- Version 1.0

- published 28 June 2024

Table of content

- 1. Definition and distinction

- 2. The neuf preuses – a utopia of feminine rule?

- 2.1. Amazons and oriental women rulers: the formation of the canon in the late mediaeval period

- 2.2. Literary sources and earliest pictorial representations

- 2.3. Moral re-evaluation and integration into the chivalric-courtly ideal

- 2.4. Aesthetics and mediality

- 2.5. The neuf preuses as models of ruling and fighting women

- 3. The Nine Ladies Worthy: the structuring of the canon and its use as praise of female rulers

- 4. The Neun Gute Frauen – a system of humanist virtue heroism

- 5. The state of current scholarship and perspectives

- 6. References

- 7. Selected literature

- 8. List of images

- Citation

1. Definition and distinction

The nine heroines were a collection of figures that arose in the late Middle Ages as a counterpart to the older list of ⟶nine heroes. Like that male canon, the female figures claimed fame on the basis of their recorded ⟶deeds. Starting from France (neuf preuses), distinct traditions with a varying selection of women developed in England (Nine Worthy Women or Nine Ladies Worthy) and Germany (Neun gute Heldinnen or Neun beste Frauen). Originating in literary sources, the nine heroines form an iconographic topos, which appears in all kinds of visual ⟶media. They are commonly portrayed together with the nine heroes in illuminated manuscripts, frescoes and panel paintings, as monumental sculptures, in tapestries, on playing cards and as part of festive entrées. The conceptualisation of the female canon was subject to a considerable number of changes in its reception history. As an element of the mediaeval aristocratic lifeworld, the nine heroines served representative purposes and embodied models of feminine rule and chivalry, while their later early modern conceptualisation found its way into early humanist discourses on ⟶virtuous heroism through the inclusion of ancient and biblical heroines.

2. The neuf preuses – a utopia of feminine rule?

2.1. Amazons and oriental women rulers: the formation of the canon in the late mediaeval period

The female canon known as the neuf preuses, which formed in France in the second half of the 14th century, consisted solely of women from ancient mythology and history who through their achievements had distinguished themselves as outstanding rulers or warriors (French ‘prouesse’ ~ prowess, heroic deed). In contrast to the more frequently portrayed nine heroes (neuf preux), which arose 70 to 80 years earlier, the selection of individuals in the female canon varies, which – together with individual figures’ only negligible renown and exoticism – led to early scholarship deeming the canon to be an arbitrarily assembled medley.1Huizinga, Johan: Herbst des Mittelalters. Studien über Lebens- und Geistesformen des 14. und 15. Jahrhunderts in Frankreich und in den Niederlanden. Stuttgart 1987: Kröner [First edition Munich 1924], 74; Wyss, Robert L.: “Die neun Helden. Eine ikonographische Studie”. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 17 (1957), 73-106, 74-75; Sedlacek, Ingrid: Die Neuf Preuses. Heldinnen des Spätmittelalters. Marburg 1997: Jonas, 10-11. Nevertheless, there were figures who came to appear consistently: among the women originating from the Orient, these were Semiramis, Teuta, Tomyris and Deipyle, most of whom were prominent rulers. The warrior Amazons who frequently appeared were Sinope, Hippolyta, Melanippe, Lampedo and Penthesilea.2The figures listed here correspond to the selection in the chivalric romance Le chevalier errant, which was influential for the formation of the canon. Other textual and visual sources may have different individual figures. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 11; Mamerot, Sébastien / Salamon, Anne (Eds.): Le traictié des neuf preues. Geneva 2016: Droz, LXVIII, LXXXIX. This constancy made the canon highly recognisable as such.

Although Huizinga posited that the neuf preuses were the product of a late mediaeval need for symmetry, the general observation has been made that the female canon, in view of its internal system, did not parallel the male one.3Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1987, 74; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 74-75; Schroeder, Horst: Der Topos der Nine Worthies in Literatur und bildender Kunst. Göttingen 1971: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 168, 172. Instead of the separation into three triads with different religious associations – three pagans, three Jews and three Christians – as done in the male pendant, the female group shows no comparable internal structure that alludes to the progression of world and salvation history through its ‘succession’. The lacking systematicity and meagre historical range of the neuf preuses, who come entirely from ancient history and mythology, are inconsistent with any aspiration of deriving a female ruler ideal applicable to the present.4Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 15, 99, 120-121; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, CXVIII; Wörner, Ulrike: Die Dame im Spiel. Spielkarten als Indikatoren des Wandels von Geschlechterbildern und Geschlechterverhältnissen an der Schwelle zur Frühen Neuzeit. Münster 2010: Waxmann, 220. Likewise, their function as everyday practical or moral role models for readers and viewers in the late Middle Ages has been questioned since the pagan personalities, which were deemed barbarians in ancient sources, acted according to a value system different from the Christian one. The semi-mythical realm of the Amazons was projected by ancient authors outside of the known cultural space and was characterised by the inversion of customs of the known Greek social order. Like the oriental rulers Semiramis and Tomyris, the Amazons were presented as monstrous, i.e. entirely uncivilised, beings whose actions followed solely their natural compulsiveness and who secured their rule in particular through ⟶acts of violence against male contemporaries. Incest, sexual permissiveness, a disregard for the law, infanticide and revenge killings were associated with the biographies of the neuf preuses. In consequence, they were notoriously disparaged on moral grounds starting in ancient literature and all the way up to Boccaccio’s De claris mulieribus, even though their qualities as rulers and warriors were praised emphatically and they were described as the men’s equals.5Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 33-38; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXXIII. For more on the reception history of the Amazons, see Kroll, Renate: “Amazone”. In: Kroll, Renate (Ed.): Metzler Lexikon Gender Studies. Geschlechterforschung. Ansätze – Personen – Grundbegriffe. Stuttgart 2002: Metzler, 8; Kroll, Renate: “Die Amazone zwischen Wunsch- und Schreckbild. Amazonomanie in der frühen Neuzeit”. In: Garber, Klaus et al. (Eds.): Erfahrung und Deutung von Krieg und Frieden. Religion – Geschlechter – Natur und Kultur. Munich 2001: Wilhelm Fink, 521-537; Dlugaiczyk, Martina: “‘Pax Armata’: Amazonen als Sinnbilder für Tugend und Laster – Krieg und Frieden. Ein Blick in die Niederlande”. In: Garber, Klaus et al. (Eds.): Erfahrung und Deutung von Krieg und Frieden. Religion – Geschlechter – Natur und Kultur. Munich 2001: Wilhelm Fink, 539-567.

2.2. Literary sources and earliest pictorial representations

Therefore, it is not considered very plausible to approach the ancient sources directly as the basis of the mediaeval pictorial tradition.6Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 39. Instead, the reception of the ancient material in mediaeval literature forms the background to or even the origin of this visual canon of individuals. To date, no consensus has been reached on identifying that literary source that formed the canon. Contrary to the earlier assumption that the female canon had been formed by Eustache Deschamps in his ballad Il est temps de faire la paix (1389–1396) as the counterpart to the male canon,7This view is also taken by Raynaud, Gaston: Oeuvres complètes de Eustache Deschamps XI. Paris 1903: Librairie de Firmin Didot et Cie, 225-227; Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1987 (1924), 74; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 75. most scholars now favour the earlier Livre de Leësce by Jean Le Fèvre (published between 1373 and 1387) as the oldest written source on the neuf preuses.8Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 47; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXI; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 169-171. This work was a panegyric to women that arose explicitly as a rebuttal to the misogynistic satire Lamentationes de Matheolus (1291). Around 1370, Jean Le Fèvre had translated the misogynistic work of poetry by Mathieu de Boulogne into French, which led to the text’s wide reception. Fèvre’s counter-portrayal, which he wrote roughly one decade later, seized on the misogynistic arguments of the Lamentationes in order to refute them using the Scholastic method of proposition and counter-proposition.9Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 53. At the same time, the Livre de Leësce presents a large number of virtuous women, including the neuf preuses. They are described as heroic (preuses), and both their virtuousness and their bravery are deemed superior to the qualities of the men.10“Certes, a parler de prouesce, / Propose ma dame Leesce / Que les femelles sont plus preuses, / Plus vaillans et plus vertueuses / Que les masles ne furent oncques.” Quoted according to Hamel, A.-G. van: Les Lamentations de Matheolus et le Livre de Leësce de Jehan le Fèvre. Vol. 2. Paris 1905: Librairie Émile Bouillon, lines 3528-3532. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 54; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXX. A high-ranking female patron has been suspected of being the driving force behind Fèvre’s subsequent, seemingly contradictory self-correction.11A miniature placed before the text of an early illuminated copy (ca. 1400) that arguably shows Matheolus asking for forgiveness before a queen and her court has led some to speculate whether the patron was one of the French queens from that time period, namely Jeanne de Bourbon or Isabeau of Bavaria. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. fr. 24312, fol. 79. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 54-55.

Although even earlier and more popular textual sources were assumed to be the setting of the formation of canon,12Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 55; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 171. the selection of the neuf preuses in the Livre de Leësce had gained a certain level of authority. The portrayal of the nine heroines on a full-page miniature in the 1394 allegorical chivalric romance Le chevalier errant by Thomas III of Saluzzo shows the same collection of individuals in a baldachin-like, courtly decorated architectural frame that presumably represents the palace of Fortuna, in which Saluzzo’s wandering knight encounters the enthroned heroines and learns of the history of their lives (fig. 1).13Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 56, 78; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 75.

The neuf preuses in the citadel Coucy’s Salle des Preuses in Picardy can be dated even earlier, although they are no longer found in situ. Arrayed in a single row, the colossal figures adorned the fireplace of the room that, based on its name ‘paille’ (Latin ‘pallium’ = baldachin), was used as a throne room.14The castle, greatly damaged through war today, was built in the first half of the 13th century by Enguerrand III de Coucy, who traced his genealogy back to Hercules (Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 65). See Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 190. The women selected and the coats of arms portrayed in the collection created by sculptor Jean de Cambrai between 1385 and 1387 are identical with the miniature in Le chevalier errant.15Today, the collection survives only in an engraving and a drawing by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (Les plus excellents bastiments de France) and a reconstruction drawing by Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc that is based on them. Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 58-61. A comparable project that included the preuses as monumental sculptures in the citadel architecture was launched by Louis I, Duke of Orléans, in ca. 1400: he had the outer walls of his castle La Ferté-Milon (Aisne) decorated with larger-than-life heroine figures.16The three-dimensional sculptures were placed in tower niches and formed a ring of female warrior protectors around the entire fortifications. The sculptures are roughly 2.50 meters tall, but are in very poor condition today. Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 81-82, 86-87, 89-90. As a counterpart, the Duke of Orléans decorated his castle Pierrefonds with larger-than-life figures of the preux, of which two survive in fragments today. See Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 190.

The consolidation of the canon of the nine heroines was promoted in the arts and in literature by patrons who also supported the defence of women and the portrayal of their virtues in other ways. The Duke of Orléans for instance was an important benefactor of Christine de Pizan, who in 1401 addressed the second part of Le Roman de la Rose in the Querelle and in 1405 finalised Le livre de la Cité des Dames.17Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 90. Like Le Livre de Leësce, Pizan’s work aims to construct a historiography based on female actors to counter the misogynistic diatribes widely prevalent in mediaeval literature.18Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 91. Saying good or bad about women was a literary banality in both the Middle Ages and antiquity. Instead of developing a distinct and differentiated stance, mediaeval authors invariably identified themselves quite radically with either the one or the other stance. For more on this, see Meyer, Paul: “Plaidoyer en faveur des femmes”. In: Romania 6 (1877), 499-503, 499. Pizan begins her history of the world with the preuse Semiramis and describes seven of the familiar neuf preuses in an extensive catalogue of women with exceptional talents and virtues that included even her contemporaries. She presented a lavishly illuminated copy of the manuscript to the queen of France, Isabeau of Bavaria, with whom she maintained a close personal relationship.19Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 94-95, 98; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 195-196. Boccaccio’s collection of biographies De claris mulieribus (between 1360–1375) undoubtedly served as Pizan’s source of inspiration, even though the Italian poet largely reduced the women he was presenting to their role as virtuous individuals and included only few women who held positions of power or were militarily active. In the tradition of the ancient authors, Boccaccio portrayed the latter (Semiramis, most of all) as moral counterexamples, as they violated the general canon of virtues by violating sexual norms.20Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 196. Translated into French by 1401, Boccaccio’s anthology likewise included seven of the neuf preuses. Although there have been repeated discussions on whether or not this work was a potential basis for the formation of the canon, there have also been doubts because it disparages precisely the martial personalities for having that function.21Sedlacek considers Schroeder’s proposal of assuming Boccaccio as the source (Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 179; also Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 214) to be implausible. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 47; also Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXIII. Sedlacek, however, has proposed the Histoire ancienne jusqu’à César as another possible early reference. Written in 1210 and describing eight of the nine heroines, the world history Histoire ancienne presents a compilation of ancient and biblical texts in the fashion of a salvation history and was a quite widely disseminated book primarily in the 14th century. The positive portrayal of the Amazons’ martial qualities in line with the mediaeval chivalric ideal, particularly the emphasis of their bravery, leaves the work seeming like a convincing reference for the formation of the neuf preuses canon in the second half of the 14th century.22See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 47, 51; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXIV.

2.3. Moral re-evaluation and integration into the chivalric-courtly ideal

The Histoire ancienne characterises the Amazons as brave masters of weaponry and the art of war (moult chevalereuse) who had an impressively noble disposition (prouesce). The negative connotations that were familiar from the ancient texts were not included in the courtly adaptations of ancient material. Instead, the figure of the Amazon was morally re-assessed and adapted to align with the chivalric ideal of the period.23Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 39, 96. This modification was explained in view of France’s mediaeval historiography, which was already cultivating the myth of the Trojan origin of the French monarchy in the 7th century. In 1274, the Trojan ancestry of the French was incorporated into the Chroniques de France, written at the cloister Saint-Denis. Emphasised particularly in the 14th century, this origin story gave the image of the Amazons fighting on the side of the Trojans, or – more generally – the image of the fighting woman, a positive connotation in the French tradition.24Regarding France’s Trojan origin, see Hartwig: Einführung in die französische Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft, 130-131. Regarding the pro-Trojan stance in the French roman antique, see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 41, 43, 49. Like the French royal dynasty, the Burgundian dukes traced their origins back to Troy. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 109. It was the mediaeval versions of the Alexander Romance and the Roman de Troie (1155–1160) by Benoît de Sainte Maure in particular that conceptualised a striking model of feminine chivalry using the example of the Amazons.25For more on the Amazons in the Alexander Romance by Alexandre de Paris (after 1180) and in the Roman de Troie, see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 40-42, 113. Their martial abilities, superior to those of men, are celebrated just like their outer appearance, marked by overwhelming beauty and magnificent accoutrement (fig. 2). In addition, their noble conduct, which was consistent with the ideal of the courtly woman, is foregrounded, and their procreation norms described by ancient authors are adapted to the notions of chivalric-courtly love. In contrast to their sexual licentiousness, which had been described until that time, the Amazons were now celebrated as an allegory of a chaste life. Because the Amazons, according to the mediaeval notion, prioritised the military campaign to defend their own realm over procreation, they were cited by Christian authors in the 13th century as role models for the maintenance of marital fidelity during the absence of the spouse away at war. Similar to the fighting spirit and boldness of the Amazons, the unattended women were to defend their chastity.26Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 43-44.

As the Amazons were adapted to courtly culture, they were established as the paragon of the femmechevalier – the feminine chivalric ideal. The model of the courtly woman knight was uniquely cultivated in the chivalric orders of the 14th and 15th centuries, some of which (e.g. the notable English Order of the Garter or the Ordre de la Couronne founded by Enguerrand de Coucy) admitted select female members from among the royal families and high nobility. Just like the men, the female members had to follow a code of conduct devised for them that encompassed virtues such as bravery, heroism, loyalty, boldness, courtesy, and generosity (vaillans, preux, loyaulx et hardiz; the term chevaleresse was coined in the Ordre de l’Hermine).27Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 44, 66-70. See also Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXXII. Salamon associates the appearance of feminine chivalry with the crisis of masculinity that resulted from the failure of chivalry at the military level. The neuf preuses, the canon of which was formed during the same period in which the chivalric orders saw their greatest female membership and late mediaeval chivalry experienced a revival, offered an illustration of these exemplary ⟶qualities. The heroines were portrayed in armorials in the form of their heraldic symbols or, like in Petit armorial équestre de la Toison d’Or (before 1467), as full-figure, coloured pen-and-ink drawings showing the preuses free from their earlier martiality and completely adapted to the tastes of the time and the chivalric ideal (fig. 3).28Sedlacek believes that the appearance of the preuses during festive entrée parades is reflected in the drawings since they did not display any armour at the processions, but instead luxurious clothing and ornately painted coats of arms. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 72-73; see also Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 82; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 194. Schroeder cites a number of examples of conventional armorials in which the preuses are represented. In parallel to the general trend in knighthood from the art of war to the courtly art of life, in the 15th century, the martial element receded distinctly while the courtly element was underlined in the portrayals of the preuses.

2.4. Aesthetics and mediality

As Sedlacek has explained, the virtue portrayals of armed women in Romanesque and later Gothic art served as an iconographic point of reference for the neuf preuses. Since portrayals of historical female warriors could hardly be found in mediaeval art, feminine allegories of virtues, like those in the illustrations of the Psychomachia or the sculpture programmes of Romanesque churches, offered an aesthetic repository of forms of expression that ascribed positive qualities to the figure of the fighting woman.29 Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 22, 30. With the exception of Fortitudo and Iustitia, the further iconographical development of the armament and armour of feminine virtue allegories was reduced, and the actively fighting females were transformed into enthroned figures. This yielded numerous starting points for the portrayal of the nine heroines.30For more on combined portrayals of Fortitudo and figures of the nine heroines, see Bautz, Michaela: “Fortitudo”. In: Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte. Vol. X (2004), cols. 225-271. Online at: http://www.rdklabor.de/w/?oldid=99979 (version dated 21.08.2018, last accessed 10.12.2019). In particular, courtly feminine clothing combined with martial armour as well as sitting poses of triumph and visibly presented weapons are recurring motifs with the neuf preuses. The latter mark them as victorious warriors, while elegant clothing in the fashion of the relevant time period and weapons carried with them drew attention to their aristocratic ancestry.31Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 16, 61-63.

A later manifestation of the heroine canon originating between 1411 and 1440 are the murals of the Sala baronale at the Castello della Manta in Piedmont (fig. 4). They were commissioned by Valerano del Vasto, the son of Thomas III of Saluzzo. The aesthetic developed in the frescoes correlates to the literary descriptions of the heroines that focus on the details of their clothing and armament and to their manifestations in other artistic media, such as tapestries and ceremonial entrée processions.32Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 100-105; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 80.

It is conspicuous that the decorative aspect and the visual appeal of the heroines, which has been enhanced through fanciful clothing, were emphasised in those media in particular. Of the numerous tapestries produced for the French nobility in the late 14th and 15th centuries portraying the preuses, none have survived.33 Only mentions of tapestries created in France (a select few in England) with portrayals of the neuf preuses survive in inventories and invoices. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 109, 113, 115; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 78-79; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 184. However, there are a number of descriptions of and references to the preuses’ role in sovereign pageants and processions. Together with the preux, they accompanied on horseback King Henry VI of England as he entered Paris in November 1431, appearing in his immediate vicinity armed with their weapons and coats of arms.34Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 118; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 196; Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1987 (1924), 74; Wright, Celeste Turner: “The Elizabethan Female Worthies”. In: Studies in Philology 43 (1946), 628-643, 628. For the procession in honour of Marie d’Albret, wife of Charles de Bourgogne, as she entered Nevers in April 1458, it is recorded that the magnificent clothing were created according to templates provided by tapestries. In particular, the tunics, the horses’ saddlecloths, the coats of arms and the elaborately designed headdresses made of foliage and tinsel were all painted to be à la preuse and preux.35Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 119; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 198.

The portrayal of the preuses as semi-mythical figures strangely clothed according to the custom of their exotic countries of origin demonstrates their late mediaeval reception as legendary, mysterious beings, a reception that continued to be maintained in early modern contexts.36Regarding the appearances of imaginatively clothed preux and preuses at fairs, see Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 199; Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 127-128. Inigo Jones’s rendering of figures of the English Nine Ladies Worthy in his drawings for The Masque of Queens (1609) as exotic roles in fanciful clothing in particular shows the great allure of the playful identification of the woman ruler and her female retinue with the heroines.37Waith, Eugene M.: “Heywood’s Women Worthies”. In: Burns, Norman T. / Reagan, Christopher J. (Eds.): Concepts of the Hero in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. New York 1975: State University of New York Press, 222-238, 235-236; Wright: “The Elizabethan Female Worthies”, 1946, 629. At the same time, the inclusion of a number of preuses as ‘queens’ in French playing cards of the 15th and 16th centuries speaks to their popularity and complete integration into the aristocratic lifeworld.38Argia regularly appeared as the queen of clubs. A French playing card deck from the second half of the 15th century contains the complete series of preux and preuses. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 117; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 201; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 213, 215; Waith: “Heywood’s Women Worthies”, 1975, 233.

2.5. The neuf preuses as models of ruling and fighting women

Despite the recognition of noble women by the canon of the neuf preuses, it – unlike the male canon – was not ascribed any legitimising function in how female rulers used to stage their claim to power. Since exclusively pagan female rulers and warriors are represented, and no Christian ones, they were unable to gain any direct, identity-creating paradigmatic qualities for the present. As it was practiced starting in the 14th century in interpretation of the Salic Law (Lex salica), the exclusion of women from succession formed the historico-political backdrop to the formation of the neuf preuses canon. Against it, female rulers were conceivable only as semi-mythical, ahistorical ‘artificial characters’, such as the Amazons, or as female rulers who illegitimately came to power after the death of their spouses, such as Semiramis and the Scythian Queen Tomyris.39Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 107; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 220. Regarding the Lex salica, see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 121, 130. Therefore, the moment of the accession to power after the death of the husband or – in the matriarchal realms of the Amazons – of the mother constituted a significant element in the lives of the heroines, whose status could only be that of unmarried women or widows.40Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, CXII.

However, the absence of male rulers was not enough to establish the preuses’ rule: the decisive element for the enduring stability of their positions of power was their trial in battle and affairs of state. Semiramis, who illegitimately assumed power after the early death of her husband Ninus on behalf of her son Ninyas, who was still a child, disguised herself in order to pose as her son before her army. Not until after a phase of great military successes that brought her respect and authority did she dare to shed her disguise and reign openly as a woman. Her enormous territorial conquests and the prosperity to which she led her empire surpassed her husband’s successes and secured glory for herself in posterity.41Sedlacek provides an overview of the recorded legends concerning Semiramis, in particular those recounted by Diodorus and Justin. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 31-32. According to Salamon, Semiramis is the first woman to put on men’s clothing and go to war. See Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, 5. An episode recounted by Boccaccio illustrates that she – similar to the Amazons – prioritised her military discipline over her attention to feminine spheres of life (source 1).

“One day, when all was peaceful and she was enjoying a leisurely rest, she was combing her hair with the dexterity of her sex. Surrounded by her maids, she was plaiting it into braids according to native custom. Her hair was not yet half finished when she was told that Babylon had defected to her stepson. So distressed was Semiramis by this news that she threw aside her comb and instantly rose in anger from her womanly pursuits, took up arms, and led her troops to a siege of the powerful city. She did not finish arranging her hair until she had forced the surrender of that mighty place, weakened by a long blockade, and brought it back under her power by force of arms. A huge bronze statue of a woman with her hair braided on one side and loose on the other stood in Babylon for a long time as witness to this brave deed.”

Source: Boccaccio, Giovanni: Famous Women [De mulieribus claris]. Edited and translated by Virginia Brown. Cambridge, MA/London 2001: Harvard University Press, 21.

Explanation: The portrayal tradition reproduced by Boccaccio and purportedly established by Semiramis herself was incorporated into the iconography of the neuf preuses: even the early miniature found in the Chevalier errant shows Semiramis’s undone and plaited coiffure beneath a high hoop crown (fig. 1). In her portrayal at Castello della Manta, Semiramis combs the undone, long flowing part of her hair and is looking keenly to the side, as if the moment were being portrayed in which the message of Trebeta’s invasion reaches her (fig. 4). At the same time, the episode is reproduced in the titulus installed beneath the figure. (See Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 219.) Focalised in that way, Semiramis’s two-part coiffure acquires a significance that goes beyond this episode: it symbolises Semiramis’s Janus-faced gender identity, which, in view of extraneous necessity, gives priority to showing masculine qualities and returns to behaving in ways recognised to be feminine when the external circumstances allow. As unique qualities, the fluidity and ambivalence of Semiramis’s self-understanding, which enables her to act in both male- and female-connoted spheres of activity, are the basis for her heroism and also define her further characterisation. While her military achievements continued to be heroized, her femininely connoted side was widely caricatured in a negative light by mediaeval authors, particularly by linking her with the vice lussuria: Boccaccio labelled Semiramis’s introduction of polygamy and the accusation of an incestuous relationship with her son as a blemish on her otherwise exemplary biography. For Petrarch, although she is bold, she is also wicked and entangled in her compulsiveness. Dante situates the female ruler in the inferno (Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 33). Although there is a clear parallel to the notorious seductiveness of male heroes, Semiramis’s sexuality greatly served historiography as a target of moral rebuke, while in visual portrayals the ambivalence of disciplined rule and lussuria appear without any indication of moral disparagement. Instead, that ambivalence is used as a means of visualising her androgyny. Thus, Semiramis is aligned with the hero type common since classical antiquity that was neither exclusively idealised nor demonised. Instead, the type acted as the master of its own dual nature in engaging with its inner contradictions and the adversities of its fate.

It stands to reason that the neuf preuses could serve as a model of exemplary female governance for women rulers or wives of rulers who unexpectedly assumed regency, like Isabeau of Bavaria, the suspected patron of the Livre de Leësce, who increasingly took over the affairs of state as Charles VI’s insanity progressed.42Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 194. Written by Sébastien Mamerot in the 1460s and considered one of the late works in the portrayal tradition of the neuf preuses, the Histoire et faits des Neuf preux et des Neuf preues (sic) emphasises in particular, in addition to their martial achievements, the qualities of the preuses as regents and lawgivers, who returned from their campaigns to find their countries in peace and prosperity and with functioning orders. This perspective allowed the neuf preuses to be established as the female ruler ideal that self-portrayals of women regents and aristocrats of the following centuries drew upon in the form of a portrait as an Amazon – frequently with armour worn under their clothing.43Regarding the positive portrayal of the regencies of the preuses, see Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, CXVI-CXVIII. Among those who portrayed themselves as androgynous Amazons were for example Elizabeth I, Anne of Austria, and even male rulers such as Francis I. See Kroll: “Amazone”, 2002, 8. Even allegorical portraits, such as that of Maria de Medici as Bellona, can be placed in this category.

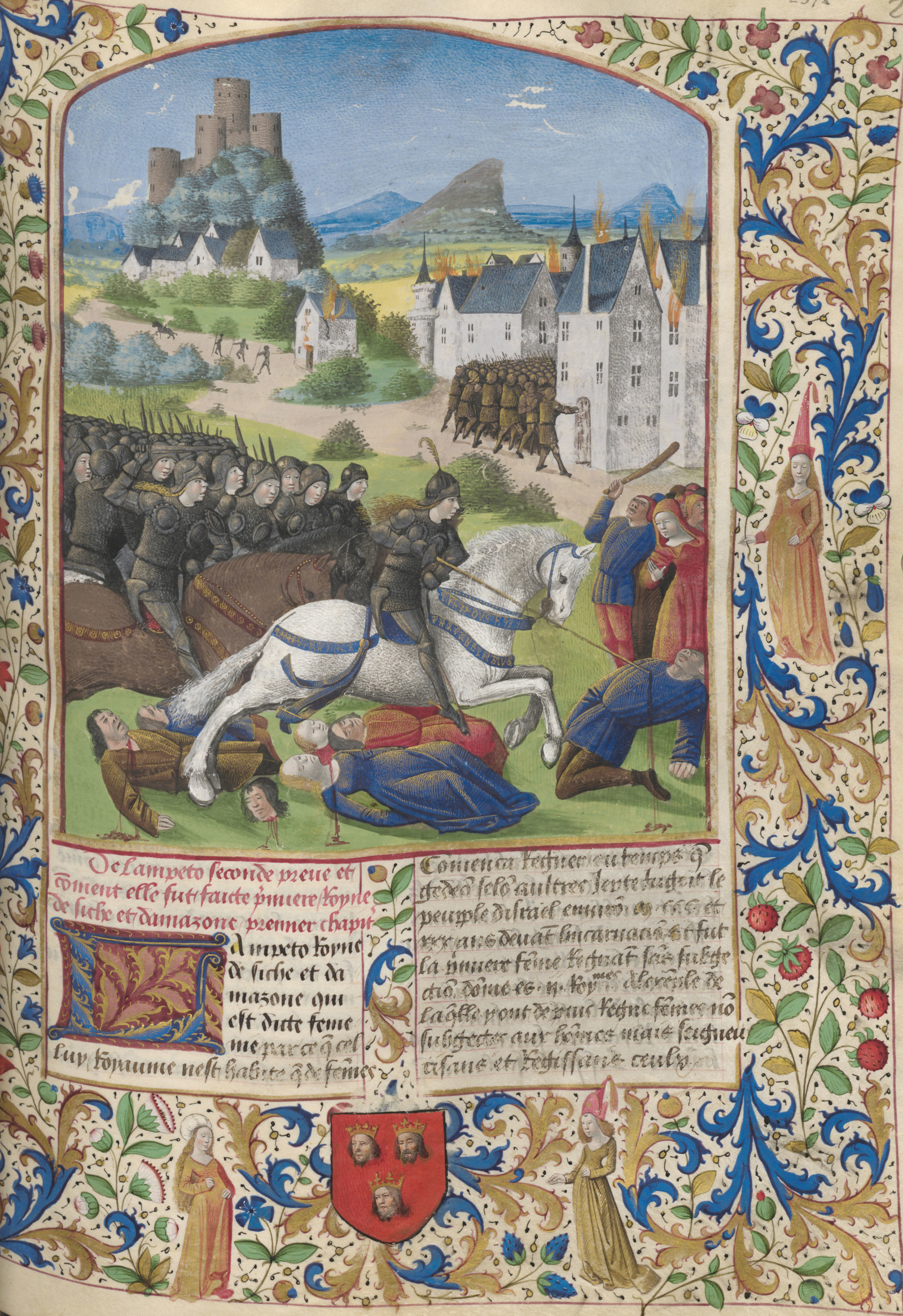

Mamerot’s benefactor, the French noble Louis de Laval, had both the male and female canons expanded to each comprise a tenth personality from the recent past who was celebrated as a ⟶hero(ine). For the preux, he selected the famous military leader and connétable Bertrand de Guesclin (1320–1380); for the female canon, he chose the much more recent, French national heroine and saint Joan of Arc (1412–1431), who had only been rehabilitated a few years prior to the publication of Mamerot’s Histoire.44The lives of the two have not survived. It is possible that they were removed at a later date. An announcement in the prologue attests that they were indeed originally part of the work. See Lecourt, Marcel: “Notice sur l’histoire des neuf preux et des neuf preues de Sébastien Mamerot”. In: Romania 37 (1908), 529-537. See also Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1987 (1924), 75; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 75; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, XCV; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 223, 226; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 219-223. Schroeder mentions a tenth preuse portrayed in the tapestry. The miniatures in the illuminated luxury volume return to a noticeably martial representation of the neuf preuses, into which Joan of Arc fit seamlessly as an armed virgin (fig. 5).45Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 117, 131; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 217. Besides the prominence that the two attained through their achievements in the Hundred Years’ War, Laval’s selection can be explained by his personal ties to Guesclin, who was his step-grandfather, and the fact that his brothers fought together with Joan and greatly adored her. A letter records the strong impression that the ‘maid’ had on the brothers. See Lecourt: “Notice sur l’histoire”, 1908, 534-536. Regarding the miniatures, which were created in a collaborative project between Jean Colombe and an anonymous painter, see Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 81; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LII. Christine de Pizan’s euphoric panegyric Le Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc (1429), written in homage to the ‘maid of Orléans’ while she was still alive, and the laudatory verses of Antoine Astesan draw comparisons with ancient and biblical heroines.46“Hester, Judith et Delbora / Qui furent dames de grant pris, / Par lesqueles Dieu restora / Son peuple qui fort estoit pris, / Et d’autres plusieurs qu’ay appris / Qui furent preuses, n’y ot celle ; / Mais miracles en a porpris [?] / Plus a fait par ceste Pucelle.” Christine de Pizan’s panegyric quoted according to Quicherat, Jules: Procès de condamnation et de réhabilitation de Jeanne d’Arc dite la Pucelle. Vol. V. Paris 1849: Jules Renouard et cie, 12 (28); regarding Antonius Astesanus, see Molinier, Auguste (Ed.): Les Sources de l’histoire de France depuis les origines jusqu’en 1815. Part 1: Des origines aux guerres d’Italie (1494). Paris 1903: Alphonse Picard et fils, art. 4394, 4487. Berriat-Saint-Prix, M.: Jeanne d’Arc ou coup-d’oeil sur les révolutions de France […]. Paris 1817: Pillet, 305: “Tantus erat pudor huic et tanta modestia ut ipsa / Esse videretur mirae Lucrecia famae.” See Lecourt: “Notice sur l’histoire”, 1908, 535; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 175-177; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 223, 228; Rivera Garretas, María-Milagros: Orte und Worte von Frauen. Eine feministische Spurensuche im europäischen Mittelalter. Vienna 1993: Wiener Frauenverlag, 213-214; Warner, Marina: Monuments & Maidens. The Allegory of the Female Form. London 1985: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 164-165. For general remarks relating to Joan of Arc, see Warner, Marina: Joan of Arc. The Image of Female Heroism. London 1981: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Salamon points out the fact that Mamerot’s work was published around the same time as Joan of Arc’s rehabilitation (Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, XCVI). Through that association, the fame of the unhistorical preuses experienced a revival and confirmation that circumvented the previous ahistorical concept of the female canon and now used it to specially acknowledge the achievements of a contemporary personality. Despite the notoriety of comparable fighting women celebrated as heroines, like Isabel of Conches (1070–1100), who fought as a knight, this opening up of the canon for contemporary heroines was a singular occurrence, even though the panegyric comparison of the preuses with famous women of the time became common.47On the comparison of Isabel de Conches-Tosny with the preuses, see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 46. Christine de Pizan names women from the Old Testament besides contemporary rulers (see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 91-92). At the end of the 15th century, the narrowly defined mediaeval canon of the neuf preuses finally lost its significance, and its heroines such as Joan of Arc turned up in the quantitatively more generous tradition of the femmes fortes starting in the 17th century.

3. The Nine Ladies Worthy: the structuring of the canon and its use as praise of female rulers

The English tradition of the Nine Ladies Worthy structures the nine heroines consistent with the male canon into three triads assigned to the different religions. The selection of figures in the few surviving visual and textual sources is marked by variability: the triad of pagan women comprises familiar figures of the neuf preuses, such as Penthesilea, Tomyris, and Semiramis, but they are combined freely with new figures, like the British Queen Boudica, who led a revolt against the Roman occupation of the country, or the goddesses Artemis and Minerva.48Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 128; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 229; Wright: “The Elizabethan Female Worthies”, 1946, 628. The substantive emphasis remains – consistent with the neuf preuses – on feminine warriorhood, that is, the ideal of the virago, whose combativeness is expressed in particular in the series of panel paintings at Amberley Castle in West Sussex: the collection of images was created in the 1520s by Lambert Barnard for the manor of the Bishop of Chichester Robert Sherborne. The heroines in the unstructured compilation are presented ready for battle in full armour and fully armed. The tituli installed beneath the images and inspired by both the ballade The Nine Ladies Worthy (late 15th or early 16th century) and the Chevalier errant recount their deeds.49Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 122; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 186.

The three Jewish women that John Ferne mentions in his armorial Blazon of Gentrie (1586) in praise of Queen Elizabeth are Deborah, Judith and Jael. Similarly, Thomas Heywood listed Esther, Deborah and Judith in his work of prose Gynaikeion, or, Nine Books of Various History Concerning Women (1624), written in homage to the recently deceased (1619) Anne of Denmark, the wife of King James I of England, and in his later work The Exemplary Lives and memorable Acts of Nine of the Most Worthy Women of the World: Three Jews. Three Gentiles. Three Christians (London, 1640), dedicated to Queen Henrietta Maria of France.50Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 128; Waith: “Heywood’s Women Worthies”, 1975, 225; Wright: “The Elizabethan Female Worthies”, 1946, 628. Schroeder mentions that the same biblical women appear in Sylvanus Morgan’s armorial The Sphere of the Gentry (1661). See Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 175, 177. These Jewish women embodied the courageous devotion of one’s own life for one’s people by which they brought about seminal political change. In panegyric texts, queens such as Elizabeth and Christina of Sweden were compared with the biblical heroines, who became virtue allegories of female rulership and, together with the other figures of the Worthies, were used for rule dramatisation, like in the festive procession for Elizabeth in Norwich in 1579.51Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 128; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 175. Regarding Christina of Sweden and her comparison with biblical heroines, see Saarinen, Risto: “Heroic Virtue (Protestantism)”. In: Compendium heroicum, ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher, Anna Schreurs-Morét, and Ralf von den Hoff, published by Sonderforschungsbereich 948, University of Freiburg, Freiburg 2023-12-07. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/htpe1.0.20231207; ⟶Heroic Virtue (Protestantism).

As Christian heroines representing the Christian age including the present, various female English rulers were included and their particular martial achievements were emphasised: besides Margaret of Anjou and Elizabeth, Heywood (1640) lists an English queen from the 9th century named Elphleda (Æthelflæd, the wife of King Æthelred).52Waith: “Heywood’s Women Worthies”, 1975, 229; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 229; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 177; Wright: “The Elizabethan Female Worthies”, 1946, 628, 641-643. In Blazon of Gentrie, Ferne names Matilda, the uncrowned ‘Lady of England’, who later became empress of the Holy Roman Empire, as well as Isabella of Aragon and Joanna II of Naples.53Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 128. The specific occasion for structuring the English canon is unknown, but it is unmistakable that by clearing away the ahistoricality of the Nine Ladies Worthy, a woman’s claim to rule relating to the present was formulated in opposition to the application of the Salic Law and national aspects were emphasised through the inclusion of female English rulers. The reference to the Worthies comes up in particular in the rule dramatisation of the queens Mary Stuart, Mary Tudor and Elizabeth.54Wright: “The Elizabethan Female Worthies”, 1946, 628. For more on the early modern debate surrounding feminine rule, see Opitz, Claudia: “Weibliche Herrschaft und Geschlechterkonflikte in der Politik des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts”. In: Garber, Klaus et al. (Eds.): Erfahrung und Deutung von Krieg und Frieden. Religion – Geschlechter – Natur und Kultur. Munich 2001: Wilhelm Fink, 507-520.

4. The Neun Gute Frauen – a system of humanist virtue heroism

Appearing somewhat earlier than in England, the nine heroines in Germany comprised three pagans, three Jews and three Christians, clearly breaking with the French tradition of the neuf preuses. Considered an influential visual document, three woodcuts made in 1519 by the Augsburg painter and illustrator Hans Burgkmair (1473–1530) divide the newly selected female figures into three triads assigned religious affiliations (figs. 6–8) in the style of the woodcuts of the nine heroes that were appearing at the same time.55It is unclear to date whether Burgkmair was the originator of the new canon. Baumgärtel describes him as one of the first to structure the female canon according to religious affiliation. See Baumgärtel, Bettina / Neysters, Silvia (Eds.): Die Galerie der Starken Frauen. Die Heldin in der französischen und italienischen Kunst des 17. Jahrhunderts (exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf, 10 September–12 November 1995; Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, 14 December–26 February 1996). Munich 1995: Klinkhardt & Biermann et al., 160, No. 47 (B. Baumgärtel). Since a copy of the woodcut with the three pagans shows the year 1516, it is assumed that the group had already been assembled at that point in time. The remaining folios that have survived are dated with 1519 without exception. See Russell, Helen Diane (Ed.): Eva/Ave. Woman in Renaissance and Baroque Prints (exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington). National Gallery of Art, Washington/New York 1990: The Feminist Press at The City University of New York, 36; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 174, 200. Like in the English canon, Judith, Esther and, in lieu of Deborah, Jael were the Jewish women selected to be included. All other figures of the German canon are new additions. The three pagans come solely from Roman antiquity (Lucretia, Veturia and Virginia). For the three Christian spots, it was not rulers from the recent past who were chosen, but three saints: Elizabeth of Hungary (1207–1231), Bridget of Sweden (1303–1373) and Empress Helena, mother of Constantine I (ca. 255–ca. 334).

Burgkmair’s concrete source of inspiration and the exact occasion for the canon’s new composition are unknown, but there is reason to believe that there was a humanist influence that aimed to visually improve the image held of women against the backdrop of the classical education canon.56Baumgärtel / Neysters: Galerie der Starken Frauen, 1995, 161, No. 47; Hans Burgkmair 1473–1973. Das graphische Werk (exhibition at the Graphische Sammlung Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 10 August–14 October 1973). Ed. by Isolde Lübbeke. Stuttgart 1973: Graphische Sammlung, Staatsgalerie, Nos. 106-111; Burgkmair und die graphische Kunst der deutschen Renaissance (exhibition at Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig, 30 September–25 November 1973), No. 20; Hans Burgkmair 1473–1531. Holzschnitte, Zeichnungen, Holzstöcke (exhibition at Altes Museum Berlin 1974, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett und Sammlung der Zeichnungen). Berlin 1974, Nos. 36.1-6. The interest in ancient and Old Testament hero figures, which was increasing in general during the period of early humanism, can be seen as an essential stimulus for Burgkmair’s espousal of the nine heroines. In choosing the Jewish women that he did, Burgkmair followed in the tradition shaped by Christine de Pizan and Antoine Astesan that, in honour of Joan of Arc, listed the biblical heroines (Esther, Judith and Deborah) who were classed together with the neuf preuses (Penthesilea most of all).57See note 46. Judith and Jael in particular, through their violent heroic deeds, represent the most distinct link between the Augsburg group and the older canon of the neuf preuses. Even though the biblical heroines, in contrast to the preuses, were not professional warriors, instead achieving their hero status through one single bloody deed to rescue their people, they make their potential combat readiness visible by carrying either a weapon or the head of Holofernes as an attribute. Judith most of all was associated with the preuse Tomyris, who hewed off the head of her enemy Cyrus and, in an act of revenge, placed it in a blood-filled bag. Like Judith and Jael, Tomyris was seen in mediaeval devotional literature, such as Speculum Humanae Salvationis, as a ⟶prefigurant of the Virgin Mary, who prevails over the devil and various vices.58Brown, Peter Scott: The Riddle of Jael. The History of a Poxied Heroine in Medieval and Renaissance Art and Culture. Leiden / Boston 2018: Brill, 35; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 218, 228; Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 68-69; Warner: Monuments & Maidens, 1985, 164. On an allegorical level, Judith and Jael are associated with the virtue of Fortitudo.

Giovanni Boccaccio’s De claris mulieribus, having been widely disseminated in Germany thanks to its 1473 translation (and a further 1479 translation in Augsburg) by Heinrich Steinhöwel, has been discussed as another tradition on which the Burgkmair series might be based. Since Boccaccio’s work includes almost exclusively individuals from mythology and classical history, it is a possible template for the three pagans, Lucretia, Veturia and Virginia.59 Wörner makes the case that Boccaccio was the source of inspiration for the Neun Gute Frauen. See Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 214; Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 29; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXIV; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 180. There have been debates whether Maximilian I influenced Burgkmair’s selection of the three saints as the Christian heroines because of the Habsburg coats of arms placed in the foreground. Maximilian I might have commissioned Burgkmair to portray these saints, who were not only quite popular particularly in Germany, but also significant for the self-image that the Habsburgs presented to society.60Helena, as Constantine’s mother, draws attention to the analogy between the empire of Constantine and the Holy Roman Empire under Maximilian. In particular, the Habsburg double-headed eagle in Helena’s coat of arms is meant to point to this association. Bridget, on the other hand, was very popular in Germany after the publication of her revelations in 1492. At the same time, her pilgrimage to the Holy Land might have corresponded with Maximilian’s interest in the Crusades. For more on this, see Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 37. Regarding Maximilian’s genealogy, which he traced back to the three Christians of the male canon and Elizabeth of Hungary, see Williams, Gerhild S.: “The Arthurian Model in Emperor Maximilian’s Autobiographic Writings Weisskunig and Theuerdank”. In: Sixteenth Century Journal 11.4 (1980), 3-22, 4. By contrast, the coats of arms of the pagan and Jewish women are largely not meant to be identifiable, which underscores the ahistorical character of the figures. See Baumgärtel / Neysters: Galerie der Starken Frauen, 1995, 160-161, No. 47; Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 36, No. 1. The fact that Elizabeth, Helena and Bridget were married or widowed aristocrats might indicate a corresponding group of addressees. In view of a booklet published in 1518 likewise in Augsburg (by publisher Hanns von Erffort) on the nine best and nine most infamous women and men (36 figures in total) that includes all the heroines from Burgkmair’s compendium, the question must remain unanswered as to whether or not the German canon was popular already before Burgkmair in less elitist forms of distribution.61The booklet, compiled by an anonymous author and illustrated throughout with woodcuts, bears the title “Hieriñ auff das kürtzest ist an gezaigt der dreien glauben dz ist der Haidñ Judñ uñ Cristen die frümbstẽ uñ pösten Mannen und frawen der höchsten geschlächt” (“Herein is examined in the briefest of terms the three faiths, namely pagans, Jews and Christians, the most pious and worst men and women of the greatest lineage”). One copy can be found in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum (Inv. 8L 1954p), and another with coloured woodcuts in the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. See Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 183. In the time thereafter, the Neun Gute Frauen appear primarily in works of art from Southern Germany, such as the collection of painted glasses (ca. 1535/40) stored at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, with precise copies of the Christian heroes and heroines according to Burgkmair, or in a series of copper engravings by Virgil Solis (1515–1562) that shows the figures in detailed drawings bordered by scrollwork.62Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Inv. Mm. 254/55. See Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 186; Augsburger Renaissance (exhibition at the Schaezler-Haus Augsburg, May–October 1955). Augsburg 1955: Die Brigg, Nos. 610-611. For more on the copper engravings by Virgil Solis, see Baumgärtel / Neysters: Galerie der Starken Frauen, 1995, 161, No. 47; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 200; Augsburger Renaissance, 1955, Nos. 106-111; Bartsch, Adam von: Le peintre graveur. Vol. IX. Vienna 1808: Degen, 253-254. Schroeder demonstrates how the German canon is reflected in the sculptural programme of the Lüneburg Town Hall. Based on the surviving fragments, he was able to identify Jael, Elizabeth and Bridget. Burgkmair’s selection of heroines also appear together with the heroes in the carvings of the south and west façades of Maison Kammerzell in Strasbourg. See Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 191, 193. An engraving series of the Neun Gute Frauen by Philips Galle according to Maerten de Vos proves the persistency of the subject into the 16th century.63 Munich, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Inv. 102 242.

Compared to the neuf preuses, Burgkmair’s heroines exhibit not just a new conceptualisation of the personal composition, but also a transformed appearance. Weapons and armour have been replaced by voluminous, pleated garments and attributes that closely associate the figures with the portrayals of virtue allegories or saints. The martial qualities of the French and English canon were unseated by moral and theological virtues.64Baumgärtel / Neysters: Galerie der Starken Frauen, 1995, 160-161, No. 47; Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 30, 37; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXI; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 174, 177, 200; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 227, 230. The three Christians were associated with the three Christian virtues of Spes, Fides and Caritas. It bears noting here that the association of Spes with the attribute of the anchor is not straightforward. The attributes being carried point to recounted heroic deeds and achievements or symbolise a specific way of living that is based on a virtue ideal. While Veturia’s jewellery and Verginia’s model of a temple are reminders of the expansions of women’s rights in ancient Rome that they forced through – the rights to wear jewellery in public and to enter a temple of Pudicitia as a plebeian woman65Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 30. Russell interprets Veturia’s conspicuously opulent jewellery as a symbol of her regal magnificence. However, the jewellery is a clear allusion to the social recognition of women described by Boccaccio that she achieved. In addition to introducing women’s right of succession, the new status also entailed the wearing of jewellery in public. See Steinhöwel: Von den erlauchten Frauen, 2014, 351. Burgkmair’s Virginia has to date likewise been incorrectly taken to be the daughter of Virginius. See Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 32, 36; Baumgärtel / Neysters: Galerie der Starken Frauen, 1995, 161, No. 47; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 229. However, Burgkmair is depicting the Roman woman that Boccaccio called Verginia, the wife of Lucius. To date, the temple model has been seen as being that of the Temple of Vesta. This interpretation must be corrected: it is the Temple of Pudicitia erected by Verginia. Philips Galle’s portrayal of Virginia also supports this understanding: in the background, the two temples for the aristocratic and plebeian women can be seen. The interpretation to date of the three pagans as the three feminine ages of life – virgin, wife and widow – is likewise untenable with this identification. Instead, it is striking that Burgkmair’s compilation completely lacks any figure that represents the status of virgin or, as it were, the unwedded woman. – Lucretia’s, Judith’s and Jael’s weapons represent their murderous deeds, which they did not commit out of any heroic fighting spirit, but as deeds of faith or indictments of moral injustice.66Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 177. In particular Judith, notwithstanding the topos of the nine heroines, evolved into the symbol of the tyrant’s overthrow and acted – like David – as an allegory of justice. See Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 32; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 228. Starting in the 16th century, Jael also became a popular theme in imagery to allude to moral and political crises. See Brown: The Riddle of Jael, 2018, 19. In this way, the heroines substantively deviate in distinct fashion from the concept of heroism of the neuf preux, although in terms of form the female canon did approximate the male canon by the way it was internally structured: in lieu of embodying chivalric ideal and warriorhood, their heroic deeds were now embedded in moral and theological discourses.

The radical exclusion of the martial heroine in the German canon has pithily been described as the transformation of the heroic ideal to the Christian ideal and a “product of the bourgeois age”.67Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 10, 128-129 (In the original: “Produkt des bürgerlichen Zeitalters”). Regarding the pre-eminent stylisation of female heroic figures into virtuous and suffering heroines (“Tugend- und Leidensheldinnen”), see Kroll, Renate: “Heroinismus/heroinism/Amazonomanie”. In: Kroll, Renate (Ed.): Metzler Lexikon Gender Studies. Geschlechterforschung. Ansätze – Personen – Grundbegriffe. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2002, 174-175. As the Augsburg booklet published by Hanns von Erffort in 1518 demonstrates, the preuses even evolved into anti-heroines: Queen Semiramis is listed there among the villainesses, having caused her son’s death due to her incestuous desires. In humanism, the mediaeval heroic biography, as a list of heroic deeds in court literature, was replaced by the moral discourse in which the heroines served as exempla in examining their actions in extraordinary situations.

At the visual level, the discursive character of heroism in Burgkmair’s woodcuts is expressed by the animated, communicative postures of the three pagan and three Jewish women. In each of those two groups, Burgkmair depicts the peacemaker, Veturia and Esther respectively, as the figure that is speaking. Because they performed their heroic deeds verbally in preventing belligerent actions against their peoples through courageous speeches, Burgkmair portrayed them as orators who with gestures and in magnificent clothing talk at their obviously younger companions associated with bloody deeds. The motif of the conversation in conjunction with corresponding oratory gestures links the figures to the mediaeval portrayals of virtue, such as those of Psychomachia, and at the same time points to the common practice in the early modern period of forming analogies between ancient and Old Testament themes that are juxtaposed in picture cycles or iconographic programmes and typologically interpreted.68For more on Esther, see Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 33, 37; Haug, Ingrid / Wilckens, Leonie von: “Esther”. In: Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte. Vol. VI (1968), cols. 48-88. Online at: http://www.rdklabor.de/w/?oldid=89027 (version dated 05.02.2015, last accessed 10.12.2019). Haug and Wilckens believe that the juxtaposition of Esther before Ahasuerus and Veturia before Coriolanus in the pictorial programme of the Imperial Hall at the Munich Residence was inspired by Burgkmair’s compendium of the nine heroines. A historic description of the programme in which Lucretia and Susanna, as well as Judith and David, are juxtaposed survives in Pallavicino, Ranuccio: I trionfi del’architettura nella sontuosa residenza di Monaco. Munich 1667, 12, 14-15. It is also highly likely that there is a connection between the woodcut series and the history paintings that were made for Duke Wilhelm IV of Bavaria a short time later. Additionally, the groups of figures placed in scenes of conversation illustrate the religious affiliations as self-contained categories of moral-theological systems of norms, meaning for example that suicide occurred only among the pagans and the bloody deed instigated by God happened only among the Old Testament heroines.

Nevertheless, the pagan and Jewish women share a motif of conflict with a specific male opponent whose sinister actions they put an end to through tyrannicide, the verbal power of persuasion or their own death. Their heroic deeds led to far-reaching political or societal changes, like the beginning of the Roman Republic after Lucretia’s death for example. Unlike the group of nine heroes, whose figures are associated with expansive conquests or the establishment of a certain rule and thus with the stabilisation of a political status quo, the heroines proved to be figures of political destabilisation whose individual deeds triggered upheavals and who thereby gained collective significance for the fate of their respective peoples.69On the subject of the upheavals instigated by the heroines, see Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 30, 36.

By contrast, the three Christian women, who embody the Christian age and thus Burgkmair’s present, are the only historically tangible, non-mythical figures, whose biographical data are chronicled in the Christian age and who conclude with Bridget of Sweden as the historically most recent heroine. To ensure recognisability, an especially correct rendering of the portrayals of the saints being newly integrated into the canon was obviously important to Burgkmair: in Helena’s profile, he made use of her Constantinian coin portrait, and he showed Bridget – consistent with her numerous well-known portrayals – in the white veil of her habit.70Helena’s coin portrait was available in Konrad Peutinger’s coin collection, to which Burgkmair might have had access. Halm, Peter: “Hans Burgkmair als Zeichner, Teil I”. In: Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst 13 (1962), 75-162, 89 ff. For more on the tradition of portraying Bridget in a monastic habit, see Nordenfalk, Carl: “Saint Bridget of Sweden As Represented in Illuminated Manuscripts”. In: Meiss, Millard (Ed.): Essays in Honor of Erwin Panofsky. Vol. 1. New York 1961: University Press, 371-393, 385, 390. Free from the substantive aspects of the biblical and classical heroines, no obvious typological equivalents are evident. This distinction is underlined by the programmatic silence and the statue-like, introspective postures of the three figures adorned with aureoles, who stand out in view of the expressive communicative postures of the Jewish and pagan women.71The interpretation to date of the introspective demeanour being the virtue of taciturnity, the central virtue of the Christian woman, contradicts the saints’ biographies. Bridget’s work as a political counsellor in the Swedish royal family and her active criticism of the French papal court, as well as Elizabeth’s highly provocative rejection of the aristocratic life were hardly perceived as ‘taciturn’ conformism by contemporaries. See the interpretation of the Christian women to date in Baumgärtel / Neysters: Galerie der Starken Frauen, 1995, 161, No. 47; Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 37. On Bridget’s openly voiced criticism, see Nordenfalk: “Saint Bridget of Sweden”, 1961, particularly 388. The formal and substantive disconnection of the Christian women possibly alludes to the Christian pretensions to surpass the classical heroes with their saints and to reveal the true meaning of the mysteries of the Old Testament in the gospels. As figures of the now prevailing Christian era, the three saints consequently are lacking any reference to political subversion or destabilisation. Instead, the Christian heroines are distinguishing themselves through pioneering achievements in areas that were future-oriented for Christianity. While Helena laid the foundations of pilgrimaging through her discovery of the cross and biblical sites in the Holy Land, Elizabeth of Hungary was involved in caring for the poor and infirm; Bridget achieved prominence for her service to the Roman papacy, the cloisters she established and recording her mystic revelations.72On Helena as the initiator of pilgrimaging, see Fortner, Sandra Ann / Rottloff, Andrea: Auf den Spuren der Kaiserin Helena. Römische Aristokratinnen pilgern ins Heilige Land. Erfurt 2000: Sutton. Besides her legendary finding of the cross, the location of which was revealed to her in a vision (Fortner / Rottloff: Auf den Spuren, 2000, 88-93), she was famous for founding churches. The most well-known source on Elizabeth of Hungary in Burgkmair’s time was her description in the Legenda aurea. The biographies of the three saints bespeak exceptional initiative and personal vigour that, together with the orientation towards Christian ideals, garnered them the greatest significance among the figures of the nine heroines as paragons of practical morality for their female contemporaries.73For more on this, see Russell, Helen Diane: Eva/Ave, 1990, 37. Hence, in summary, Burgkmair’s heroines managed to bridge the gap between myth and the historically valid era, which still seemed impossible with the preuses. Additionally, the grouping now had the same mandate as the men from both a world and salvation history standpoint through its internal structure in religious affiliation. Unlike the male group, however, the selection of women was able to develop new models of feminine heroism adapted to current influences over the course of its eventful history. Those models were emancipated from the purely martial appearance of the earlier preux and preuses.

5. The state of current scholarship and perspectives

The neuf preuses began to be mentioned in art historical studies as the interest in the nine heroes awoke in the mid-19th century. However, in the first hundred years of scholarship, only the male canon was systematically studied, having been considered more significant because of its earlier genesis and more expansive tradition. Generally, the collection of female figures was mentioned only marginally, and only in individual cases was it recognised as a distinct object of study, like in the reconstruction of the Salle des Preuses in Coucy by Viollet-le-Duc or in Guiffrey’s study on late mediaeval tapestries.74For more on Viollet-le-Duc’s reconstruction of the Salle, see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 9, 61; Guiffrey, Jules: “Note sur une tapisserie représentant Godefroy de Bouillon et sur les représentations des preux et des preuses au XVe siècles”. In: Mémoires de la Société des antiquaires de France X (1879), 97-110. This work unfortunately could not be obtained for me by the University Library Freiburg. The subsequent publications until the middle of the 20th century largely ignore their historical relevance: while Barbier de Montault underwhelmingly attempts to present some of the Coucy preuses as male figures, Huizinga (1924) and Wyss (1957) classify the preuses as a consequence complementing the male canon and meeting the late mediaeval need for symmetry that attracted attention at most because of its peculiar makeup.75On Barbier de Montault, see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 9, 63; Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1987 (1924), 74; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 74-75. The variability and, to an extent, lesser renown of the figures, the quantitatively inferior tradition, the lack of a pictorial programme in which the neuf preuses are portrayed autonomously, i.e. not together with the neuf preux, and the historical aspirations limited by the omission of an internal structure are repeatedly identified in scholarly literature, even until recently, as arguments for considering the neuf preuses as a so-called ‘secondary formation’, i.e. a manifestation subordinate to the primarily formed neuf preux and designed analogously to them.76Wörner still interprets the variability of the figures as a shortcoming and an incompleteness of the canon formation (“Unabgeschlossenheit der Kanonbildung”). According to her, Burgkmair’s German female canon represents the tertiary formation of the male canon. See Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 214, 226. Even though Schroeder devotes some space in his study of the neuf preux (1971) to examining the female figures and summarises the known material about them, he also follows a clear hierarchy of the two canons in using the aforementioned arguments.77 Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, particularly 168, 202. See the research report in Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 9-10; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, XV. The understanding of the characteristics of the male canon as the benchmark for the female canon and the resulting interpretation of deviations as deficits led to a dismissiveness that remained constant over a long period of time and a neglect of the neuf preuses as an object of study. The first extensive art historical monograph on the late mediaeval heroines, which is still considered a standard work today, was written by Sedlacek (1997). Besides the composition and classification of the pictorial tradition according to art history scholarship, she addresses the question of the literary source of the female canon, a central point of inquiry in scholarship on the neuf preux as well. While she does devote some attention to the English canon, which is associated with the French canon of the neuf preuses, Sedlacek’s study unequivocally ignores an examination of the Neun beste Frauen originating in Southern Germany.

While the English Nine Ladies Worthy have been discussed in connection with their importance for the praise of female rulers by Wright (1946) and Waith (1975), there still is no extensive study on the German canon. Hans Burgkmair’s woodcuts are described in catalogue entries in publications accompanying various exhibitions; however, there lacks any further contextualisation with collections of images of heroic and exemplary women in early modern printed imagery and in pictorial programmes from Southern Germany. Moreover, early humanist text-based discourses have yet to be taken into account. For future research, besides a more precise exploration of the German tradition, the expansion to further geographical areas, such as the Scandinavian countries for example, would be a worthwhile perspective. The most promising approach, however, appears to be a revision and expansion of the findings made thus far using methodological approaches that take into account the current state of gender studies. The no longer tenable understanding of the versatility of the female canon as an argument for a hierarchisation of the historical significance of the two canons should be replaced by dynamic perspectives orientated towards the concept of histoire croisée in order to unlock the view of the diversity of observable heroization phenomena. From a multiple-perspectives point of view, the transformation of the female canon can be understood as a remarkable feat of assimilation in view of geographical, social and cultural situations that reciprocally influenced one another. That ensured actualisations of the figures that were relevant to the present, and thereby prevented any anachronistic effect that can be a symptom of a lesser social relevance. The approach of using the ambiguity of heroines in order to appreciate with particular acuity nationally, morally and religiously defined discourses associated with them is already being used in recent scholarship on early modern heroines, such as in Brown’s monograph study on the biblical heroine Jael (2018), in which a nuanced spectrum of meaning of the figure over its reception history is developed.

6. References

- 1Huizinga, Johan: Herbst des Mittelalters. Studien über Lebens- und Geistesformen des 14. und 15. Jahrhunderts in Frankreich und in den Niederlanden. Stuttgart 1987: Kröner [First edition Munich 1924], 74; Wyss, Robert L.: “Die neun Helden. Eine ikonographische Studie”. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 17 (1957), 73-106, 74-75; Sedlacek, Ingrid: Die Neuf Preuses. Heldinnen des Spätmittelalters. Marburg 1997: Jonas, 10-11.

- 2The figures listed here correspond to the selection in the chivalric romance Le chevalier errant, which was influential for the formation of the canon. Other textual and visual sources may have different individual figures. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 11; Mamerot, Sébastien / Salamon, Anne (Eds.): Le traictié des neuf preues. Geneva 2016: Droz, LXVIII, LXXXIX.

- 3Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1987, 74; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 74-75; Schroeder, Horst: Der Topos der Nine Worthies in Literatur und bildender Kunst. Göttingen 1971: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 168, 172.

- 4Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 15, 99, 120-121; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, CXVIII; Wörner, Ulrike: Die Dame im Spiel. Spielkarten als Indikatoren des Wandels von Geschlechterbildern und Geschlechterverhältnissen an der Schwelle zur Frühen Neuzeit. Münster 2010: Waxmann, 220.

- 5Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 33-38; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXXIII. For more on the reception history of the Amazons, see Kroll, Renate: “Amazone”. In: Kroll, Renate (Ed.): Metzler Lexikon Gender Studies. Geschlechterforschung. Ansätze – Personen – Grundbegriffe. Stuttgart 2002: Metzler, 8; Kroll, Renate: “Die Amazone zwischen Wunsch- und Schreckbild. Amazonomanie in der frühen Neuzeit”. In: Garber, Klaus et al. (Eds.): Erfahrung und Deutung von Krieg und Frieden. Religion – Geschlechter – Natur und Kultur. Munich 2001: Wilhelm Fink, 521-537; Dlugaiczyk, Martina: “‘Pax Armata’: Amazonen als Sinnbilder für Tugend und Laster – Krieg und Frieden. Ein Blick in die Niederlande”. In: Garber, Klaus et al. (Eds.): Erfahrung und Deutung von Krieg und Frieden. Religion – Geschlechter – Natur und Kultur. Munich 2001: Wilhelm Fink, 539-567.

- 6Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 39.

- 7This view is also taken by Raynaud, Gaston: Oeuvres complètes de Eustache Deschamps XI. Paris 1903: Librairie de Firmin Didot et Cie, 225-227; Huizinga: Herbst des Mittelalters, 1987 (1924), 74; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 75.

- 8Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 47; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXI; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 169-171.

- 9Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 53.

- 10“Certes, a parler de prouesce, / Propose ma dame Leesce / Que les femelles sont plus preuses, / Plus vaillans et plus vertueuses / Que les masles ne furent oncques.” Quoted according to Hamel, A.-G. van: Les Lamentations de Matheolus et le Livre de Leësce de Jehan le Fèvre. Vol. 2. Paris 1905: Librairie Émile Bouillon, lines 3528-3532. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 54; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXX.

- 11A miniature placed before the text of an early illuminated copy (ca. 1400) that arguably shows Matheolus asking for forgiveness before a queen and her court has led some to speculate whether the patron was one of the French queens from that time period, namely Jeanne de Bourbon or Isabeau of Bavaria. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. fr. 24312, fol. 79. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 54-55.

- 12Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 55; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 171.

- 13Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 56, 78; Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 75.

- 14The castle, greatly damaged through war today, was built in the first half of the 13th century by Enguerrand III de Coucy, who traced his genealogy back to Hercules (Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 65). See Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 190.

- 15Today, the collection survives only in an engraving and a drawing by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (Les plus excellents bastiments de France) and a reconstruction drawing by Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc that is based on them. Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 58-61.

- 16The three-dimensional sculptures were placed in tower niches and formed a ring of female warrior protectors around the entire fortifications. The sculptures are roughly 2.50 meters tall, but are in very poor condition today. Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 81-82, 86-87, 89-90. As a counterpart, the Duke of Orléans decorated his castle Pierrefonds with larger-than-life figures of the preux, of which two survive in fragments today. See Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 190.

- 17Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 90.

- 18Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 91. Saying good or bad about women was a literary banality in both the Middle Ages and antiquity. Instead of developing a distinct and differentiated stance, mediaeval authors invariably identified themselves quite radically with either the one or the other stance. For more on this, see Meyer, Paul: “Plaidoyer en faveur des femmes”. In: Romania 6 (1877), 499-503, 499.

- 19Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 94-95, 98; Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 195-196.

- 20Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 196.

- 21Sedlacek considers Schroeder’s proposal of assuming Boccaccio as the source (Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 179; also Wörner: Die Dame im Spiel, 2010, 214) to be implausible. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 47; also Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXIII.

- 22See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 47, 51; Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXIV.

- 23Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 39, 96.

- 24Regarding France’s Trojan origin, see Hartwig: Einführung in die französische Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft, 130-131. Regarding the pro-Trojan stance in the French roman antique, see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 41, 43, 49. Like the French royal dynasty, the Burgundian dukes traced their origins back to Troy. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 109.

- 25For more on the Amazons in the Alexander Romance by Alexandre de Paris (after 1180) and in the Roman de Troie, see Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 40-42, 113.

- 26Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 43-44.

- 27Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 44, 66-70. See also Mamerot: Le traictié, 2016, LXXXII. Salamon associates the appearance of feminine chivalry with the crisis of masculinity that resulted from the failure of chivalry at the military level.

- 28Sedlacek believes that the appearance of the preuses during festive entrée parades is reflected in the drawings since they did not display any armour at the processions, but instead luxurious clothing and ornately painted coats of arms. See Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 72-73; see also Wyss: “Die neun Helden”, 1957, 82; Schroeder: Der Topos der Nine Worthies, 1971, 194. Schroeder cites a number of examples of conventional armorials in which the preuses are represented.

- 29Sedlacek: Die Neuf Preuses, 1997, 22, 30.