- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 28. Juni 2024

Inhalt

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Origins of the heroization of labour

- 3. The system of heroizing labour in the Soviet Union

- 4. Transforming concepts

- 5. Heroization of labour in other socialist countries

- 6. Heroization of labour in non-socialist contexts

- 7. Literature review

- 8. Einzelnachweise

- 9. Selected literature

- 10. List of images

- Citation

1. Introduction

Labour heroism is an umbrella term for phenomena of the ⟶heroization of labour, which, originating from the early Soviet Union, are found primarily in communist contexts in numerous variations. Yet, the heroization of labour is not necessarily bound to the communist ideology. It also existed in other political systems and was revived after the fall of the Soviet Union in a number of its successor states in non-communist contexts. At certain points, labour heroism intersects with the transnational and -ideological discourse on the “New Man”, with the figure of the everyday hero and with military heroism (see ⟶soldier [modern era]).

Initially, the heroization of labour concentrated on members of the working class, but was soon expanded to other groups of people, including functionaries, engineers, scientists and artists. Such heroizations focused on both individuals and ⟶collectives. The distinction of individuals invariably emphasised their exemplariness and had an appellative character. In principle, being distinguished for labour heroism was to be attainable for all citizens and aimed at encouraging members of all professions to emulate the role models presented.

The heroization of labour encompassed a broad spectrum of different distinctions, honorific titles and social practices. These constituted a system of reward forms that was constantly evolving and undergoing significant transformation. Important elements were the honorary title “Hero of Labour”, created in the Soviet Union in 1927 and upgraded to “Hero of Socialist Labour” in 1938; the “shock work” campaigns; the “socialist competition”; the “Stakhanovite” movement and comparable movements in communist countries, as well as the numerous ⟶orders and decorations that have been instituted since the 1920s, beginning with the “Order of the Red Banner of Labour of the RSFSR” (1920).

2. Origins of the heroization of labour

The fact that heroes of labour were most prevalent in communist countries suggests that the concept of heroizing labour has its roots in communist ideology. The writings of Marx, Engels and Lenin, however, provide little material in this regard. Although Marx viewed labour as something constitutive for humans that distinguished them from animals, he as well as Engels did not view labour as something heroic. For Marx and Engels, the labourer is not a hero, but a victim of the exploitation in the capitalist system of production. Marx does not elevate the labourer because of his work, but, if at all, as a struggling member of the labour movement, such as the Paris Commune of 1871, and as a member of the historically impactful working class that would one day overcome capitalism. The defeat of capitalist exploitation would be followed by a “realm of freedom”, where “labour, which is determined by necessity and mundane considerations” would cease,1Marx, Karl: Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 3. Ed. by Friedrich Engels. Moscow 1974: Progress Publishers, 820 (“Das Reich der Freiheit beginnt in der Tat erst da, wo das Arbeiten, das durch Not und äußere Zweckmäßigkeit bestimmt ist, aufhört”; Marx, Karl / Engels, Friedrich: Werke. Vol. 25. Berlin 1964, 828). and labour would become something creative and free.

Lenin adopted Marx’s view. In referencing him, Lenin wrote of the “heroism” of the Parisian communards and of the heroic working class. However, it is not labour that is heroized here, but the uprising against the oppression and the establishment of a new socialist society following the successful revolution in Russia.

The heroization of the labourer carrying out his work at the workplace first appears in Lenin’s writings in 1919 during the hardship of the civil war and without any reference to Marx or Engels, but certainly with ideological potential: A Great Beginning. Heroism of the Workers in the Rear was the title of a pamphlet by Lenin from June 1919. The background to this article were the so-called “subbotniki”: in response to an appeal by the party, railway workers had performed unpaid overtime on Saturdays (Russian: subbota) in order to put the paralysed transportation sector back into operation. Lenin described the railway workers’ voluntary additional labour as “one of the cells of the new, socialist society, which brings to all the peoples of the earth emancipation from the yoke of capital and from wars”.2Lenin, V. I.: “A Great Beginning. Heroism of the Workers in the Rear. ‘Communist Subbotniks’”. In: Collected Works. Transl. and ed. by George Hanna. Vol. 29. Moscow 1974 [1919]: Progress Publishers, 409-434, 424. He compared the accomplishments of the workers with those of the soldiers of the Red Army at the various fronts of the civil war and demanded that the “heroism of the working people making voluntary sacrifices for the victory of socialism”3Lenin: “A Great Beginning”, 1974 [1919], 411. be appreciated accordingly:

“The unskilled labourers and railway workers of Moscow (of course, we have in mind the majority of them, and not a handful of profiteers, officials and other whiteguards) are working people who are living in desperately hard conditions. They are constantly underfed, and now, before the new harvest is gathered, with the general worsening of the food situation, they are actually starving. And yet these starving workers, surrounded by the malicious counter-revolutionary agitation of the bourgeoisie, the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries, are organising ‘communist subbotniks’, working overtime without any pay, and achieving an enormous increase in the productivity of labour in spite of the fact that they are weary, tormented, and exhausted by malnutrition. Is this not supreme heroism? Is this not the beginning of a change of momentous significance?”4Lenin: “A Great Beginning”, 1974 [1919], 426-427.

This was the first time that labour was explicitly heroized and equated to the struggle of ⟶soldiers. In logical consequence, military categories were projected onto heroic labour: a few weeks later, Lenin was already writing of “labour discipline” and promised “eternal glory” to those who “march in the front ranks of the army of labour”.5Lenin, V. I.: “Labour Discipline”. In: Collected Works. Transl. and ed. by George Hanna. Vol. 30. Moscow 1974 [1920]: Progress Publishers, 437-438, ibid.

Trotsky rendered this equation of struggle and labour into a systematic militarisation of labour. To prevent the collapse of the food supply, he expected from the labourers in the rear the same willingness to make sacrifices and the same valour as from the soldiers of the Red Army at the fronts of the civil war being waged. Labour was declared an obligation, a duty. In 1920, Trotsky spoke bluntly of the necessity to force labourers to fulfil this obligation just like forcing the soldiers to theirs. Anyone who shirked from the mobilisation of the labour army, refused to work or left his workplace was punished as a “deserter”.6Trotsky, Leon: “About the Organisation of Labour. A Report”. In: The Military Writings and Speeches of Leon Trotsky. Vol. 3: The Year 1920. Transl. and ed. by Brian Pearce. London 1981: New Park, 98-123, 120; see also Trotzki, Leo: “Über die gegenwärtigen Aufgaben des wirtschaftlichen Aufbaus. Rede auf dem IX. Kongress der Kommunistischen Partei Russlands (Moskau, April 1920)”. In: Russische Korrespondenz 1 (1920), Heft 10, 11-19; see also Trotsky, Leon: “About the Organisation of Labour. A Report”. In: 98-123, 120.

3. The system of heroizing labour in the Soviet Union

The militarisation of labour led to the idea to reward workers in a non-material way with medals and public accolades according to the example of soldiers, and to thereby motivate them to make self-sacrifices in fulfilment of their labour obligation. Nikolay Gredeskul, a former liberal jurist who joined the Bolsheviks after 1917, posed this argument in 1920 in his brochure “Liberated Labour”:

“And the militarisation of labour also suggests this thought: if a military punishment – possibly execution by firing squad – follows shirking one’s labour obligation or deserting from labour, then a military award, the same ‘Red Star’ medal just with the inscription ‘for labour’, must be conferred for a great deed in the area of labour. Labour is the foundation of the socialist society; it is due the greatest honour; it is due badges of honour.”7Gredeskul, Nikolaj A.: Befreite Arbeit. Zum Problem der Arbeitsdisziplin. Berlin 1920, 24-25 (“Und die Militarisierung der Arbeit legt auch diesen Gedanken nahe: wenn auf Umgehung der Arbeitspflicht, auf Arbeitsfahnenflucht eine militärische Bestrafung – möglicherweise der Tod durch Erschießen – folgt, – so muß für eine große Tat auf dem Arbeitsgebiete eine militärische Belohnung, derselbe Orden des ‚roten Sternes‘, nur mit der Aufschrift ‚für Arbeit‘ verliehen werden. Die Arbeit ist die Grundlage der sozialistischen Gesellschaft, ihr gebührt die größte Ehre, ihr gebühren Ehrenzeichen.”)

Shortly thereafter, a tiered system of heroizing and honouring labour indeed began to be developed. Instituted in December 1920 as the civilian equivalent to the military honour the “Order of the Red Banner”, the “Order of the Red Banner of Labour of the RSFSR” broke first ground. From 1921 to 1933, it was conferred on 43 collectives and 115 individuals. Recipients of the award were to be groups of workers and individuals who showed particular dedication, initiative, industriousness and organisation in solving economic tasks.

From 1928 onward, that medal was gradually replaced by the “Order of the Red Banner of Labour”, which was instituted for the entire Soviet Union for particular achievements in the fields of the economy, science, culture, education, the arts, health, administration and social engagement. Not just individuals, but also businesses, organisations, cities, territories and republics could be awardees. Between 1928 and 1991, the medal was bestowed more than 1.26 million times.

In 1927, the title “Hero of Labour” was created. It and the title “Hero of the Soviet Union”, which was introduced in 1934 and bestowed for exceptional military achievements, were the highest awards of the Soviet Union. The title “Hero of Labour”, which was conferred from 1928 to 1938 to 1,014 persons, could be given to labourers and other wage earners if they had worked at least 35 years and made particular achievements in the fields of production, science or in service to the state.

The award guidelines reveal that the primary intention was not to elevate members of the working class to ⟶heroes, but to reward outstanding accomplishments of many years in different spheres of activity. This was reflected in the award practice: the first “Heroes of Labour” in 1928 were a textile worker with 50 years of service, who had prevented a boiler explosion; a model builder of a carriage repair centre with 40 years of service, who had made numerous rationalisation proposals; and two teachers, one who was decorated for his successes as an educator and the other for his creation of more than 50 textbooks in the Tartarian language.

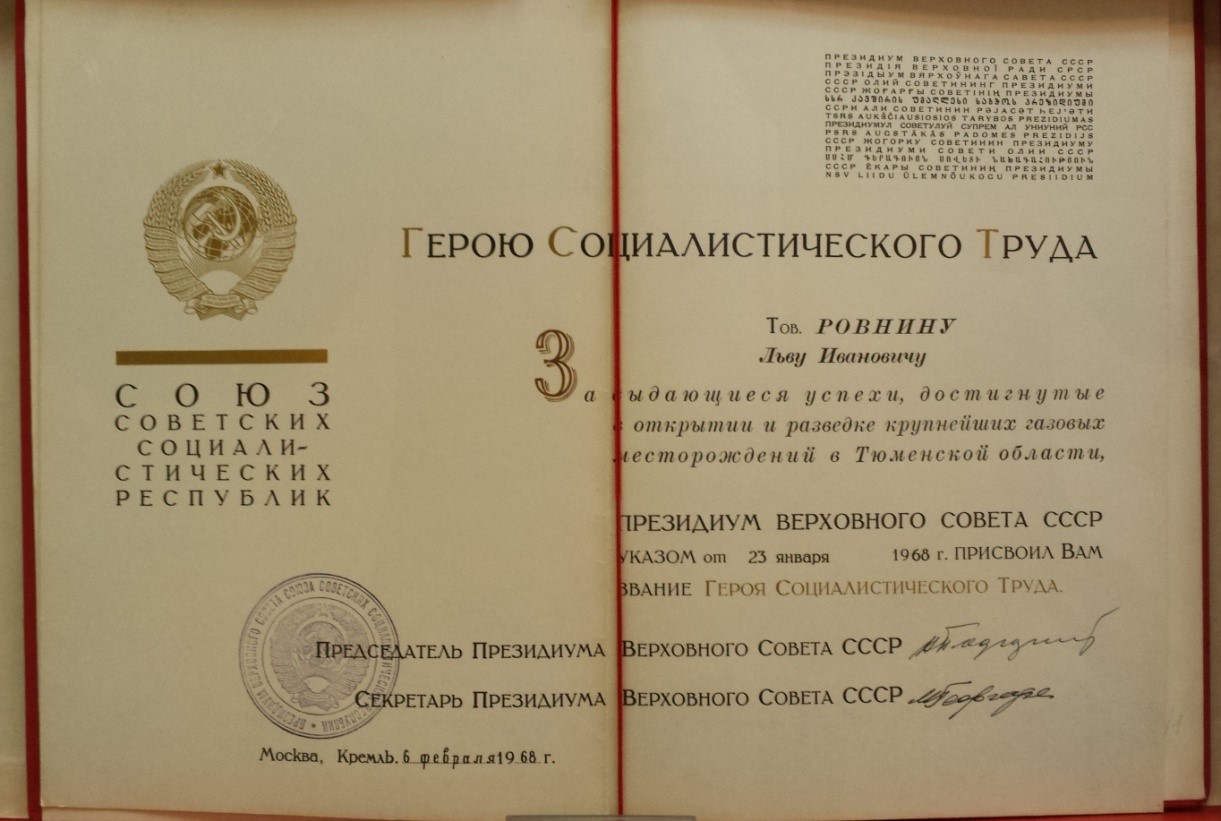

The title “Hero of Labour” was replaced in 1938 by the title “Hero of Socialist Labour”. Ideologically enriched thereby, the title was bestowed on 20,747 persons by the time the Soviet Union ended. With this change, the award-worthy achievements were defined even more broadly and linked more strongly with the economic and power-political interests of the state. The title “Hero of Socialist Labour” could be conferred on persons who had especially distinguished themselves through innovative activities in industry, agriculture, transportation, trade, science and technology. The important factor was that they had contributed to the progress of the national economy, science and culture or that they had promoted the growth of the power and glory of the Soviet Union.

The title was conferred initially as dictated by the primacy of the political and of the wartime economy: the first recipient in 1939 was Stalin personally. During the War, there followed a number of weapons and aeroplane draughtsmen, the people’s commissar for aeronautics, several directors of factories as well as scientists from the arms industry and 127 railway workers, whose services were honoured as an important contribution to the war effort.

Economic and political criteria continued to play a central role after the Second World War as well. In 1947, kolkhozniki were honoured for the very first time. The background was the famine of 1946, which claimed more than one million lives and showed how important it was to resecure the food supply. From 1948 to 1952, roughly 6,000 “Heroes of Socialist Labour” were decorated, the vast majority of whom came from the field of agriculture. In the same period, leading scientists of the Soviet atomic programme were elevated to “Heroes of Socialist Labour”, including the later dissident Andrei Sakharov.

Under Khrushchev, the honouring of agriculture labourers continued, primarily in connection with the Virgin Lands Campaign. An artist was also named a “Hero of Socialist Labour” for the very first time – for his fight against abstract art. At the start of the 1960s, the emphasis shifted to draughtsmen, engineers and others working in the space programme (see ⟶cosmonauts). In the late 1960s and 1970s, writers, actors, composers and musicians were honoured, for example Dmitri Shostakovich and Mikhail Sholokhov. Quantitative high points were the years 1966 and 1971: in 1966, about 3,000 persons were named “Heroes of Socialist Labour”, and in 1971, it was roughly 2,500. In each of those years, a five-year plan ended and the persons were rewarded for particular achievements.

Under Khrushchev and particularly under Brezhnev, the title “Hero of Socialist Labour” turned more and more into a standard bonus for higher functionaries on the occasion of their 60th or 70th birthday. Khrushchev himself received the title three times, Brezhnev once, Andropov and Gorbachev once, Chernenko, who was in office only for one year, three times. Gorbachev finally ended this practice, which had caused the title to be debased among the Soviet people. Instead, he made the popular clown Yuri Nikulin a “Hero of Socialist Labour”.

Apart from being nominally decorated as a “Hero of Labour”, there were even further practices of heroizing labour. The already mentioned “subbotniki” existed until the end of the Soviet Union, just like the practices of engaging in “socialist competition” and elevating innumerable people to “shock workers” and collectives to “shock brigades”. All of these practices served to “mobilise” individuals and collectives to voluntarily perform extra labour.

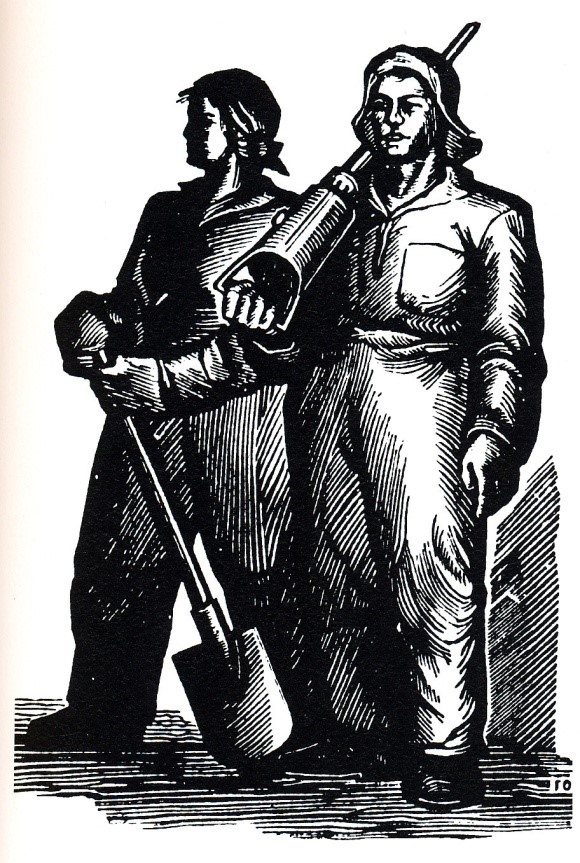

Such practices peaked during the first Five Year Plan starting in 1928, when Stalin gave utmost priority to expediting the industrialisation of the Soviet Union and demanded sacrifice and non-consumption from the populace in order to achieve this aim. “The country must know its heroes” was the title of a two-paged section in the Party newspaper Pravda in which short profiles of labourers appeared daily during the first Five Year Plan. Just as the Stakhanovite movement, these campaigns did in fact also predominantly target labourers, that is, people working manually, and invoked analogies to martial heroism. Cinematic and pictorial (re)presentations displayed muscular ⟶bodies in combative contexts and confident poses. The language was highly militarised. The news on the progress of the industrialisation resembled war reporting. Everywhere fronts were opened, battles waged, charges led and victories had. In the ⟶propaganda of the 1930s, labour turned into the heroic struggle in an imaginary war.

While the reality at construction sites and in factories was far more mundane for most labourers, a solid base of predominantly young activists embraced the ⟶heroism. They acted in the knowledge of being “in active service” and liked to stylise themselves as fighters with the jackhammer at the ready, the tool shouldered like a rifle or the spade at attention. Many young people who had experienced revolution and civil war only as children longed for their own ⟶heroic deeds in order not to take a back seat to the generation of their fathers.

Named after the coal miner Alexei Stakhanov, who in one shift on 31 August 1935 exceeded the extraction norm by 1,457 per cent, the Stakhanovite movement took on a special presence. This – carefully prepared – individual achievement was medially glorified as a heroic deed (see ⟶mediality) and made the starting point of a nationwide campaign that was ostensibly about increasing production, but also about establishing a link between the leader Stalin and a solid base of labourers striving for advancement.

The Stakhanovite campaign was associated with the institution of the “Emblem of Glory” medal in 1935, with which individuals and collectives were awarded for high economic productivity and for particular scientific, cultural or athletic achievements. Renamed the “Medal of Glory” in 1988, this decoration was presented more than one million times by the time the Soviet Union fell. More than two million individuals received the Medal “For Labour Valour”, established in 1938. Another two million were bestowed the Medal “For Distinguished Labour”, also instituted in 1938.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the system of decorating heroes was modified. Those modifications can be classified as being among the efforts of the Brezhnev regime to have as many people as possible partake in state social achievements in order to thereby secure approval. Stalin had demanded sacrifices for building up socialism – Brezhnev announced the era of developed socialism and invested in the welfare state. In 1967, the list of perks for “Heroes of Socialist Labour” was expanded: they permanently received substantial financial benefits and gratuitous special perks. In 1973, the title “Hero of Socialist Labour” received a new statute that raised its visibility: a person was now allowed to be decorated with the title any number of times (the previous maximum was three), and each time the distinguished person additionally received an Order of Lenin.

In 1974, a new award, the “Order of Labour Glory”, was created in reaction to the “Hero of Labour” honorific having waned in prestige because of its inflationary conferment on political jubilarians. As the highest distinction, “Hero of Labour” was attainable only for a relatively small number of people. The “Order of Labour Glory” was aimed at the common ruck of the population. It was awarded in three classes, with the recipient being promoted from one to the next from the third to the first. In lieu of outstanding individual accomplishments, many years of productive labour with one and the same enterprise were rewarded. At first, manual workers from every industry could be decorated. In 1981, the group of possible recipients was expanded to include teachers and educators. The Order’s third class was received by 611,242 persons, the second by 41,218 and the first by 983. Like “Hero of Labour”, the Order entailed financial and social perks.

4. Transforming concepts

The numbers illustrate that the Soviet awards system was aimed primarily at achieving mass appeal. That made highlighting individuals compatible with the ideological primacy of the collective. In principle, everyone had the opportunity to be decorated labour hero, and the awardee served as an example and role model. ⟶Attractive power through ordinariness was a constant feature of labour heroism, which lived on nearness and imitability.

Despite the explicitly established connection to socialism, award practice in the Soviet Union also shows that the norms and values that were conveyed via the heroization of labour were only partially bound to communist ideology. Values such as industriousness, efficiency, dedication, service to the fatherland and loyalty were at least just as important throughout the entire period examined here.

The concepts behind this systematic heroization of labour that aimed to reach broad segments of the population changed over time. Initially, the parallels to the military sphere and the need to motivate workers to render greater service to the development of the economy were very important, but these aspects were accompanied by other notions starting in the 1930s. The heroization of labour became associated with the idea of the New Man: labour heroism was stylised into a method of transforming reactionary individuals into New Socialist Men. A large number of stories of such transformations were popularised through autobiographical texts, novels and films.

The heroization of labouring women also had an emancipatory component by publicising breaks with traditional gender roles. Nevertheless, both in actuality and in medial (re)presentations, masculine and feminine labour heroism proved to have different functions and, particularly in the Soviet case, soon followed gender-specific role models again.

In addition, labour heroism was offered as an avenue of social integration and upward social mobility. In the 1930s, millions of people poured into the cities from forcibly collectivised villages in search of work and lived there in abject conditions at the lower end of the social hierarchy in the enterprises. To these individuals, being named a labour hero meant social advancement and a simultaneous improvement of their living conditions, for the distinction also entailed material perks, such as being allotted housing as well as both monetary and non-monetary awards.

Starting in the 1930s, labour heroism was elevated ideologically to a specific feature of the social order under socialism in order to mark a distinction from the exploitation of workers under capitalism. Economically, labour heroism was purposefully used in order to create incentives in particularly important industries. Politically, it served Stalin particularly during the Stakhanovite campaign as a kind of plebiscite instrument to pressure the leadership of enterprises and to secure the loyalty of a community of followers that had him to thank for their advancement. In the later years of the Soviet Union, the labour hero distinction became more and more an element of a system that purchased the loyalty of functionaries and the population through bonuses and welfare benefits.

5. Heroization of labour in other socialist countries

In the countries in which communist parties took power after the Second World War, practices of heroizing labour were introduced that followed the Soviet example. In particular, the method of spotlighting distinctive role models effectively in media and making them the starting point of mass campaigns based on the example of Alexei Stakhanov found plagiarisers almost everywhere.

For instance, in the Soviet occupied zone of Germany in 1948, miner Adolf Hennecke was selected for accomplishing a record achievement in the style of Stakhanov and was made the object of systematic propaganda. Immediately after his record-breaking shift, a documentary on the “German Stakhanov”, as he soon was called, appeared in the German newsreel Die Deutsche Wochenschau. In the weeks thereafter, he came to fill newspaper headlines. From then on, Hennecke toured the country as a speaker in order to persuade as many people as possible to do the same as him. He found his way into schoolbooks, was (re)presented in numerous images and busts, and treated in novels and narratives. Even after his death in 1975, he functioned as a figure of identification in the German Democratic Republic. It was not until 1973 that he received the title “Hero of Labour”, which the GDR had introduced in 1950 according to the Soviet example.

While Hennecke was on the one hand popular, he and his emulators also met with hostility from many workers, particularly in the earliest period of the campaign, because labour heroism increased the pressure on everyone to perform – a phenomenon that had previously occurred in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. A part of the population responded to the role models by being motivated to work more, or at least acted as if that were so; but some reacted with animosity to the labour heroes because they drove up the quota expectations. It was not an infrequent occurrence for labour heroes to experience ostracisation, resentment and even attacks.

Every socialist country had at least one such preeminent labour hero, and the campaign mechanisms, the forms of medialisation and the people’s reactions were similar everywhere. In Poland, it was Piotr Ożański, a bricklayer, who set sensational records in Nowa Huta in 1950; in Hungary, it was the lathe operator Imre Muszka, who in Stakhanov fashion exceeded his quota by 2,000 per cent in 1949.

The same goes for communist China. In the 1930s, inspired by the Soviet model, the Chinese communists tested out different mobilisation practices as part of production campaigns. From 1943 onwards, those practices became a system that linked the mobilisation of labourers with the notion of the labour hero as well as with a new concept of labour underpinned by Marxist thought and the idea of the “New Man”. Central to Chinese labour heroism was exemplariness, which also found expression in the label “model worker”. In addition to boosting productivity, the primary aim was to explain and publicise new agricultural and industrial technologies, new forms of property and new social relations. Every one of the especially well-known Chinese labour hero(in)es (Wu Manyou, Zhao Zhankui, Li Fenglian, Li Shunda, Geng Changsuo, Wang Guofan, Hao Jianxiu, Zhang Qiuxiang, Chen Yonggui, Wang Jinxi, etc.) stood for such novelty.

6. Heroization of labour in non-socialist contexts

A nuanced study demands asking the question to what extent a heroization of labour or of the worker figure took place or is still taking place in non-socialist contexts. On this subject, literature sometimes references Ernst Jünger’s 1932 book The Worker [Der Arbeiter]. In taking a closer look, however, Jünger’s “worker” turns out to be an idiosyncratic creation that is not to be equated with the common term “worker”, but is to be understood as the antithesis of “citizen” [Bürger]. Jünger’s “worker” is part of a heroic collective supplanting the citizen and creating a novel state through systematic mechanisation and modernisation.

In German National Socialism, the the figure of the worker was heroized. Pictorial and figural (re)presentations of labourers in National Socialism exhibit certain similarities to Soviet labourers, principally as regards their muscular bodies and the parallelisation with fighting soldiers. At the same time, however, important differences are manifest: in Nazi Germany, the elevation and heroization of labour was part of the antisemitic discourse, which contrasted the “creative” German person and the “money-grubbing” Jew. In line with the blood and soil ideology, workers tended to be (re)presented less as industrial labourers and mainly as traditional craftsmen or in agricultural contexts, i.e. as part of a Volksgemeinschaft connected to the land and counterposed to capitalist modernity.

In capitalist contexts, there is no heroization of labour or the worker proper. Although there is a certain connection between the figure of the everyday hero and the labour hero, the former requires an exceptional deed in an exceptional situation, such as rescuing others or preventing a terrible outcome of an occupational accident. While the US Civilian Conservation Corps under President Roosevelt from 1933-1942 cultivated a pronounced masculinity and an appreciation of manual labour through its educational impact on young men, in addition to having a militarising component, it held no explicit heroic potential either of the performed labour or of the men in service.

A number of successor states of the Soviet Union draw upon Soviet heroization practice, although they have otherwise distanced themselves from the Soviet system. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, all of the awards, medals and titles for the heroization of labour were initially abandoned before experiencing a renaissance in some places shortly thereafter:

In Moldova, an “Order of Labour Glory” (“Ordinul Gloria Muncii”) was instituted as early as 1992. To date, it has been awarded to 33 individuals, mainly athletes, scientists, politicians and clerics. In 2000, Transnistria introduced an analogous order, which has been conferred 39 times, primarily to politicians, but also to businessmen, artists, doctors and teachers.

Since 2008, there has been the title “Hero of Labour of Kazakhstan”, awarded for particular achievements in the economic, humanitarian and social spheres and always conferred together with the “Order of the Fatherland”. To date, 27 individuals have been decorated with this title, primarily businessmen. In 2015, Kazakhstan added its own “Order of Labour Glory” to its repertoire of awards, a reiteration of the Soviet order of the same name and also conferred in three classes. Reserved for workers and farmers, this order is associated with the political campaign to “industrialise Kazakhstan anew”.

In 1997, a law was passed in Russia that, in addition to adding new perks, ensured that all “Heroes of Socialist Labour” and the knights of the “Order of Labour Glory” would continue to receive the perks that they had been receiving. In 2013, President Putin also introduced the title of “Hero of Labour of the Russian Federation” in Russia. Putin stated as his reasoning for reviving the title that he wished to reward citizens who rendered outstanding services for their homeland and, at the same time, to establish continuity with earlier generations and eras. In that same breath, he recalled the achievements on the home front during the Second World War. The introduction of the title is therefore one element in the greater context of Putin’s politics of ⟶memory, which aims at drawing upon the greatness and power of the Soviet Union.

The title “Hero of Labour of the Russian Federation” is awarded for “particular services to the state and the people that are associated with the achievement of outstanding outcomes in state, social and economic activities and that are aimed at securing the well-being and prosperity of Russia.” Thirty-two individuals from industry, agriculture, culture, education, sport, medicine and public administration have been decorated thus far, including nine workers, seven managers, three athletes, three artists, three teachers, three functionaries, two professors, one draughtsman and one doctor. Thus, certain priority is given to manual labour and management work in the private sector, but there is also the effort to cover as many different professions as possible and to include both men and women equally.

7. Literature review

While scholars have indeed already discussed the “hero of labour” in individual studies, a systematic exploration of the subject is still lacking. A transnational perspective in particular has thus far been ignored. An initial attempt to bring together individual studies on country-specific manifestations of the “socialist hero” (Satjukow/Gries 2002) has not yet found any continuation. The analytical model provided therein is based on an approach taken from communications theory and describes in ideal-typical terms how heroes are constructed, how they were received among the population and which types of hero were touted in socialist contexts. The edited volume begins with thoughts expressed by Maxim Gorky and Anatoly Lunacharsky in the 1920s on the relationship between the hero and the masses and on the specific characteristics of the “socialist hero”. Gorky’s and Lunacharsky’s thoughts were the subject of an earlier monographic study (Günther 1993) that also establishes links to earlier concepts of heroism, but does not discuss the origins of the labour hero in-depth.

Just recently, a Russian study (Savin 2014) described in detail the shift from civil war heroes to heroes of labour at the end of the 1920s and placed them in the contexts of legitimisation of rulership, social mobility and the restructuring of society through the replacement of traditional hierarchies with new ones. Monographic studies have dealt with individual manifestations of the heroic in the Soviet context, showing how the Stakhanovite movement functioned as a strategy to fortify the rule of Stalinism (Maier 1990), how male and female youths cultivated a heroic habitus within the framework of the Komsomol and carried over conduct and behaviour of the civil war period to compulsory industrialisation and the forced collectivisation of agriculture (Kuhr-Korolev 2005) and, how in doing so, developed the suggestion of an artificial state of war, counterposed their life scripts embodying that “progress” against “reactionary” rural Russia and thereby encouraged the escalation of ⟶violence in times of peace (Neutatz 2001). Militarisation and “bellification” have also been addressed (Isaev 2001, Plaggenborg 1996, Rittersporn 2001), though not yet linked to labour heroism systematically. Overall, research on the labour hero in the Soviet Union has concentrated on the time before the Second World War. Only few attempts have been made for the post-war decades (Yurovsky 2001).

For non-socialist contexts of labour heroism there are a number of profound studies that could serve as points of comparison and starting points for the project, including those on labour service in Nazi Germany and in the US (Patel 2003), on the construction of masculinity in the Civilian Conservation Corps (Stieglitz 1999, Suzik 2005, Martschukat/Stieglitz 2007) on the ideological potential of labour under National Socialism and Italian fascism (Frese 1991, Den Boer/Duchhardt/Kreis 2011, Buggeln/Wildt 2014) and on its aestheticisation (Schirmbeck 1984). Further starting points can also be found in studies on the labour force in the German Kaiserreich (Lüdtke 1993).

8. Einzelnachweise

- 1Marx, Karl: Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 3. Ed. by Friedrich Engels. Moscow 1974: Progress Publishers, 820 (“Das Reich der Freiheit beginnt in der Tat erst da, wo das Arbeiten, das durch Not und äußere Zweckmäßigkeit bestimmt ist, aufhört”; Marx, Karl / Engels, Friedrich: Werke. Vol. 25. Berlin 1964, 828).

- 2Lenin, V. I.: “A Great Beginning. Heroism of the Workers in the Rear. ‘Communist Subbotniks’”. In: Collected Works. Transl. and ed. by George Hanna. Vol. 29. Moscow 1974 [1919]: Progress Publishers, 409-434, 424.

- 3Lenin: “A Great Beginning”, 1974 [1919], 411.

- 4Lenin: “A Great Beginning”, 1974 [1919], 426-427.

- 5Lenin, V. I.: “Labour Discipline”. In: Collected Works. Transl. and ed. by George Hanna. Vol. 30. Moscow 1974 [1920]: Progress Publishers, 437-438, ibid.

- 6Trotsky, Leon: “About the Organisation of Labour. A Report”. In: The Military Writings and Speeches of Leon Trotsky. Vol. 3: The Year 1920. Transl. and ed. by Brian Pearce. London 1981: New Park, 98-123, 120; see also Trotzki, Leo: “Über die gegenwärtigen Aufgaben des wirtschaftlichen Aufbaus. Rede auf dem IX. Kongress der Kommunistischen Partei Russlands (Moskau, April 1920)”. In: Russische Korrespondenz 1 (1920), Heft 10, 11-19; see also Trotsky, Leon: “About the Organisation of Labour. A Report”. In: 98-123, 120.

- 7Gredeskul, Nikolaj A.: Befreite Arbeit. Zum Problem der Arbeitsdisziplin. Berlin 1920, 24-25 (“Und die Militarisierung der Arbeit legt auch diesen Gedanken nahe: wenn auf Umgehung der Arbeitspflicht, auf Arbeitsfahnenflucht eine militärische Bestrafung – möglicherweise der Tod durch Erschießen – folgt, – so muß für eine große Tat auf dem Arbeitsgebiete eine militärische Belohnung, derselbe Orden des ‚roten Sternes‘, nur mit der Aufschrift ‚für Arbeit‘ verliehen werden. Die Arbeit ist die Grundlage der sozialistischen Gesellschaft, ihr gebührt die größte Ehre, ihr gebühren Ehrenzeichen.”)

9. Selected literature

- Buggeln, Marc / Wildt, Michael (Eds.): Arbeit im Nationalsozialismus. Munich 2014: De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

- Chatterjee, Choi: “Soviet Heroines and the Language of Modernity, 1930–39”. In: Ilič, Melanie (Ed.): Women in the Stalin Era. Basingstoke 2001: Palgrave Macmillan, 49-68.

- Farley, James: Model Workers in China, 1949–1965. Constructing a New Citizen. London/New York 2019: Routledge.

- Funari, Rachel / Mees, Bernard: “Socialist Emulation in China. Worker Heroes Yesterday and Today”. In: Labor History 54 (2013), 240-255.

- Günther, Hans: Der sozialistische Übermensch. Maksim Gor’kij und der sowjetische Heldenmythos. Stuttgart/Weimar 1993: Metzler.

- Haynes, John: New Soviet Man. Gender and Masculinity in Stalinist Soviet Cinema. Manchester 2003: Manchester University Press.

- Isaev, Viktor: “Die Militarisierung der Jugend und jugendlicher Radikalismus in Sibirien (1920-Anfang der 1930er Jahre)”. In: Kuhr-Korolev, Corinna / Plaggenborg, Stefan / Wellmann, Monica (Eds.): Sowjetjugend 1917–1941. Generation zwischen Revolution und Resignation, Essen 2001: Klartext, 149-168.

- Jeffreys, Elaine: “Modern China’s Idols: Heroes, Role Models, Stars and Celebrities”. In: PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies 9.1 (2012), 1-32.

- Kuhr-Korolev, Corinna: “Gezähmte Helden”. Die Formierung der Sowjetjugend 1917–1932. Essen 2005: Klartext.

- Maier, Robert: Die Stachanov-Bewegung 1935–1938. Der Stachanovismus als tragendes und verschärfendes Moment der Stalinisierung der sowjetischen Gesellschaft. Stuttgart 1990: Steiner.

- Martschukat, Jürgen / Stieglitz, Olaf: Väter, Soldaten, Liebhaber. Männer und Männlichkeiten in der Geschichte Nordamerikas. Bielefeld 2007: Transcript.

- Neutatz, Dietmar: “Zwischen Enthusiasmus und politischer Kontrolle. Die Arbeiter und das Regime am Beispiel von Metrostroj”". In: Plaggenborg, Stefan (Ed.): Stalinismus. Neue Forschungen und Konzepte, Berlin 1998: Berlin-Verlag, 185-208.

- Neutatz, Dietmar: “‘Schmiede des neuen Menschen’ und Kostprobe des Sozialismus: Utopien des Moskauer Metrobaus”. In: Hardtwig, Wolfgang / Cassier, Philip (Ed.): Utopie und politische Herrschaft in Europa in der Zwischenkriegszeit. München 2003: Oldenbourg, 41-56.

- Neutatz, Dietmar: “Die Suggestion der ‘Front’. Überlegungen zu Wahrnehmungen und Verhaltensweisen im Stalinismus”. In: Studer, Brigitte / Haumann, Heike (Ed.): Stalinistische Subjekte. Individuum und System in der Sowjetunion und der Komintern 1928–1953. Zürich 2006: Chronos, 67-80.

- Patel, Kiran Klaus: “Soldaten der Arbeit”. Arbeitsdienste in Deutschland und den USA 1933-1945. Göttingen 2003: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Rüting, Torsten: Pavlov und der Neue Mensch. Diskurse über die Disziplinierung in Sowjetrussland. Munich 2002: Oldenbourg.

- Sartorti, Rosalinde: “‘Weben ist das Glück fürs ganze Land’. Zur Inszenierung eines Frauenideals”. In: Plaggenborg, Stefan (Ed.): Stalinismus. Berlin 1998: Berlin-Verlag, 267-291.

- Satjukow, Silke / Gries, Rainer (Ed.): Sozialistische Helden. Eine Kulturgeschichte von Propagandafiguren in Osteuropa und der DDR. Berlin 2002: Links.

- Savin, Andrej: “‘Strana dolžna znat‘ svoich geroev’. Sovetskij geroizm kak social’nyj tramplin (1920–1930-e gody)”. In: Vserossijskij ėkonomičeskij žurnal 12 (2014), 159-171.

- Schirmbeck, Peter: Adel der Arbeit. Der Arbeiter in der Kunst der NS-Zeit. Marburg 1984: Jonas.

- Stieglitz, Olaf: 100 Percent American Boys. Disziplinierungskurse und Ideologie im Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933–1942. Stuttgart 1999: Steiner.

- Yu, Miin-ling: “‘Labor Is Glorious”. Model Laborers in the People’s Republic of China”. In: Bernstein, Thomas P. (Ed.): China Learns from the Soviet Union, 1949 – Present. Lanham 2010: Lexington Books, 231-258.

10. List of images

- 1Evgenij Vučetič: Porträt des Helden der sozialistischen Arbeit Nazar-ali Nijazov, 1948, Bronze. Staatliche Tret’jakov-Galerie Moskau.Quelle: Fotografiert von Dietmar Neutatz in einer Ausstellung über den sozialistischen Realismus in der VDNCh, Moskau, März 2016.Lizenz: Zitat nach § 51 UrhG

- 2Linolschnitt eines Arbeiters der Moskauer Metro, Aus der Betriebszeitung „Udarnik Metrostroja“ [Der Stoßarbeiter der Metro], Nr. 197, 24.8.1934, S. 3.Lizenz: Zitat nach § 51 UrhG

- 3Eine Arbeiterin und ein Arbeiter der Moskauer MetroQuelle: Abbildung aus: Rasskazy stroitelej metro [Erzählungen der Erbauer der Metro]. Hg. v. Aleksandr Kosarev. Moskva: Izdatel’stvo „Istorija fabrik i zavodov“ [Verlag „Geschichte der Fabriken und Werke] 1935, S. 224.Lizenz: Zitat nach § 51 UrhG

- 4Aleksandr Dejneka: „Die Stachanovisten“, 1937, Öl auf Leinwand, 121 x200 mm, Staatsgalerie Perm, Russische Föderation.Quelle: Fotografiert von Dietmar Neutatz in einer Ausstellung über den sozialistischen Realismus in der VDNCh, Moskau, März 2016.Lizenz: Zitat nach § 51 UrhG

- 5Urkunde über die Verleihung des Titels „Held der sozialistischen Arbeit“Quelle: Foto von Dietmar Neutatz, 2017.Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

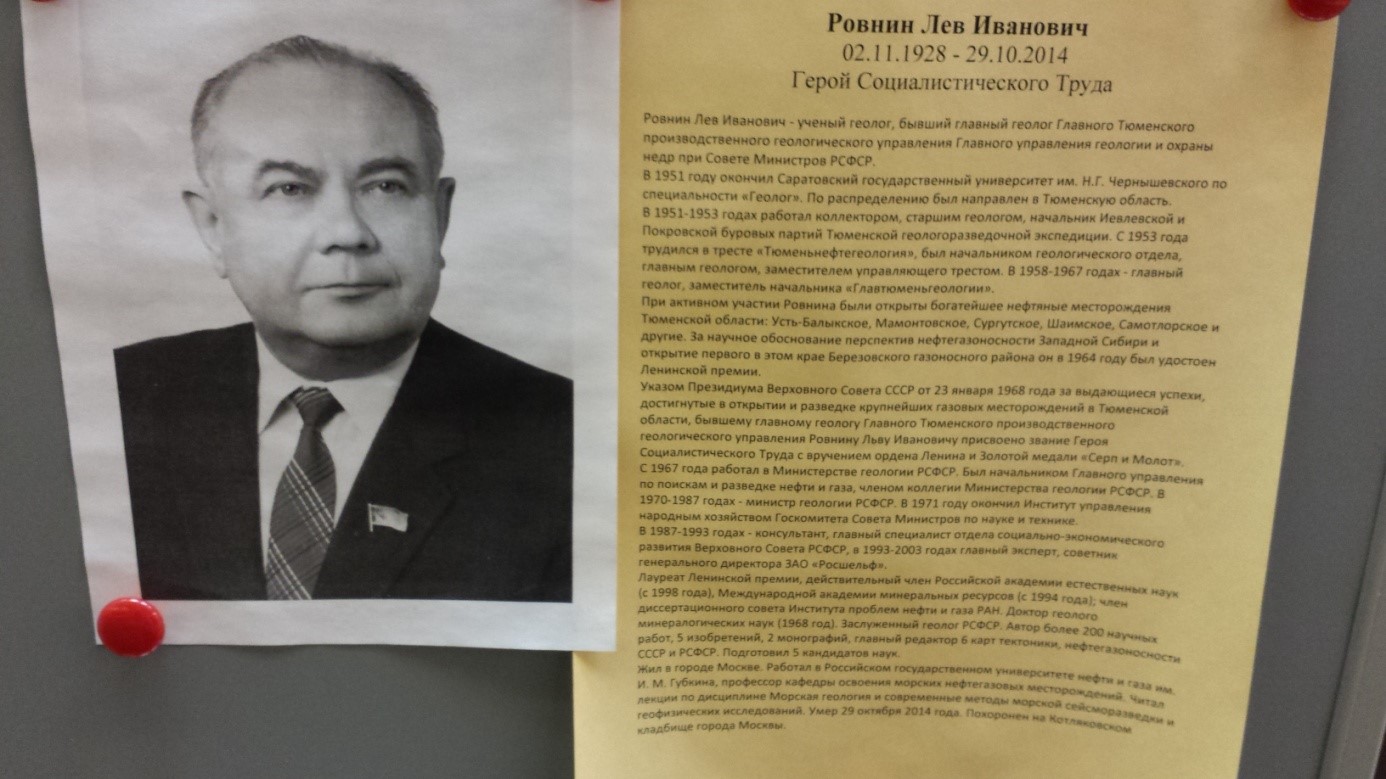

- 6Vitrine mit Erinnerungsstücken, an den Helden der sozialistischen Arbeit Lev Ivanovič Rovnin im Museum der Helden der Sowjetunion und Russlands, Moskau.Quelle: Foto von Dietmar Neutatz, 2017.Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 7Detailaufnahme von Porträt und Kurzlebenslauf, des Helden der sozialistischen Arbeit Lev Ivanovič Rovnin. Museum der Helden der Sowjetunion und Russlands, Moskau.Quelle: Foto von Dietmar Neutatz, 2017.Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

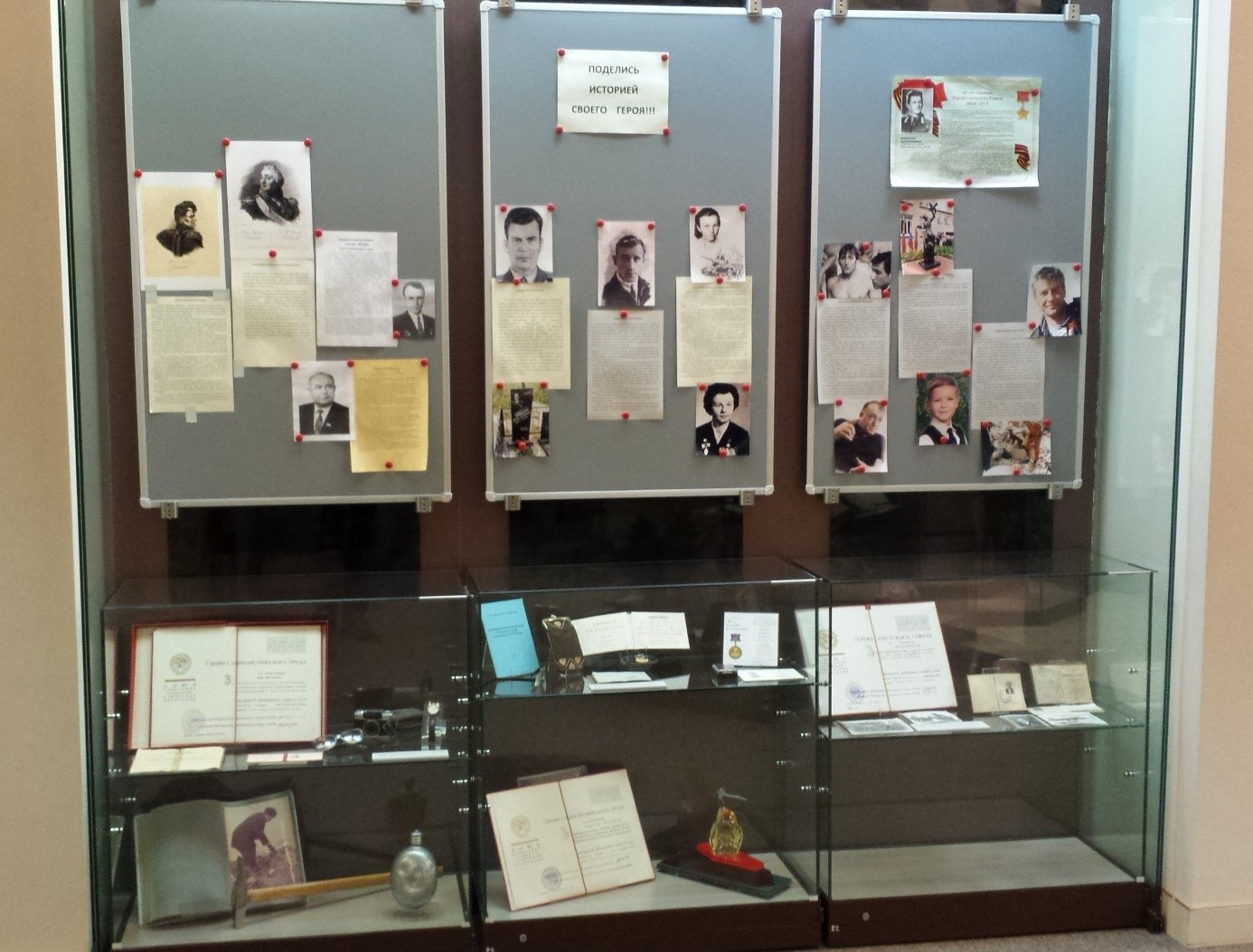

- 8Dreiteilige Pinnwand „Teile die Geschichte deines Helden“, Museum der Helden der Sowjetunion und Russlands, Moskau.Quelle: Foto von Dietmar Neutatz, 2017.Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0