- Version 1.0

- published 15 August 2022

Table of content

- 1. Introduction

- 2. History and use of terms

- 3. Prefiguration as conceptualised by Hans Blumenberg

- 4. Heroic prefigurations

- 4.1. Prefigurant and prefigurate

- 4.2. Legitimisation and contingency reduction

- 4.3. Ambivalence and failure

- 4.4. Temporal structures of the heroic

- 5. Research perspectives

- 6. References

- 7. Selected literature

- 8. List of images

- Citation

1. Introduction

Heroic prefiguration is the process of establishing a reference between a source figure (prefigurant) and a target figure (prefigurate) for the purpose of conferring heroic status on the target figure or securing this status.1The article is based on the collective work of the Sonderforschungsbereich 948 on the topic of “prefiguration”. The text was edited by Georg Feitscher. The term goes back to Hans Blumenberg, who understood prefiguration as a mythical form of thought that serves as a “singular instrument of justification in weakly motivated actions”.2Blumenberg, Hans: Präfiguration. Arbeit am politischen Mythos. Berlin 2014: Suhrkamp, 14. Prefigurations are used as a rhetorical device to create acceptance for an action: Prefiguration lends “legitimacy to a decision that is extremely contingent and unexplainable.”3Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 10. With Blumenberg, we understand prefigurations as an instrument of legitimising rhetoric that is used in particular to secure ⟶heroizations and lend them plausibility. This is because referring to a model figure enables actors to justify their transgressive, controversial and possibly ⟶violent acts as heroic, and allows communities to build acceptance for their ⟶hero figures and anchor them in collective memory.

While Hans Blumenberg is interested in prefigurations as a means of heroic self-legitimisation, mythification and the staging of individual historical actors, the concept is equally instructive for the study of social heroization processes. In fact, prefigurative stagings are frequently resorted to in the collective attribution and constitution processes that produce heroes. For the attempt to assert and establish a new hero is more promising if reference can be made to an auspicious heroic role model, as whose successor and enhancement the heroic figure can be presented. Prefigurations thus are effective not only in situations where there is uncertainty about individual decisions, but also in situations where there is uncertainty about the collective evaluation of an event – for example, in those key moments in which it is still open as to whether a community demonises or heroizes the extraordinary and transgressive action of an actor. If a suitable heroic prefiguration can be found or constructed for the disputed figure, this can resolve the evaluative uncertainty in the direction of heroization.

Prefigurations are similar to another rhetorical legitimisation technique, imitatio heroica, which also establishes a relationship between a heroic source figure and a target figure.4Cf. von den Hoff, Ralf / Schreurs-Morét, Anna / Posselt-Kuhli, Christina / Hubert, Hans W. / Heinzer, Felix: „Imitatio heroica. On the Impact of a Cultural Phenomenon“. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 79-95. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/09. For the original publication in German see von den Hoff, Ralf / Schreurs-Morét, Anna / Posselt-Kuhli, Christina / Hubert, Hans W. / Heinzer, Felix: „Imitatio heroica – Zur Reichweite eines kulturellen Phänomens“. In: von den Hoff, Ralf / Heinzer, Felix / Hubert, Hans W. / Schreurs-Morét, Anna (Eds.): Imitatio heroica. Heldenangleichung im Bildnis. Würzburg 2015: Ergon, 9-33. However, while imitatio heroica is about conforming to a heroic model figure through imitation; heroic prefigurations go beyond the imitation of a given model. Here, the model does not exist as a fixed, largely unchangeable phenomenon, but is transformed or even created through the process of prefiguration. Blumenberg attaches great importance to this construction of the prefigurant, in which an initial figure is ‘made’ into a model, and it comes into effect in heroization processes in a special way. It is true that even in heroic prefigurations a reference is often made to well-known and established heroic figures in history. Nevertheless, in order to be able to function as a prefigurant, i.e. to be functionalisable as a role model with regard to the heroization of the target figure, a new meaning must be ascribed to the source figure that makes it relatable to contemporary needs. A central element of such prefigurative constructions is to make the prefigurate appear not as a mere imitation, but as a surpassing of the prefigurant or as the fulfilment of a promise inherent in the prefigurant. This relationship of surpassing between the source figure and the target figure goes back to the origins of prefigurative patterns of interpretation in Christian typology, in which a New Testament antítypos was interpreted as the fulfilment and intensification of an Old Testament týpos.

The strong affinity between heroization processes and prefigurative constellations indicates that heroic figures cannot be reduced to the role often ascribed to them as disruptive, tradition-breaking actors. Often, it is precisely the successful integration of heroes into historical references and traditions that lends legitimacy to a heroization and determines its success. Prefigurations achieve such integration; they create continuity and anchor heroes in the memory cultures of their communities. Prefigurations therefore offer an instructive model for the study of the ⟶temporal structures of the heroic.

2. History and use of terms

The concept of prefiguration goes back to Christian typology, in which a model from the past or from the Old Testament (designated as Greek týpos, Latin figura, later also praefiguratio) is placed in relation to a counter-image from the present or from the New Testament (Greek antítypos, Latin mostly veritas).5Augustinus, for example, refers to Mose as figura Christi (De civ. 10, 6; 18, 11), and to Noah’s Ark as praefiguratio ecclesiae (De civ. 15, 27). On the historical semantics of the figura concept cf. Auerbach, Erich: “Figura”. In: Auerbach, Erich: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur romanischen Philologie. 2nd, supplemented edition. Bern 1967 (first 1938): Francke, 55-92. In the typological scheme of interpretation, an antítypos is not interpreted as a mere repetition of a týpos, but as a heightening and fulfilment of the promising model set forth in the týpos.6Cf. Bohn, Volker: “Einleitung”. In: Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp, 7-21, 7-11.

Typology primarily served biblical exegesis, but was also used to establish connections between Christian and extra-biblical figures – for example, between Jesus Christ and ancient heroes such as Heracles.7Cf. Bohn: “Einleitung”, 1988, 7-8. The renewed expansion of typology in the 20th century into a secularised “way of thinking about history”8Ohly, Friedrich: “Typologie als Denkform der Geschichtsbetrachtung”. In: Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp, 22-63. without any foundation in salvation history was controversial.9The expansion of the concept of typology pursued by Auerbach and Ohly is opposed in particular by Schröder, Werner: “Zum Typologie-Begriff und Typologie-Verständnis in der mediävistischen Literaturwissenschaft”. In: Scholler, Harald (Ed.): The Epic in Medieval Society. Aesthetic and Moral Values. Tübingen 1977: Niemeyer, 64-85; cf. also Holländer, Hans: “‘… inwendig voller Figur’. Figurale und typologische Denkformen in der Malerei”. In: Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp, 166-205, 201. However, it opened up the concept – now primarily under the term “prefiguration” – for productive adoption in numerous humanities disciplines.

Thus, the concept of prefiguration has recently undergone many theoretical appropriations and modifications, for example with Northrop Frye and Hayden White (as a prefiguration-fulfillment model of historiographical narratives10Cf. Frye, Northrop: The Great Code. The Bible and Literature. New York 1982: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 80-81; White, Hayden: Metahistory. The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Baltimore/London 1973: Johns Hopkins University Press; White, Hayden: “Northrop Frye’s Place in Contemporary Cultural Studies”. In: White, Hayden: The Fiction of Narrative. Essays on History, Literature, and Theory 1957–2007. Edited and with an introduction by Robert Doran. Baltimore 2010: Johns Hopkins University Press, 263-272.), Paul Ricœur (préfiguration as a reference between fictional texts and extra-textual reality11Cf. Ricœur, Paul: Zeit und Erzählung. Vol. 1: Zeit und historische Erzählung. München 1988: Fink, 87-135.) or Carl Boggs (prefigurative politics12Boggs, Carl: “Marxism, Prefigurative Communism, and the Problem of Workers’ Control”. In: Radical America 11 (1977), 99-122, 100; Boggs, Carl: “Revolutionary Process, Political Strategy, and the Dilemma of Power”. In: Theory & Society 4.3 (1977), 359-393.). For the description of heroization processes, Hans Blumenberg’s essay Präfiguration. Arbeit am politischen Mythos (Prefiguration: Work on Political Myth) is informative.13Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014. See also Striet, Magnus / Dober, Benjamin: “Mythenverarbeitung. Oder: Zur Genealogie moderner Unübersichtlichkeit auf dem Feld des Heroischen”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 4.2 (2016), 17-22. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2016/02/02.

3. Prefiguration as conceptualised by Hans Blumenberg

In 1979, Hans Blumenberg explained in Work on Myth that he regards a historical person’s ‘self-reference’ to a figure who is considered a ‘hero’ to be an important element of the mythical ways of thinking that continued into modernity. As an example, he points out Goethe’s reference to Napoleon: “Goethe himself is always the point of reference – either openly or covertly – when he speaks of Napoleon”.14Blumenberg, Hans: Arbeit am Mythos. Frankfurt a. M. 1979: Suhrkamp, 504-566. Goethe also projects the ancient figure of Prometheus, which he also recreates as a poetic character, onto Napoleon. While Blumenberg did not pursue this phenomenon further in Work on Myth, he did consider Hitler and the National Socialists’ use of myths as political instruments later in his posthumously published Präfiguration. Arbeit am politischen Mythos (2014, originally conceived as part of Work on Myth, 1979).15Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, particularly 31-51.

By making the concept of prefiguration fruitful for describing the process of referring to heroic role models, Blumenberg also introduces a new terminology: He calls the heroic model figure a prefigurant (“Präfigurant”) and the after-image a prefigurate (“Präfigurat”). For Blumenberg, prefigurations can fulfil both contingency-reducing and legitimising functions because „the act of emulating a prefigurate is connected to the expected creation of an identical effect“.16Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 9. Blumenberg uses “Präfigurat” here instead of “Präfigurant”. This terminological inconsistency may be due to the fact that this is an estate manuscript not authorised by Blumenberg. However, it could also be an expression of the complex interrelationship between prefigurants and prefigurates outlined below. Prefigurations are effective especially in situations of decision-making uncertainty: Prefiguration lends “legitimacy to a decision that is extremely contingent and unexplainable” because “what has already been done once before does not require […] reconsideration”.17Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 9 and 10. The reference to a prefigurant therefore offers a “singular instrument of justification in weakly motivated actions”18Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 14. and positions people and actions “in the zone beyond doubt”19Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 15. and is used by actors for “self-legitimisation”20Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 16.. Once a prefigurative relation is established, it is difficult to dissolve, because it commits an action to being “impossible to abort” and gives “ultimate finality” to its results.21Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 17.

The process of prefiguration is characterised by several important features that are instructive with regard to the study of heroic phenomena. Primarily, Blumenberg understands the exemplary prefigurant not as a fixed and unchanging entity, but as the product of present processes of construction. Only in its alleged imitation is the prefigurant formed and attributed with meaning: the “model […] for the prefiguration is not born, but is made […]. What is repeated becomes […] a mythical agenda […] through repetition in the first place”.22Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 11.

Secondly, the prefigurant cannot be chosen arbitrarily, because “not every date, every event, every action can be elevated to a prefiguration through repetition […]”. Rather, the prefigurant needs to have “significance” and must be particularly “concise” and semantically condensed.23Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 14. According to Blumenberg, it is the conciseness and relevance of the prefigurant as a reference figure that distinguishes prefigurations from other forms of repetition. Due to its conciseness, however, the prefigurant is also “obliged to be repeated”24Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 11. because it is “difficult to leave the reference figure unused in situations of decision-making that are not supported by objective evidence, if only because the reference figure is potentially always available to others as well”.25Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 14.

4. Heroic prefigurations

4.1. Prefigurant and prefigurate

Following Blumenberg, we refer to an exemplary heroic source figure as a prefigurant, and to the target figure as a prefigurate.26In literary studies, “postfiguration” is also an established term for the target figure, while the initial figure is referred to as “prefiguration”. This terminology goes back to Albrecht Schöne’s interpretation of Andreas Gryphius’ Carolus Stuardus, cf. Schöne, Albrecht: “Figurale Gestaltung: Andreas Gryphius”. In: Schöne, Albrecht: Säkularisation als sprachbildende Kraft. Studien zur Dichtung deutscher Pfarrerssöhne. Göttingen 1958: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 29-75. Cf. also the criticism of Schöne’s concept of postfiguration, e.g. in Ohly: “Typologie als Denkform der Geschichtsbetrachtung”, 1988, 458; as well as Nagel, Barbara Natalie: Der Skandal des Literalen. Barocke Literalisierungen bei Gryphius, Kleist, Büchner. Munich 2012: Fink, 78-84. In fact, however, prefigurative relations between heroic figures are more complex than the simplistic proposition of source and target figure suggests.

First, depending on the context, a heroic figure can function as a prefigurant or a prefigurate – or be both at the same time. The status of prefigurant or prefigurate is not an intrinsic property of a figure, but an analytical category that describes how heroic figures are related to each other and are mutually functionalised in a specific historical constellation. It is not uncommon for a hero to be prefigured by an older figure and at the same time to form a prefiguring model for other heroes. George Washington, for example, was revered by his contemporaries as a heroic prefiguration of the Roman statesman and general Cincinnatus, because at the end of the War of Independence he freely gave up his powerful role as commander of the US army (see fig. 1). As a result, however, Washington himself quickly advanced to become a heroic prefigurant for his successors in the presidency.27Cf. Butter, Michael: Der “Washington-Code”. Zur Heroisierung amerikanischer Präsidenten 1775–1865. Göttingen 2016: Wallstein. Also, a series may be formed, in which a heroic figure is placed in relation to a sequence of prefigurants. For example, Italian fascists at the beginning of the 20th century “drew a line from Caesar to Napoleon to Mussolini […] who was then to surpass his predecessors as ‘emulo-superatore’”.28Beichle, Martin: “Der Sprung über den Rubikon. Zum Phänomen heroischer Präfigurationen am Beispiel zweier Stationen der Caesar-Rezeption.” In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 9.1 (2021), 5-14. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2021/01/01.

Secondly, the heroic prefigurant does not exist as a fixed and unchanging entity, but is only shaped in the process of prefiguration and given a meaning that makes it possible to assert the prefigurate as the fulfilment of the promise invested in the prefigurant. This means that not only the target figure but also the initial figure is transformed in the process of prefiguration. This reciprocal dynamic, in which both constituents of the relation are first created and related to each other, distinguishes prefigurative processes from unidirectional phenomena of reception, after-effect or imitation. Moreover, the concealment of contingency, which is achieved through the rhetorical technique of prefiguration, not only affects the heroized target figure, but also has an effect on the source figure: it, too, must be rhetorically freed from contingency and ambivalence in the course of prefigurative construction in order to be able to be utilised as a model for heroization that can no longer be questioned.

Thirdly, the meaning or ‘significance’ of a prefigurant is not given, but is bestowed upon it by those who use it to heroize someone else. This attribution of meaning, through which the prefigurant is constituted and asserted as a role model in the first place, is primarily aimed at the historical context of the community heroizing the prefigurate, and not the prefigurant itself. Blumenberg draws attention to the fact that in principle any figure can be elevated to a heroic role model as long as it can be functionalised with regard to the claimed prefigurate. Such ‘prefigurative potential’ is not only inherent in individual historical figures, but also in certain types of actions such as battles, incidences of self-sacrifice, voyages of discovery or, for example, river crossings. The reference to a significant role model can therefore encompass three aspects: The exemplary individual (e.g. Gaius Julius Caesar), the general type of action (e.g. river crossings), and the concrete event or action (the crossing of the Rubicon).29Cf. Beichle, Martin: “Der Sprung über den Rubikon”, 2021. It seems that it is precisely the combination of these levels that produces particularly significant and concise source figures, i.e. that a heroic figure linked in collective memory to a specific action can be used prefiguratively better than the figure or event alone.

Finally, the relationship between týpos and antítypos, which is already constitutive of biblical typology, becomes particularly relevant in the relationship between prefigurants and prefigurates: the heroic status of a figure can be further strengthened by portraying it as surpassing its prefigurant. A prefiguration can therefore be understood as a backdrop or ‘foil figure’ that contrastively or comparatively contours the heroic greatness of a figure.30On the concept of ‘foil figure’ cf. Beck, Hans: “Interne synkrisis bei Plutarch”. In: Hermes 130.4 (2002), 467-489, 468-469. The comparison of prefigurant and prefigurate can be implicitly evoked or shaped in an explicit narrative of surpassing.31An example of the explicit use of prefigurative ‘foil figures’ is the stylistic device of the ‘synkrisis’, i.e. the comparison of figures from different cultural circles, e.g. in Plutarch’s parallel biographies, in each of which a Greek and a Roman hero are compared; cf. Beck: “Interne synkrisis bei Plutarch”, 2002. In the extreme case, the prefiguration can even be based on a destructive intention, if an earlier hero is to fade completely in the radiance of the new hero. In this case, the heroization of the prefigurate goes hand in hand with the deheroization of the prefigurant.

4.2. Legitimisation and contingency reduction

In particular, the political-social functions of contingency reduction and legitimisation of action focused on by Blumenberg can be made fruitful for the analysis of heroization processes: Prefiguration is a rhetorical technique that generates security in times of crisis by appearing to provide ultimate justifications and by refusing to grant legitimacy to arguments and criticism. It also resembles heroization and other forms of social symbolisation, because the same is true for the heroic.32Cf. Langbein, Birte: “Die instrumentelle und die symbolische Dimension der Institutionen bei Arnold Gehlen”. In: Göhler, Gerhard (Ed.): Institution – Macht – Repräsentation. Wofür politische Institutionen stehen und wie sie wirken. Baden-Baden 1997: Nomos, 143-176, 158, 161-163; Soeffner, Hans-Georg: Auslegung des Alltags – Der Alltag der Auslegung. Zur wissenssoziologischen Konzeption einer sozialwissenschaftlichen Hermeneutik. Konstanz 2004: UVK, 163; as well as in the context of SFB 948: von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms: Transformations and Conjunctures from Antiquity to Modernity: Foundational Concepts of the Collaborative Research Centre SFB 948”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 9-16, 10. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/02; Asch, Roland G.: “Heros, Friedensstifter oder Märtyrer? Optionen und Grenzen heroischen Herrschertums in England, ca. 1603–1660”. In: Wrede, Martin (Ed.): Die Inszenierung der heroischen Monarchie. Frühneuzeitliches Königtum zwischen ritterlichem Erbe und militärischer Herausforderung. München 2014: Oldenbourg, 196-215, 200-202. Blumenberg’s concept of prefiguration directed at self-mythifications and self-legitimisations can therefore be transferred to the social processes of attribution and constitution that we call ‘heroization’. Prefigurations then unfold their effects in two different fields of contingency that are significant for the constitution of heroic figures: They lend the appearance of certainty and legitimacy to both the individual decisions of actors and the collective evaluations of transgressive actions by constructing heroic precedents.The contingency-reducing function is significant for the heroic because an actor’s transgressive, norm-breaking and/or violent action often has a polarising effect: It evokes uncertainty in a community as to how the act should be evaluated, whether it should be demonised or heroized .33Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “Transgressiveness”. In: Compendium heroicum, ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher, Anna Schreurs-Morét, and Ralf von den Hoff, published by Sonderforschungsbereich 948, University of Freiburg, Freiburg 2022-08-19. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/ge1.0.20220819. This tipping moment can be resolved in favour of heroization if a suitable heroic role model exists for the controversial figure. Historical examples show that prefigurative self-legitimisation is also used preemptively by actors announcing their own ‘heroic-transgressive’ action and legitimising it ex ante by referring to a prefigurant: “The commissive speech act highlights the exceptionality of the speaker as well as of those involved in the transgression”34Aurnhammer, Achim / Beichle, Martin: “Flussüberquerung”. In: Compendium heroicum. Das Online-Lexikon des Sonderforschungsbereich 948 “Helden – Heroisierungen – Heroismen” der Universität Freiburg, Freiburg 28.01.2021. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/fued1.0.20210128. – and thus anticipates the evaluation of the act by the community. However, the prefigurative overcoming of evaluation uncertainty is not only effective in the construction of heroic figures, but also in their antagonists, who can be interpreted as a typological heightening in malam partem (e.g. the Antichrist as the fulfilment of the Pharaoh or Goliath).35Ohly: “Typologie als Denkform der Geschichtsbetrachtung”, 1988, 35. In these cases, too, prefigurations guarantee certainty of evaluation, but they aim at the demonisation rather than the heroization of figures.

Blumenberg draws attention to the fact that the prefigurative legitimisation of contingent actions almost inevitably turns into normative absolutism36Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 23.: Once the prefiguration is established, “it may not be questioned again, but calls for total obedience in mythical self-commitment”. Moreover, “the commitments entered into must not be minimised”.37Striet / Dobler: “Mythenverarbeitung”, 2016, 20. The heroic prefiguration thus becomes an obligation both for the hero, whose deed must not fall behind the model and must surpass it if possible, and for his admirers, who affirm the prefigurative logic of heroization, and can thus create a heroic collective.

4.3. Ambivalence and failure

Contrary to their legitimising and contingency-reducing intention, the actual effects of prefigurative stagings are often ambivalent and unpredictable. For by referring back to a heroic role model, the exceptional and transgressive moment of an act is not only authenticated and strengthened, but sometimes also relativised – especially when the act is not perceived as a surpassing, but as a mere imitation of a role model. Heroic prefigurations fail when the target figure cannot be credibly claimed as the fulfilment of the promise inherent in the prefigurant, when the prefigurant proves to be unsuitable or when the entire reference seems too contrived. The prefiguration then misses its goal of legitimising the heroization of a figure and presenting it as having no alternative.

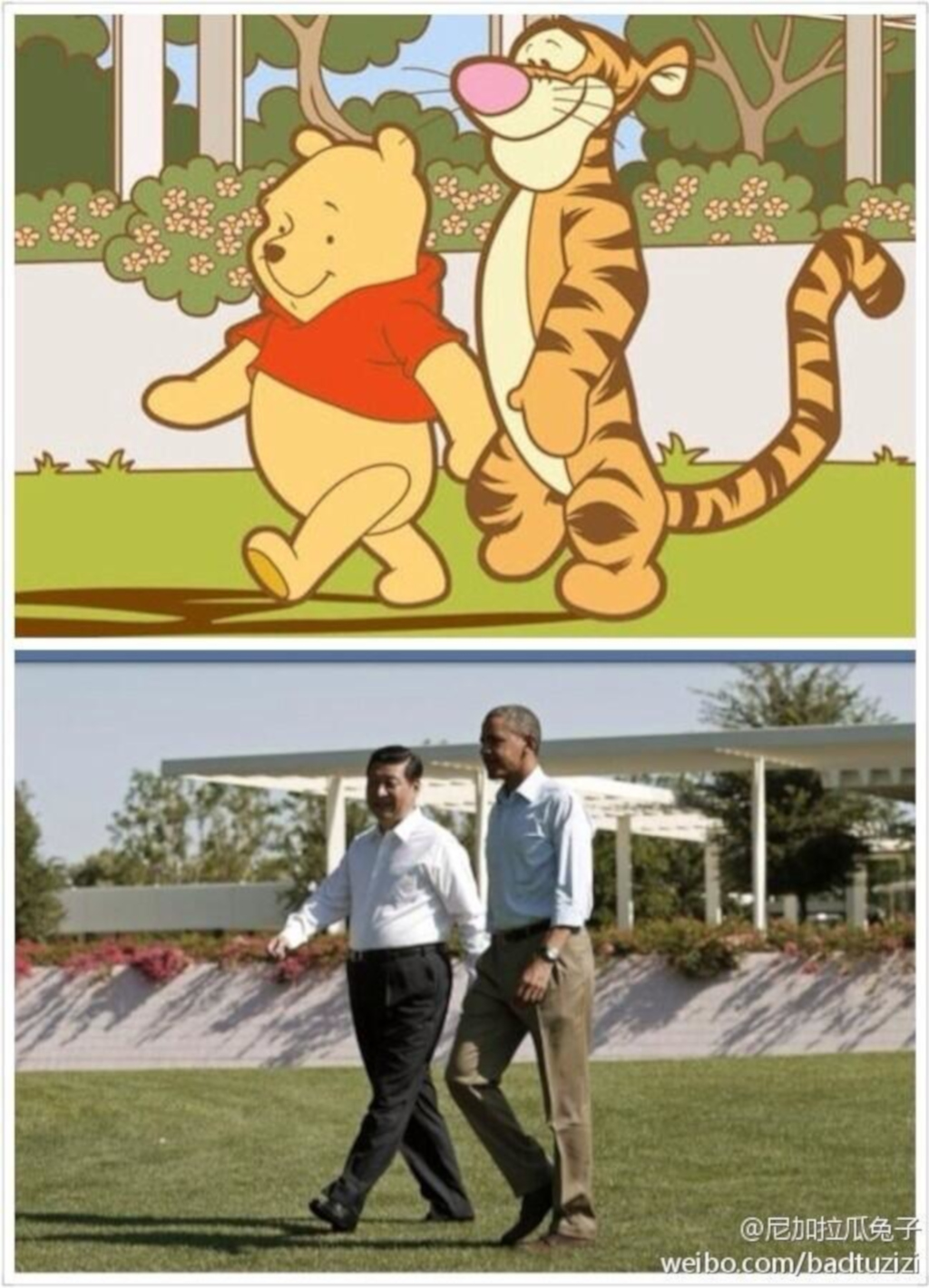

Moreover, prefigurative heroizations presuppose a prior knowledge on the part of the audience, on which their effectiveness depends. Only if the addressed audience understands the historical reference because they are familiar with the initial figure and the narratives associated with it can the prefiguration succeed. However, for those who are not part of the addressees, who are not invested in the mythical programme of a prefiguration or who do not have the necessary prior knowledge, the action can seem unintentionally comic. A comic effect also occurs when the audience perceives the reference between prefigurate and prefigurant as completely inappropriate or inadequate. Heroic prefigurations thus always carry the risk of creating the opposite effect and contributing to the ridicule of the target character. They therefore lend themselves to satirical use, in which deliberate comic references to unsuitable prefigurants are constructed in order to ridicule and deheroize the target figure. This principle underlies not least the memes that are widespread in social networks, which attempt to satirically undermine the typical heroizing representations of important people by creating visual analogies to deheroizing ‘prefigurants’. This is exemplified by a meme popular in Chinese networks in 2013, which used visual analogies to show the children’s book characters Winnie the Pooh and Tigger as role models for the presidents Xi Jinping and Barack Obama (see fig. 2).

4.4. Temporal structures of the heroic

With the concept of ‘prefiguration’, Blumenberg refers to the inherent power of an historical stock of meanings that is recalled in a given situation. Prefigurations explain the appellative character as well as the identification, mobilisation and imitation potential that emanates from pasts that can be retrieved in collective memory and postulated as significant. They are parts of repetition structures and assert the present as something that has allegedly existed before. This conception is connectable to the historiographical model of ⟶“sediments of time” proposed by Reinhard Koselleck, which understands historical times less as a diachronic sequence than as a phenomenon of multi-layeredness, polyvalent semantics and the simultaneity of levels of meaning that seem historically disparate. Common to both concepts is the perspective on historical practices as non-linear processes in which past and present meanings or figures interact with each other. For the description of the temporal structures of the heroic, both models complement each other in a productive way: While the “Sediments of Time” model aims at a more abstract level of analysis by looking at the superimposition and amalgamation of narrative patterns, conventions of representation, character types and characteristics of different epochs, the concept of prefiguration is particularly suitable for describing and analysing concrete individual characters in heroization processes. It is only in the combination of the two complementary terms that the temporal structures of the heroic can be grasped.

The strong affinity between heroization processes and prefigurative constellations indicates that heroic figures cannot be reduced to the role often ascribed to them as disruptive, tradition-breaking actors. Often, it is precisely the successful integration of heroes into historical references and traditions that lends legitimacy to a heroization and determines its success. Prefigurations achieve such integration. They create continuity and inscribe heroes in the collective memory. Heroic figures are thus characterised by an ambivalent simultaneity of continuity and discontinuity, of stabilisation and disruption. This ambivalence is only partially resolved by the prefiguration’s claim to surpass and replace a role model.

5. Research perspectives

If one understands prefiguration as a mechanism that constructs continuity, the question also arises as to the causes of the need to anchor heroic figures in historical references and continuities in the first place. Whether or not the affinity between heroizations and prefigurations is subject to cultural and historical differences also needs to be explored. For example, is legitimacy in modern societies generated more by references to the future than to the past? Does the symbolic conciseness, significance and binding nature of heroic prefigurants continue to have an effect today, or is prefigurative thinking losing importance overall?

There also seem to be relatively fixed repertoires of heroic prefigurants that can be repeatedly given new meaning and be used for prefigurations. An investigation informed by memory studies could shed light on how these repertoires are anchored and updated in the collective memory of a community. Linked to this is the question of their latencies and their normative effects: Under what circumstances can prefigurative repertoires be activated or their use even become obligatory? What interpretive knowledge of the respective publics do they presuppose?

6. References

- 1The article is based on the collective work of the Sonderforschungsbereich 948 on the topic of “prefiguration”. The text was edited by Georg Feitscher.

- 2Blumenberg, Hans: Präfiguration. Arbeit am politischen Mythos. Berlin 2014: Suhrkamp, 14.

- 3Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 10.

- 4Cf. von den Hoff, Ralf / Schreurs-Morét, Anna / Posselt-Kuhli, Christina / Hubert, Hans W. / Heinzer, Felix: „Imitatio heroica. On the Impact of a Cultural Phenomenon“. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 79-95. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/09. For the original publication in German see von den Hoff, Ralf / Schreurs-Morét, Anna / Posselt-Kuhli, Christina / Hubert, Hans W. / Heinzer, Felix: „Imitatio heroica – Zur Reichweite eines kulturellen Phänomens“. In: von den Hoff, Ralf / Heinzer, Felix / Hubert, Hans W. / Schreurs-Morét, Anna (Eds.): Imitatio heroica. Heldenangleichung im Bildnis. Würzburg 2015: Ergon, 9-33.

- 5Augustinus, for example, refers to Mose as figura Christi (De civ. 10, 6; 18, 11), and to Noah’s Ark as praefiguratio ecclesiae (De civ. 15, 27). On the historical semantics of the figura concept cf. Auerbach, Erich: “Figura”. In: Auerbach, Erich: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur romanischen Philologie. 2nd, supplemented edition. Bern 1967 (first 1938): Francke, 55-92.

- 6Cf. Bohn, Volker: “Einleitung”. In: Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp, 7-21, 7-11.

- 7Cf. Bohn: “Einleitung”, 1988, 7-8.

- 8Ohly, Friedrich: “Typologie als Denkform der Geschichtsbetrachtung”. In: Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp, 22-63.

- 9The expansion of the concept of typology pursued by Auerbach and Ohly is opposed in particular by Schröder, Werner: “Zum Typologie-Begriff und Typologie-Verständnis in der mediävistischen Literaturwissenschaft”. In: Scholler, Harald (Ed.): The Epic in Medieval Society. Aesthetic and Moral Values. Tübingen 1977: Niemeyer, 64-85; cf. also Holländer, Hans: “‘… inwendig voller Figur’. Figurale und typologische Denkformen in der Malerei”. In: Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp, 166-205, 201.

- 10Cf. Frye, Northrop: The Great Code. The Bible and Literature. New York 1982: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 80-81; White, Hayden: Metahistory. The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Baltimore/London 1973: Johns Hopkins University Press; White, Hayden: “Northrop Frye’s Place in Contemporary Cultural Studies”. In: White, Hayden: The Fiction of Narrative. Essays on History, Literature, and Theory 1957–2007. Edited and with an introduction by Robert Doran. Baltimore 2010: Johns Hopkins University Press, 263-272.

- 11Cf. Ricœur, Paul: Zeit und Erzählung. Vol. 1: Zeit und historische Erzählung. München 1988: Fink, 87-135.

- 12Boggs, Carl: “Marxism, Prefigurative Communism, and the Problem of Workers’ Control”. In: Radical America 11 (1977), 99-122, 100; Boggs, Carl: “Revolutionary Process, Political Strategy, and the Dilemma of Power”. In: Theory & Society 4.3 (1977), 359-393.

- 13Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014. See also Striet, Magnus / Dober, Benjamin: “Mythenverarbeitung. Oder: Zur Genealogie moderner Unübersichtlichkeit auf dem Feld des Heroischen”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 4.2 (2016), 17-22. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2016/02/02.

- 14Blumenberg, Hans: Arbeit am Mythos. Frankfurt a. M. 1979: Suhrkamp, 504-566.

- 15Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, particularly 31-51.

- 16Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 9. Blumenberg uses “Präfigurat” here instead of “Präfigurant”. This terminological inconsistency may be due to the fact that this is an estate manuscript not authorised by Blumenberg. However, it could also be an expression of the complex interrelationship between prefigurants and prefigurates outlined below.

- 17Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 9 and 10.

- 18Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 14.

- 19Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 15.

- 20Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 16.

- 21Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 17.

- 22Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 11.

- 23Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 14.

- 24Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 11.

- 25Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 14.

- 26In literary studies, “postfiguration” is also an established term for the target figure, while the initial figure is referred to as “prefiguration”. This terminology goes back to Albrecht Schöne’s interpretation of Andreas Gryphius’ Carolus Stuardus, cf. Schöne, Albrecht: “Figurale Gestaltung: Andreas Gryphius”. In: Schöne, Albrecht: Säkularisation als sprachbildende Kraft. Studien zur Dichtung deutscher Pfarrerssöhne. Göttingen 1958: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 29-75. Cf. also the criticism of Schöne’s concept of postfiguration, e.g. in Ohly: “Typologie als Denkform der Geschichtsbetrachtung”, 1988, 458; as well as Nagel, Barbara Natalie: Der Skandal des Literalen. Barocke Literalisierungen bei Gryphius, Kleist, Büchner. Munich 2012: Fink, 78-84.

- 27Cf. Butter, Michael: Der “Washington-Code”. Zur Heroisierung amerikanischer Präsidenten 1775–1865. Göttingen 2016: Wallstein.

- 28Beichle, Martin: “Der Sprung über den Rubikon. Zum Phänomen heroischer Präfigurationen am Beispiel zweier Stationen der Caesar-Rezeption.” In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 9.1 (2021), 5-14. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2021/01/01.

- 29Cf. Beichle, Martin: “Der Sprung über den Rubikon”, 2021.

- 30On the concept of ‘foil figure’ cf. Beck, Hans: “Interne synkrisis bei Plutarch”. In: Hermes 130.4 (2002), 467-489, 468-469.

- 31An example of the explicit use of prefigurative ‘foil figures’ is the stylistic device of the ‘synkrisis’, i.e. the comparison of figures from different cultural circles, e.g. in Plutarch’s parallel biographies, in each of which a Greek and a Roman hero are compared; cf. Beck: “Interne synkrisis bei Plutarch”, 2002.

- 32Cf. Langbein, Birte: “Die instrumentelle und die symbolische Dimension der Institutionen bei Arnold Gehlen”. In: Göhler, Gerhard (Ed.): Institution – Macht – Repräsentation. Wofür politische Institutionen stehen und wie sie wirken. Baden-Baden 1997: Nomos, 143-176, 158, 161-163; Soeffner, Hans-Georg: Auslegung des Alltags – Der Alltag der Auslegung. Zur wissenssoziologischen Konzeption einer sozialwissenschaftlichen Hermeneutik. Konstanz 2004: UVK, 163; as well as in the context of SFB 948: von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms: Transformations and Conjunctures from Antiquity to Modernity: Foundational Concepts of the Collaborative Research Centre SFB 948”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 9-16, 10. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/02; Asch, Roland G.: “Heros, Friedensstifter oder Märtyrer? Optionen und Grenzen heroischen Herrschertums in England, ca. 1603–1660”. In: Wrede, Martin (Ed.): Die Inszenierung der heroischen Monarchie. Frühneuzeitliches Königtum zwischen ritterlichem Erbe und militärischer Herausforderung. München 2014: Oldenbourg, 196-215, 200-202.

- 33Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “Transgressiveness”. In: Compendium heroicum, ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher, Anna Schreurs-Morét, and Ralf von den Hoff, published by Sonderforschungsbereich 948, University of Freiburg, Freiburg 2022-08-19. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/ge1.0.20220819.

- 34Aurnhammer, Achim / Beichle, Martin: “Flussüberquerung”. In: Compendium heroicum. Das Online-Lexikon des Sonderforschungsbereich 948 “Helden – Heroisierungen – Heroismen” der Universität Freiburg, Freiburg 28.01.2021. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/fued1.0.20210128.

- 35Ohly: “Typologie als Denkform der Geschichtsbetrachtung”, 1988, 35.

- 36Blumenberg: Präfiguration, 2014, 23.

- 37Striet / Dobler: “Mythenverarbeitung”, 2016, 20.

7. Selected literature

- Auerbach, Erich: “Figura”. In: Auerbach, Erich: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur romanischen Philologie. 2nd, supplemented edition. Bern 1967 (first 1938): Francke, 55-92.

- Beck, Hans: “Interne synkrisis bei Plutarch”. In: Hermes 130.4 (2002), 467-489.

- Beichle, Martin: “Der Sprung über den Rubikon. Zum Phänomen heroischer Präfigurationen am Beispiel zweier Stationen der Caesar-Rezeption.” In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 9.1 (2021), 5-14. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2021/01/01.

- Blumenberg, Hans: Work on Myth. Transl. by Robert M. Wallace. Cambridge, MA 1988: MIT Press. (German original: Blumenberg, Hans: Arbeit am Mythos. Frankfurt a. M. 1979: Suhrkamp.)

- Blumenberg, Hans: Präfiguration. Arbeit am politischen Mythos. Berlin 2014: Suhrkamp.

- Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp.

- Butter, Michael: Der “Washington-Code”. Zur Heroisierung amerikanischer Präsidenten 1775–1865. Göttingen 2016: Wallstein.

- Frye, Northrop: The Great Code. The Bible and Literature. New York 1982: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 80-81.

- Holländer, Hans: “‘… inwendig voller Figur’. Figurale und typologische Denkformen in der Malerei”. In: Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp, 166-205.

- Ohly, Friedrich: Typologie als Denkform der Geschichtsbetrachtung. In: Bohn, Volker (Ed.): Typologie. Internationale Beiträge zur Poetik. Frankfurt a. M. 1988: Suhrkamp, 22-63.

- Schöne, Albrecht: “Figurale Gestaltung: Andreas Gryphius”. In: Schöne, Albrecht: Säkularisation als sprachbildende Kraft. Studien zur Dichtung deutscher Pfarrerssöhne. Göttingen 1958: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 29-75.

- Schröder, Werner: “Zum Typologie-Begriff und Typologie-Verständnis in der mediävistischen Literaturwissenschaft”. In: Scholler, Harald (Ed.): The Epic in Medieval Society. Aesthetic and Moral Values. Tübingen 1977: Niemeyer, 64-85.

- Striet, Magnus / Dober, Benjamin: “Mythenverarbeitung. Oder: Zur Genealogie moderner Unübersichtlichkeit auf dem Feld des Heroischen”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 4.2 (2016), 17-22. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2016/02/02.

- von den Hoff, Ralf / Schreurs-Morét, Anna / Posselt-Kuhli, Christina / Hubert, Hans W. / Heinzer, Felix: „Imitatio heroica. On the Impact of a Cultural Phenomenon“. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 79-95. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/09. (For the original publication in German see von den Hoff, Ralf / Schreurs-Morét, Anna / Posselt-Kuhli, Christina / Hubert, Hans W. / Heinzer, Felix: „Imitatio heroica – Zur Reichweite eines kulturellen Phänomens“. In: von den Hoff, Ralf / Heinzer, Felix / Hubert, Hans W. / Schreurs-Morét, Anna (Eds.): Imitatio heroica. Heldenangleichung im Bildnis. Würzburg 2015: Ergon, 9-33.)

- White, Hayden: “Northrop Frye’s Place in Contemporary Cultural Studies”. In: White, Hayden: The Fiction of Narrative. Essays on History, Literature, and Theory 1957–2007. Edited and with an introduction by Robert Doran. Baltimore 2010: Johns Hopkins University Press, 263-272.

- White, Hayden: Metahistory. The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Baltimore/London 1973: Johns Hopkins University Press.

8. List of images

- 1“Washington, the Cincinnatus of America”, 1860/61, medal after a design by George Hampden Lovett.Licence: Public Domain

- 2Xi Jinping and Barack Obama ‘prefigured’ by Winnie the Pooh and Tigger, Satirical meme that was popular on Chinese short messaging service Weibo in 2013.Source: XQ / Twitter.comLicence: Quotation (German Act on Copyright and Related Rights, Section 51 / § 51 UrhG)