- Version 1.0

- published 29 June 2024

Table of content

- 1. Definition and delimination

- 2. The adoption of the Aristotelian term in Christian virtue theory

- 3. Heroic virtue in post-Tridentine canonisation practice

- 4. Saints as the ‘better heroes’ – the Christian surpassing of the classical hero

- 4.1. Saints as caregivers and rescuers of the sick

- 4.2. Saints as converted soldiers

- 4.3. Saints as helpers on the battlefield

- 5. Heroizations in mysticism: martyrdom of the fire of love

- 6. Literature review and perspectives for future research

- 7. References

- 8. Selected literature

- 9. List of images

- Citation

1. Definition and delimination

Heroic virtue (also referred to as heroic virtus or virtus heroica) denotes an eminence of virtue in either quality or quantity which exceeds normal standards. Having it is understood as either sharing in the divine in the sense of a divine gift of grace or as being similar with God or higher beings through the perfection of the virtues. Classing exceptional virtue into the sphere of the divine ⟶sacralises those who have such virtue and secures for them the status of venerable individuals. On the one hand, in its reception throughout history in general, the originally Aristotelian concept gained wide significance not only because heroic virtue was seen as the basis for the godlike status of the classical hero, it also became a distinguishing political-social attribute in the discourses on the ideal ruler. On the other hand, ‘heroic virtue’ was given an extremely precise interpretation in the theological context. In Catholicism from the 17th century onward, heroic virtue achieved an ethical-practical relevance in canonisation procedure. For the step of beatification it became necessary to provide proof of the heroic degree of all the virtues and deeds from the life of the candidate. In delimitation from the classical heroes, the traditional canon of virtues was re‑interpreted in a Christian sense with a particular emphasis on caritas, the love of God and neighbour, in order to demonstrate the ethical superiority of Catholic saints. Forced concepts of sainthood in the post-Tridentine era, such as mystic martyrdom of love or martyrdom attained in charitable service to one’s neighbour,1Gimaret, Antoinette: Extraordinaire et ordinaire des Croix. Les représentations du corps souffrant 1580–1650. Paris 2011: Champion, 563; Fuerth, Maria: Caritas und Humanitas. Zur Form und Wandlung des christlichen Liebesgedankens. Stuttgart 1933: Fr. Frommanns, 124 ff. illustrate the specifically Catholic interpretation of the theological term.

2. The adoption of the Aristotelian term in Christian virtue theory

Aristotle’s brief exposition on heroic virtue at the beginning of his seventh book of Nicomachean Ethics is not given any outstanding importance within his work, but it became the starting point of the term’s complex reception history. Referring to Priam’s praise of Hector, Aristotle took the concept of the ⟶classical hero as his premise: heroic virtue, which only a small number of men had, was a superhuman and divine quality that brought the hero closer to the gods and distanced him from the opposite – beastly crudeness. The heroes attained such an excess of virtue by their own power, for this divine potential was inherent within them like a birthright and elevated them above other men in the sense of an ‘ethical deification’.2Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics 7.1; Homer: Iliad 24.258-259. Cf. Hofmann, Rudolf: Die heroische Tugend. Geschichte und Inhalt eines theologischen Begriffes. Munich 1933: Kösel & Pustet, 3-5, 14; Saarinen, Risto: “Virtus heroica. ‘Held’ und ‘Genie’ als Begriffe des christlichen Aristotelismus”. In: Archiv für Begriffsgeschichte 96.33 (1990), 96-114, 96; Saarinen, Risto: “Die heroische Tugend als Grundlage der individualistischen Ethik im 14. Jahrhundert”. In: Aertsen, Jan A. / Speer, Andreas (Eds.): Individuum und Individualität im Mittelalter. Berlin 1996: de Gruyter, 450-463, 450; Schalhorn, Andreas: Historienmalerei und Heiligsprechung. Pierre Subleyras (1699–1749) und das Bild für den Papst im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert. Munich 2000: scaneg, 43; Disselkamp, Martin: Barockheroismus: Konzeptionen “politischer” Größe in Literatur und Traktatistik des 17. Jahrhunderts. Tübingen 2002: Niemeyer, 34-36; Costa, Iacopo: “Heroic virtue in the commentary tradition on the Nicomachean Ethics in the second half of the thirteenth century”. In: Bejczy, István P. (Ed.): Virtue Ethics in the Middle Ages. Commentaries on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, 1200–1500. Leiden 2008: Brill, 153-172, 155; Fogelberg Rota, Stefano / Hellerstedt, Andreas (Eds.): Shaping Heroic Virtue. Studies in the art and politics of supereminence in Europe and Scandinavia. Leiden 2015: Brill, 1-2. In his work Politics, Aristotle examined the political-social meaning of that pretension, which bestowed on the heroes the status of gods among humans and elevated them above the common norms and laws.3Aristotle: Politics 3.13. Cf. Tjällén, Biörn: “Aristotle’s Heroic Virtue and Medieval Theories of Monarchy”. In: Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt (Eds.): Shaping Heroic Virtue, 2015, 56-58; Saarinen, Risto: Luther and the Gift. Tübingen 2017: Mohr Siebeck, 148-151.

Through more profound explanations, which were later adopted in mediaeval Latin commentaries, the Greek commentaries on Nicomachean Ethics gave the Aristotelian concept even more importance. Precisely because this category of virtue stood apart from the common theory of virtue relevant to humans, its description drew increased attention. As an anonymous commentary written in Greek likely before the mid-13th century explained, the attribute of heroism is interpreted as a superhuman amount of virtue and as a supernatural and admirable quality that primarily higher beings such as the demigods had. Individuals who had heroic virtue must have been in particular union with the gods. Above all other humans, they would be saints in light of their ethical qualities.4Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 30-32; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 451. This culmination of the religious dimension of the heroic in the Greek commentary created the basis for the subsequent Christian interpretation of the Aristotelian term.

The Latin term virtus heroica was introduced in the first Greek-Latin translation of Nicomachean Ethics by Robert Grosseteste (ca. 1175–1253) and was already in common use starting in the early 14th century in Latin commentaries on Nicomachean Ethics and in commentaries on the Sentences (sententiae). Together with the contemporaneously debated question of the distinction between the mercies (dona Spiritus Sancti) and the virtutes, the Christian reception of the classical virtue theory of Aristotle and Plato and of the Plotinian-Macrobian concept of the virtutes purgati animi, which, as a level of virtue in the proximity to God, were associated especially with heroic virtue, offered premises for the Scholastics’ discussion of the Aristotelian term. Beginning in the second half of the 13th century, Aristotle’s concept was gradually incorporated into Christian theology.5Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 32-34, 50, 88-89; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 450. On the Neoplatonic tiers of virtue and their Christian reception, see Kaup, Susanne: De beatitudinibus. Gerhard von Sterngassen OP und sein Beitrag zur spätmittelalterlichen Spiritualitätsgeschichte. Berlin 2012: Akademie, 184. From the Neoplatonic perspective, the cultivation of the virtues resulted in the similarisation with God through the process of a perpetual cleansing of the soul from affective and carnal impulses (virtutes purgati animi). Following Plotinus’s virtue theory, Albertus Magnus was the first one who interpreted heroic virtue in his commentary on Nicomachean Ethics as perfect composure or freedom from the passions. In that godlike state, the actions of the ⟶hero – Albertus refers here to the model of the ideal ruler – remain uninfluenced by lesser motivations, and he follows solely the highest ethical standards of his intellect.6Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 35-43; Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 97; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 452-454; Costa: “Heroic virtue”, 2008, 156 ff.; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 3. By contrast, Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologiae classed the virtus heroica among the gifts of the Holy Spirit: according to Aquinas, the exceptional degree of heroic virtue was not attained through actively ‘rehearsed’ deification, instead presenting it as a mercy, and thus a consequence of divine causation.7Saarinen: “Luther and the Gift”, 2017, 154-157; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 3-4; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 450; Costa: “Heroic virtue”, 2008, 162 ff.; Bonhome, Alfred de: “Héroïcité des vertus”. In: Dictionnaire de spiritualité ascétique et mystique. Vol. VII-1. Paris 1969: Beauchesne, 341.

Even though the mediaeval Scholastics’ examination of the term virtus heroica was inconsistent, shared premises based on Aristotle were apparent: an essential aspect was the distinction between ordinary virtue and heroic or divine virtue. While the former, as virtus moralis, was attainable for all humans who aspired after it, virtus heroica was an exception: it differed from ordinary virtue either through its outstanding qualitative refinement – its utter perfection – or through the supernaturally high quantitative measure of virtue concentrated in an individual. In this latter sense, heroic virtue related to the already well-known canon of virtues. The manifestation of the individual virtues of the canon were potentiated to such a degree that those who had them appeared to be higher beings. Since their heroic actions were extra regulam and guided by divine grace, the Scholastics advised against emulation by those who were only ordinarily virtuous.8Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 9; Saarinen, Risto: “Die heroische Tugend in der protestantischen Ethik. Von Melanchthon zu den Anfängen der finnischen Universität Turku”. In: Rhein, S. (Ed.): Melanchthon und Nordeuropa. Bretten 1995, 132.

Another constant basis of the various discussions of the term by Christian authors was the notion of man as a meta-being between the world of the gods and the animal kingdom. Man’s intermediate position was accentuated in different ways – as sharing in the divine to an extent or as a relation of similarity.9The former was advocated by Thomas – man has “a certain community with the divine beings” – and the latter – the mere similarity with God – by Geraldus Odonis. See Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 455-456; Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 99-100, 112. The pole that formed the strongest antithesis and from which the heroically virtuous, consistent with its nature, distanced itself the most was bestialitas. According to the concept presented by the Scholastic philosopher Jean Buridan (1300–1358), the interplay of a natural tendency towards perfection and the best possible conditioning of moral and intellectual virtues enables an elite to amplify those virtues to a heroic degree. As Albertus Magnus before him, in view of the godlikeness achieved through heroic virtue and the consummately spiritualised form of being that the gods had, Buridan also advocated classifying heroic virtue not just as moral virtue or a regulative of sensual passions, but situating it in the part of the soul imagined to be hierarchically most important: the intellect. Buridan equated wisdom (sapientia), the highest intellectual virtue, with heroic virtue and opened up the possibility not just of seeing it as a moral quality or theological virtue, but also of understanding it to be the highest manifestation of dianoetic virtues (intellectual virtues). While later Catholic authors did not accept Buridan’s extension of heroic virtue, starting in the second half of the 16th century, it was seized on by Protestant ethicists such as Melanchthon (1497–1560). His concept of heroic virtue enabled new substantive links to be made: in later Protestant writings on ethics, heroic virtue was also viewed as an intellectual and artistic virtue (philosophers, musicians, artists) and primarily applied as a political virtue to the notion of absolutist ideal rule (for more detail, cf. ⟶Heroic virtue in Protestantism).10Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 97-98, 101-102; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 456-461; Saarinen: “Luther and the Gift”, 2017, 150-151; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend in der protestantischen Ethik”, 1995, 137-138; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 4, 6-11.

3. Heroic virtue in post-Tridentine canonisation practice

Primary sources from the Middle Ages seldom name specific individuals as exempla of heroic virtue. Nevertheless, there are two noteworthy sources: Thomas Aquinas’s description of Christ’s heroic virtues and Bartholomaeus de Ferraria’s praise of the virtues and life of the not-yet-canonised Catherine of Siena in a sermon in 1411. With the reform of canonisation practice after the Council of Trent (1545–1563), attributing heroic virtue to candidates increased in the causae and in hagiography. This can be explained as compensatory modernisation in view of models of sainthood that were current in the Counter-Reformation: like many late mediaeval candidates before them, most of the post-Tridentine saints could no longer be categorised under the classic ⟶martyr type, but the confessor type. This type, which had been equally recognised since early Christianity, was based on the persecuted Christians who, although they had been able to escape a martyr’s death, professed their Christian faith before their executioners and were adored as saints for their virtuous, ‘angelic’ lifestyle after their release. Their ethical focus was the unconditional preference of divine ends over the concerns of earthly life and could be expressed through a solitary hermit life, ascetic self-restraint, chastity and supernatural occurrences such as miracles. Such a heroic lifestyle was equated to ⟶martyrdom as a moral achievement and could thus compensate the act of self-sacrifice. This type was later expanded quite generally to all saints who did not die a martyr’s death. They were expected to distinguish themselves through charismata bestowed by God and a heroic life of virtue, a model that remains valid through to today.11On the heroic virtues of Christ, see Thomas Aquinas: Summa theologiae III.7.2. Cf. Costa: “Heroic virtue”, 2008, 165; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 5; on the subject in writings by Protestant authors, many of whom also listed Biblical figures among the heroes, see Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 104, 110; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend in der protestantischen Ethik”, 1995, 134-135 and Saarinen: “Luther and the Gift”, 2017, 157. On Catherine of Siena, see “Processus Contestationum super sanctitate et doctrina beatae Catharinae de Senis”. In: Martène, Edmond / Durand, Ursin (Eds.): Veterum scriptorum et Monumentorum historicum, dogmaticorum, moralium, amplissima collectio. Vol. VI. Paris 1729, 1249. Among Catherine’s virtues, primarily her prudentia, temperantia and fortitudo were classified as heroic. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 160; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 44. On the confessor type, see Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 136, 140-145; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 27; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 341-342. In present-day canonisation practice, it suffices to determine the mere authenticity of the martyrdom in a causa martyrum, while it is necessary in a causa confessorum to provide proof of a heroic degree of virtue with a view to the candidate’s entire life.

With the turn of the 17th century, the discourses on the term heroic virtue were revived and carried by the clear interest in an ethical-practical interpretation. Saints of Christian history were cited more and more often as exempla of a heroic degree of virtue, and the term increasingly gained relevance in church law to canonisation procedure. The first causa in which heroic virtue played a role as a criterion of sainthood is the procedure of Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582).12Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 154-155; De Maio, Romeo: “L’ideale eroico nei processi di canonizzazione della Controriforma”. In: Ricerche di Storia Sociale e Religiosa 2 (1972), 139-160, 139; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 337-338. Heroic virtues and heroic deeds are also mentioned with Ignatius of Loyola; see La Canonizzazione dei Santi Ignazio di Loyola Fondatore della Compagnia di Gesù e Francesco Saverio Apostolo dell’ Oriente. Ricordo del terzo centenario. XII marzo MCMXXII. Rome 1922: Grafia, 40, 46. It stands to reason to understand his motto, “Ad maiorem Dei gloriam,” as a heroic direction of will. See Bolland, Johannes / Henschenius, Godefridus / Papebrochius, Daniel (Eds.): Acta Sanctorum: Quotquot toto orbe coluntur, vel à Catholicis Scriptoribus celebrantur. Iulius, Tomus V: Quo dies vicesimus, vicesimus primus, vicesimus secundus, vicesimus tertius & vicesiumus quartus continentur. Antwerpen 1727, 614 (1063): “Tanto denique erga Deum amore flagrabat, ut tota die illum exquireret, & nihil aliud cogitaret, nihil aliud loqueretur, nihil aliud cuperet, quam placere Deo […] Omnes suas cogitationes, verba, opera, in Deum tamquam in finem referebat; ad Deum, ac Dei gloriam, honoremque […].” After her canonisation in 1622, the term heroic virtue appears in the beatification procedures of Cajetan of Thiene (1629) and John of God (1630), finally becoming a customary term in procedure documents and hagiographical texts in the second half of the 17th century after another hiatus in canonisations owing to the papal breve Caelestis Hierusalem cives (1634) of Urban VIII (1623–1644), which was significant to canonisation policy.13Later, heroic virtue regularly appeared in beatification procedures (Francis de Sales, 1661; Rose of Lima, 1668; Pius V, 1672; John of the Cross, 1675; Toribio of Lima, 1679). Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 156; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 338.

Over the course of the 17th century, the term was defined more precisely in a series of theological tracts: like many of the authors who followed him, Francisco Fortunato Scacchi wrote in his work on the veneration of saints (1639) that he saw at the core of all heroicity caritas as the queen of the virtues. Its exceptional manifestation was expressed through a natural congruence of external actions with an internal orientation on the highest transcendent goal (ad finem supernaturalem). Proof of that congruence was, besides the speed and ease (facilè, & promptè) of heroic action (actum virtutis in gradu heroico), the simultaneous expression of charm and delight (suavitas and delectatio).14“Itaque qui elicit actum virtutis in gradu heroico, non solum facilè, & promptè illum eliciet ; verum etiam delectabiliter, & suaviter illum actum producet. Et tanta quidem suavitate, ac delectatione interna fruitur ille, qui heroicum virtutis actum elicit, ut exprimi nequeat: & haec quidem delectatio in actibus virtutum est plena, & perfecta sanctitatis nota.” Scacchi, Francisco Fortunato: De cultu, et veneratione servorum Dei. Liber Primus: De notis, et signis sanctitatis beatificandorum, et canonizandorum. Rome 1639, 151. Of the originally planned eight volumes, only the first was published. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 160-161; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 44; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 338. The later cardinal Lorenzo Brancati de Lauria seizes on the meaning of heroic acts (actiones heroicae), which were the only way to recognise heroic virtue, in his Scotus commentary (1668). As Scacchi argued, heroic action was characterised by speed, ease, delight and an orientation on the highest supernatural goal. And yet the dynamic behind the hero’s actions was not steered by individual achievements of intellect or willpower, but by the influence of the gifts of the Holy Spirit – the hero became a vehicle of divine movement (a Deo motus), which Aquinas attributed to the gifts. Accordingly, Brancati added self-abnegation and utmost self-control to the prerequisites of heroic conduct.15Brancati de Laurea, Lorenzo: Commentaria in III. Librum Sententiarum II. Rome 1668. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 103-112; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 5-6. On the divine movement, see Thomas Aquinas: Summa theologiae I.II.68.1. Cf. Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 103, 112; Costa: “Heroic virtue”, 2008, 163. On heroic virtue as a divine impetus in Protestant ethics, see Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend in der protestantischen Ethik”, 1995, 132. On earlier prototypes, such as the “Afflatus divinus” in Cicero’s writings, see Disselkamp: “Barockheroismus”, 2002, 42-43. In his tract on the moral virtues (De virtutibus moralibus in communi, 1674), the Spanish Jesuit Martin de Esparza Artieda described totalitas (which he also calls puritas) and stabilitas as ⟶heroic qualities. They referred to the complete and unwavering orientation of both will and action on God and arose through an unusually strong intensification of the love of God. An outer sign of heroic virtue was the performed works; the ⟶admiration and adoration of fellow human beings and the occurrence of miracles by which God reveals the saints as such. In his moral-theological work De virtutibus et vitiis disputationes ethicae (1697), the Spanish cardinal José Saenz d’Aguirre also considered these criteria to be decisive, adding to this list following the commandments and abiding by the basic principles of a Christian life. Heroic virtue intensified into the supernatural made the soul immune to influences from outside its transcendent orientation, and Aguirre also named the love of God as its cause.16Esparza Artieda, Martin de: De virtutibus moralibus in communi. Rome 1674, 178-224; Saenz d’Aguirre, José: De virtutibus et vitiis disputationes ethicae. Rome 1697, 465-492. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 99-103.

On the basis of this rich writing tradition, the humanist Pope Benedict XIV (1740–1758, Prospero Lambertini) introduced heroic virtue as a canonistic and legally potent term in his four-volume reform opus De servorum Dei beatificatione et beatorum canonizatione (1734–1738), which still forms a fundamental basis to canonisation procedure today. Drawing mainly upon Brancati and Aguirre, Pope Benedict XIV smoothed out previous heterogeneities in the interpretation of the term and defined clear boundaries between heroic virtue from a Christian understanding and the Neoplatonic virtutes purgati animi. For a beatification procedure to be opened, the heroic degree of virtue (in gradu heroico) now required proof in all known virtues, the cardinal virtues, the Christian virtues, as well as all other subordinate virtues, with the focus resting on the theological virtues and, above all, caritas. Benedict saw another point of emphasis in there being proof of heroic virtue through heroic acts that – as outstanding achievements performed with ease and delight – were to extend into the areas of different virtues.17“[…] adeo non sufficere probationem unius virtutis, sed omnium probationem requiri : non ita quidem, ut Beatificandus, et Canonizandus debuerit in omnibus heroice se exercere, cum sufficiat, sicuti dictum est, ut Heros fuerit in fide, spe, et charitate, et eodem modo Heros fuerit in eis virtutibus moralibus, in quibus juxta statum suum potuit se exercere, cum praeparatione animi ad sic se gerendum in aliis; si occasio oblata fuisset eas exercendi.” Lambertini, Prospero: De servorum Dei beatificatione et Beatorum Canonizatione. Vol. 3. Rome 1840, 221. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 90, 159-167; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 450; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 44-46; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 338-341.

4. Saints as the ‘better heroes’ – the Christian surpassing of the classical hero

In full awareness of the various discourses on heroic virtue, Benedict opens his treatise De servorum Dei by delimiting the apotheosis of the classical ruler and the hero from the tradition of early Christian martyrs and the canonisation of Christian saints.18Lambertini: “De servorum”, 1839, Vol. 1, 1-3. Cf. Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 41. Favouring the latter, his argumentation follows the customary stance of early Christian authors, Augustine in particular. In De civitate Dei, Augustine posited that the classical heroes were surpassed by the Christian saints. He therefore described it as desirable to confer upon the martyrs the honorific of Christian ‘heroes’, provided that any and all pagan connotation could be removed in the process: ‘heros’ originated from ‘Hêrê’, the Greek name of the goddess Juno, who in the skies kept company with the demons and the heroes, the souls of the departed who had been particularly outstanding. As followers of the true religion, the Christian martyrs, however, revealed themselves to be the actual heroes, who through divine virtues were superior to Juno and the traditional heroes along with the demon hordes. The parallelisation and – by demonstrating their superiority – simultaneous delimitation of Christian saints from the classical heroes formed a constant in Christian thinking, with the reference to the superior endowment with virtues in the sense of theological virtues being decisive.19Aurelius Augustinus: De civitate Dei, 10th Book, Ch. 21. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 139; Speyer, Wolfgang: “Heros”. In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum. Vol. XIV. Stuttgart 1988: Hiersemann, 875; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 43; Disselkamp: “Barockheroismus”, 2002, 37-38. On the distinction between heroes and demons, see Plato: Kratylos, 398D. On the superiority of saints over the classical heroes, see Geraldus Odonis: Sententia et expositio cum quaestionibus super libros Ethicorum Aristotelis. Venice 1500, 139; Faber Stapulensis: Commentarii in X libros Ethicorum. Paris 1505, Vol. VII, 1. Cf. Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 100-101. Also Scacchi: “Quae non horrenda quidem monstra cum Hercule, sed quod longe difficilius est Diaboli tentationes, carnis, & mundi irritamenta sordida, fortissime superarunt?” Scacchi: “De cultu”, 1639, 155.

The discourse on the conspicuous relationship between heroes and saints, which had been relevant since late antiquity, was joined in the early modern period by the use of a language informed by classical formulae, that panegyrically endowed the saints with predicates of classical heroism.20Mestwerdt, Paul: Die Anfänge des Erasmus. Humanismus und “Devotio moderna”. Ed. by Hans von Schubert. Leipzig 1917: Haupt, 42-44; Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 159, 163; Loomis, C. Grant: White Magic. Cambridge, Massachusetts 1948: The Medieval Academy of America, 15; Rahner, Hugo: Griechische Mythen in christlicher Deutung. Freiburg im Breisgau 1984: Herder, 25; Speyer: “Heros”, 1988, 870-875; Angenendt, Arnold: Heilige und Reliquien. Die Geschichte ihres Kultes vom frühen Christentum bis zur Gegenwart. 2nd edition. Munich 1997: Beck, 21-23; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 43. The integration of the Aristotelian term of heroic virtue also made clear that there were no longer any reservations on the part of Christians about at least rhetorically linking the heroic with the holy. Benedict’s emphasis of the actiones heroicae appeared to draw directly on the topos of the classic ⟶heroic deed, for like the classical hero, the saints were to distinguish themselves as benefactors, thaumaturges, rescuers, healers or battlefield helpers to the community of faith relevant to them. As explanation for the superiority of the saint over the classical heroes Christian authors listed, on the one hand, their better historical documentation through the diversity of sources and eyewitnesses and, on the other hand, their congruence with the Christian canon of virtues.

4.1. Saints as caregivers and rescuers of the sick

Numerous charitable religious orders newly founded in the 16th century took extraordinary strides to embrace the post-Tridentine emphasis of caritas as the highest Christian virtue, becoming valuable institutions through the establishment of hospitals and the systematic care of the sick, primarily during the plague epidemics. The most important caregiving religious orders that were newly founded starting in the 16th century were recognised by the pope, and their founders, like John of God and Vincent de Paul, were canonised in the 17th and 18th centuries. As the first candidate of his pontificate, Benedict XIV beatified and canonised Camillus de Lellis, the founder of the Order of the Ministers of the Sick (Chierici Regolari Ministri degli Infermi), also known as the Camillians, in the span of only a few years (1742 and 1746). Additionally, at a panegyrical level, he bestowed on him the title of a martyr of love (Charitatis Martyres). The great personal commitment that the Camillian vows demanded urged a ⟶heroization of the saint’s charitable service in the record of his life.

Case study: Camillus de Lellis carrying the sick

A painting by Pierre Subleyras gifted to Benedict for his chambers after the canonisation programmatically reflects the new accentuations of his reform (fig. 1).21Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 17-18, 124. On the painting and the extant initial studies, see the exhibition catalogue: Michel, Olivier / Rosenberg, Pierre (Eds.): Subleyras. 1699–1749 (Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, 20 February – 26 April 1987; Rome, Académie de France, Villa Medici, 18 May – 19 July 1987). Paris 1987: Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 307-313, Nos. 101-104. An episode from Camillus’ life was chosen as the subject of the painting that eyewitnesses had affirmed: his rescue of the infirm from the Roman hospital S. Spirito during the Tiber flood of 1598, which he had foreseen.22Cicatelli, Sanzio: Leben des Kamillus von Lellis. Transl. by Maximilian Fellner and Franz Neidl. Rome 1983 (Viterbo 1615): Generalat der Kamillianer, 178. Camillus is portrayed in the painting carrying patients, a common type of portrayal at the time for depicting charitable ministry to one’s neighbours which could go as far as sacrificing one’s own life.23Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 114-117. Placing one’s own life in the service of the sick was a part of the vows of the Camillian Order. The portrayal type of carrying the infirm was also used with John of God and Aloysius Gonzaga. The account survives of John of God’s rescue of the sick during the 1549 fire at the Royal Hospital of Granada. During the 1590/91 plague epidemic in Rome, Aloysius Gonzaga is to have carried on his back a plague victim to the next hospital and died a short time later himself from a fever. More generally on the central importance of the new charitable orders, see De Maio: “L’ideale eroico”, 1972, 151.

Although Carlo Solfi did speak of Saints Germanus and Martyrius as well-known early Christian paragons of this form of benevolence when recounting the rescue of the sick from S. Spirito in his history of the Camillian Order, Solfi devoted far more attention to his comparison of Camillus with Aeneas, who had carried on his shoulders his decrepit father Anchises out of the burning city of Troy (cf. source 1).24Aeneas’s role as the progenitor of Rome and his flight from Troy establish a typological link between the ancient cities of Troy and Rome and could be interpreted from the Christian perspective as the overcoming of pagan culture. On the Vergil quote “Una salus ambobus erit” as part of the emblem for the prince’s benevolence, see Henkel, Arthur / Schöne, Albrecht (Eds.): Emblemata. Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart 1967/1996: J.B. Metzler, 440.

“Egli medesimo per animare gli altri si diè con alcuni de’ Suoi à portar su’l dorso molti degl’ Infermi; redendo di se stesso verace historia, ciò che di Enea favoleggiò l’Antichità, il quale presosi sù gli omeri, e sottratto il vecchio Padre dall’ incendio d’Ilio, rimase illeso trà le fiamme, riverito come simolacro della Pietà. Nun punto aggravato da quel peso, tutto cuore trà i pericoli di quella inondatione, potea ripetere con quel Troiano Eroe: Nec me labor iste gravabit, Quo res cunque cadent, unum, & commune periclum, Una salus ambobus erit. Così vecchio, & indisposto com’ egli era, ingagliardito da suoi fervori sottrasse dalla sommersione tanti poveri languenti, collocandoli in posto sicuro da tanto pericolo.”

“In order to inspire the others, he began, together with a number of his own, by carrying many of the sick on his back. Single-handedly, he turned into a true story that which antiquity fabulated about Aeneas, an admired symbol of compassion who took his old father on his shoulders so that he could escape the burning of Troy and remain unharmed between the flames. Not encumbered by the weight at all, but utterly encouraged amid the dangers of the flood, he [Camillus, note from the author] was able to say together with that Trojan hero: this labour will be no effort for me. Whatever happens: together, we face the same danger, and the same salvation will also be bestowed upon us. As old and unfit as he was, strengthened by his zeal, he wrested many of the ailing from ruin by bringing them to a place that was safe from all those dangers.”

Source: Solfi, Carlo: Compendio historico della religione de’ chierici regolari ministri degl’ infermi. Mondovì 1689, 70-71 (Transl. by the author).

As an example for the Christian understanding, Solfi’s comparison of Camillus’s superiority as a hero reveals that, while the historian from the Camillian order classes Aeneas among the legendary, he considers Camillus to be verifiable recent past. In the flight from pagan Troy, Aeneas saved his own father out of sympathy, as an expression of his pietas. By contrast, in the Roman hospital Camillus shouldered many of the infirm with whom he was not related as an act of caritas, of unreserved benevolence. Solfi also points out Camillus’s already advanced age and the poor state of his health, alluding to Camillus’s fateful foot wound: because of the repeatedly inflamed wound on his right ankle, he was compelled to put an end to his life as a soldier and decided to join a religious order.25Cicatelli: “Leben des Kamillus”, 1983 (1615), 13-14. An initially unremarkable blister grew ever greater in size “until finally the foot was all around open and gnawed away.” Previously the reason hindering his success in his worldly life, his legs become the symbol of his newly attained strength in his religious life. In Subleyras’ painting, the position of Camillus’s legs greatly contributes to the expression of his power and stability in carrying the infirm. With his habit girded up, his right and actually impaired leg is placed muscularly and healthily on a dry step while the other leg is submerged in the floodwater. Through the position of the legs, the heroic deed – the rescue of the infirm and delivering them into the upper storey – is incisively and visually formulated. The saint’s heroicity is expressed alongside his caritas in the obvious ease and speed with which he, despite a personal handicap, goes on ahead of his fellow friars, all of whom are hesitant, as an exemplum. The columns of the ciborium-covered altar directly behind the group carrying the infirm can be read as a hint to his steadfastness (stabilitas and fortitudo): within the altar is housed a sculpture of Mary holding the Child Jesus, which reflects Camillus’s typological role as Christopher – the bearer of Christ. The appearance of the red cross, the symbol of the Camillian Order, in the upper left corner of the painting signifies the saint’s complete orientation towards the highest goal (fines supernaturalis). Part of the scene’s lighting that directly falls on the apron of the patient-bearer seems to emanate from the cross. The extension of this sight line leads the eye of the beholder to the moral counter-example: a worldly dressed person turned away from the beholder who is evacuating earthly belongings from the site of the catastrophe.26See the thorough analysis of the image in Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 118-126.

4.2. Saints as converted soldiers

A relatively late conversion after an adventurous worldly past, for instance as a soldier in military service against the Turks, represented a biographical model that several canonised founders of religious orders of the 16th century share (e.g. Camillus de Lellis, John of God and Ignatius of Loyola). Like for Camillus, for Ignatius of Loyola, a leg injury that he sustained in the Battle of Pamplona became the reason to devote the rest of his life to following Christ.27Since there were no chivalric romances, his normally preferred reading, where he was convalescing, Ignatius initially read out of boredom hagiographies and Thomas à Kempis’s De imitatione Christi, which led to his conversion. His desire to serve as a knight to a lady and perform great worldly deeds became more and more overshadowed by the joy that he felt in emulating the saints. See Ignatius von Loyola: Bericht des Pilgers. Transl. and commented by Peter Knauer. Würzburg 2015: Echter, 42-47. On Ignatius’s dual role as a secular and religious knight, see Eickmeyer, Jost: “Ignatius, heros contra familiam. Der Gründer der Gesellschaft Jesu als Renaissance-Held im barocken Heroidenbrief des Johannes Vincartius SJ”. In: Aurnhammer, Achim / Pfister, Manfred (Eds.): Heroen und Heroisierungen in der Renaissance. Wiesbaden 2013: Harrassowitz, 115-145. Because his leg healed poorly, a lingering limp resulted and he was denied a further career as a soldier and Spanish nobleman. The weak leg caused him lifelong discomfort, even though he undertook long travels on foot and hid his limp, such that only those who knew of his injury actually noticed it.28Ribadeneyra, Pedro de: Vita del P. Ignatio Loiolae. Venice 1587, 445; Maffei, Giovanni Pietro: De Vita Et Moribus Ignatii Loiolae. Libri 3. Rome 1585, 200. Qualities valued in military contexts, such as discipline and ignoring physical pain, were interpreted at hagiographical level in the sense of Christian notions of sainthood, like corporeal mortification or the topos of saints’ humility, which was ubiquitous in the post-Tridentine period. The description of Ignatius’s heroic virtue in the files on his canonisation procedure link it in particular to his achievements in the struggle against heretics. The notion of sainthood in militant service for the Catholic Church corresponded with its division into the this-worldly chiesa militante and the transcendent chiesa trionfante and the ambitions of Roman universalism. The hagiographical descriptions of the saints’ earlier lives as soldiers thereby served as ⟶prefigurations of their roles within the ‘militia Christi’ that they assumed after their conversion.29On the ‘spiritual militarisation’ of post-Tridentine saints, see De Maio: “L’ideale eroico”, 1972, 149. De Maio notes the relationship between the Ignatian exercises, strictly regulated spiritual practices, and soldierly exercises of discipline. He also delves into the common expression of arma spirituale in the struggle with inner demons.

4.3. Saints as helpers on the battlefield

In view of Old Testament narratives and mediaeval knightly saints, the hagiographical motif of the saint’s appearance or active intervention in historical battles is a phenomenon transcending time that was sweepingly actualised in the second half of the 16th century with the Battle of Lepanto.30Graus, František: “Der Heilige als Schlachtenhelfer – Zur Nationalisierung einer Wundererzählung in der mittelalterlichen Chronistik”. In: Jäschke, Kurt-Ulrich / Wenskus, Reinhard (Eds.): Festschrift für Helmut Beumann zum 65. Geburtstag. Sigmaringen 1977: Thorbecke, 330-348. The various military conflicts with people of different faiths provoked the activation of the notion in retrospectively authored hagiographical texts that military events were influenced by Heaven. For instance, the temporary recapture of Székesfehérvár in 1601 by imperial troops after Turkish occupation was attributed to the Capuchin friar Lawrence of Brindisi, who was present at the battle and responsible for the religious well-being of the soldiers. In contrast to mediaeval battlefield helpers who took part only on the basis of their invocatio from the celestial sphere, Lawrence acted in the thick of the battle as a historical person, which is credited to him in his biography in the sense of the heroic virtue as “celeste efficace virtù”.31Coccallio, Bonaventura da: Ristretto istorico della vita virtu’ e miracoli del B. Lorenzo da Brindisi. Rome 1783, 80. A historical description of the battle can be found in Heile, Gerhard: Der Feldzug gegen die Türken und die Eroberung Stuhlweißenburgs unter dem Erzherzog Matthias von Österreich im Jahre 1601. Rostock 1901.

Case study: Lawrence of Brindisi at the Battle of Székesfehérvár

In the face of the quantitative superiority of the Turks, which had already prompted the leaders of the Christian army to retreat, they were convinced of certain victory over the enemy by a passionate oration from Lawrence, who was renowned throughout the lands for his sermons. To reassure the troops of God’s help, Lawrence went into battle at the head of the army unarmed, holding merely a crucifix in his upraised hand. Astride his horse, he moved with conspicuous speed through the thick of the battle to spur on the troops everywhere and repel the Turks’ flying rifle bullets with the sign of the cross, which either fell to the ground or changed direction and flew back to the enemy artillery. The instinctive movements of his out-of-control horse saved him numerous times from direct Turkish attacks. No rifle bullets could strike him or his horse – one bullet caught in the scant hair of his tonsure, which Lawrence smilingly removed and said: “Ah semplicetta : tu mi volevi offendere!”32Coccallio: “Ristretto istorico”, 1783, 88. The episode of the battle is chronicled in Lib. I, Cap. IX. At the sight of these miracles and the Capuchin friar’s obvious invulnerability, Turks spontaneously converted to Christianity.

To accentuate Lawrence in the thick of the battle, a painting of the event made by Francesco Grandi even before his canonisation uses a pyramidal composition, which is a common technique in ⟶hero portrayals (fig. 2). Nearly in the centre of the scene, he forms the apex of the arranged figures. Raised to the sky, the cross, to which the victory was later attributed, forms the highest point of the figural action radius. Anticipating the imminent victory, Lawrence’s rising movement contrasts with the Turkish horse dramatically falling behind him.33The author is unaware of any art-historical studies on the painting. On the painter Francesco Grandi, see Monte, Michele di: “Grandi, Francesco”. In: Treccani. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 58 (2002). Online at: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-grandi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ (accessed on 20.02.2019).

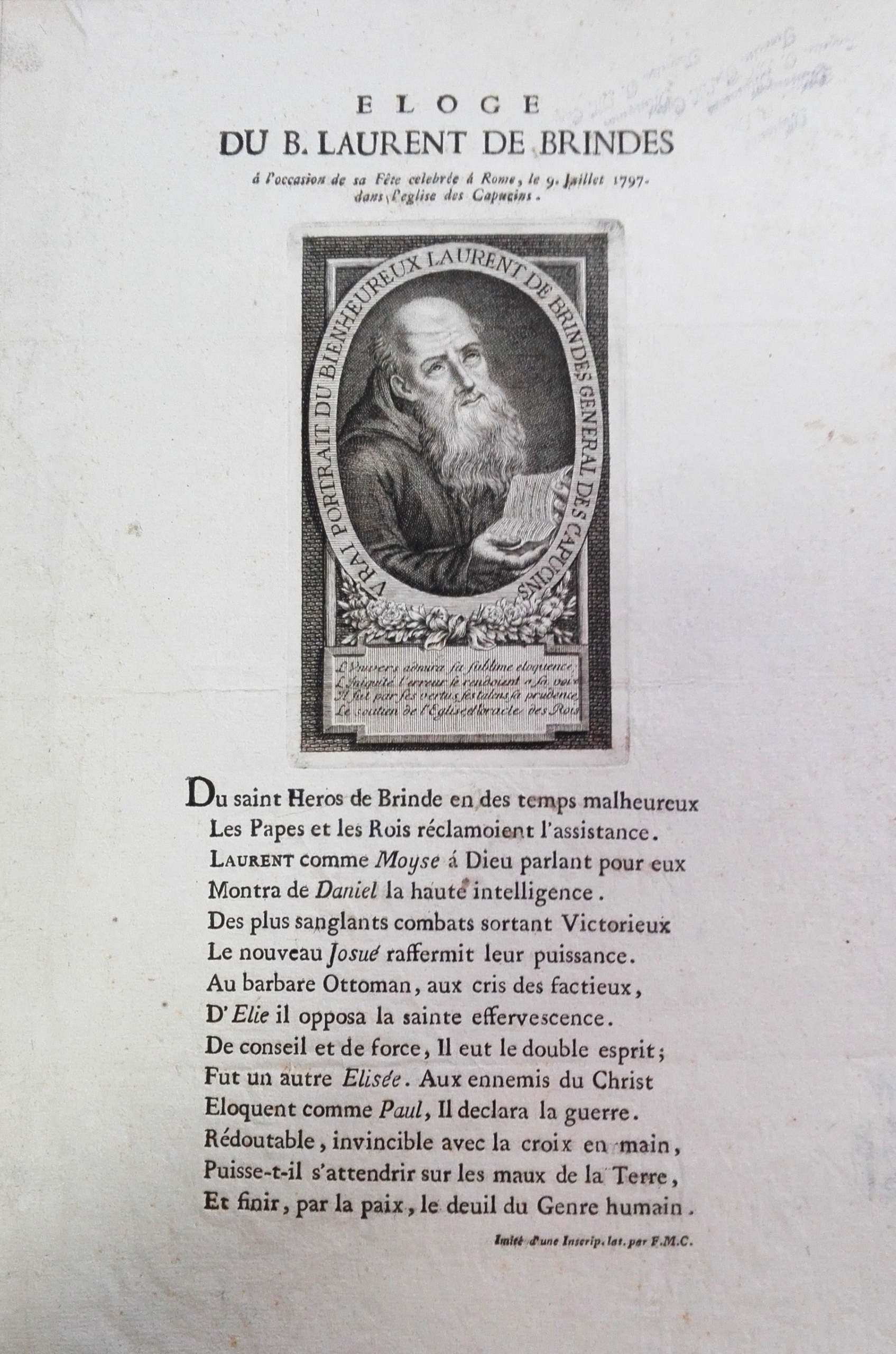

His thaumaturgical works during the battle constitute an important focal point of his characterisation within his Order: a 1797 eulogy praises the beatified Lawrence as the “saint Heros de Brinde”, who, unconquerable through the cross in his hand (invincible avec la croix en main) and eloquent like Paul, declared war against the enemies of Christendom (fig. 3).

5. Heroizations in mysticism: martyrdom of the fire of love

Teresa of Ávila, the founder of the Discalced Carmelite Order, was canonised in 1622 and has been the co-patron saint of Spain alongside Saint James since 1627. She can be considered a precedent of heroic virtue. On 2 February 1602, her supporters at the theological college in Salamanca wrote the petition letter to Pope Clement VIII to open her beatification procedure. The description of Teresa’s virtues refers explicitly to her heroic measure that made her a paragon of the first degree. More than her teachings and writings, the example of heroic virtue that her life was could motivate others to transform how they lived theirs. Like with Catherine of Siena before her, Teresa’s file points out her virtutes purgati animi, the Platonic notion of the cleansing of the soul which Thomas had previously described in connection with heroic virtue. In ascending order, the heroicity of her cardinal virtues and finally of her Christian virtues (faith, hope and love) is described, with her caritas as the ‘mother’ of the love of God and neighbour underscored in particular. With renewed reference to Thomas, Teresa’s receipt of gifts of the Holy Spirit is reasoned directly from her heroic love of God and neighbour (charitatem erga Deum et proximum in heroico gradu). The documents in the file on Teresa’s canonisation procedure emphasise as evidence of her heroic love (signum istius heroici amoris) her numerous ecstasies as well as the strong impetus of her godly love (maximos violentosque impetus amoris Dei), which induced exceptional states of consciousness during which her body even rose into the air. Her famous vision sculpted by Bernini of a seraph piercing her heart with a fiery arrow is mentioned in this context.34On the numerous mentions of Teresa’s heroic degree of virtue, see her canonisation procedure file in Bolland, Johannes / Henschenius, Godefridus / Papebrochius, Daniel (Eds.): Acta Sanctorum: Quotquot toto orbe coluntur, vel à Catholicis Scriptoribus celebrantur. Octobris, Tomus VII: Quo dies decimus quintus et decimus sextus continentur. Brussels 1845, 350 (1061, 1063), 379 (1188), 380 (1194), 381 (1201), 382 (1202), 383 (1208, 1209), 385 (1217), 386 (1220-1226), 398 (1311), 399 (1314), 404 (1336), 410 (1360), 412 (1370), 413 (1371). On the two Thomas references, see “His itaque suppositis, virtutes Beatae Teresiae adeo creverunt ut dictum heroicum gradum attigisse judicaverimus, et quod merito censeri debeant ex illo genere virtutum quas D. Thom. 1. 2, quaest. 61, art. 5, virtutes purgati animi appellat”. Bolland / Henschenius / Papebrochius: “Acta Sanctorum”, Octobris, Tomus VII, 1845, 381 (1201); “[…] et maxime quia charitatem erga Deum et proximum in heroico gradu habuisse ostendimus. Unde sequitur, cum D. Thom. ubi supra, articulo quinto, quod qui habet charitatem, habet omnia dona Spiritus Sancti, quae omnia sibi invicem in charitate connectuntur. Et cum eadem Beata plures actus egregios virtutum et donorum produxerit, qui sunt veri fructus Spiritus Sancti, videtur eisdem fructibus maxime praestitisse.” Bolland / Henschenius / Papebrochius: Acta Sanctorum, Octobris, Tomus VII, 1845, 404 (1336). On Teresa’s ecstasies: “Septimo, praedicta confirmantur ex multiplici fomento quo Christus in ancilla sua flammam vehementer ardentem multo amplius excitavit. Prout quando misit Angelum vultu decorum, qui jaculo ignito illius viscera trajecit et ineffabili amore aestuantia reliquit”. Bolland / Henschenius / Papebrochius: “Acta Sanctorum”, Octobris, Tomus VII, 1845, 386 (1224); “[…] devenit Beata Teresia ad quosdam maximos violentosque impetus amoris Dei, et sic ad frequentes elevationes in ecstasim. Saepissime enim in oratione positam extra se raptam fuisse constat; et quod aliquando adeo vehementibus spiritus elevationibus rapiebatur ut corpus etiam ipsius a terra in altum levaretur”. Bolland / Henschenius / Papebrochius: Acta Sanctorum, Octobris, Tomus VII, 1845, 399 (1314). At the time, levitation was a popular hagiographical motif. What was unique about Teresa’s episodes of levitation was that they took place in public, for instance during mass, particularly communion. See Lavin, Irving: Bernini and the Unity of the Visual Arts. Vol. 1. New York 1980: The Pierpont Morgan Library, 119-120. For a more general perspective of Teresa as a new saint, see Kalina, Pavel: “Mystics and politics: Bernini’s Transverberation of St Teresa and its political meaning.” In: The Sculpture Journal 27.2 (2018), 193-204; Sauerländer, Willibald: Der katholische Rubens. Heilige und Märtyrer. Munich 2011: Beck, 108-117. Having described the vision herself, Teresa related that the vision left her on fire with the love of God – a fellow nun found her afterwards with an enflamed face and had to cut her hair because of the unbearable heat that Teresa felt.35Petersson, Robert T.: The Art of Ecstasy: Teresa, Bernini, and Crashaw. London 1970: Routledge & Paul, 41.

Intense body heat owing to an excess of God’s love was a prevalent phenomenon among post-Tridentine saints that demonstrated the intensity of the mystic experience through actual bodily manifestations: for example, the Jesuit saint and missionary Francis Xavier was known for opening his habit above his breast with a sigh “Satis est, satis est” (“It is enough”). Numerous hagiographical anecdotes likewise recount Saint Philip Neri’s heated states that caused him to fall to the ground, bare his chest and sleep with the window open.36Francis Xavier’s heated states were mentioned in the canonisation bull: “[…] fieretque aliquando talis super eum mentis excessus, ut, oculis in coelum defixis, divina vi a terra elevaretur, vultu adeo inflammatus, ut angelicam prorsus charitatem repraesentaret, nec divini amoris perferre valens incendium, sapius exclamaret: Satis est, Domine, satis est.” “Bulla Canonizationis Beati Francisci Xaverii”. In: Monumenta Xaveriana, ex autographis vel ex antiquioribus exemplis collecta. Vol. II: Scripta varia de Sancto Francisco Xaverio. Madrid 1912: Lopez del Horno, 707. On Philip Neri: “[…] non potendo soffrire sì gran fuoco di amore, di gridare a Dio: non più Signore, non più, e gittandosi in terra, si rivoltava per essa, non avendo più forza per sostenere quell’impeto, che sentiva nel cuore; sicchè non è maraviglia, se essendo così pieno di Dio, sovente dicesse: che ad uno, il quale ama veramente il Signore, non è cosa più grave, nè più molesta quanto la vita, replicando spesso quel detto : i veri servi di Dio hanno la vita in pazienza, e la morte in desiderio.” Bacci, Pietro Giacomo: Vita di S. Filippo Neri Apostolo di Roma e Fondatore della Congregazione dell’Oratorio. Rome 1837, 12. The dictum “Vulneratus charitate sum ego” alludes to Philip’s mystic wound of love, which resulted in the enlargement of his heart and the breaking of two of his ribs. See Bacci: “Vita S. Philippi Nerii”, 1645, 12. The charisma of the gift of tears (dono delle lachrime) constituted an advanced stage of heightened divine love. Those under the influence of that charisma had to fear losing their eyesight. Devotional practices like the contemplative observation of the stars were an expression of the desire to leave behind the earthly world and the corporeal constraints of one’s own body.37Bäumer, Regina / Plattig, Michael (Eds.): Die Gabe der Tränen. Geistliche und psychologische Aspekte des Weinens. Ostfildern 2010: Grünewald; Rieder, Bruno: Contemplatio coeli stellati. Sternenhimmelbetrachtung in der geistlichen Lyrik des 17. Jahrhunderts. Interpretationen zur neulateinischen Jesuitenlyrik, zu Andreas Gryphius und zu Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg. Bern 1991: Lang. Portrayals of levitations and supernatural light phenomena near enraptured saints were highly popular and explain the tendency of the Catholic reform to transfer mystic powers and experiences into the sphere of sensual perception in the sense of the revived motto per visibilia ad invisibilia. The ‘melting’ of the soul and the wounding, purification or baking of the heart in a fiery oven were also metaphorical circumscriptions of transformative processes that regained currency on the basis of mediaeval traditions, such as the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Proceeding from the cultivation of a greatly internalised and intensified mystic practice that involved physical suffering, there was, in view of standardised hagiographical motifs such as the nocturnal fight with demons, the notion of a mystic martyrdom that emphasised the re‑enactment of the Passion by receiving a so-called wound of love, the stigmata or the wounds from the crown of thorns (e.g. Catherine de’ Ricci, Mary Magdalene de’ Pazzi, Veronica Giuliani).38De Maio: “L’ideale eroico”, 1972, 146-148; Lavin: Bernini, 1980, 114, 119. The voluntary sacrifice of one’s life in the form of an ecstatic love-death represents the culmination of this spiritual practice. The canonisation file contains testimony that Teresa died in this manner, leading to her designation as a ‘martyr of the fire of love’ during her liturgical beatification festivities and as a ‘victim of love’ (caritatis victima) later under Urban VIII.39Lavin: Bernini, 1980, 115, 123-124. Bernini incorporated the portrayal of a martyr’s palm into his painting of the Cornaro Chapel.

Mystic literature of the Late Middle Ages, such as that of Denis the Carthusian, laid the groundwork for associating heroic virtue with a maximum of caritas and the highest level of religious life, at which divine grace can be received. Standing in that tradition, Teresa of Ávila defined the highest form of practicing virtue as the actively pursued transmuting union with God.40Teresa de Jesús: Moradas del castillo interior. Ed. by D. Antonio Comas. Barcelona 1969: Bruguera, 7, especially chapter 2, 197-199. The necessity to attain the state of union with God is also central with John of the Cross. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 122. In her autobiography, she speaks of “heroic promises” and the “beginning of contempt for the world, because of a clear perception of the world’s vanity”.41“Such prayer is the source of heroic promises, of resolutions, and of ardent desires; it is the beginning contempt for the world because of a clear perception of the world’s vanity.” Teresa of Ávila: The Autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila. Transl. by Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez, New York 1995: One Spirit, 164 (ch. 19). Her student, the Carmelite John of the Cross whose spiritual poetry stands in the tradition of bridal theology, describes the resolution of the soul to follow its love of God and to transform into the beloved, as a night-time escape of the soul led solely by the light of love: “The soul having to perform so heroic and so rare an act, that being united to the divine Beloved, sallies forth, because the Beloved is to be found only without, in solitude.”42John of the Cross: The Dark Night of the Soul & The Living Flame of Love. Transl. by Edgar Allison Peers. New York 1959: Image Books, 147 (ch. XIV). In Carmelite theology, the heroic degree of virtue corresponds to a wilful union with God and His intellective contemplation through direct vision. Both entail a lasting transmutation of the soul and the receipt of divine graces.43Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 124-129. In his work De gli heroici furori (1585), which was published at the same time as John of the Cross’s “Dark Night of the Soul”, Giordano Bruno uses the Actaeon myth as a metaphor for this process: wilfully seeking union with God, finally experiencing Him and subsequently transforming into what was sought. This is visualised through the hero’s hunt, who deployed his will and his intellect in the form of his bloodhounds and greyhounds to find his prey. Actaeon comes across Diana and, through the direct sight of her divine figure, he is turned into what was once his quarry, a stag, that is killed by the hunting dogs. Bruno’s model of heroic frenzy implies an active subject that wilfully brings about their transformation into the beloved object and submits themselves to the total consummation of their own existence. The orientation of the subject’s will on a divine and partially unattainable object in full awareness of their own mortality heroizes the frenzies described by Bruno. Bruno’s hero “flees the company of the masses, and withdraws himself from common opinions”44Bruno, Giordano: On the Heroic Frenzies. A translation of De gli eroici furori by Ingrid D. Rowland. Text ed. by Eugenio Canone. Toronto/Buffalo/London 2013: University of Toronto Press, 229. and attempts to attain his beloved object through transforming his own nature, i.e. through his fatal self-sacrifice.45Cf. Bruno, Giordano: Von den heroischen Leidenschaften. Transl. and ed. by Christiane Bacmeister. With an introduction by Ferdinand Fellmann. Hamburg 1989: Meiner, 66, 95, 157-159. Cf. Schmidt, Heinz-Ulrich: Zum Problem des Heros bei Giordano Bruno. Bonn 1989: Bouvier, 64-70; Farinelli, Patrizia: Il furioso nel labirinto. Studio su De gli Eroici Furori di Giordano Bruno. Bari 2000: Adriatica Ed., 175-176, 181-184; Klessinger, Hanna: “Heldenhaftes Philosophieren. Giordano Brunos De gli heroici furori”. In: Aurnhammer, Achim / Pfister, Manfred (Eds.): Heroen und Heroisierungen in der Renaissance. Wiesbaden 2013: Harrassowitz, 71-84. Bruno’s model of a spiritual heroism is comparable to Teresa’s in several points: the formation of the heroic subject’s will and his withdrawal in Bruno’s writings correspond with Teresa’s heroic resolutions. With both authors, the unmediated vision or experience, respectively, of the divine leads to the transmutation or injury of the body. The subsequent consumption of the heroic frenzy through the subject’s own powers sent out to the highest object equates to Teresa’s mystic love-death.

Case study: the transverberation of Teresa von Ávila

In addition to being seen as a concrete rendering of her vision, Bernini’s famous portrayal of Teresa’s transverberation in the Cornaro Chapel of the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome is also understood as an allusion to her mystic love-death because of the half-reclined position of her body and her idealised representation. During the experience, Teresa turned into a bride of Christ in supernatural beauty and in ecstasy freely surrendered her soul (fig. 4). Teresa’s idealised facial features and her Manneristically overlong, feeble limbs are enveloped in a voluminous habit, whose vibrating folds leave the body buried within it appearing weightless as if its material substance were dissolving. The placement on a cloud – Teresa’s garment transitions into its structure – and the gesture of the angel drawing Teresa up merely with its fingertips reinforce the impression of complete rapture, just like the massively architectural frame that distances the group from the earthly sphere of the beholder. As Teresa documented regarding her divine experiences, her soul seemed almost to leave her body during the ecstasies46Petersson: The Art of Ecstasy, 1970, 79. On Teresa’s love-death: Lavin: Bernini, 1980, 114. John of the Cross describes the phenomenon in his work The Living Flame of Love. Cf. Johannes vom Kreuz: Die lebendige Flamme. Die Briefe und die kleinen Schriften. Einsiedeln 1964: Johannes, 35-36 (I, 30). – an extreme spiritual and ⟶transgressive experience that Bernini captures through the body’s powerless fall beneath the heavy folds of the habit and the simultaneous upwards movement in following the angel’s hand. The assistance of the angel, who holds in its other hand the arrow, i.e. the implement of the transverberation, makes clear the classification of the heroic love of God as a divine gift of grace in the style of the metaphor prevalent in love poetry of the pierced heart.47Lavin: Bernini, 1980, 109. On the etymological link between the words hero and Eros and the heroes’ existential dependence on the love between gods and men, see Plato: Kratylos 398D. Its equivalent in mysticism was the spiritual wound of love, which was mentioned already by early Christian authorities and embraced in particular in the writings of Teresa’s contemporaries John of the Cross and Francis de Sales.48The mystic wound of love was reserved for a small number of the chosen who were in a state of union with God. John of the Cross describes it as an enticing flame of love that seems to entirely consume souls, but then gives them a new form of being, according to the example of the rebirth of the phoenix. Johannes vom Kreuz: Geistlicher Gesang. Munich 1925: Theatiner, 25 (1, 4); Franz von Sales: Über die Gottesliebe. Zurich et al. 1978: Benziger, 114-115. An important reference is Song of Songs 2:5 “quia vulnerata sum a dilectione”. Cf. Cabassut, A.: “Blessure d’amour”. In: Dictionnaire de spiritualité ascétique et mystique. Vol. I. Paris 1937: Beauchesne, 1724-1729; Crouzel, Henri: “Origines patristiques d’un thème mystique: Le trait et la blessure d’amour chez Origène”. In: Granfield, Patrick / Jungmann, Josef A. (Eds.): Kyriakon. Festschrift Johannes Quasten. Vol. 1. Münster 1970: Aschendorff, 309-335.

6. Literature review and perspectives for future research

While the source material on heroic virtue in political, philosophical and religious writings is extensive, there is a comparably small number of scholarly studies. Delimiting the term in the Catholic-Christian tradition, Rudolf Hofmann has provided what is today the only monograph in an early study based on a broad examination of the sources. He traces in detail the adoption of the Aristotelian term into Scholastic virtue theory and its subsequent instrumentalisation as a criterion of sainthood starting in the 17th century. Bonhome’s exposition on the term in the context of Roman Catholic canonisation decades later was still starkly dependent on Hofmann. De Maio and Suire attempted to integrate Hofmann’s analysis of the different theological lines of discourse into the time-bound contexts in church history. Starting in the 1990s, Saarinen’s publications on heroic virtue in Protestant ethics opened up a theretofore disregarded direction of developing the concept that brought together heroic virtue with the most important context of its historical tradition since the Middle Ages: heroic virtue as ruler virtue. Expanding Hofmann’s exclusively Catholicist perspective, Saarinen introduced distinguishing heroic virtue into moral, religious and intellectual forms. Additional publications such as Disselkamp’s study further pursued expounding on the variety of connections and references that the term’s reception in political theory and intellectual cultural history advanced. To the well-known understanding of heroic virtue offered by Albertus and Thomas, Costa added an interpretation of the term put forth by a group of Parisian ethics commentators that was largely independent of Aristotle and the Christian understanding, whereby he brought attention to the possibility of a non-Aristotelian and non-Christian reception of the term. The edited volume Shaping Heroic Virtue published by Swedish researchers focuses primarily on the political significance of heroic virtue and includes new studies on the influence of classical Roman heroism on early Christian and Neoplatonic notions of holiness in addition to arguing convincingly for expanding the Aristotelian and Neoplatonic source material. Tjällen’s survey of the reception of Aristotle in mediaeval mirrors for princes in particular shows that the significance of heroic virtue as a political virtue played a far more dominant role than previously assumed.49Cf. Saarinen, Risto: Rezension von “Shaping Heroic Virtue: Studies in the Art and Politics of Supereminence in Europe and Scandinavia. Stefano Fogelberg Rota & Andreas Hellerstedt (Ed.)”. In: Scandia 83 (2017), 142-143.

Although the concept of heroic virtue from a theological perspective was developed with precision and in consulting the extensive historical tracts, a more precise study of heroic virtue in canonisation files and hagiographical texts has gone undone. A contextualising examination of the use of the term in mysticism and Christian devotional literature of the 16th century might yield information on the exact context of its increasing relevance starting in ca. 1580 within Christian virtue theory. Except for Schalhorn’s study on the paintings for the pope, there has also been a lack of approaches from visual studies to the question of concrete visualisations of the heroicity of Catholic saints. Furthermore, it also bears examining what new models of Christian heroism and martyrdom developed in view of the specific Christian interpretation of the classic canon of virtues in the post-Tridentine era.

7. References

- 1Gimaret, Antoinette: Extraordinaire et ordinaire des Croix. Les représentations du corps souffrant 1580–1650. Paris 2011: Champion, 563; Fuerth, Maria: Caritas und Humanitas. Zur Form und Wandlung des christlichen Liebesgedankens. Stuttgart 1933: Fr. Frommanns, 124 ff.

- 2Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics 7.1; Homer: Iliad 24.258-259. Cf. Hofmann, Rudolf: Die heroische Tugend. Geschichte und Inhalt eines theologischen Begriffes. Munich 1933: Kösel & Pustet, 3-5, 14; Saarinen, Risto: “Virtus heroica. ‘Held’ und ‘Genie’ als Begriffe des christlichen Aristotelismus”. In: Archiv für Begriffsgeschichte 96.33 (1990), 96-114, 96; Saarinen, Risto: “Die heroische Tugend als Grundlage der individualistischen Ethik im 14. Jahrhundert”. In: Aertsen, Jan A. / Speer, Andreas (Eds.): Individuum und Individualität im Mittelalter. Berlin 1996: de Gruyter, 450-463, 450; Schalhorn, Andreas: Historienmalerei und Heiligsprechung. Pierre Subleyras (1699–1749) und das Bild für den Papst im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert. Munich 2000: scaneg, 43; Disselkamp, Martin: Barockheroismus: Konzeptionen “politischer” Größe in Literatur und Traktatistik des 17. Jahrhunderts. Tübingen 2002: Niemeyer, 34-36; Costa, Iacopo: “Heroic virtue in the commentary tradition on the Nicomachean Ethics in the second half of the thirteenth century”. In: Bejczy, István P. (Ed.): Virtue Ethics in the Middle Ages. Commentaries on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, 1200–1500. Leiden 2008: Brill, 153-172, 155; Fogelberg Rota, Stefano / Hellerstedt, Andreas (Eds.): Shaping Heroic Virtue. Studies in the art and politics of supereminence in Europe and Scandinavia. Leiden 2015: Brill, 1-2.

- 3Aristotle: Politics 3.13. Cf. Tjällén, Biörn: “Aristotle’s Heroic Virtue and Medieval Theories of Monarchy”. In: Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt (Eds.): Shaping Heroic Virtue, 2015, 56-58; Saarinen, Risto: Luther and the Gift. Tübingen 2017: Mohr Siebeck, 148-151.

- 4Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 30-32; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 451.

- 5Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 32-34, 50, 88-89; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 450. On the Neoplatonic tiers of virtue and their Christian reception, see Kaup, Susanne: De beatitudinibus. Gerhard von Sterngassen OP und sein Beitrag zur spätmittelalterlichen Spiritualitätsgeschichte. Berlin 2012: Akademie, 184.

- 6Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 35-43; Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 97; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 452-454; Costa: “Heroic virtue”, 2008, 156 ff.; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 3.

- 7Saarinen: “Luther and the Gift”, 2017, 154-157; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 3-4; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 450; Costa: “Heroic virtue”, 2008, 162 ff.; Bonhome, Alfred de: “Héroïcité des vertus”. In: Dictionnaire de spiritualité ascétique et mystique. Vol. VII-1. Paris 1969: Beauchesne, 341.

- 8Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 9; Saarinen, Risto: “Die heroische Tugend in der protestantischen Ethik. Von Melanchthon zu den Anfängen der finnischen Universität Turku”. In: Rhein, S. (Ed.): Melanchthon und Nordeuropa. Bretten 1995, 132.

- 9The former was advocated by Thomas – man has “a certain community with the divine beings” – and the latter – the mere similarity with God – by Geraldus Odonis. See Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 455-456; Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 99-100, 112.

- 10Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 97-98, 101-102; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 456-461; Saarinen: “Luther and the Gift”, 2017, 150-151; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend in der protestantischen Ethik”, 1995, 137-138; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 4, 6-11.

- 11On the heroic virtues of Christ, see Thomas Aquinas: Summa theologiae III.7.2. Cf. Costa: “Heroic virtue”, 2008, 165; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 5; on the subject in writings by Protestant authors, many of whom also listed Biblical figures among the heroes, see Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 104, 110; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend in der protestantischen Ethik”, 1995, 134-135 and Saarinen: “Luther and the Gift”, 2017, 157. On Catherine of Siena, see “Processus Contestationum super sanctitate et doctrina beatae Catharinae de Senis”. In: Martène, Edmond / Durand, Ursin (Eds.): Veterum scriptorum et Monumentorum historicum, dogmaticorum, moralium, amplissima collectio. Vol. VI. Paris 1729, 1249. Among Catherine’s virtues, primarily her prudentia, temperantia and fortitudo were classified as heroic. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 160; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 44. On the confessor type, see Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 136, 140-145; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 27; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 341-342. In present-day canonisation practice, it suffices to determine the mere authenticity of the martyrdom in a causa martyrum, while it is necessary in a causa confessorum to provide proof of a heroic degree of virtue with a view to the candidate’s entire life.

- 12Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 154-155; De Maio, Romeo: “L’ideale eroico nei processi di canonizzazione della Controriforma”. In: Ricerche di Storia Sociale e Religiosa 2 (1972), 139-160, 139; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 337-338. Heroic virtues and heroic deeds are also mentioned with Ignatius of Loyola; see La Canonizzazione dei Santi Ignazio di Loyola Fondatore della Compagnia di Gesù e Francesco Saverio Apostolo dell’ Oriente. Ricordo del terzo centenario. XII marzo MCMXXII. Rome 1922: Grafia, 40, 46. It stands to reason to understand his motto, “Ad maiorem Dei gloriam,” as a heroic direction of will. See Bolland, Johannes / Henschenius, Godefridus / Papebrochius, Daniel (Eds.): Acta Sanctorum: Quotquot toto orbe coluntur, vel à Catholicis Scriptoribus celebrantur. Iulius, Tomus V: Quo dies vicesimus, vicesimus primus, vicesimus secundus, vicesimus tertius & vicesiumus quartus continentur. Antwerpen 1727, 614 (1063): “Tanto denique erga Deum amore flagrabat, ut tota die illum exquireret, & nihil aliud cogitaret, nihil aliud loqueretur, nihil aliud cuperet, quam placere Deo […] Omnes suas cogitationes, verba, opera, in Deum tamquam in finem referebat; ad Deum, ac Dei gloriam, honoremque […].”

- 13Later, heroic virtue regularly appeared in beatification procedures (Francis de Sales, 1661; Rose of Lima, 1668; Pius V, 1672; John of the Cross, 1675; Toribio of Lima, 1679). Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 156; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 338.

- 14“Itaque qui elicit actum virtutis in gradu heroico, non solum facilè, & promptè illum eliciet ; verum etiam delectabiliter, & suaviter illum actum producet. Et tanta quidem suavitate, ac delectatione interna fruitur ille, qui heroicum virtutis actum elicit, ut exprimi nequeat: & haec quidem delectatio in actibus virtutum est plena, & perfecta sanctitatis nota.” Scacchi, Francisco Fortunato: De cultu, et veneratione servorum Dei. Liber Primus: De notis, et signis sanctitatis beatificandorum, et canonizandorum. Rome 1639, 151. Of the originally planned eight volumes, only the first was published. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 160-161; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 44; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 338.

- 15Brancati de Laurea, Lorenzo: Commentaria in III. Librum Sententiarum II. Rome 1668. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 103-112; Fogelberg Rota / Hellerstedt: “Shaping Heroic Virtue”, 2015, 5-6. On the divine movement, see Thomas Aquinas: Summa theologiae I.II.68.1. Cf. Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 103, 112; Costa: “Heroic virtue”, 2008, 163. On heroic virtue as a divine impetus in Protestant ethics, see Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend in der protestantischen Ethik”, 1995, 132. On earlier prototypes, such as the “Afflatus divinus” in Cicero’s writings, see Disselkamp: “Barockheroismus”, 2002, 42-43.

- 16Esparza Artieda, Martin de: De virtutibus moralibus in communi. Rome 1674, 178-224; Saenz d’Aguirre, José: De virtutibus et vitiis disputationes ethicae. Rome 1697, 465-492. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 99-103.

- 17“[…] adeo non sufficere probationem unius virtutis, sed omnium probationem requiri : non ita quidem, ut Beatificandus, et Canonizandus debuerit in omnibus heroice se exercere, cum sufficiat, sicuti dictum est, ut Heros fuerit in fide, spe, et charitate, et eodem modo Heros fuerit in eis virtutibus moralibus, in quibus juxta statum suum potuit se exercere, cum praeparatione animi ad sic se gerendum in aliis; si occasio oblata fuisset eas exercendi.” Lambertini, Prospero: De servorum Dei beatificatione et Beatorum Canonizatione. Vol. 3. Rome 1840, 221. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 90, 159-167; Saarinen: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1996, 450; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 44-46; Bonhome: “Héroïcité des vertus”, 1969, 338-341.

- 18Lambertini: “De servorum”, 1839, Vol. 1, 1-3. Cf. Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 41.

- 19Aurelius Augustinus: De civitate Dei, 10th Book, Ch. 21. Cf. Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 139; Speyer, Wolfgang: “Heros”. In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum. Vol. XIV. Stuttgart 1988: Hiersemann, 875; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 43; Disselkamp: “Barockheroismus”, 2002, 37-38. On the distinction between heroes and demons, see Plato: Kratylos, 398D. On the superiority of saints over the classical heroes, see Geraldus Odonis: Sententia et expositio cum quaestionibus super libros Ethicorum Aristotelis. Venice 1500, 139; Faber Stapulensis: Commentarii in X libros Ethicorum. Paris 1505, Vol. VII, 1. Cf. Saarinen: “Virtus heroica”, 1990, 100-101. Also Scacchi: “Quae non horrenda quidem monstra cum Hercule, sed quod longe difficilius est Diaboli tentationes, carnis, & mundi irritamenta sordida, fortissime superarunt?” Scacchi: “De cultu”, 1639, 155.

- 20Mestwerdt, Paul: Die Anfänge des Erasmus. Humanismus und “Devotio moderna”. Ed. by Hans von Schubert. Leipzig 1917: Haupt, 42-44; Hofmann: “Die heroische Tugend”, 1933, 159, 163; Loomis, C. Grant: White Magic. Cambridge, Massachusetts 1948: The Medieval Academy of America, 15; Rahner, Hugo: Griechische Mythen in christlicher Deutung. Freiburg im Breisgau 1984: Herder, 25; Speyer: “Heros”, 1988, 870-875; Angenendt, Arnold: Heilige und Reliquien. Die Geschichte ihres Kultes vom frühen Christentum bis zur Gegenwart. 2nd edition. Munich 1997: Beck, 21-23; Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 43.

- 21Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 17-18, 124. On the painting and the extant initial studies, see the exhibition catalogue: Michel, Olivier / Rosenberg, Pierre (Eds.): Subleyras. 1699–1749 (Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, 20 February – 26 April 1987; Rome, Académie de France, Villa Medici, 18 May – 19 July 1987). Paris 1987: Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 307-313, Nos. 101-104.

- 22Cicatelli, Sanzio: Leben des Kamillus von Lellis. Transl. by Maximilian Fellner and Franz Neidl. Rome 1983 (Viterbo 1615): Generalat der Kamillianer, 178.

- 23Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 114-117. Placing one’s own life in the service of the sick was a part of the vows of the Camillian Order. The portrayal type of carrying the infirm was also used with John of God and Aloysius Gonzaga. The account survives of John of God’s rescue of the sick during the 1549 fire at the Royal Hospital of Granada. During the 1590/91 plague epidemic in Rome, Aloysius Gonzaga is to have carried on his back a plague victim to the next hospital and died a short time later himself from a fever. More generally on the central importance of the new charitable orders, see De Maio: “L’ideale eroico”, 1972, 151.

- 24Aeneas’s role as the progenitor of Rome and his flight from Troy establish a typological link between the ancient cities of Troy and Rome and could be interpreted from the Christian perspective as the overcoming of pagan culture. On the Vergil quote “Una salus ambobus erit” as part of the emblem for the prince’s benevolence, see Henkel, Arthur / Schöne, Albrecht (Eds.): Emblemata. Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart 1967/1996: J.B. Metzler, 440.

- 25Cicatelli: “Leben des Kamillus”, 1983 (1615), 13-14. An initially unremarkable blister grew ever greater in size “until finally the foot was all around open and gnawed away.”

- 26See the thorough analysis of the image in Schalhorn: “Historienmalerei”, 2000, 118-126.

- 27Since there were no chivalric romances, his normally preferred reading, where he was convalescing, Ignatius initially read out of boredom hagiographies and Thomas à Kempis’s De imitatione Christi, which led to his conversion. His desire to serve as a knight to a lady and perform great worldly deeds became more and more overshadowed by the joy that he felt in emulating the saints. See Ignatius von Loyola: Bericht des Pilgers. Transl. and commented by Peter Knauer. Würzburg 2015: Echter, 42-47. On Ignatius’s dual role as a secular and religious knight, see Eickmeyer, Jost: “Ignatius, heros contra familiam. Der Gründer der Gesellschaft Jesu als Renaissance-Held im barocken Heroidenbrief des Johannes Vincartius SJ”. In: Aurnhammer, Achim / Pfister, Manfred (Eds.): Heroen und Heroisierungen in der Renaissance. Wiesbaden 2013: Harrassowitz, 115-145.

- 28Ribadeneyra, Pedro de: Vita del P. Ignatio Loiolae. Venice 1587, 445; Maffei, Giovanni Pietro: De Vita Et Moribus Ignatii Loiolae. Libri 3. Rome 1585, 200.

- 29On the ‘spiritual militarisation’ of post-Tridentine saints, see De Maio: “L’ideale eroico”, 1972, 149. De Maio notes the relationship between the Ignatian exercises, strictly regulated spiritual practices, and soldierly exercises of discipline. He also delves into the common expression of arma spirituale in the struggle with inner demons.

- 30Graus, František: “Der Heilige als Schlachtenhelfer – Zur Nationalisierung einer Wundererzählung in der mittelalterlichen Chronistik”. In: Jäschke, Kurt-Ulrich / Wenskus, Reinhard (Eds.): Festschrift für Helmut Beumann zum 65. Geburtstag. Sigmaringen 1977: Thorbecke, 330-348.

- 31Coccallio, Bonaventura da: Ristretto istorico della vita virtu’ e miracoli del B. Lorenzo da Brindisi. Rome 1783, 80. A historical description of the battle can be found in Heile, Gerhard: Der Feldzug gegen die Türken und die Eroberung Stuhlweißenburgs unter dem Erzherzog Matthias von Österreich im Jahre 1601. Rostock 1901.

- 32Coccallio: “Ristretto istorico”, 1783, 88. The episode of the battle is chronicled in Lib. I, Cap. IX.