- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 7. November 2022

Inhalt

1. Introduction

Heroization processes1For reasons of terminological consistency with other SFB publications, we use the American English spelling of “heroization” and its derivatives (“to heroize”, “deheroization”, etc.). Cf. in particular von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms: Transformations and Conjunctures from Antiquity to Modernity: Foundational Concepts of the Collaborative Research Centre SFB 948”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 9-16. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/02. For the original publication in German see von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Helden – Heroisierungen – Heroismen. Transformationen und Konjunkturen von der Antike bis zur Moderne. Konzeptionelle Ausgangspunkte des Sonderforschungsbereichs 948”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 1.1 (2013), 7-14. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2013/01/03. are often closely linked to the specific form of communication that is propaganda. Hero figures become relevant in the context of propaganda in two ways. First, they can be the subject of the propaganda – for example as martyrs, martial heroes, war photographers, or labour heroes. As the subject of persuasive, (mass) media communication that also aims at long-term effective convincing, heroes2The term “heroes” refers to heroes of all genders. However, remarkably few women found and still find their way into the canon of heroes (not to mention non-binary or transgender persons). form engrossing communication patterns not just for the Western societies of the 20th century. Different media and different functions of propaganda construct and establish heroic figures, each with different connotations.

Second, persons perceived as ⟶heroes seem to be extremely persuasive communicators of the messages that propaganda conveys because of the exceptionality attributed to them and the special “appellative power”3von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms”, 2019, 12. that comes with that exceptionality. Propaganda heroes substantiate such messages and motivate the addressees to action. Heroes are therefore considered exceedingly suited to convey propagandistic content effectively to an audience.

2. Propaganda as a heroization strategy

To be a hero, an individual must be labelled as such, presented to an audience, and perceived by that audience as a hero.4For more, cf. von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Das Heroische in der neueren kulturhistorischen Forschung: Ein kritischer Bericht”. In: H-Soz-Kult, 28.07.2015. Online at: http://www.hsozkult.de/literaturereview/id/forschungsberichte-2216 (accessed 2022-10-26); and von den Hoff et al.: “Helden – Heroisierungen – Heroismen”, 2013. Propaganda is one of a number of (historically specific) communicative settings in which heroes are presented. Propaganda transforms a group – for example, a group of soldiers – into the social figure of the heroic soldier, or the individuals among them into exemplary heroes. Temporality plays a role in this respect in two ways: ⟶heroizations by means of propaganda can (firstly) draw upon older (visual) (re)presentations. The heroizing (re)presentation of Wehrmacht soldiers in illustrated magazines for instance referenced inter alia (visual) representations of soldiers of the First World War or of the Spanish Civil War.5For more, cf. Protte, Katja: “Das Erbe des Krieges. Fotografien aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg als Mittel nationalsozialistischer Propaganda im ‘Illustrierten Beobachter’ 1926–1939”. In: Fotogeschichte 16.60 (1996), 19-43. Secondly, propaganda does not aim just at producing short-term effects; hero figures are also used in the hope that the messages tied to them will achieve long-term impacts.6On the temporality aspect, cf. Gries, Rainer: “Zur Ästhetik und Architektur von Propagemen. Überlegungen zu einer Propagandageschichte als Kulturgeschichte”. In: Gries, Rainer / Schmale, Wolfgang (Eds.): Kultur der Propaganda. Bochum 2005: Verlag Dr. Dieter Winkler, 9-36, esp. 25-28. This does not entail the assumption that someone (an individual, an institution) intending a specific effect will in fact reach the addressees directly and in the desired way; rather, it should also be expected that various audiences will engage in independent methods of appropriation and in a heroization that is dysfunctional for the propagandists.7Cf. for example Gries: Propageme, 2005, 27; cf. also the study by Gilmour, Colin: “‘Autogramm bitte!’ Heldenverehrung unter deutschen Jugendlichen während des Zweiten Weltkrieges”. In: Denzler, Alexander / Grüner, Stefan / Raasch, Markus (Eds.): Kinder und Krieg. Von der Antike bis in die Gegenwart. Berlin/Boston 2016: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 131-149.

3. Conceptual history

Communications scholar Heinz Starkulla Jr. states that, nowadays, by ‘propaganda’ many can “no longer imagine anything more than the totalitarian control and manipulation of communication that unequivocally arouses revulsion”.8Starkulla jr., Heinz: Propaganda. Begriffe, Typen, Phänomene. Mit einer Einführung von Hans Wagner. Baden-Baden 2015: Nomos, 59. To date, Starkulla jr. has made the most extensive contribution to establishing the conceptual history of propaganda, ibid., 59-233. From a historical perspective, however, this understanding of ‘propaganda’ by no way constitutes a universal phenomenon that transcends time periods. On the contrary, in the more than 400 years of its use, the propaganda concept experienced changing ascriptions of meaning and oscillated between positive and negative connotation depending on the political, religious, or advertising orientation.9The following proceeds on the basis of Starkulla: “Propaganda”, 2015; Bussemer, Thymian: Propaganda. Konzepte und Theorien. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden 2008: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. While Starkulla traces the conceptual history of propaganda, distinguishes elements of a theory on propaganda and offers a typology of (wartime) propaganda in order to free it “from the fetters of a mere martial term” (60), Bussemer writes the history of propaganda primarily as a succession of intellectual discourses and also provides an, albeit brief, typology of different forms of propaganda.

The word, derived from the Latin propagare (spread, scatter, procreate, extend), first appeared as the description of a communication technique in Europe in the early 17th century in connection with Catholic missioning.10For more detail, cf. the overview in Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2008, 26-28; and regarding the religious origin, cf. Starkulla jr.: “Propaganda”, 2015, 64-76. For the actors of the Counter-Reformation, ‘propaganda’ initially described the dissemination, considered desirable, of Catholic dogma, which inescapably had to meet with rejection from Protestants. Martyrs who were willing to give their lives for their faith emerged here as heroic. During the French Revolution, although propaganda increased in importance through the advent of modern mass media, the term continued to invite suspicion of being bound to institutions and fostering conspiratorial activities due to its original proximity to the Catholic church. The liberal Vormärz movement, which sought to disseminate democratic principles, was the first to turn ‘propaganda’ into a “generally used instrument for popularising political interests”.11Bussemer, Thymian: “Propaganda. Theoretisches Konzept und geschichtliche Bedeutung (2013)”. In: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 2013. Online at: http://docupedia.de/zg/Propaganda (accessed 2022-10-26). After the revolution of 1848/49, the propaganda concept was also used in circles of political anarchism. The ‘propaganda of the deed’ formula concealed more or less outright calls for politically motivated acts of ⟶violence, which led to agents of German social democracy replacing the term propaganda with ‘agitation’ for a time.12For more, cf. Schieder, Wolfgang / Dipper, Christoph: “Propaganda”. In: Brunner, Otto / Conze, Werner / Koselleck, Reinhart (Eds.): Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland. Vol. 5. Stuttgart 1984: Klett-Cotta, 69-112, esp. 94-98. In the communist movement, it was primarily Lenin who advocated for a positive connotation of the propaganda concept. The ‘propaganda’ of the party, understood as being enlightening, was designed to indoctrinate and inculcate workers ideologically by means of mass media communication.13For more, cf. Bussemer: “Propaganda. Theoretisches Konzept”, 2013, 3-5. On the seemingly somewhat arbitrary differentiation between the terms ‘propaganda’ and ‘agitation’ with Lenin, cf. Schieder / Dipper: “Propaganda”, 1984, 98-100. The “Hero of (Socialist) Labour”, who has been used as a role model for maximum production performance, also has its beginnings here.14For more detail on this, cf. Project D8 “The Heroization of Labor in China and Russia between 1920 and 1960” of the Sonderforschungsbereich 948 “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms” at the University of Freiburg.

Around the turn of the century, the term propaganda in Germany had detached itself from its political mooring and made inroads into the economic sphere, where it appeared as a synonym for ‘promotion’.15Currently, this appears to be the area in which “heroes” are encountered in Germany with particular frequency. Besides ‘advertisement’ and ‘promotion’, ‘propaganda’ soon became an integral part of economic jargon, which is why the economist Rudolf Seyffert noted at the end of the 1920s that there were “three different expressions for the same term”.16Seyffert, Rudolf: Allgemeine Werbelehre. Stuttgart 1929: Poeschel, 90. During Nazism, there were efforts to transfer the propaganda concept back to the exclusivity of the political realm, which is why a distinction was sought – not always maintained in practice – between ‘political propaganda’ (politische Propaganda), ‘commercial advertisement’ (kommerzielle Werbung), and the negatively connoted ‘Jewish promotion’ (jüdische Reklame) – a conceptual trichotomy that still resonates in German today.17As according to Gries: “Propageme”, 2005, 10f. In practice, the linguistic differentiation is not always maintained. While ‘propaganda’ remained positively connoted in socialist societies even after 1945 in keeping with the Leninist interpretation, in the post-war Federal Republic of Germany, the term was primarily associated with the Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda and its chief, Joseph Goebbels. This persistent connection between Nazism and propaganda points to the politics of memory that have been inherent to the term and the subject since the post-war period: the reference to propaganda – understood as the totalitarian control and dissemination of information by the rulers – could/can also function as an exoneration strategy on the part of the audience; the public could/can imagine itself in hindsight as the ‘victim’ of manipulative or ‘seductive’ propaganda.18As a case study of the post-war period, cf. Anke-Marie Lohmeier’s study on protests against Veit Harlan and the verdict of the court that found Harlan not guilty but the film Jud Süss guilty. Harlan’s defamation and the court’s conviction of a film instead of an individual corresponds to contemporaries’ general need to be absolved of personal responsibility for the crimes of the past. Lohmeier, Anke-Marie: “Propaganda als Alibi. Rezeptionsgeschichtliche Thesen zu Veit Harlans Film ‘Jud Süß’”. In: Przyrembl, Alexandra / Schönert, Jörg (Eds.): “Jud Süß”. Hofjude, literarische Figur, antisemitisches Zerrbild. Frankfurt a. M. / New York 2006: Campus, 201-220.

The diverse associations that the term propaganda evokes until today and the connotations that are linked to it are reflected in scholarly studies. In summarising the state of conceptual debates, Thymian Bussemer states that even after more than seventy years of efforts at systematisation, there is no precise and generally recognised definition of propaganda.19Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2008, 393.

4. Research overview

4.1. The current state of the research

The branch of recent propaganda scholarship espoused here understands propaganda as a specific form of (mass) media communication and not as the communication of specific content. This approach no longer proceeds on the basis of a pejorative, unreflective notion of propaganda that presupposes its high potency, but emphasises – in following British cultural studies – the affordance of propaganda. According to this notion, the audience constitutes an actor in its own right in contrast to the ‘easily influenced masses’ of earlier notions of propaganda.20With a critical perspective on Gustave Le Bon’s theory of the masses, cf. Gries: Propageme, 2005, 15. The communications scholar Gerhard Maletzke was already advocating in the early 1970s to view the aggregate of the people whom propagandists considered important for their respective purposes as the “target group” in the sense of an agglomeration with little structure to it. Maletzke, Gerhard: “Propaganda. Eine begriffskritische Analyse”. In: Publizistik 17.2 (1972), 153-164, esp. 156f. The addressees must be able to classify propaganda as credible within their world view. Whether the propaganda transports factually accurate or false/disingenuous messages becomes less important.21This aspect is emphasised by Stanley, Jason: How Propaganda Works. Princeton 2017: Princeton University Press, 41ff. Hence, propaganda is not characterised by the universal claim to validity; instead, it constitutes merely one promotional communication means among several.22The definition follows Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2008, 32-37; Gries: “Propageme”, 2005, 13 f.; Zimmermann, Clemens: Medien im Nationalsozialismus. Deutschland 1933–1945, Italien 1922–1943, Spanien 1936–1951. Wien et al. 2007: Böhlau, 17-25; Hillmann, Karl-Heinz: “Agitation”. In: Wörterbuch der Soziologie. 5th ed. Stuttgart 2007: Kröner, 12. For the given historical context being examined, specific media landscapes in addition to political and social circumstances must therefore be considered.23Inge Marszolek has convincingly illustrated both aspects using the example of the medium of radio: Marszolek, Inge: “Exploring Nazi Propaganda as Social Practice”. In: Mertelsmann, Olaf (Ed.): Central and Eastern European Media under Dictatorial Rule and in the Early Cold War. Frankfurt a. M. 2011: Peter Lang, 49-60.

As a social situation and specific form of communication, this very broadly understood propaganda concept describes a competition of and for opinions that plays a role in constituting modern – and hence not just totalitarian – societies and includes all forms of advertisement, public relations, and the controlled or even just selective provision of information via media.24Extensive and including further references based on the example of Nazism, cf. Sösemann, Bernd: Propaganda. Medien und Öffentlichkeit in der NS-Diktatur. Vol 1. Stuttgart 2011: Steiner, VII and XL-XLII. Instead of wanting to impose preformed interpretations onto the recipients (even if that certainly is the intent of many propagandists in practice), from a historical-analytical perspective propaganda merely provides communicative efforts for the individual appropriation and interpretation of information.25Cf. Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2013, 10f. When propaganda is effective over a prolonged period of time, this occurs through reciprocal communication between broadcasters and recipients. Propaganda therefore invariably finds itself in an exchange relationship with a counterpart26Thilo Eisermann’s study of the German and French propaganda strategies during the First World War emphasises this aspect. Eisermann, Thilo: Pressephotographie und Informationskontrolle im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Vergleich. Hamburg 2000: Kämpfer, 40 ff., which can be both the competing propaganda of an (ideological) opponent and reactions from the audience.27This is emphasised particularly by Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2008, 30 ff.

Here there is an important interface to studies of heroization processes, for it must be assumed that heroes can only be heroes if they are accepted by an audience. This audience, in turn, is composed of heterogeneous actors who, as admirers or opponents, not only react to hero figures, but actively contribute to the creation of the hero configuration. Propaganda is one form of communication in which this occurs.

4.2. Perspectives for future research

Currently, one of the greatest challenges for propaganda research is reapplying the heavily formalised propaganda concept to specific content.28To that end, Rainer Gries has proposed studying so-called “propagemes”, which he understands as outcomes of long-term propagandistic communication processes. The needs, messages, and interpretations of various actors contribute to the establishment of these processes. Gries: “Propageme”, 2005, 24f. Recent historical studies on propaganda analyse their subject from the perspective of the history of science (Bussemer), the history of culture (Gries et al.), or the political history of war (Eisermann).

Studies that systematically link the heroic and propaganda are still in their beginnings. The connection between these two highly complex subjects should be further clarified through interdisciplinary research: what additional analytical value is to be expected when heroization processes are examined that take place in the context of propaganda and become effective therein? What is characteristic of the hero of propagandistic communication as compared to other forms of heroization? And conversely: what becomes clear(er) about propaganda when asking the question of how propaganda works with heroizations?

The task of (not just) historic research is to investigate which propagandistic messages are communicated through heroes and whether and how these messages reach their audience. Answers to these questions become accessible only through a contextualising analysis that (1) goes beyond examining propagandists’ intentions and the content of the propaganda and (2) also considers the social practice of hero production and (3) understands the audience as a heterogeneous group of actors.29One example is Peter Longerich’s history of a large Nazi propaganda campaign in Wiesbaden in May 1934. Longerich, Peter: “Nationalsozialistische Propaganda”. In: Bracher, Karl Dietrich / Funke, Manfred / Jacobson, Hans-Adolf (Eds.): Deutschland 1933-1945. Neue Studien zur nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft. Bonn 1993: Droste, 291-314, esp. 309f. To be able to fulfil this aspiration, theoretical approaches and methods of various disciplines should be used.

For example, in addition to the specific historical situations, future research needs to contemplate more greatly the inherent laws of the media that are utilised whenever propaganda is made using heroes. These inherent laws determine the potential effects of propaganda as well as the recipients’ scope for action: performative forms of propaganda (such as processions and marches) function differently from oral propaganda (e.g. sermons, speeches, and radio), written propaganda (pamphlets, flyers, books, etc.) and visual propaganda (posters, billboards, illustrated magazines, television, film, memorials, and so on).

5. Case study: War reporters as heroes of Nazism

Investigating heroization processes in situations of propagandistic communication could help connecting the content of hero narratives more precisely to the social practice of their construction. Two examples from the Second World War may illustrate this:

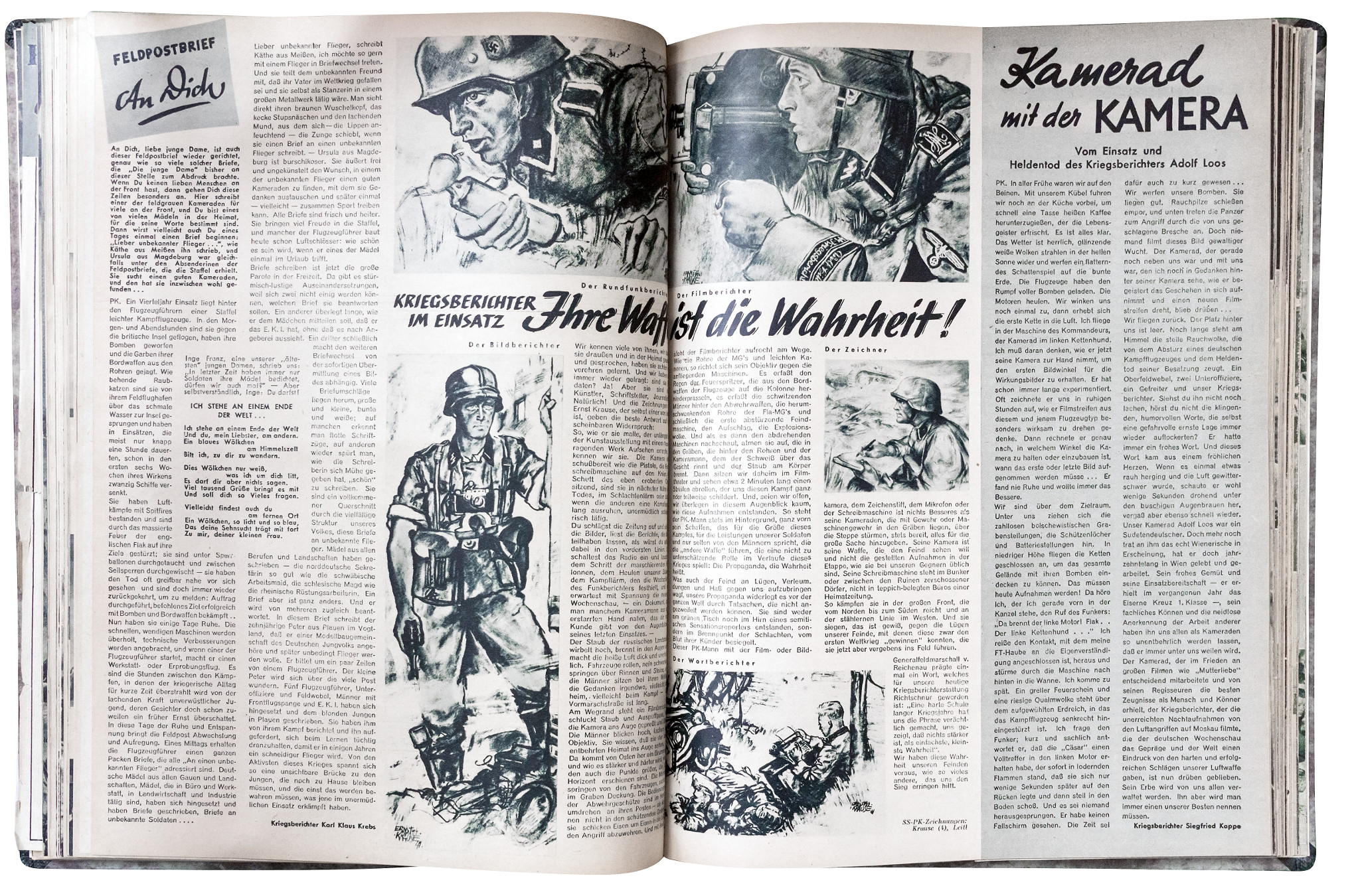

(1) At the time of the Second World War, members of the Propaganda Companies (Propagandakompanien, short PK) were often portrayed in German illustrated magazines as the creators of Nazi heroic stories about the Wehrmacht. Until 1942, there were numerous reports that promoted the authenticity of war reporters’ narratives through their heroization. Such representations of heroic photographers and cameramen who seemingly placed their lives on the line for a successful photograph were able to give greater appeal to their coverage, including coverage of the heroism of German soldiers. For instance, the report “Their weapon is the truth! War reporters in action” in the 25 August 1942 issue of Die junge Dame (The Young Lady) dramatised the work of the Propaganda Companies as heroic (fig. 1). Microphone, camera, typewriter and drawing pad were equated with soldiers’ rifles as “other weapons”. Obliged to be fighters for the truth and the “facts that cannot be denied”, the war reporters found their way into the widely disseminated hero stories of German soldiers.

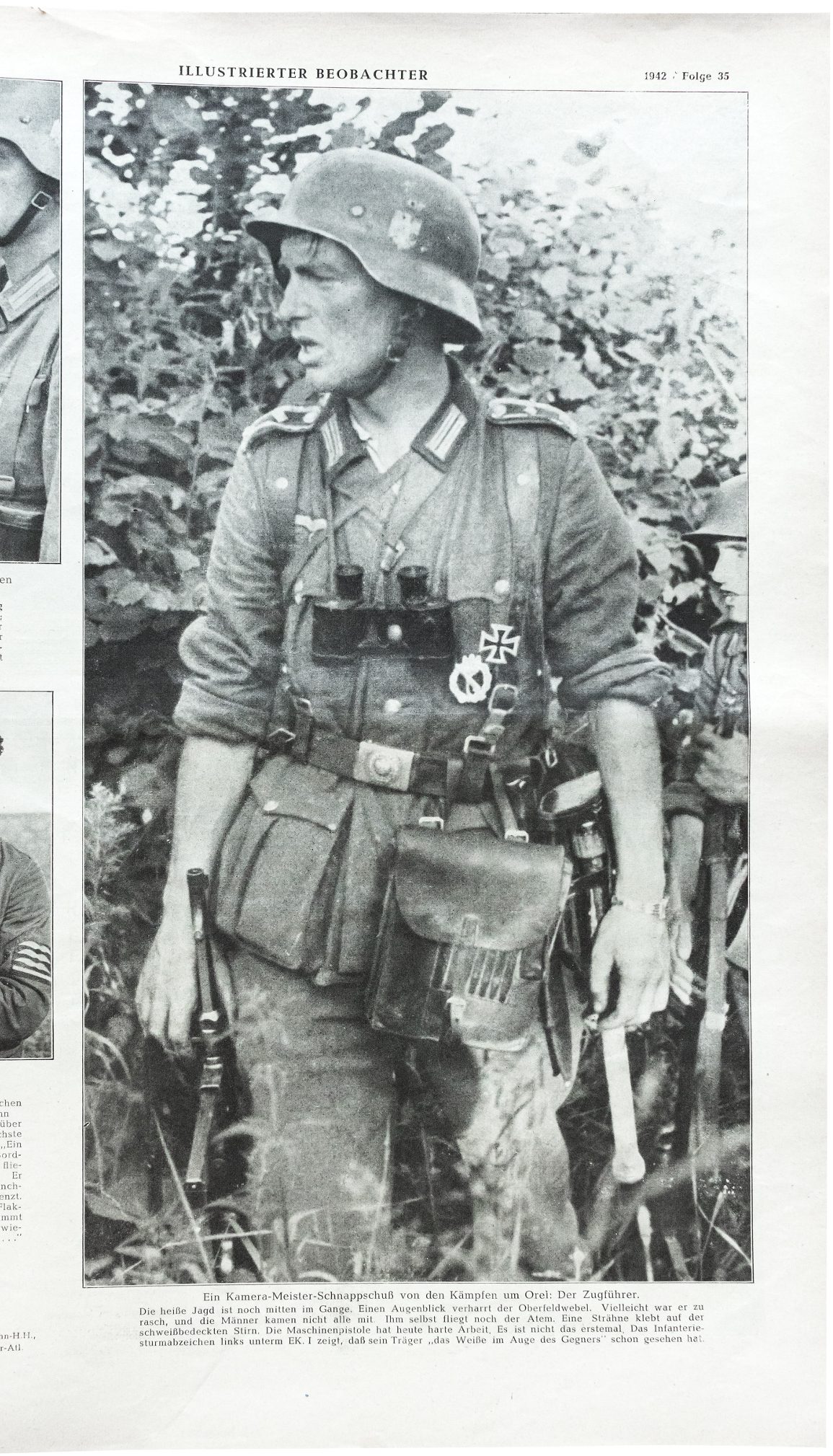

2) Such a picture of the heroic PK members does not correlate with social practice, however. From officials at the Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, which released instructions at daily press conferences as to which reports from the front were to be published30Cf., among others, Arani, Miriam Y.: “Die Fotografien der Propagandakompanien der deutschen Wehrmacht als Quellen zu den Ereignissen im besetzten Polen 1939–1945”. In: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 60.1 (2011), 1-49, esp. 9., to photo lab technicians to editors of the periodicals, a wide array of actors was involved in selecting the motifs, images, and messages to be conveyed. By contrast, in the example (fig. 2), not only is the agency concentrated on the war photographer, but the mention of a “camera master’s snapshot”31Illustrierter Beobachter No. 35, 27 August 1942, 3. at the right moment also reduces this complex process based on a division of labour to one heroic moment.

Even the fuzziness of many of the photographs in Nazi illustrated magazines should not be (mis)understood as proof of an authentic situation; rather, it is a visual strategy of propagandistic hero narration that is to symbolise authenticity, credibility, and resolve when the photographers are in imminent danger. The PK photograph published in the Illustrierter Beobachter (Illustated Observer) on 27 August 1942 shows a heroic “platoon leader” whose infantry assault badge – according to the caption – stood for his having seen into “the whites of the opponent’s eyes”.32Illustrierter Beobachter No. 35, 27 August 1942, 3. Yet the heading “A camera master’s snapshot from the fighting around Oryol: the platoon leader” simultaneously references the heroism of the photographer, who – unlike the soldier – is mentioned by name to the left of the photo. The fuzziness caused by the reproduction of the photograph in the magazine correspond with the word “snapshot” and the danger mentioned in the caption: “The intense hunt is still in full spate.” The heroism of the photographer and the photographed creates a connection between the two and thereby symbolises one facet of the ideological figure of the community of fate of all Germans recurrent in illustrated magazines that is reinforced by the shared war experience.

6. Einzelnachweise

- 1For reasons of terminological consistency with other SFB publications, we use the American English spelling of “heroization” and its derivatives (“to heroize”, “deheroization”, etc.). Cf. in particular von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms: Transformations and Conjunctures from Antiquity to Modernity: Foundational Concepts of the Collaborative Research Centre SFB 948”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 9-16. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/02. For the original publication in German see von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Helden – Heroisierungen – Heroismen. Transformationen und Konjunkturen von der Antike bis zur Moderne. Konzeptionelle Ausgangspunkte des Sonderforschungsbereichs 948”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 1.1 (2013), 7-14. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2013/01/03.

- 2The term “heroes” refers to heroes of all genders. However, remarkably few women found and still find their way into the canon of heroes (not to mention non-binary or transgender persons).

- 3von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms”, 2019, 12.

- 4For more, cf. von den Hoff, Ralf et al.: “Das Heroische in der neueren kulturhistorischen Forschung: Ein kritischer Bericht”. In: H-Soz-Kult, 28.07.2015. Online at: http://www.hsozkult.de/literaturereview/id/forschungsberichte-2216 (accessed 2022-10-26); and von den Hoff et al.: “Helden – Heroisierungen – Heroismen”, 2013.

- 5For more, cf. Protte, Katja: “Das Erbe des Krieges. Fotografien aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg als Mittel nationalsozialistischer Propaganda im ‘Illustrierten Beobachter’ 1926–1939”. In: Fotogeschichte 16.60 (1996), 19-43.

- 6On the temporality aspect, cf. Gries, Rainer: “Zur Ästhetik und Architektur von Propagemen. Überlegungen zu einer Propagandageschichte als Kulturgeschichte”. In: Gries, Rainer / Schmale, Wolfgang (Eds.): Kultur der Propaganda. Bochum 2005: Verlag Dr. Dieter Winkler, 9-36, esp. 25-28.

- 7Cf. for example Gries: Propageme, 2005, 27; cf. also the study by Gilmour, Colin: “‘Autogramm bitte!’ Heldenverehrung unter deutschen Jugendlichen während des Zweiten Weltkrieges”. In: Denzler, Alexander / Grüner, Stefan / Raasch, Markus (Eds.): Kinder und Krieg. Von der Antike bis in die Gegenwart. Berlin/Boston 2016: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 131-149.

- 8Starkulla jr., Heinz: Propaganda. Begriffe, Typen, Phänomene. Mit einer Einführung von Hans Wagner. Baden-Baden 2015: Nomos, 59. To date, Starkulla jr. has made the most extensive contribution to establishing the conceptual history of propaganda, ibid., 59-233.

- 9The following proceeds on the basis of Starkulla: “Propaganda”, 2015; Bussemer, Thymian: Propaganda. Konzepte und Theorien. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden 2008: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. While Starkulla traces the conceptual history of propaganda, distinguishes elements of a theory on propaganda and offers a typology of (wartime) propaganda in order to free it “from the fetters of a mere martial term” (60), Bussemer writes the history of propaganda primarily as a succession of intellectual discourses and also provides an, albeit brief, typology of different forms of propaganda.

- 10For more detail, cf. the overview in Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2008, 26-28; and regarding the religious origin, cf. Starkulla jr.: “Propaganda”, 2015, 64-76.

- 11Bussemer, Thymian: “Propaganda. Theoretisches Konzept und geschichtliche Bedeutung (2013)”. In: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 2013. Online at: http://docupedia.de/zg/Propaganda (accessed 2022-10-26).

- 12For more, cf. Schieder, Wolfgang / Dipper, Christoph: “Propaganda”. In: Brunner, Otto / Conze, Werner / Koselleck, Reinhart (Eds.): Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland. Vol. 5. Stuttgart 1984: Klett-Cotta, 69-112, esp. 94-98.

- 13For more, cf. Bussemer: “Propaganda. Theoretisches Konzept”, 2013, 3-5. On the seemingly somewhat arbitrary differentiation between the terms ‘propaganda’ and ‘agitation’ with Lenin, cf. Schieder / Dipper: “Propaganda”, 1984, 98-100.

- 14For more detail on this, cf. Project D8 “The Heroization of Labor in China and Russia between 1920 and 1960” of the Sonderforschungsbereich 948 “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms” at the University of Freiburg.

- 15Currently, this appears to be the area in which “heroes” are encountered in Germany with particular frequency.

- 16Seyffert, Rudolf: Allgemeine Werbelehre. Stuttgart 1929: Poeschel, 90.

- 17As according to Gries: “Propageme”, 2005, 10f. In practice, the linguistic differentiation is not always maintained.

- 18As a case study of the post-war period, cf. Anke-Marie Lohmeier’s study on protests against Veit Harlan and the verdict of the court that found Harlan not guilty but the film Jud Süss guilty. Harlan’s defamation and the court’s conviction of a film instead of an individual corresponds to contemporaries’ general need to be absolved of personal responsibility for the crimes of the past. Lohmeier, Anke-Marie: “Propaganda als Alibi. Rezeptionsgeschichtliche Thesen zu Veit Harlans Film ‘Jud Süß’”. In: Przyrembl, Alexandra / Schönert, Jörg (Eds.): “Jud Süß”. Hofjude, literarische Figur, antisemitisches Zerrbild. Frankfurt a. M. / New York 2006: Campus, 201-220.

- 19Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2008, 393.

- 20With a critical perspective on Gustave Le Bon’s theory of the masses, cf. Gries: Propageme, 2005, 15. The communications scholar Gerhard Maletzke was already advocating in the early 1970s to view the aggregate of the people whom propagandists considered important for their respective purposes as the “target group” in the sense of an agglomeration with little structure to it. Maletzke, Gerhard: “Propaganda. Eine begriffskritische Analyse”. In: Publizistik 17.2 (1972), 153-164, esp. 156f.

- 21This aspect is emphasised by Stanley, Jason: How Propaganda Works. Princeton 2017: Princeton University Press, 41ff.

- 22The definition follows Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2008, 32-37; Gries: “Propageme”, 2005, 13 f.; Zimmermann, Clemens: Medien im Nationalsozialismus. Deutschland 1933–1945, Italien 1922–1943, Spanien 1936–1951. Wien et al. 2007: Böhlau, 17-25; Hillmann, Karl-Heinz: “Agitation”. In: Wörterbuch der Soziologie. 5th ed. Stuttgart 2007: Kröner, 12.

- 23Inge Marszolek has convincingly illustrated both aspects using the example of the medium of radio: Marszolek, Inge: “Exploring Nazi Propaganda as Social Practice”. In: Mertelsmann, Olaf (Ed.): Central and Eastern European Media under Dictatorial Rule and in the Early Cold War. Frankfurt a. M. 2011: Peter Lang, 49-60.

- 24Extensive and including further references based on the example of Nazism, cf. Sösemann, Bernd: Propaganda. Medien und Öffentlichkeit in der NS-Diktatur. Vol 1. Stuttgart 2011: Steiner, VII and XL-XLII.

- 25Cf. Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2013, 10f.

- 26Thilo Eisermann’s study of the German and French propaganda strategies during the First World War emphasises this aspect. Eisermann, Thilo: Pressephotographie und Informationskontrolle im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Vergleich. Hamburg 2000: Kämpfer, 40 ff.

- 27This is emphasised particularly by Bussemer: “Propaganda”, 2008, 30 ff.

- 28To that end, Rainer Gries has proposed studying so-called “propagemes”, which he understands as outcomes of long-term propagandistic communication processes. The needs, messages, and interpretations of various actors contribute to the establishment of these processes. Gries: “Propageme”, 2005, 24f.

- 29One example is Peter Longerich’s history of a large Nazi propaganda campaign in Wiesbaden in May 1934. Longerich, Peter: “Nationalsozialistische Propaganda”. In: Bracher, Karl Dietrich / Funke, Manfred / Jacobson, Hans-Adolf (Eds.): Deutschland 1933-1945. Neue Studien zur nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft. Bonn 1993: Droste, 291-314, esp. 309f.

- 30Cf., among others, Arani, Miriam Y.: “Die Fotografien der Propagandakompanien der deutschen Wehrmacht als Quellen zu den Ereignissen im besetzten Polen 1939–1945”. In: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 60.1 (2011), 1-49, esp. 9.

- 31Illustrierter Beobachter No. 35, 27 August 1942, 3.

- 32Illustrierter Beobachter No. 35, 27 August 1942, 3.

7. Selected literature

- Bussemer, Thymian: “Propaganda. Theoretisches Konzept und geschichtliche Bedeutung”. In: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 2013. Online at: http://docupedia.de/zg/Propaganda (accessed 2022-10-26).

- Bussemer, Thymian: Propaganda. Konzepte und Theorien. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden 2008: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Daniel, Ute / Siemann, Wolfram (Eds.): Propaganda. Meinungskampf, Verführung und politische Sinnstiftung (1789–1989). Frankfurt a. M. 1994: Fischer Taschenbuch.

- Diesener, Gerald / Gries, Rainer (Eds.): Propaganda in Deutschland. Zur Geschichte der politischen Massenbeeinflussung im 20. Jahrhundert. Darmstadt 1996: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Gries, Rainer: “Zur Ästhetik und Architektur von Propagemen. Überlegungen zu einer Propagandageschichte als Kulturgeschichte”. In: Gries, Rainer / Schmale, Wolfgang (Eds.): Kultur der Propaganda. Bochum 2005: Winkler, 9-36.

- Gries, Rainer / Satjukow, Silke (Eds.): Sozialistische Helden. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Propagandafiguren in Osteuropa und der DDR. Berlin 2002: Links.

- Kirchner, Alexander / Doering-Manteuffel, Sabine: “Propaganda”. In: Historisches Wörterbuch der Rhetorik 7. Tübingen 2005: Niemeyer, cl. 266-290.

- Krüger-Saß, Susen: “Propaganda”. In: Fleckner, Uwe et al. (Eds.): Handbuch der politischen Ikonographie. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. München 2011: Beck, 266-273.

- Maletzke, Gerhard: “Propaganda. Eine begriffskritische Analyse”. In: Publizistik 17.2 (1972), 153-164.

- Marszolek, Inge: “Exploring Nazi Propaganda as Social Practice”. In: Mertelsmann, Olaf (Ed.): Central and Eastern European Media under Dictatorial Rule and in the Early Cold War. Frankfurt a. M. 2011: Lang, 49-60.

- Schieder, Wolfgang / Dipper, Christoph: “Propaganda”. In: Brunner, Otto / Conze, Werner / Koselleck, Reinhart (Eds.): Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland. Vol. 5. Stuttgart 1984: Klett-Cotta, 69-112.

- Sösemann, Bernd: Propaganda. Medien und Öffentlichkeit in der NS-Diktatur. Vol. 1. Stuttgart 2011: Steiner.

- Starkulla jr., Heinz: Propaganda. Begriffe, Typen, Phänomene. Mit einer Einführung von Hans Wagner. Baden-Baden 2015: Nomos.

- Tischer, Anuschka: “Propaganda”. In: Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit 10. Stuttgart 2009: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, cl. 452-456.

- Zimmermann, Clemens: Medien im Nationalsozialismus. Deutschland 1933–1945, Italien 1922–1943, Spanien 1936–1951. Wien et al. 2007: Böhlau.

8. List of images

- 1„Ihre Waffe ist die Wahrheit! Kriegsberichter im Einsatz“, in: Die junge Dame, 10. Jahrgang, Nr. 17, 25. August 1942, 2f. Zeichnungen: SS-PK Krause (4 Bilder), SS-PK Leitl (1 Bild).Quelle: Fotografische Reproduktion von Vera Marstaller und Steffen DüllLizenz: Zitat eines urheberrechtlich geschützten Werks (§ 51 UrhG)

- 2„Ein Kamera-Meister-Schnappschuß von den Kämpfen um Orel: Der Zugführer.“ (Bildunterschrift rechts), in: Illustrierter Beobachter, 17. Jahrgang, Nr. 35, 27. August 1942, 3. Foto: PK Lachmann (Heinrich Hoffmann)Quelle: Fotografische Reproduktion von Vera Marstaller und Steffen DüllLizenz: Zitat eines urheberrechtlich geschützten Werks (§ 51 UrhG)