- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 27. Juni 2024

Inhalt

- 1. Definition

- 2. The literary topos

- 2.1. Jacques de Longuyon: Les vœux du paon (1312)

- 2.2. Jan van Boendale’s Leken Spieghel (1325–1333)

- 3. Case study: the Neun Gute Helden in the Hansasaal in Cologne

- 3.1. The Hansasaal

- 3.2. The sculptures of the Neun Gute Helden

- 3.3. The Neun Gute Helden as conveyors of good governance

- 4. Literature review

- 5. Einzelnachweise

- 6. Selected literature

- 7. List of images

- Citation

1. Definition

The ‘Nine Worthies’ (French: neuf preux) are a late mediaeval canon of individual ⟶heroes who were admired for their ⟶virtue and heroism. Initially appearing only as a literary topos, the Nine Worthies eventually also developed into a motif in art history that is found in different media such as painting, fresco, tapestry or sculpture. The selection and ordering of the figures did not follow any set tradition. In the depictions the nine heroes are elevated to ideal representations of knightly bravery whose fame and exemplariness is based on ⟶heroic deeds on the battlefield. The embodiment of knightly role models did not just have purely aesthetic or representative functions, but also pursued appellative and moralising aims.

The Nine Worthies first appeared in literature at the beginning of the 14th century as a list of ideal knights, later giving rise to numerous portrayals in art. This group comprised Hector of Troy, Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar as three heroes of pagan antiquity; Judah Maccabee, King David and the prophet Joshua as the three representatives of the Old Testament; and King Arthur, Charlemagne and Godfrey of Bouillon as three figures representing Christendom. Starting in France the Nine Worthies found visual expression in Germany, Austria, Italy, England and Denmark.1Wyss, Robert: “Die neun Helden. Eine ikonographische Studie”. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 17 (1957), 73-106, 73. The nine heroes were juxtaposed as a counterpart to a group of ⟶nine heroines (French: neuf preuses).

According to Höltgen, “not just the predilection for the numbers game and numerical symbolism, but also the habit of universal chroniclers to divide history in the style of the Bible into several ages of the world” speak to the triadic structure of the group according to the three religions.2Höltgen, Karl Josef: “Die ‘Nine Worthies’”. In: Anglia – Zeitschrift für englische Philologie 77 (1959), 279-309, 280. Translation by Daniel Hefflebower, in the original: “Aus der Gliederung in drei Dreiergruppen gemäß den drei Religionen spricht nicht nur die Vorliebe für Zahlenspiel und -symbolik, sondern auch die alte Gewohnheit der Weltchronisten, die Geschichte in Anlehnung an die Bibel in mehrere Weltzeitalter einzuteilen.” Following the premise of that structure, the nine heroes are particularly incisive persons who represent the entire known world to Europeans at the time. They cover a timespan beginning in pagan antiquity through biblical-Jewish history up to the Christian present, in which the mediaeval knights are situated. The trios hence also correspond to the division of world eras according to Christian salvation history into ante legem (before the law; from Adam until Moses), sub lege (under the law; from Moses until Christ) and sub graita (under grace; since salvation through Christ).3This structuring of history into three periods derives from the epistle of the apostle Paul to the Romans in which he makes that distinction when he writes: “For sin shall not have dominion over you: for ye are not under the law, but under grace.” (Romans 6:14; The King James Bible).

2. The literary topos

2.1. Jacques de Longuyon: Les vœux du paon (1312)

The nine heroes appear as a group for the first time in the poem Les vœux du paon by Jacques de Longuyon, dated to 1312.4Even Johan Huizinga in his 1919 classic of European historiography Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen (English title: The Autumn of the Middle Ages) refers to Jacques de Longuyon’s Les vœux du paon as the first source of the nine heroes topos: “The same inseparability of knightly and Renaissance elements can be found in the cult of the Nine Worthies, ‘les neuf preux’. This group of nine heroes – three pagans, three Jews, three Christians – appears first in chivalric literature: the earliest account is found around 1312 in ‘Vœux du paon’ by Jacques de Longuyon.” Huizinga, Johan: The Autumn of the Middle Ages. Transl. by Rodney J. Payton and Ulrich Mammitzsch. Chicago 1996: The University of Chicago Press, 76. The title of the poem refers to the oaths that were taken by knights at the start of the 14th century. Certain ideals and covenants were invoked in the form of vows that were recited in the name of certain birds: Longuyon’s composition refers to an oath that was made in the name of the peafowl.5Cf. Geis, Walter: “Die Neun Guten Helden, der Kaiser und die Privilegien”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 387-413, 387. The bishop of Liège commissioned Longuyon to write the epic poem, which recounts the deeds of Alexander the Great. Through the title of the work, Longuyon translated the subject into the courtly realm.6Cf. Geis: “Die Neun Guten Helden”, 2000, 387. The fight for the city of Epheson besieged by Clarus, king of India, forms the plot framework of the romance. After the Lady Fesonas had refused him her hand, Alexander rushed to her and selflessly offered his help. Longuyon embeds the stanzas that deal with the nine heroes into the narrative of the decisive battle between the Indian besiegers and Epheson’s defenders. In the poem, Longuyon devotes a distinct verse to each hero, describing their most important heroic deeds.

⟶Hector for instance distinguished himself through his ⟶combative achievements during the Trojan War. He performed the official functions for the city and, according to Longuyon’s version, defeated nineteen kings as well as more than one hundred field commanders and earls. Alexander the Great received his recognition primarily through the account of his victory over Nicolas, the Persian king Darius and his conquest of Babylon. Julius Caesar’s qualities as a field commander and conqueror of England, Alexandria, Africa, Arabia, Syria and Egypt, as well as his victories over Cassivellaunus and Pompey, are praised in the French-language poem. In the group of Old Testament heroes, Judah Maccabee distinguished himself primarily through the killing of Apollonius, Antiochus and Nicanor. Through his pious prayers Joshua parted the waters of the Jordan, making it possible to cross the river. The poet also praises Joshua’s victory over the twelve kings. Longuyon extols David’s successful fight against the giant Goliath as his exemplary deed. Among the Christian heroes, King Arthur stood out as a ruler of Britain through his victory over the giant Ruston, whose cloak was made out of the beards of defeated kings. Charlemagne distinguished himself primarily through his successful battles in France, Spain and the kingdom of Pavia. Longuyon writes that in Jerusalem he reintroduced the institution of baptism and the holy sacraments. The most recent hero from the group, Godfrey of Bouillon, is credited with the victory over Sultan Suleiman as an outstanding deed. As the liberator of the city of Jerusalem, his coronation as king is remembered with due regard in the final verse.

The order and selection of individual heroes that Longuyon made also requires particular attention. For instance, the group can be put into chronological order, beginning from the ancient heroes Hector, Alexander and Caesar, to the Old Testament heroes Joshua, David and Judah Maccabee and through to the Christian heroes Arthur, Charlemagne and Godfrey of Bouillon. Like in a chronicle of world history, outstanding personalities and deeds are recorded for posterity. Accordingly, the nine heroes stand for historical periods that were essentially shaped by their deeds. In this respect, each one of the heroes forms an important caesura in history, stretching from antiquity, beginning with Hector’s fight for Troy, to the contemporary past with Bouillon’s crusade.7In his 1971 exposition on the topos of the English ‘Nine Worthies’ in literature and the fine arts, Horst Schroeder points out the significance of the nine heroes in respect of a summary overview of world history. See Schroeder, Horst: Der Topos der Nine Worthies in Literatur und bildender Kunst. Göttingen 1971: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 49. According to Karl Josef Höltgen (1959), this corresponds “[…] to the personified character of mediaeval historiography to present history not as an objective sequence of events, but as the deeds and fates of outstanding personalities” (Translations by Daniel Hefflebower. In the original: “Die Abfolge der neun Figuren […] bietet eine auf Namen reduzierte Universalgeschichte und entspricht dem personalen Charakter mittelalterlicher Historiographie, Geschichte nicht als objektiven Geschehnisverlauf, sondern als Taten und Schicksale hervorragender Persönlichkeiten darzustellen.”) Höltgen cites as examples “world chronicles and annals that often begin with Adam and mark individual periods of time by one or more names […]” (“Weltchroniken und Annalen, die häufig mit Adam beginnen und einzelne Zeitabschnitte durch einen oder mehrere Namen markieren, zeigen dies Strukturprinzip”). Höltgen: “Die ‘Nine Worthies’”, 1959, 280.

2.2. Jan van Boendale’s Leken Spieghel (1325–1333)

Following Longuyon’s canon of heroes, the Dutch writer Jan van Boendale completed Der Leken Spieghel (Dutch for ‘The Laymen’s Mirror’) between 1325 and 1333. In encyclopaedic form, Boendale compiles the knowledge that was necessary for a moral and exemplary life. In his Volksbuch, the history of the nine heroes is embedded in a narrative beginning with Adam and Eve followed by the history of the Old Covenant and the life of Jesus Christ. After the history of Rome and Christianity, the narrative ends with Christ’s return to Earth and the expectations of the beginning of his thousand-year reign. What follows is a discussion of ethics “in which the poet cautions princes to practice politics that serve the common good; in which parents are encouraged to thoroughly instruct their children, wastrels are called upon to practice moderation and poets are warned to preserve morality.”8Geis: “Die Neun Guten Helden”, 2000, 388. Translation by Daniel Hefflebower, in the original: “Es folgt eine Sittenlehre, in welcher der Dichter die Fürsten zu einer Politik ermahnt, die dem Gemeinwohl dient, in der die Eltern zu gründlicher Unterweisung der Kinder ermuntert, die Prasser zur Mäßigung und die Dichter zur Wahrung der Moral aufgefordert werden.”

For the following examination of the Neun Gute Helden (‘Nine Good Heroes’) in the Hansasaal of Cologne’s Town Hall, Boendale’s work is significant because there are only very few known literary sources of the Nine Worthies topos in Germany.9Cf. Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 79. One of them is a poem written at the end of the 14th century in the Low German dialect. Following the ubi sunt formula, it recounts the story of the ⟶death of each of the nine heroes, pointing to their earthly impermanence. However, the poem does not tell of the heroes’ glory and their brave deeds. The second German text we know of bears the title Von den weltlichen herren (‘Concerning the worldly lords’). It originated circa 1400 and is part of the Kolmarer Liederhandschrift.10Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 79. Therein the poet explores who the most significant profane rulers are, the nine heroes.

Dutch literature on the Nine Worthies is notably more extensive than German literature. Dutch works of poetry found their way to Cologne, where they (unlike the French texts) could easily be understood thanks to the linguistic proximity of Dutch to German. Since the two German textual sources mentioned were not written until around 1400, but the representation of the Neun Gute Helden in Cologne can be dated earlier, it can be assumed that the patrons were aware of foreign-language sources. A commission without knowledge of the literary sources is highly unlikely, for Longuyon defined the classical canon of the Nine Worthies in his Les vœux du paon. Although the author of the Leken Spieghel regrets that Caesar was included in the group of ancient heroes instead of emperor Augustus, he nevertheless does not dare to disregard Longuyon’s established canon and alter the group according to his wishes. This illustrates that Longuyon’s canon of the nine heroes had “already solidified into a literary constant immediately after its publication.”11Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 80.

3. Case study: the Neun Gute Helden in the Hansasaal in Cologne

As a striking example of the reception of the nine heroes in Germany and the adoption of the topos in the fine arts, the portrayal of the Neun Gute Helden in the Hansasaal of the Cologne Town Hall is examined in detail below (fig. 1). The monuments to the heroes were erected there in the 14th century as a group of ideal knightly figures and are considered to be one of the earliest sources of the Nine Worthies in statuary.12Dating the Neun Gute Helden sculptures is a matter of contention in scholarly literature. Bergmann and Lauer date the figures to the time around 1310 due to stylistic parallels to a find of sculpture fragments from the chancel in the Cologne Cathedral. See Bergmann, Ulrike / Lauer, Rolf: “Die Domplastik und die Kölner Skulpturen”. In: Bergmann, Ulrike / Legner, Anton (Eds.): Verschwundenes Inventarium. Der Skulpturenfund im Kölner Domchor: Cologne 1984: Schnütgen-Museum, 40-41. This conjectured period of completion however is likely too early. In his in-depth study, Geis dates the figures to the years between 1320 and 1330 based on convincing arguments. Geis: Die Neun Guten Helden, 2000, 400-401. The reference to Jacques de Longuyon’s Les vœux du paon alone is an argument against the early dating made by Bergmann and Lauer because Longuyon did not write the poem until around 1312. Moreover, the poem was written in French. It was not until Jan van Boendale’s Leken Spieghel that there was a literary example in a language that was also understood by the inhabitants of Cologne. Based on the book’s prevalence, it can be surmised that it was also known to the Cologne public. If these two literary sources are posited as the basis for the group of sculptures, then the date of their completion cannot have been until after 1312 or after the publication of the Leken Spieghel between 1325 and 1333. They offer a model by which to visualise the spread of the topos. Additionally, the array of the group of heroes within the Town Hall structure marks the transition of the subject from the knightly-courtly world to the bourgeois-urban sphere. As exemplars of just governance in a public administration building, they call upon viewers to always advocate for a form of good governance.

3.1. The Hansasaal

At 29 m in length and 7.25 m wide, capped by a 9.70 m high ogival barrel vault ceiling made of wood, the Hansasaal forms the centrepiece of the Town Hall complex.13Cf. Mühlberg, Fried: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte des alten Rathauses zu Köln”. In: Fuchs, Peter (Ed.): Das Rathaus zu Köln. Berichte und Bilder vom Haus der Bürger in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Cologne 1973: Greven, 77-106, 78. Originally called the ‘Langer Saal’ (‘Long Hall’), the room was renamed ‘Hanseatischer Saal’ (‘Hanseatic Hall’) in the 18th century, from which the Saal’s current name ultimately derives. The Hanseatic cities are said to have convened here in 1367 to found the Confederation of Cologne as an alliance in the war against Denmark.14Cf. Mühlberg: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte”, 1973, 78. The Hansasaal’s functions have been manifold: it has served as a place of assembly for the gatherings of various committees and as a courtroom for the council. In addition, the Hall also had a representative function. Primarily the granting of town privileges contributed to the Town Hall becoming one of the most important secular buildings that reflected a growing self-consciousness of the bourgeoisie. Cologne’s Town Hall is the oldest known town hall in Germany.15Cf. Leiverkus, Yvonne: Köln. Bilder einer spätmittelalterlichen Stadt. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2005: Böhlau, 122. Leiverkus points out that Cologne’s Town Hall is mentioned as early as in the first half of the 12th century. The Town Hall stands at a place in the city steeped in history: during Roman rule, the praetorium stood at the same location. Cf. Rauch, Ivo / Täube, Dagmar / Westermann-Angerhausen, Hiltrud (Eds.): Die gute Regierung. Vorbilder der Politik im Mittelalter. Cologne 2001: Schnütgen-Museum, 7. The exact dates of its construction cannot be determined, but the Saal must have been built in the early 14th century and largely been completed by 1341 because it was then declared that the city scribe was to reside “under der burgere huis” (under the citizens’ house).16Cf. Bellot, Christoph: “Zur Geschichte und Baugeschichte des Kölner Rathauses bis ins ausgehende 14. Jahrhundert”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 197-335, 247.

The Saal takes up the entire upper floor of the original Town Hall building; it is located in the second storey of this transverse central piece of mediaeval architecture. Viewed from the west, a good third of it is concealed behind the Renaissancehalle.17Cf. Hagendorf-Nußbaum, Lucia / Nußbaum, Norbert: “Der Hansasaal”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 337-386. On the Saal’s north wall there is a multiform tracery design, now featuring replicas of the eight Rathauspropheten (‚Town Hall prophets‘; fig. 2). The sculptures of the Neun Gute Helden in Gothic pinnacle work are situated on the Hansasaal’s opposing southern wall (fig. 3). Made of stone, the figures stand in a compact row slightly below the southern wall’s horizontal axis on brackets positioned at right angles. Above the pinnacle-crowned baldachins that envelop the individual hero monuments, the substantially smaller sculptures of the emperor and the personifications of the staple right and the fortification right are situated at the tapering end of the lunette.

3.2. The sculptures of the Neun Gute Helden

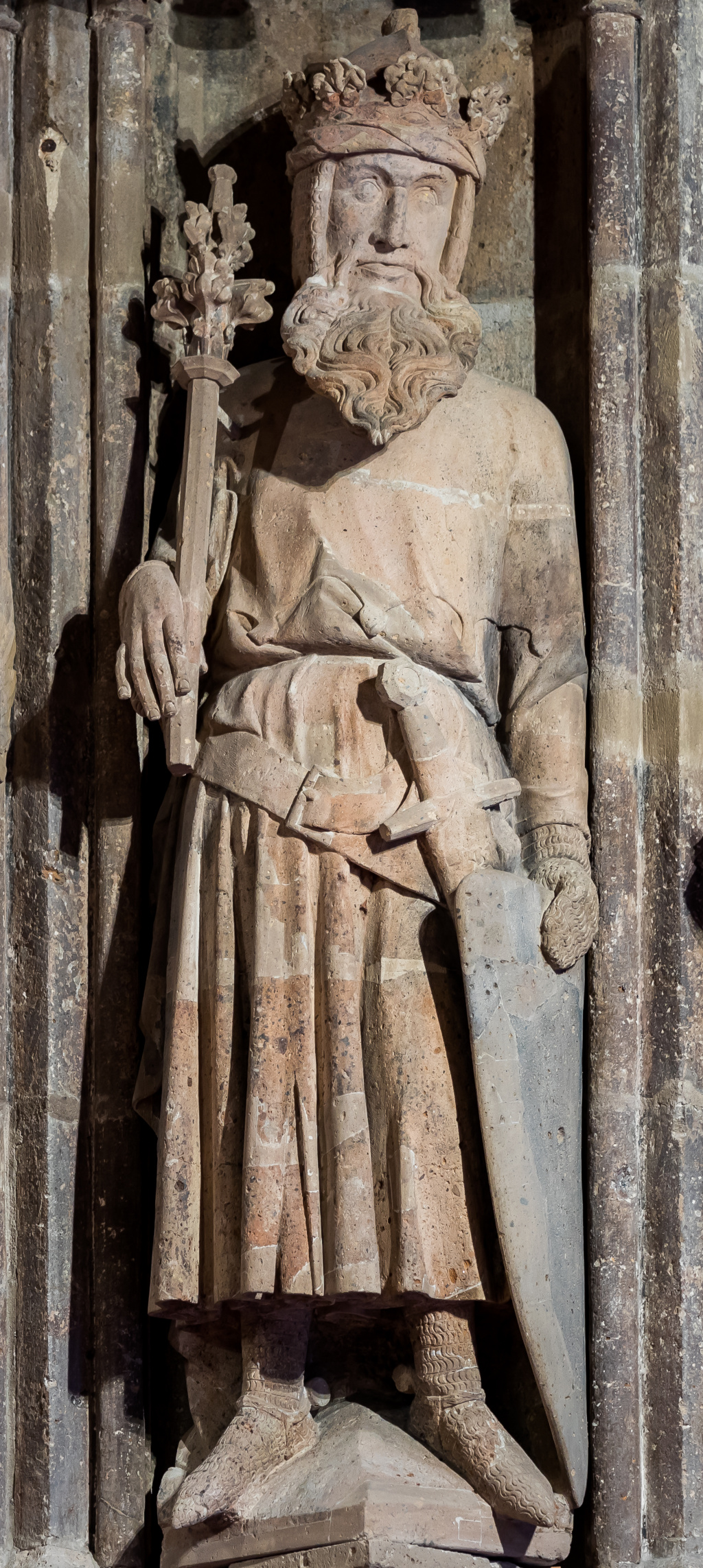

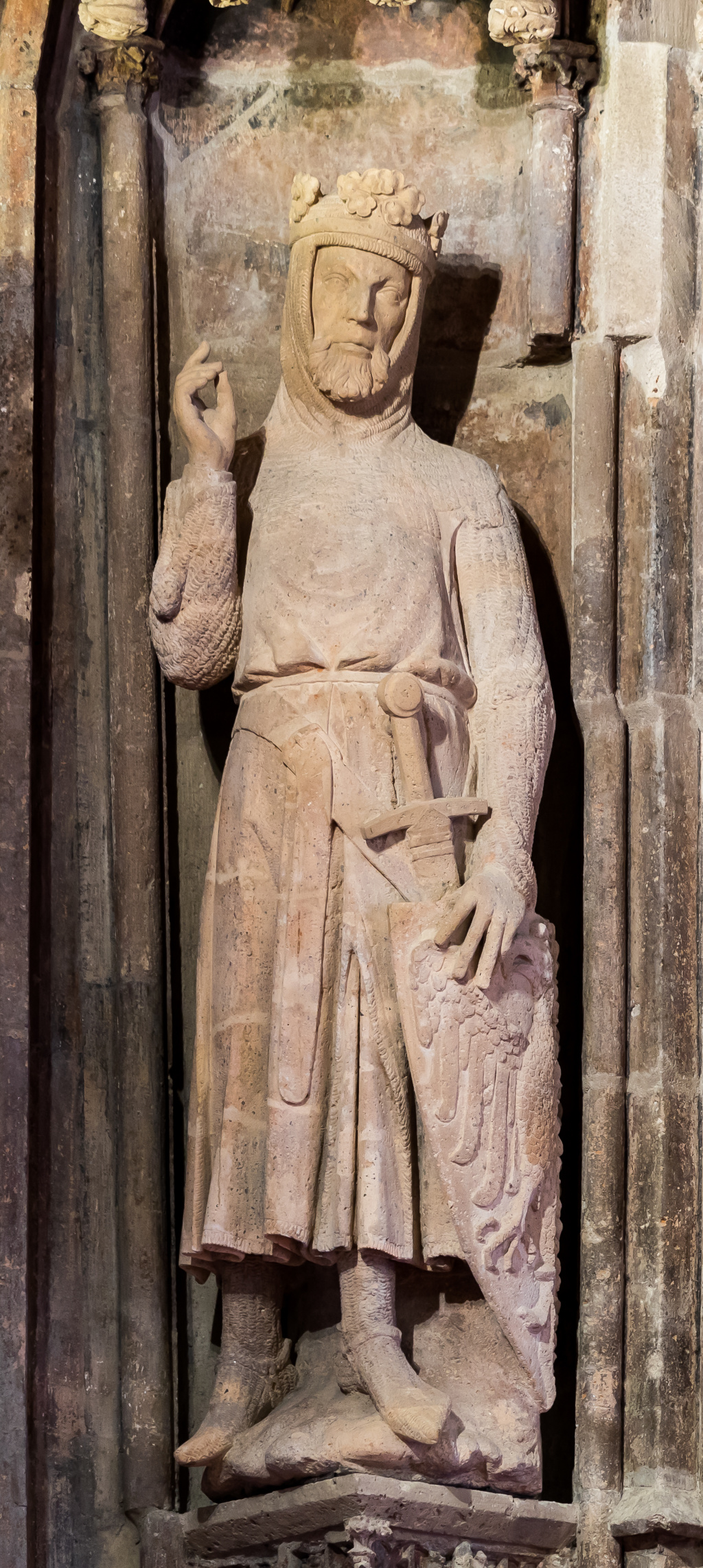

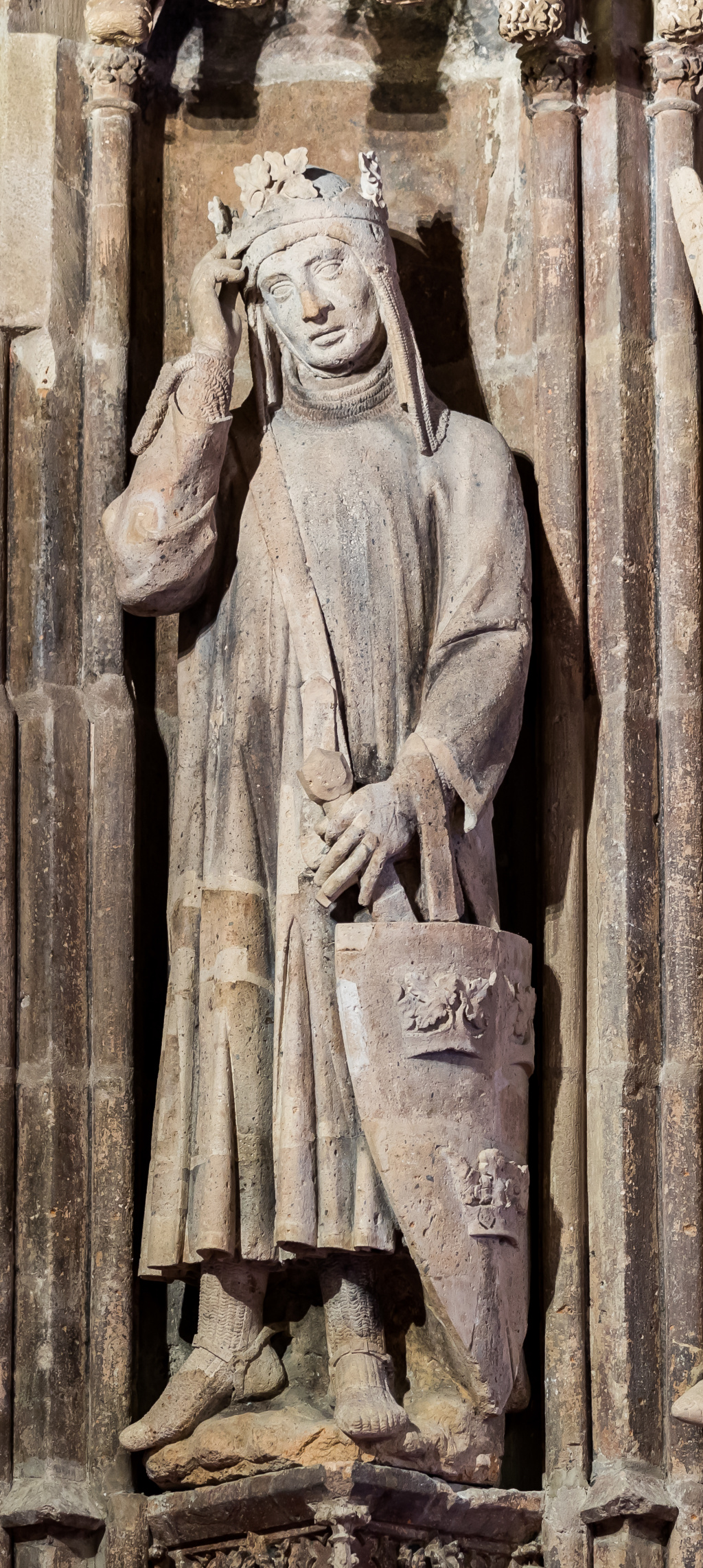

In light of Jacques de Longuyon’s literary model in his poem Les vœux du paon, the question arises as to the plastic realisation of a literary work into sculptures made of stone. While Longuyon recounts at length the glorious deeds of the nine heroes, he does not provide any detailed description of their ⟶physical appearance or attributes. However, through their battles recounted in the verses the heroes are characterised as warriors, which prompted a portrayal of weapon-wearing figures in armour. Made of stone and around 185 cm tall, the sculptures of the Nine Worthies are arrayed in a row on triangular brackets each under an octagonal baldachin.18The cited dimensions of the monuments are those provided by Fried Mühlberg. Mühlberg: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte”, 1973, 78. They have a calm stance with both legs on small mounds, the forward sections of their feet pointing outwards. The heroes are clothed in contemporary, knightly tunics and protective chain mail leggings. On top of their tunics, four of the portrayed heroes are wearing a cloak closed over their chests and pulled up behind their elbows, such that the rest of their bodies and weapons remain visible. Each of the nine heroes is depicted additionally wearing a belt draped from his hip and falling before his groin to suspend his sword. Each figure is also given a shield placed on its left side. The heroes’ faces bear no individual features and thus have no portrait-like character. Also with regard to age, no distinctive differences can be seen between the individual figures.

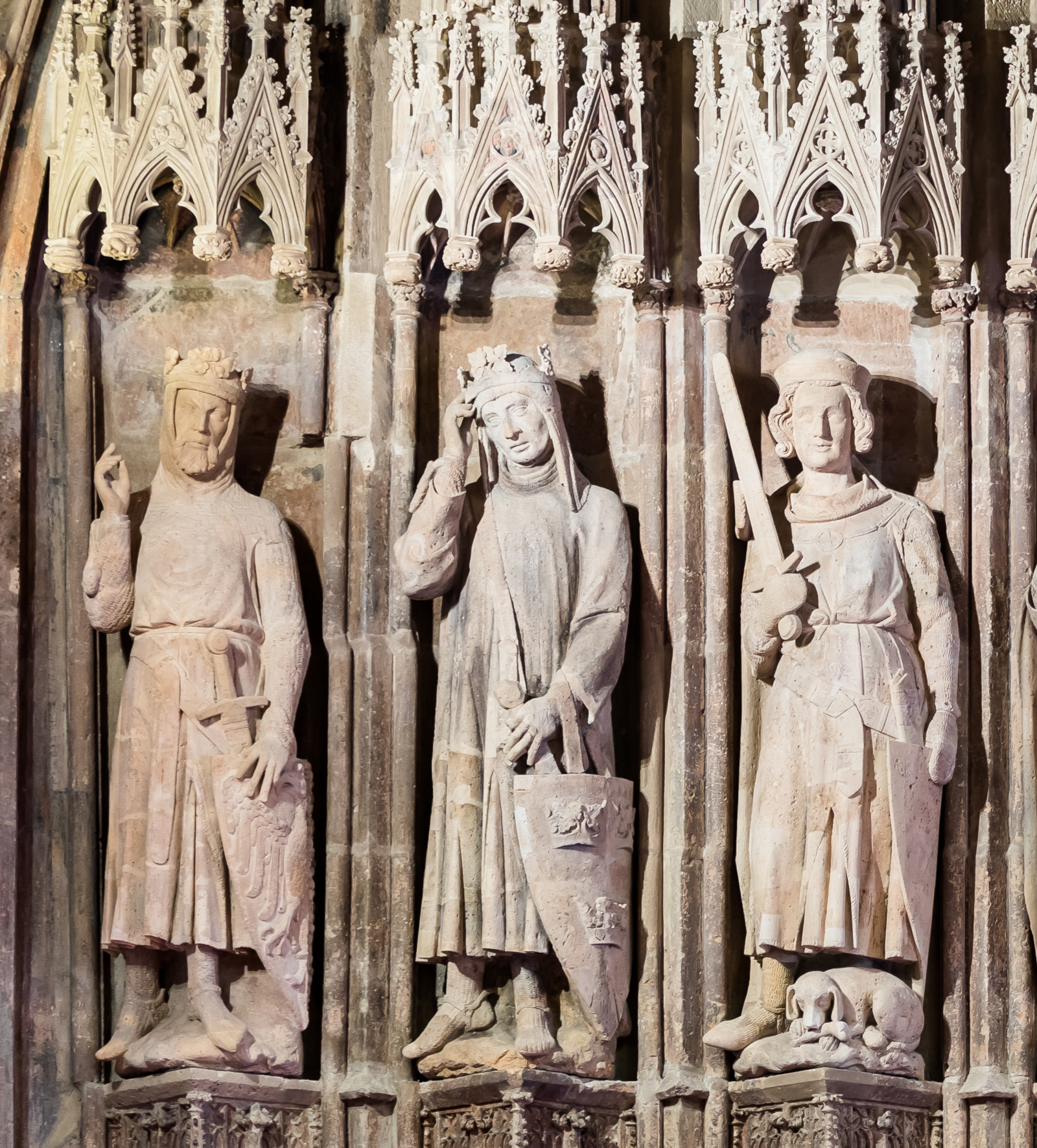

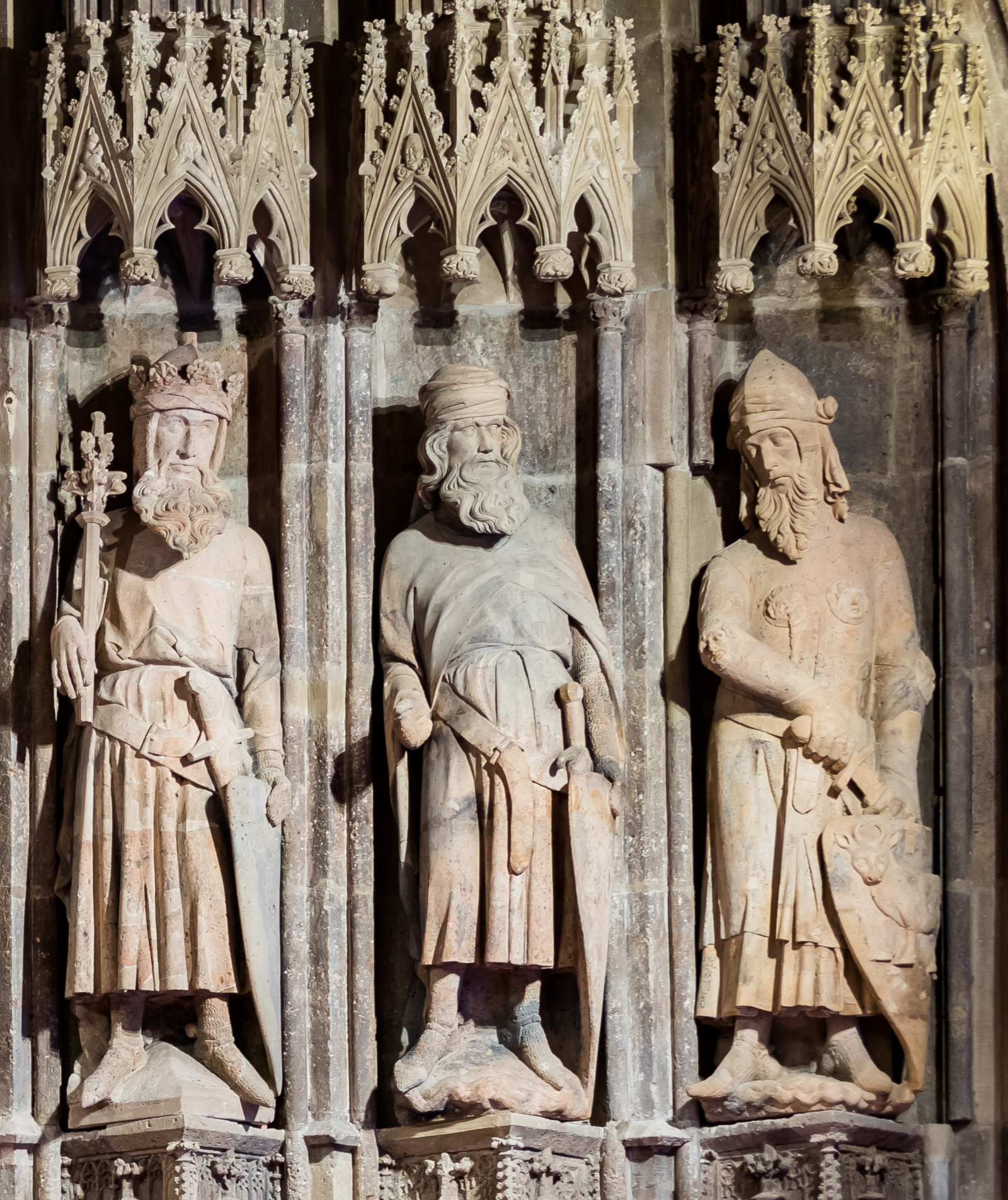

Their positioning at the south wall of the Hansasaal makes it impossible to examine them from all sides; the frontal aspect was therefore intended as the main perspective from which to view them. Standing from left to right: the three Christians Charlemagne, King Arthur and Godfrey of Bouillon (fig. 4); the three Old Testament heroes Joshua, David and Judah Maccabee (fig. 5) and the three pagan heroes Caesar, Hector and Alexander the Great (fig. 6).

Due to the uniform knightly attire, there are no distinctive differences between the individual heroes. Nevertheless, using their faces, the statues can be divided into triads according to religious affiliation: the Christian heroes differ from the Jewish and pagan trios through their clean-shaven faces, while the Jews and pagans wear full beards. The Jewish trio, for its part, is different from the others through its high pointed helmets “that call to mind the typical Jewish caps with which the Old Testament tribe was constantly characterised in the middle ages.”19Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 86. Translation by Daniel Hefflebower. In the original: “Die Kopfbedeckung der Juden besteht aus betont spitzen Helmen, die an die typischen Judenhütchen erinnern, womit im Mittelalter das alttestamentliche Volk stets charakterisiert wurde.” Contrary to Wyss’s (1957) description of the statues as having been kept in the natural colour of the stone, with only the beards and hair gilded,20Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 86. vivid colours have been recorded for the figures in a pre-World War II restoration: “They had been painted red, blue and green; their weapon adornment, hair and beards were kept in gold.”21Mühlberg: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte”, 1973, 79.

David takes a central position in the middle of the group of figures (fig. 7). The frontal positioning of his body and the particular activity emphasise him in particular within the group of heroes. With his left hand, he is bracing himself on his shield, while he has already almost entirely unsheathed his sword with a broad sweeping motion. This undaunted combat readiness distinguishes the figure of David distinctly from Joshua standing to his left (fig. 8). While Joshua is already wearing protective gloves, his sword is still hanging in its sheath on his belt affixed loosely to his hip. Joshua’s right arm is bent, and in his left hand he holds his shield with ease. His hips are shifted slightly to the right, which leaves the figure’s torso almost leaning against the left side of the niche wall. His head is turned slightly to the left with his gaze directed at a point in the distance. With the third Jewish hero, Judah Maccabee, there is another variation of the ready-for-battle demeanour (fig. 9). With his left hand, Judah is grabbing the hilt of his sword, though it is still entirely in its sheath. He is the only one among the heroes holding up his triangular shield, rounded at the top, in front of the left side of his body. His right hand is raised to his right ear, while his head is inclined slightly to the right. The figure’s gaze is directed upwards as if it were awaiting a decision from divine heights.

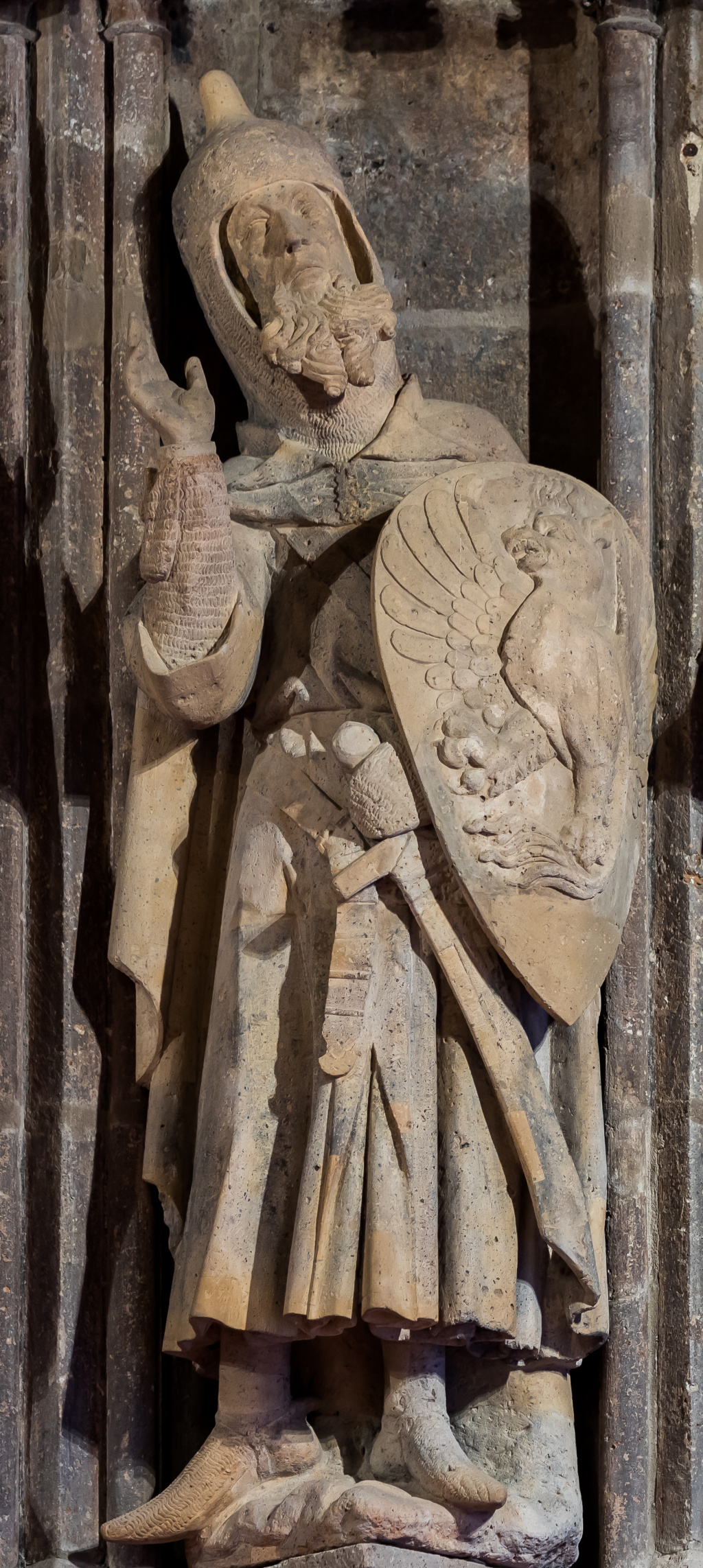

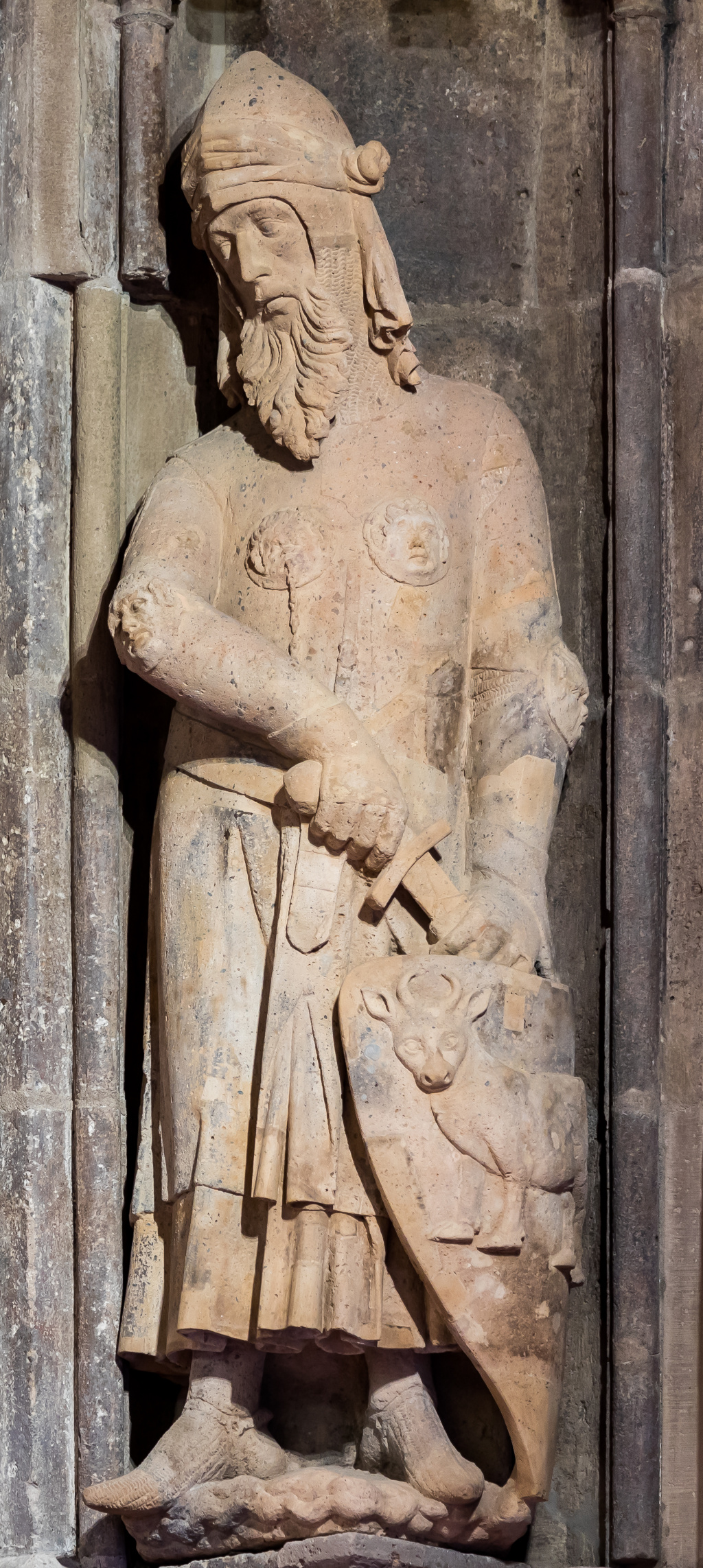

In the group of pagans (fig. 10), which stands to the right of the Jewish triad in the row of heroes, it is only Alexander the Great who is poised to seize his weapon. His left hand holds the sheath from which he with his right hand is already beginning to draw his sword. In addition to the uniformly fashioned knightly clothing of the other heroes, the figure wears a breastplate displaying the heads of Gorgons. These are to be viewed as symbols of Alexander’s successfully waged battles. On his head, which is slightly bowed to the left, Alexander wears a turban. Next to Alexander the Great stands Hector of Troy (fig. 11). The body of the sculpture is turned slightly to the left; the right hand is held at the height of the hips, while the other rests at ease on the shield. Similarly, a scarf is slung around Hector’s head, which is turned to the left. Like Joshua, Hector gazes at a point lying in the distance. The seventh figure in the group of the Neun Gute Helden is the Roman ruler Caesar (fig. 12). Among the trappings of his power, he wears a crown with leaf-shaped points and in his right hand holds a sceptre, which unambiguously marks him as a ruler. His left hand meanwhile holds the shield, just like with the rest of the heroes, on the figure’s sinistral side. His gaze is, similarly to those of Joshua and Hector, focused expectantly in the distance.

In the group of Christian heroes (fig. 13), Charlemagne is the first in the line on the left at the Hansasaal’s south wall. His right arm is raised in an admonishing gesture, while the left hand holds the shield. Like Caesar, Charlemagne also wears a crown on his head. The second figure standing in the row of heroes is King Arthur, whose left hand is closed around the hilt of his sword. With his right hand, he touches his head, on which he wears a two-leafed crown (fig. 14). His head is inclined a little to the left, which can be interpreted as a gesture of contemplation. To the right of Arthur and the left of Joshua stands Godfrey of Bouillon (fig. 15). At his feet lies a dog, a loyal companion of the hero, chewing absently on a bone. Godfrey, like the other heroes, holds the shield with his left hand. In his right hand, he holds up his sword ready for battle.

3.3. The Neun Gute Helden as conveyors of good governance

Compared to painting and tapestry, sculptural statue has, as a plastic expression of the hero, a ⟶mediality that must receive particular attention. ‘Heroic’ materials such as bronze and stone make plain the aspirations to immortalise the achieved heroic deed and shape the perceptions of the beholders through their designed permanent presence over a long period of time. The effort to plan and realise a stone monument, as in the case of Cologne’s Neun Gute Helden, correlates greatly to the notion of the heroic. The materiality of stone symbolises constancy, immutability and permanence. This symbolic power of the material can also be transferred onto the councillors’ political programme: the laws passed in the Hansasaal stand in the tradition of the nine heroes, who, as conveyors of good politics, watch over the council sessions monitorially by virtue of their exemplary deeds. By looking up at the monuments to the heroes, the beholders are reminded without fail to follow their examples.

The Neun Gute Helden did not just stand for knightly ideals such as courage and combat readiness, but also epitomised good politics. Therefore, three of the heroes – Joshua, Caesar and Hector – have been fashioned such that their gazes wander into the distance. They are expressions of contemplation and consideration, as well as reminders that any good decision is to be taken only as a result of careful reflection. Another three figures – Charlemagne, Arthur and Judah – appear to be hoping for inspiration. They caution against hastily taken decisions and advise thorough assessment. Precisely Judah Maccabee, with his gaze directed upwards and his hand at his ear, also seems to be waiting on divine counsel. The remaining three heroes – Godfrey of Bouillon, King David and Alexander the Great – show themselves ready for battle with drawn swords. They symbolise assertiveness and the power to execute political decisions purposefully and to defend concluded agreements courageously.

Through the creative intensification of larger-than-life monuments and their placement in the public‑political space of the Hansasaal, the group of heroes is enshrined to a particular degree in mediaeval society. Thus the heroes in Cologne do not just symbolise virtuous ideal figures, but enter “the sphere of justice and turn into assistant figures of the court and the judges who pass the people’s judgments on right and wrong”.22Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 87. In that function, they evolve into exemplary characters for every individual citizen of Cologne, who is expected to conduct his life within society by observing laws and rights. The impact of the hero statues is thus not limited to just the councillors but is also felt by all the city’s citizens. Every one of the Neun Gute Helden points to the exemplary virtues of thorough deliberation, consideration and assertiveness – virtues of timeless continuity and topicality that are called to mind again and again by viewing the sculptures (see e.g. fig. 16).

4. Literature review

In his 1957 article Die Neun Helden: eine ikonographische Studie published in the periodical Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte, Wyss studies the subject of the Nine Worthies and their visual portrayals.23Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957. He opens his exposition with an overview of the literary sources, then focusing on Jacques de Longuyon’s Les vœux du paon (1312) and other written French sources. Wyss identifies and discusses the particular ⟶adoration of the nine heroes in the second half of the 15th century at the Burgundian court. After iconographic comments on selected works dealing with the heroes in the French and German cultural sphere, Wyss focuses on portrayals of the Nine Worthies in Switzerland that appeared for the first time in the 15th century. The aim of Wyss’ work is to retrace the literary and visual sources of the Swiss portrayals and examine the connections to the foreign parallel phenomena.

In his 1971 book Der Topos der Nine Worthies in Literatur und bildender Kunst, Schroeder attempts to comprehensively document the topos of the Nine Worthies and to shed light on different approaches for explaining its origins and dissemination.24Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971. He refutes the controversial claim that the topos of the Nine Worthies originated in Welsh triads to then deal at length with Jacques de Longuyon’s Alexander Romance Les vœux du paon as the point of departure for the topos.25In his exposition, Schroeder follows the remarks of Paul Meyer, who already in 1883 called Longuyon’s poem the origin of the nine heroes topos. Meyer, Paul: “Les neuf preux”. In: Bulletin de la Société des anciens textes français 9 (1883), 45-54. Using a selection of examples evidencing the spread of the topos in European literature and visual arts, Schroeder is able to show convincingly that the concept spread out not just geographically, but also across ⟶genres. The topos appears for instance not just in literature, but also in tapestries, murals, stained-glass windows, sculptures, heraldry, woodcarving and metal engraving as a visual subject. Furthermore, Schroeder discusses ancillary formations to the Nine Worthies topos, the nine heroines or Nine Worthy Women and the figure of the tenth hero.26The figures of the Nine Worthy Women (neuf preuses), including Penthesilea, Tomyris and Semiramis, are all part of Greek mythology, but unlike the three male triads they do not stand for three different religions. Individual heroines come from the Amazons, and therefore proved their bravery and combat readiness in a large number of battles. Nevertheless, both Huizinga and Wyss do not consider the heroic deeds of the Amazons to be the origin of the group of heroines, rather the mediaeval need for symmetry. That necessitated a juxtaposition of the nine heroines and the nine heroes in the form of a feminine pendant. Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1969, 92. Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 104. For a comprehensive examination of the nine heroines: Sedlacek, Ingrid: Die Neuf Preuses. Heldinnen des Spätmittelalters. Marburg 1997: Jonas.

A closer examination of the Neun Gute Helden of the Hansasaal in Cologne has been made by Geis (2000) in the edited volume Köln: Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung.27Geis: “Die Neun Guten Helden”, 2000. Like with Wyss and Schroeder before him, Gies bases his exposition on Longuyon’s epic poem and links it with an analysis of the plastic rendering of the literary reference. Geis examines not just the design and apparel of the nine heroes, but also possible sources of inspiration for the sculptures. The nine heroes’ function as a model with which Cologne’s city councillors could identify formed another important emphasis in Geis’ examination of the group.

Recent research on the subject of the Nine Worthies conducted by Andrey Egorov (2018) concentrates primarily on the symbolism and function of the group of figures.28Egorov, Andrey: “Charismatic Rulers in Civic Guise: Images of the Nine Worthies in Northern European Town Halls of the 14th–16th Centuries”. In: Bedos-Rezak, Brigitte Miriam / Rust, Martha Dana (Eds.): Faces of Charisma. Image, Text, Object in Byzantium and the Medieval West. Leiden / Boston 2018: Brill, 205-239. Despite nascent secularisation, the likenesses of Christian figures were conspicuous and were intended to effect just conduct. In his extensive study, Egorov shows – using selected examples in the town halls of Cologne, Mechelen and Lüneburg – that the task of the nine heroes as role models of a good government was primarily to motivate the citizen councillors to act in equally exemplary fashion: “Prefiguring one another as types and antitypes, the Nine Worthies are meant to embody the most prominent and glorious worldly recipients of the gifts of grace in each successive period – as such, of course, they are charismatic figures in a literal sense.”29Egorov: “Charismatic Rulers in Civic Guise”, 2018, 211. Egorov also questions the selection of the figures and discusses the idea of an overwhelming charismatic allure that is inherent in them and that was also said to emanate onto their beholders.30Egorov: “Charismatic Rulers in Civic Guise”, 2018, 210.

5. Einzelnachweise

- 1Wyss, Robert: “Die neun Helden. Eine ikonographische Studie”. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 17 (1957), 73-106, 73.

- 2Höltgen, Karl Josef: “Die ‘Nine Worthies’”. In: Anglia – Zeitschrift für englische Philologie 77 (1959), 279-309, 280. Translation by Daniel Hefflebower, in the original: “Aus der Gliederung in drei Dreiergruppen gemäß den drei Religionen spricht nicht nur die Vorliebe für Zahlenspiel und -symbolik, sondern auch die alte Gewohnheit der Weltchronisten, die Geschichte in Anlehnung an die Bibel in mehrere Weltzeitalter einzuteilen.”

- 3This structuring of history into three periods derives from the epistle of the apostle Paul to the Romans in which he makes that distinction when he writes: “For sin shall not have dominion over you: for ye are not under the law, but under grace.” (Romans 6:14; The King James Bible).

- 4Even Johan Huizinga in his 1919 classic of European historiography Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen (English title: The Autumn of the Middle Ages) refers to Jacques de Longuyon’s Les vœux du paon as the first source of the nine heroes topos: “The same inseparability of knightly and Renaissance elements can be found in the cult of the Nine Worthies, ‘les neuf preux’. This group of nine heroes – three pagans, three Jews, three Christians – appears first in chivalric literature: the earliest account is found around 1312 in ‘Vœux du paon’ by Jacques de Longuyon.” Huizinga, Johan: The Autumn of the Middle Ages. Transl. by Rodney J. Payton and Ulrich Mammitzsch. Chicago 1996: The University of Chicago Press, 76.

- 5Cf. Geis, Walter: “Die Neun Guten Helden, der Kaiser und die Privilegien”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 387-413, 387.

- 6Cf. Geis: “Die Neun Guten Helden”, 2000, 387.

- 7In his 1971 exposition on the topos of the English ‘Nine Worthies’ in literature and the fine arts, Horst Schroeder points out the significance of the nine heroes in respect of a summary overview of world history. See Schroeder, Horst: Der Topos der Nine Worthies in Literatur und bildender Kunst. Göttingen 1971: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 49. According to Karl Josef Höltgen (1959), this corresponds “[…] to the personified character of mediaeval historiography to present history not as an objective sequence of events, but as the deeds and fates of outstanding personalities” (Translations by Daniel Hefflebower. In the original: “Die Abfolge der neun Figuren […] bietet eine auf Namen reduzierte Universalgeschichte und entspricht dem personalen Charakter mittelalterlicher Historiographie, Geschichte nicht als objektiven Geschehnisverlauf, sondern als Taten und Schicksale hervorragender Persönlichkeiten darzustellen.”) Höltgen cites as examples “world chronicles and annals that often begin with Adam and mark individual periods of time by one or more names […]” (“Weltchroniken und Annalen, die häufig mit Adam beginnen und einzelne Zeitabschnitte durch einen oder mehrere Namen markieren, zeigen dies Strukturprinzip”). Höltgen: “Die ‘Nine Worthies’”, 1959, 280.

- 8Geis: “Die Neun Guten Helden”, 2000, 388. Translation by Daniel Hefflebower, in the original: “Es folgt eine Sittenlehre, in welcher der Dichter die Fürsten zu einer Politik ermahnt, die dem Gemeinwohl dient, in der die Eltern zu gründlicher Unterweisung der Kinder ermuntert, die Prasser zur Mäßigung und die Dichter zur Wahrung der Moral aufgefordert werden.”

- 9Cf. Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 79.

- 10Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 79.

- 11Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 80.

- 12Dating the Neun Gute Helden sculptures is a matter of contention in scholarly literature. Bergmann and Lauer date the figures to the time around 1310 due to stylistic parallels to a find of sculpture fragments from the chancel in the Cologne Cathedral. See Bergmann, Ulrike / Lauer, Rolf: “Die Domplastik und die Kölner Skulpturen”. In: Bergmann, Ulrike / Legner, Anton (Eds.): Verschwundenes Inventarium. Der Skulpturenfund im Kölner Domchor: Cologne 1984: Schnütgen-Museum, 40-41. This conjectured period of completion however is likely too early. In his in-depth study, Geis dates the figures to the years between 1320 and 1330 based on convincing arguments. Geis: Die Neun Guten Helden, 2000, 400-401. The reference to Jacques de Longuyon’s Les vœux du paon alone is an argument against the early dating made by Bergmann and Lauer because Longuyon did not write the poem until around 1312. Moreover, the poem was written in French. It was not until Jan van Boendale’s Leken Spieghel that there was a literary example in a language that was also understood by the inhabitants of Cologne. Based on the book’s prevalence, it can be surmised that it was also known to the Cologne public. If these two literary sources are posited as the basis for the group of sculptures, then the date of their completion cannot have been until after 1312 or after the publication of the Leken Spieghel between 1325 and 1333.

- 13Cf. Mühlberg, Fried: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte des alten Rathauses zu Köln”. In: Fuchs, Peter (Ed.): Das Rathaus zu Köln. Berichte und Bilder vom Haus der Bürger in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Cologne 1973: Greven, 77-106, 78.

- 14Cf. Mühlberg: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte”, 1973, 78.

- 15Cf. Leiverkus, Yvonne: Köln. Bilder einer spätmittelalterlichen Stadt. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2005: Böhlau, 122. Leiverkus points out that Cologne’s Town Hall is mentioned as early as in the first half of the 12th century. The Town Hall stands at a place in the city steeped in history: during Roman rule, the praetorium stood at the same location. Cf. Rauch, Ivo / Täube, Dagmar / Westermann-Angerhausen, Hiltrud (Eds.): Die gute Regierung. Vorbilder der Politik im Mittelalter. Cologne 2001: Schnütgen-Museum, 7.

- 16Cf. Bellot, Christoph: “Zur Geschichte und Baugeschichte des Kölner Rathauses bis ins ausgehende 14. Jahrhundert”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 197-335, 247.

- 17Cf. Hagendorf-Nußbaum, Lucia / Nußbaum, Norbert: “Der Hansasaal”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 337-386.

- 18The cited dimensions of the monuments are those provided by Fried Mühlberg. Mühlberg: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte”, 1973, 78.

- 19Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 86. Translation by Daniel Hefflebower. In the original: “Die Kopfbedeckung der Juden besteht aus betont spitzen Helmen, die an die typischen Judenhütchen erinnern, womit im Mittelalter das alttestamentliche Volk stets charakterisiert wurde.”

- 20Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 86.

- 21Mühlberg: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte”, 1973, 79.

- 22Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 87.

- 23Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957.

- 24Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971.

- 25In his exposition, Schroeder follows the remarks of Paul Meyer, who already in 1883 called Longuyon’s poem the origin of the nine heroes topos. Meyer, Paul: “Les neuf preux”. In: Bulletin de la Société des anciens textes français 9 (1883), 45-54.

- 26The figures of the Nine Worthy Women (neuf preuses), including Penthesilea, Tomyris and Semiramis, are all part of Greek mythology, but unlike the three male triads they do not stand for three different religions. Individual heroines come from the Amazons, and therefore proved their bravery and combat readiness in a large number of battles. Nevertheless, both Huizinga and Wyss do not consider the heroic deeds of the Amazons to be the origin of the group of heroines, rather the mediaeval need for symmetry. That necessitated a juxtaposition of the nine heroines and the nine heroes in the form of a feminine pendant. Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1969, 92. Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 104. For a comprehensive examination of the nine heroines: Sedlacek, Ingrid: Die Neuf Preuses. Heldinnen des Spätmittelalters. Marburg 1997: Jonas.

- 27Geis: “Die Neun Guten Helden”, 2000.

- 28Egorov, Andrey: “Charismatic Rulers in Civic Guise: Images of the Nine Worthies in Northern European Town Halls of the 14th–16th Centuries”. In: Bedos-Rezak, Brigitte Miriam / Rust, Martha Dana (Eds.): Faces of Charisma. Image, Text, Object in Byzantium and the Medieval West. Leiden / Boston 2018: Brill, 205-239.

- 29Egorov: “Charismatic Rulers in Civic Guise”, 2018, 211.

- 30Egorov: “Charismatic Rulers in Civic Guise”, 2018, 210.

6. Selected literature

- Bellot, Christoph: “Zur Geschichte und Baugeschichte des Kölner Rathauses bis ins ausgehende 14. Jahrhundert”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 197-335.

- Bergmann, Ulrike / Lauer, Rolf: “Die Domplastik und die Kölner Skulpturen”. In: Bergmann, Ulrike / Legner, Anton (Ed.): Verschwundenes Inventarium. Der Skulpturenfund im Kölner Domchor. Cologne 1984: Schnütgen-Museum.

- Egorov, Andrey: “Charismatic Rulers in Civic Guise: Images of the Nine Worthies in Northern European Town Halls of the 14th–16th Centuries”. In: Bedos-Rezak, Brigitte Miriam / Rust, Martha Dana (Eds.): Faces of Charisma: Image, Text, Object in Byzantium and the Medieval West. Leiden / Boston 2018: Brill, 205-239.

- Geis, Walter: “Die Neun Guten Helden, der Kaiser und die Privilegien”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 387-413.

- Hagendorf-Nußbaum, Lucia / Nußbaum, Norbert: “Der Hansasaal”. In: Geis, Walter / Krings, Ulrich (Eds.): Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung. Cologne 2000: J.P. Bachem, 337-386.

- Höltgen, Karl Josef: “Die ‘Nine Worthies‘”. In: Anglia – Zeitschrift für englische Philologie 77 (1959), 279-309.

- Huizinga

- Leiverkus, Yvonne: Köln. Bilder einer spätmittelalterlichen Stadt. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2005: Böhlau.

- Meyer, Paul: “Les neuf preux”. In: Bulletin de la Société des anciens textes français 9 (1883), 45-54.

- Mühlberg, Fried: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte des alten Rathauses zu Köln”. In: Fuchs, Peter (Ed.): Das Rathaus zu Köln. Berichte und Bilder vom Haus der Bürger in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Cologne 1973: Greven, 77-106.

- Mühlberg, Fried: “Bau- und Kunstgeschichte des alten Rathauses zu Köln”. In: Fuchs, Peter (Ed.): Das Rathaus zu Köln. Berichte und Bilder vom Haus der Bürger in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Cologne 1973: Greven, 77-106.

- Schroeder, Horst: Der Topos der Nine Worthies in Literatur und bildender Kunst. Göttingen 1971: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Sedlacek, Ingrid: Die Neuf Preuses. Heldinnen des Spätmittelalters. Marburg 1997: Jonas.

- Wyss, Robert: “Die neun Helden. Eine ikonographische Studie”. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 17 (1957), 73-106.

7. List of images

- 1Die „Neun Guten Helden“, im Hansasaal des Kölner Rathauses (Gesamtansicht), 14. Jahrhundert.Quelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 2Nordseite des Hansasaals im Kölner Rathaus, nach der Sanierung (2022)Quelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2023 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 3Südseite des Hansasaals mit Skulpturen der Neun HeldenQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2013 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 4Die drei Christen, Karl der Große, König Artus und Gottfried von Bouillon (v.l.n.r.).Quelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 5Die drei alttestamentlichen Helden, Josua, David, und Judas Makkabäus (v.l.n.r.).Quelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 6Die drei heidnischen Helden, Caesar, Hektor und Alexander der Große (v.l.n.r.).Quelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 7DavidQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 8JosuaQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 9Judas MakkabäusQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 10Alexander der GroßeQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 11HektorQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 12CaesarQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 13Karl der GroßeQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 14König ArtusQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 15Gottfried von BouillonQuelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2020 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

- 16Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel besichtigt die „Neun Guten Helden“Quelle: Foto von Raimond Spekking, 2019 (via Wikimedia Commons)Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0