Journalism Studies 37.3 (2016), 85-106; Becker, Heike: “Commemorating Heroes in Windhoek and Eenhana. Memory, Culture and Nationalism in Namibia, 1990–2010”. In: Africa 81.4 (2011): 519-543; see also Malaba, Sakhile: “Mugabe Says National Heroes Acre is Solely for Zanu PF Members”. In: Metro Zimbabwe, 1 October 2010. Online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20110626075612/http://www.zimbabwemetro.com/opinion/mugabe-says-national-heroes-acre-is-solely-for-zanu-pf-members/ (accessed on 07.03.2018).

The case of Indonesia shows the many ways in which post-colonial states may engage in a ritualised cult of heroes. The government posthumously awards the title of “National Hero”, creating an ever-growing list of figures who fought against the Netherlands in the 19th and 20th centuries. These heroes are honoured through monuments, banknotes, schoolbooks, biographies and films. Various heroes’ cemeteries and rituals of hero worship, such as ritual burials and reburials, are intended to ensure their place in national memory.44Cf. Schreiner, Klaus H.: “‘National Ancestors’. The Ritual Construction of Nationhood”. In: Chambert-Loir, Henri/ Reid, Anthony (Eds.): The Potent Dead. Ancestors, Saints and Heroes in Contemporary Indonesia. Crows Nest und Honolulu 2002: Allen & Unwin / University of Hawai’i Press, 183-204. Similar to Benedict Anderson’s description of the inflation of national monuments after independence, nationalist and autocratic regimes that introduced these hero commemoration practices were not interested in a sincere engagement with history but rather in creating icons and appropriating them for a national project.45Cf. Schreiner, Klaus: “The Making of National Heroes. Guided Democracy to New Order”. In: Schulte Nordholt, Henk (Ed.): Outward Appearance. Dressing State and Society in Indonesia. Leiden 1997: KITLV Press, 259-290; Anderson, Benedict O.G.: Language and Power. Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia. Jakarta 2006: Equinox Indonesia (Reprint of the original edition Ithaca 1990: Cornell University Press), 173-183.

This type of state control of heroization discourses leaves no room for local, individual forms of remembrance.46Cf. Bijl: “Colonial Memory and Forgetting”, 2012, 452-458. Counter-narratives often run the risk of being branded as political dissidence (cf. source 3).

“[…] how did Kenyatta stand out as one in whom the nation would invest its memory of colonial counterinsurgency? How would the independence struggle be reduced to Kenyatta’s trial and incarceration? How come Kenyatta would be the one through whom known and unknown other “heroes” would have to be remembered in the nation’s collective memory? […] Knowingly or unknowingly, Kenyatta Day as a day of remembrance elevated Kenyatta above the status of “just a hero” so he was the hero. […] There was no room for other heroes who would diminish the potency of Kenyatta’s heroic memory. […] Kenyatta’s own name on buildings, streets, sports stadiums, schools, airports, and so on would suffuse the national memorial and architectural landscape without parallel. The biggest and best spots were reserved for him: Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, Nairobi; Kenyatta International Conference Center, Nairobi; Kenyatta Avenue, Nairobi; Kenyatta Avenue, Mombasa; and Kenyatta Street, Kitale; Kenyatta National Hospital, Kenyatta University College, Kenyatta Stadium, Machakos; Kenyatta Stadium, Kisumu; Kenyatta Stadium, Kitale, and so on. […] The hero worship of Kenyatta was what the government wanted inculcated in the minds of the generation then and in the generations after. It was reflected in the patriotic songs that artists composed in the scramble to outdo one another in their apotheosizing of the singularity of Kenyatta’s remembrance and memorialization. Doubts were cast upon your patriotism, if you did not sing songs in praise of the Baba wa Taifa.

But always concurrent with and in conflict with this pervasive state-instigated collective memory of Kenyatta as hero and saint was another narrative that fed on bitter individual and collective experiences. We shall call this the unofficial and unauthorized collective memory, whose perpetuation was the task-narrative of so-called dissidents.”

Source: Waliaula, Ken Walibora: The Thoughful Museum. Remembering and Disremembering in Africa. In: Curator. The Museum Journal 55,2 (2012), 113-127, 119-121.

4.1.2. Counter-narratives, privatisation and diversification

In many cases, the success of state-imposed hero worship has proven to have its limits. In Myanmar, for example, the military junta did not succeed in erasing Aung San’s heroization from public memory after taking power; instead, the regime had to come to terms with it.47Cf. Salem-Gervais / Metro: “A Textbook Case of Nation-Building”, 2008. Often, parts of the population look through the government’s strategy of exclusively focussing hero memorisation on a specific political faction while completely supressing the memory of other actors, and to the extent that the political field and media landscape allow for it, this strategy is questioned. This is evident in the debates about the Heroes’ Acres or attempts to commemorate leftist Malaysian resistance fighters.48Cf. Goredema, Dorothy / Chigora, Percyslage: “Fake heroines and the falsification of history in Zimbabwe 1980–2009”. In: African Journal of History and Culture 1.5 (2009), 76-83; Yusop, Al-Jafree Md / Zahar, Syed: “The Original Heroes of Merdeka”. In: Malaysian Digest, 25 August 2011. This type of contestation may be carried out openly by political opposition groups or in private contexts, such as through the cultivation of family memories.

The case of Vietnam is particularly instructive. After 1975, the communist government monopolised heroic commemoration, covering the period from the declaration of independence in 1945 to the end of the Vietnam War. The government strictly distinguished between ‘revolutionary martyrs’ and those deceased or fallen who did not deserve this status – either because they belonged to the troops of the South Vietnamese ‘puppet regime’, died in a battle against an ideologically similar enemy (particularly China), because their loyalty to the communist cause was in doubt, or their deaths were not considered sufficiently heroic (see ⟶death and dying). For the ‘revolutionary martyrs’ there is a highly ritualised cult of hero worship involving heroes’ cemeteries and commemorative ceremonies. These practices are designed to suppress the memory of ideologically unsuitable fighters, even resorting to fabrications (cf. source 4).

“In 1983, […] by decision of the Hồ Chí Minh City administration, the Mạc Đĩnh Chi Cemetery, where many leading politicians, military officers and other personalities of the Republic of Vietnam were buried, was rased to the ground. Lê Văn Tám Park was built on the site – named after a 14-year-old revolutionary ‘martyr’ from the war against the French who allegedly doused himself with petrol and set himself on fire in 1946 to blow up a French petrol depot as a ‘living torch’. It is an irony of history that this new memorial site, dedicated entirely to the socialist revolutionary cult of the victors, stands on feet of clay: the ‘martyr’ Lê Văn Tám, after whom many schools, streets, cinemas and parks in Vietnam are named, was purely an invention of the former propaganda minister Trần Huy Liệu.”

(“1983 wurde […] auf Beschluss der Stadtverwaltung von Hồ Chí Minh-Stadt der Mạc Đĩnh Chi-Friedhof, auf dem viele führende Politiker, Militärs und andere Persönlichkeiten der Republik Vietnam beerdigt waren, dem Erdboden gleichgemacht. Auf dem Gelände wurde der Lê Văn Tám-Park errichtet – benannt nach einem 14-jährigen revolutionären ‘Märtyrer’ aus dem Krieg gegen die Franzosen, der sich 1946 angeblich mit Benzin übergossen und angezündet hatte, um als ‘lebende Fackel’ ein französisches Benzindepot in die Luft zu sprengen. Es ist eine Ironie der Geschichte, dass diese neue Gedenkstätte, die ganz dem sozialistischen Revolutionskult der Sieger verpflichtet war, auf tönernen Füßen steht: der “Märtyrer” Lê Văn Tám, nach dem viele Schulen, Straßen, Kinos und Parks in Vietnam benannt sind, war eine reine Erfindung des früheren Propagandaministers Trần Huy Liệu.”)

Source: Großheim, Martin: “Der Krieg und der Tod. Heldengedenken in Vietnam”. In: Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 65.4 (2017), 545-581, 563.

With the expansion of the space for individual expression from the 1990s onwards, a trend towards disengagement from state-ordained hero commemoration and the privatisation of personal remembrance has become noticeable. Consequently, religious ceremonies honouring ancestor saw a resurgence in private settings, and non-governmental organisations, such as veterans’ associations and associations of Vietnamese abroad, initiated commemorative activities focusing on gaps in state commemoration. Particularly with regard to the Vietnamese who died in battles against China, there has emerged a vibrant private culture of remembrance, which also leads to demands on the state for revising the politics of the commemoration of heroes.49Cf. Großheim Martin: “Der Krieg und der Tod. Heldengedenken in Vietnam”. In: Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 65.4 (2017), 545-581.

Official and private forms of commemoration intersect in the adoration of state-heroized personalities, first and foremost Ho Chi Minh, who has become the subject of religious rituals contrary to state directives. This heroization has led to a politically unintended deification.50Cf. Lauser, Andrea: “Zwischen Heldenverehrung und Geisterkult. Politik und Religion im gegenwärtigen spätkommunistischen Vietnam”. In: Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 133.1 (2008), 121-144.

4.2. Global heroes

Although decolonisation and the heroization strategies that emerged from it were predominantly tied to the formation of nation-states with strong nationalist overtones, they also had transnational and global dimensions. These could arise from the newly emerging South-South relations, evident in the movement of non-aligned states, and from shared struggles against the same colonial power. One such example is the British officer Charles George Gordon, who participated in the conquest of Beijing in the Second Opium War and was killed by the Mahdists in Sudan in 1885, thereby linking China and Sudan. Chinese Premier Zhou En Lai, during his visit to Khartoum in 1964, reportedly thanked the Sudanese people for bringing Gordon to justice and avenging China.51Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation-Building?”, 2014, 941; Large, Daniel / Patey, Luke: “Sudan ‘Looks East’”. In: Large, Daniel / Patey, Luke (Eds.): China, India and the Politics of Asian Alternatives. Woodbridge 2011: James Currey, 1-34, 5.

In the 1950s and 1960s, an influential global anti-colonial discourse emerged that was framed in extremely heroic terms. Decolonisation was portrayed as a global struggle by the oppressed for their freedom. This allowed heroization narratives to transcend borders. Thus, Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam called the Algerian freedom fighter Abd al-Qadir a national hero and champion of the people’s war in Vietnam, and Che Guevara proclaimed at the Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference in 1968:

“Here and at all conferences, wherever they may be held, we should – along with our greeting to the heroic peoples of Vietnam, Laos, ‘Portuguese’ Guinea, South Africa, or Palestine – extend to all exploited countries struggling for emancipation our friendly voice, our hand, and our encouragement; to our brothers in Venezuela, Guatemala, Colombia who, having taken up arms today, are saying a final ‘No!’ to the imperialist enemy.”52Khalili, Laleh: Heroes and Martyrs of Palestine. The Politics of National Commemoration, Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press, 16.

The global dimension of the production of anti-colonial liberation heroes was intricately intertwined with the context of the Cold War and the convergence of socialist and communist states both within the Eastern Bloc and the Non-Aligned Movement. This is not to say that all of the communist resistance fighters who successfully fought against a colonial power and later assumed leadership were equally internationally oriented. Perhaps the most prominent counter-example is the North Korean partisan leader and subsequent dictator Kim Il Sung (1912–1994), whose legitimacy stemmed from the struggle against Japanese colonial rule. As head of state, he pursued a policy of isolation and self-sufficiency, while concurrently fostering an intense personality cult that focused all of North Korea’s heroization narratives on his persona (cf. source 5).

The Song of General Kim Il Sung

1. Bright traces of blood on the crags of Changbaek still gleam,

Still the Amnok carries along signs of blood in its stream,

Still do those hallowed traces shine respendently,

Over Korea ever flourishing and free.

So dear to all our hearts is our General’s glorious name,

Our own beloved Kim Il Sung of undying fame.

2. Tell, the blizzards that rage in the wild Manchurian plains,

Tell, you nights in forests deep where the silence reigns,

Who is the partisan whose deeds are unsurpassed?

Who is the patriot whose fame shall ever last?

So dear to all our hearts is our General’s glorious name,

Our own beloved Kim Il Sung of undying fame.

3. He severed the chains of the masses, brought them liberty,

The sun of Korea today, democratic and free.

For the Twenty Points united we stand fast,

Over our fair homeland spring has come at last!

So dear to all our hearts is our General’s glorious name,

Our own beloved Kim Il Sung of undying fame.

Source: https://web.archive.org/web/20070930055535/http:/www.kcckp.net/images/periodic/todaykorea/2007/04/e-0.jpg (accessed on 24.06.2024).

The situation was completely different for Che Guevara (1928–1967), the Cuban revolutionary (who was actually Argentinian), who continued his struggle for world revolution in the Congo and Bolivia and became a global icon. In the Socialist International, the notion of revolutionary struggle for the interests of the oppressed was the link that allowed for identification with heroes across national borders. European socialist states therefore pursued the heroization of anti-colonial freedom fighters in art, literature and state media, often while simultaneously repressing their own colonising past. In Hungary, for example, the heroic examples of Vietnam and, initially, the heroes of the Cuban Revolution were enthusiastically celebrated and linked to the country’s own history, specifically the revolution of 1848: “Che Guevara was a modern-day reincarnation of Hungarian romantic hero-martyr Sándor Petőfi.”53Cf. Mark, James / Apor, Péter: “Socialism goes Global. Decolonisation and the Making of a New Culture of Internationalism in Socialist Hungary, 1956–1989”. In: The Journal of Modern History 87 (2015): 852-891, 864. During the 1960s, however, as Hungarian socialism consolidated and became more bureaucratic, it seemed increasingly necessary to downplay the appeal of the romantic revolutionary hero Che Guevara. Military daring, ⟶heroic deeds and revolutionary drive were now considered undesirable; Che Guevara became a symbol of irresponsibility. In 1970, the Hungarian Minister of Culture declared that, while Guevara was indeed a hero who had made the impossible possible, he could have been an even greater hero if he had dedicated himself to the tedious work of socialist construction, as Lenin, for example, had done.54Cf. Mark / Apor: “Socialism goes Global”, 2015, 880. In this regard, Ho Chi Minh was less problematic and therefore easier to establish as an international socialist hero, but unlike Che Guevara, he did not become a pop culture icon on the long term.

4.3. Violence

The predominantly violent nature of the decolonisation process has significantly influenced the emergence of heroic figures, as well as the strategies used to heroize them. Fighters were the main object of heroization projects, alongside the ⟶violence they perpetrated, which was justified by the aggression emanating from the militarily superior colonial powers. The wars of independence were characterised by an asymmetry of forces that facilitated heroizations: achieving independence appeared as a victory against an overwhelmingly stronger opponent, even if independence itself rarely resulted directly from military victory. Consequently, martial forms of hero worship and hero commemoration prevailed, often combined with a prominent role for the military in the independent nation states.

This tendency towards martial heroism was reflected not only in the selection of heroic figures, but also in the narratives and iconographies of heroization. The Kalashnikov as a typical guerrilla weapon repeatedly appears in heroic representations. For instance, the Heroes’ Acre in Namibia features a six-metre-high statue of a fighter poised to throw a hand grenade with his right hand, while holding a Kalashnikov in his left (cf. fig. 11).55Cf. Becker: “Commemorating Heroes in Windhoek and Eenhana”, 2012, 525. Similarly, the Heroes’ Acre in Zimbabwe is entirely constructed in the form of two Kalashnikov rifles with the heroes’ graves symbolising the magazines.56Cf. Mpofu: “Participation, Citizen Journalism and the Contestations of Identity and National Symbols”, 2016, 66. This martial cult of heroes demonstrates a high degree of persistence. Thus, the processes of privatisation and diversification of heroic commemoration in Vietnam have not led to a rejection of martial heroism, but rather included previously marginalised groups within the category of heroic fighters.57Cf. Großheim: “Der Krieg und der Tod”, 2017, 578.

There are certainly deviations from the model of the martial freedom fighter, for example in states such as Tunisia and Malaysia, where independence was primarily achieved through negotiation. Interesting in this context is the statue of Ruben Um Nyobé holding a briefcase, which shows him returning to his hometown from a UN summit (cf. fig. 7). In this case, his presence on the international stage contributes to his heroization.

The most prominent case in which the explicit rejection of violence was a central element to the creation of a hero is that of Gandhi (1869–1948), the Indian national hero. It is probably no coincidence that he is an exception to Benedict Anderson’s observation that the pioneers of the last wave of nation building were almost exclusively young men.58Cf. Anderson: “Die Erfindung der Nation”, 1998, 105. Gandhi, conversely, was in his late seventies at the time of India’s independence. Gandhi’s status as an icon of non-violence may also have served to push the very bloody course of India’s partition following independence into the background in national memory. In Indian and international perception, the memory of Ghandi often covers a much more complex history of nation-building, in which numerous actors, both violent and non-violent, played a role and radical, violence-affirming political philosophies emerged alongside Gandhi’s programme of non-violence.59Cf. Kapila, Shruti: “A History of Violence”. In: Modern Intellectual History 7.2 (2010), 437-457. Between war and non-violence existed a broad field of action ranging from strikes, blockades and acts of civil disobedience to acts of sabotage and assassinations. The focus of national memory on Gandhi reproduced his view of more militant independence fighters such as Bhagat Singh (1907–1931) as terrorists, which was consistent with British perceptions.60Cf. Nair, Neeti: “Bhagat Singh as ‘Satyagrahi’. The Limits to Non-violence in Late Colonial India”. In: Modern Asian Studies 43.3 (2009), 649-681. The question of whether Bhagat Singh was the greater hero and whether Gandhi was partly to blame for his death remains contested in India today and is linked to different communal and religious perspectives.

Questions regarding the legitimacy of violence, however, do not appear to factor into the general view on the Indian uprising of 1857, possibly due to the temporal distance. The successful Indian film The Rising (2005) heroizes the uprising’s initiator Mangal Pandey (1831–1857) as the “first independence fighter” and martyr, thus embracing a common narrative. The film credits introduce the story as follows:

“The man who changed history

his courage inspired a nation

his sacrifice gave birth to a dream

his name will forever stand for FREEDOM.”61Erll, Astrid: “Remembering across Time, Space, and Cultures. Premediation, Remediation and the ‘Indian Mutiny’”. In: Erll, Astrid / Rigney, Ann (Eds.): Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory. Berlin 2009: De Gruyter, 109-138, 129.

The film portrays the years 1857 and 1947 as memory sites that are closely linked in Indian history; the images in the end credits connect the mutinous soldier Mangal Pandey with the protest marches organised by Gandhi. The motif of the freedom struggle pushes the dichotomy of violence and non-violence into the background.62Cf. Erll: “Remembering across Time”, 2009, 128-131.

4.4. Gender

The very small number of heroines is among the conspicuous consequences of the dominance of the masculine archetype of the martial freedom fighter among the heroes of decolonisation.63Cf. Carrier, Neil / Nyamweru, Celia: “Reinventing Africa’s National Heroes. The Case of Mekatilili, a Kenyan Popular Heroine”. In: African Affairs 115 (2016), 599-620, 600. The monopolisation of hero worship by the political elites of the independent states, among whom there were also hardly any women, exacerbated this situation. Exceptions to this norm, whether in terms of state leadership or hero status, often involved wives, widows, or daughters of renowned male freedom fighters. In 2015, for example, among 110 national heroes buried on Zimbabwe’s Heroes’ Acre, only six were women, mostly wives of prominent members of Mugabe’s ZANU PF. Many women indeed played crucial roles in the struggle for independence; their absence from official hero commemoration stemmed from their lack of relevant family connections.64Cf. Goredema/ Chigora: “Fake heroines”, 2009; Marongwe, Ngonidzashe / Mgadzike, Blessed: “The Challenges of Honouring Female Liberation War Icons in Zimbabwe. Some Discourses about the National Heroes Acre”. In: Mawere, Munyaradzi / Mubaya, Tapuwa R. (Eds.): Colonial Heritage, Memory and Sustainability in Africa. Challenges, Opportunities and Prospects. Bamenda 2016: Langaa, 139-168.

Insofar as a certain symbolic representation of women was sought within the pantheon of heroes, it mostly corresponded to the masculine-martial hero type. For instance, the monument on the “Tomb of the Unknown Soldier” on Zimbabwe’s Heroes’ Acre depicts two men and a woman. The expression on the woman’s face is fierce and determined, similar to that of the men, and she is also depicted carrying a machine gun (cf. fig. 9). The Indonesian national heroes Cut Nyak Dhien and Cut Nyak Meutia, who in 1964 together with the women’s rights icon Kartini (1879–1904) were the first women to be included in the ranks of national heroes, also belonged – at least in their official representation and public perception – to this type.65Cf. Vredian, Fiqh: “Masculinities and Peacebuilding Agency in Ambon and Aceh”. In: Center for Religious and Cross-Cultural Studies, Graduate School, Universitas Gadjah Mada, 2018. Online at: https://crcs.ugm.ac.id/masculinities-and-peacebuilding-agency-in-ambon-and-aceh/ (accessed on 25.06.2024).

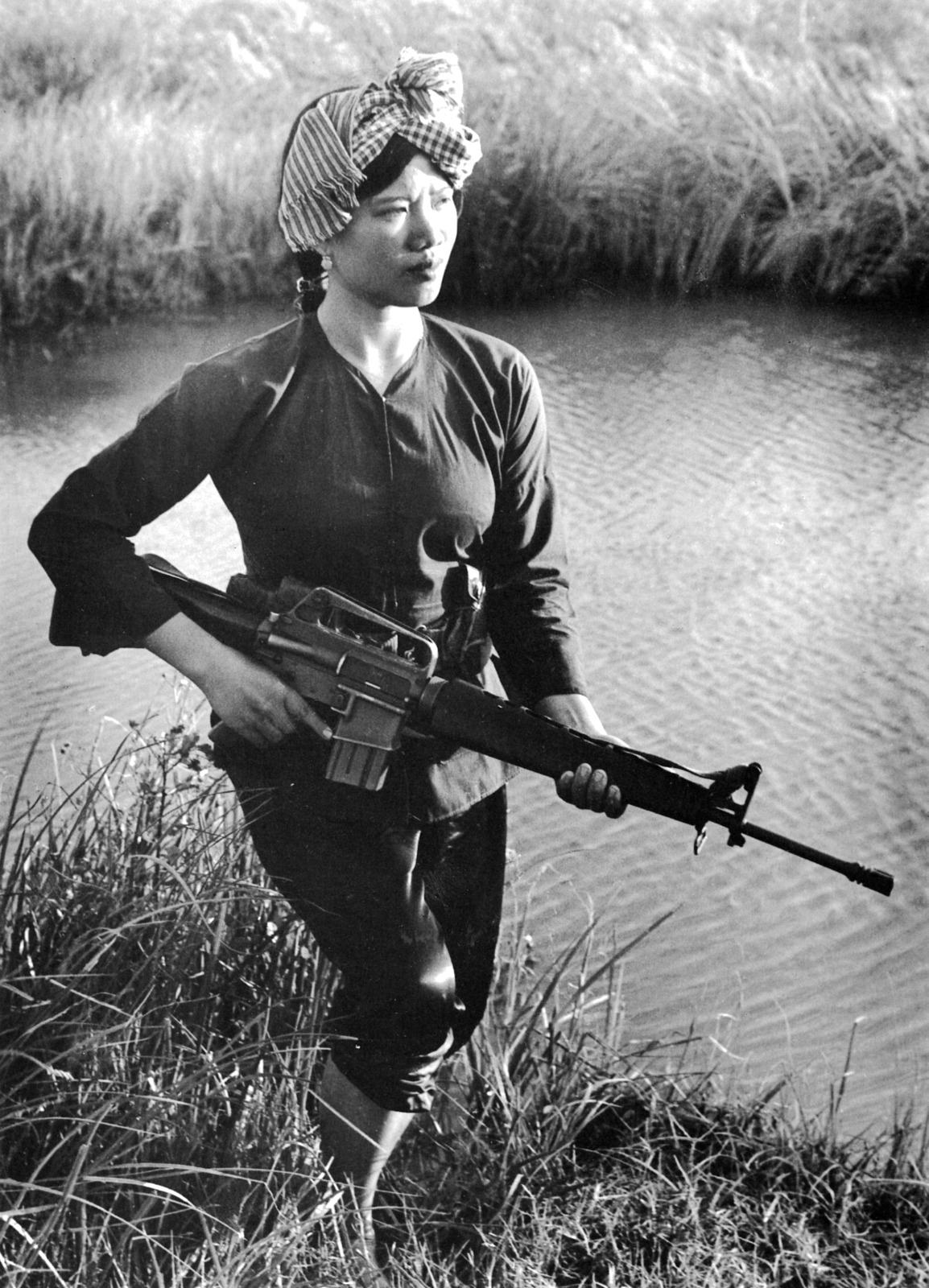

Movements and states with socialist orientations were particularly inclined to assign women a combative role, albeit symbolically. In Vietnam, for example, the hagiographic legend of the Tru’ng sisters was reappraised in the course of the 20th century and reinterpreted as a national myth. The two daughters of a local nobleman from the 1st century AD, who were credited with a righteous but ultimately unsuccessful rebellion against an oppressive Chinese governor, became national heroines during the colonial and post-colonial eras, serving as figures of identification and symbols of a heroic heritage. In the course of the retelling, their rebellion changed from an elite revolt to a mass movement. War was consistently portrayed positively as the only effective form of resistance. However, while pre-colonial depictions tended to interpret the sisters’ gender as a weakness and the reason for their defeat, later accounts increasingly portrayed them as capable patriotic leaders, intended to be role models for Vietnamese women.66Cf. Womack, Sarah: “The Remakings of a Legend. Women and Patriotism in the Hagiography of the Tru’ng Sisters”. In: Crossroads 9.2 (1995), 31-50. Many women fought in the Viet Cong in particular, but also in the South Vietnamese armed forces.67Regarding South Vietnam Cf. Stur, Heather: “South Vietnam’s ‘Daredevil Girls’”. In: New York Times, 1 August 2017. Online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/01/opinion/vietnam-war-girls-women.html (accessed on 08.03.2018). An iconic photograph by North Vietnamese war photographer Le Minh Truong demonstrates the powerful impact of the heroization of female fighters (cf. fig. 13). It depicts a young woman, already twice widowed at the age of 24, standing guard for the Viet Cong. She holds her American rifle ready to fire, her posture and gaze signalling calm determination. Here, youth and femininity serve as a contrasting foil against which the soldier’s fighting courage and her willingness to kill or be killed particularly stand out. Such images were often used for propaganda purposes and staged accordingly. A photo by Lam Hong shows how the victims of an American attack were not only questioned about their experiences in front of Vietnamese and foreign journalists, but also posed for the photographers (cf. fig. 14).

Conversely, in anti-communist Malaysia, female heroism was mainly associated with offering assistance to men. Siti Rahmah Kassim (1926–2017), for example, became famous for spontaneously donating her gold bracelet to Tunku Abdul Rahman to help finance his trip to England so he could negotiate independence with the British. This act reportedly inspired many other Malaysians to donate to this cause as well.68Cf. Chu, Mei Mei: “Siti Rahmah, Unsung Hero in Fight for Merdeka, Dies”. In: The Star Online, 24 March 2017. Online at: https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/03/24/siti-ramah-unsung-hero-in-fight-for-merdeka-dies/ (accessed on 08.03.2018).

In some countries with ritualised adoration of anti-colonial heroes, sensitivity to the limited representation of women in the respective national pantheon of heroes has increased in recent years. In Kenya, for example, a counter-movement emerged to address the strongly masculinised hero culture of the post-colonial era. This re-orientation also gained urgency for the state in the wake of the violent ethnic conflicts of 2008. The masculine, martial, ethnically and ideologically narrow canon of heroes was increasingly seen as divisive. State committees were set up to ensure more diversity; this was accompanied by significant engagement from civil society actors, with the result that the adoration of Jomo Kenyatta (1893–1978) was replaced by that of a broader range of male and female national heroes. For example, the public holiday formerly known as “Kenyatta Day” was renamed “Heroes’ Day (siku ya mashujaa)”. In the new Kenyan pantheon, Mekatilili wa Menza (c. 1840s–c. 1925), who led an uprising against the British in 1913, occupies a central role. In 2010, a statue of her was unveiled in Uhuru Gardens in Nairobi, the central site for commemorating independence, and a festival was initiated in her honour.69A photo of the statue of Mekatililis can be found in Kihuria, Njonjo: “How colonial askaris ‘borrowed’ wives at the Coast”. In: The Star, 21 February 2013. Kenyan women can receive Mekatilili’s name as an honorary title based on special merits. Mekatilili was turned into a national myth, providing a counterpoint to the patriarchs of African and global anti-colonial liberation movements. However, even with this diversification, the hero cult’s martial framing remains.70Cf. Carrier / Nyamweru: “Reinventing Africa’s National Heroes”, 2016; “Mekatilili Takes Place of Honour”. In: Daily Nation, 20 October 2010. Online at: https://www.nation.co.ke/news/politics/1064-1036930-frxcbr/index.html (accessed on 08.03.2018).

5. Research perspectives

Overall, heroization processes resulting from the decolonisation movement are still a relatively young field of research. So far studies primarily examine individual countries and case studies and provide numerous findings that would benefit from being situated in a broader context. Comparative and overarching analyses are sparse and mostly focus on Africa.71Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 2014; Berenson, Heroes of Empire, 2011. There is a significant lack of research on many countries, reflecting inequalities with regard to local research conditions as well as imbalances in regional studies, some of which have identifiable historical reasons while others may be accidental.

An important, yet insufficiently explored field of research concerns the iconography of anti-colonial heroines and heroes in cross-national comparison including also the socialist context. Photography as a medium of heroization in postcolonial contexts has also received little attention to date.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, scholars from numerous postcolonial states have increasingly contributed to the exploration of national cultures of heroization and commemoration within their societies. These contributions have proven to be exceptionally innovative and instructive, particularly when shedding light on the underresearched non-hegemonic cultures of remembrance as well as counter-discourses to state-controlled memorialisation practices.

6. Einzelnachweise

- 1This article is adapted from the 2018 German article ⟶Dekolonisation in Compendium heroicum.

- 2Osterhammel, Jürgen / Jansen, Jan C.: Decolonization. A short history. Transl. by Jeremiah Riemer. Princeton / Oxford 2017: Princeton University Press, 1f.

- 3Cf. Anderson, Benedict: Die Erfindung der Nation. Zur Karriere eines folgenreichen Konzepts. Berlin 1998: Ullstein, 100-121.

- 4Cf. Osterhammel, Jürgen / Jansen, Jan C.: Dekolonisation. Das Ende der Imperien. Munich 2013: C.H. Beck, 9.

- 5Cf. fundamental to this Sèbe, Berny: Heroic Imperialists in Africa. The Promotion of British and French Colonial Heroes, 1870–1939. Manchester 2013: Manchester University Press.

- 6Cf. Malinowski, Stephan: “Modernisierungskriege. Militärische Gewalt und koloniale Modernisierung im Algerienkrieg (1954–1962)”. In: Kruke, Anja (Ed.): Dekolonisation. Prozesse und Verflechtungen 1945–1990. Bonn 2009: Dietz, 213-248.

- 7Cf. Sèbe, Berny: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation-Building? British and French Imperial Heroes in Twenty-First-Century Africa”. In: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42.5 (2014), 936-968, 936.

- 8Cf. Trotman, David V.: “Acts of Possession and Symbolic Decolonisation in Trinidad and Tobago”. In: Caribbean Quarterly 58.1 (2012), 21-43.

- 9Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation-Building?”, 2014, 940-945.

- 10Berenson, Edward: Heroes of Empire. Five Charismatic Men and the Conquest of Africa. Berkeley / Los Angeles 2011: University of California Press, 273.

- 11Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 2014, 945-946.

- 12Cf. Taithe, Bertrand / Davis, Katherine: “‘Heroes of Charity?’ Between Memory and Hagiography: Colonial Medical Heroes in the Era of Decolonisation”. In: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42.5 (2014), 912-935, 923-924.

- 13Cf. Taithe / Davis: “‘Heros of Charity?’” 2014, 924-926.

- 14Cf. Koplik, Mark: “Le Grand Blanc de Lambaréné”. In: Film Notes. Online at: https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst/webpages4/filmnotes/fns98n4.html (accessed on 02.03.2018).

- 15Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 2014, 946-951.

- 16Cf. Berenson: Heroes of Empire, 2011, 275.

- 17Cf. Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 2014, 953-962; Berenson: Heroes of Empire, 2011, 283-285.

- 18Cf. Jorio, Rosa de: “Politics of Remembering and Forgetting. The Struggle over Colonial Monuments in Mali”. In: Africa Today 52.4 (2006), 79-106; Sèbe: “From Post-Colonialism to Cosmopolitan Nation Building?”, 952-953.