- Version 1.0

- published 24 June 2024

Table of content

1. Introduction / definition

‘Single combat’ describes the conflict between two adversaries and, in the narrower sense, the struggle between a human and another living being that either directly involves physical force or that occurs indirectly through the application of individually usable tools or accessories. Single combat (sometimes also referred to as ‘duel’) needs to be distinguished from mass and team combat, which, just like war, can be understood as “nothing but a duel on a larger scale” (Clausewitz). Athletic and martial, armed, violent and physical, regulated and spontaneous conflicts, as well as the (ritualised) duel, are all practices of single combat. As one form of agonal conflict, single combat can be associated with ⟶heroizations, if the combatant who initially appears weaker prevails and thereby achieves the extraordinary, if he or she is acting in the interests of a community and/or is ⟶adored as a ⟶hero (because of that). In addition, single combat in itself can be regarded as a heroic practice. As a ⟶heroic deed, single combat is a persistent topos and appears as a practice and a subject portrayed in various ⟶media since the time of the early advanced civilisations in the Near East, in ancient Greece and Rome, in the Middle Ages and in the modern period (in the latter primarily in the form of the ritualised duel). (vdH)1This English translation is based on the German article ⟶Zweikampf in Compendium heroicum from January 2018. Parts written by Ralf von den Hoff appear with the initials ‘vdH’ and parts written by Stefan Tilg with ‘Tilg’.

2. Antiquity

2.1. Literature review

Scholarship on the subject of the duel hardly acknowledges ancient examples of single combat and lacks a summary overview of its forms and functions in antiquity.2Regarding the Bronze Age cultures of Mesopotamia and Anatolia, see Ahlberg, Gudrun: Fighting on Land and Sea in Greek Geometric Art. Stockholm 1971: Aström, 71-85; Berwanger, Monika / Helmer, Matthias: “Zweikampf/Ringkampf”. In: Das Wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet, 2011. Online at: https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/stichwort/35598 (accessed on 18.06.2024). For the Bronze Age, Gilgamesh’s struggles have garnered attention most of all, as last summarised by Steymans 2010.3Steymans, Hans Ulrich: Gilgamesch. Ikonographie eines Helden. Fribourg 2010: Academic Press. Regarding the visual culture of that Age, the especially frequent ‘animal combat scenes’ (combat between a man/hero and an animal) have been explored.4Rohn, Karin: “Tierkampfszene”. In: Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 14. Boston 2014-2016: de Gruyter, 6-8. For ancient Greece, there is intensive research on battle scenes and their typology within the ⟶Homeric epics.5Fenik, Bernhard: Typical Battle Scenes in the Iliad. Studies in the Narrative Techniques of Homeric Battle Description. Wiesbaden 1968: Steiner; Latacz, Joachim: Kampfparänese, Kampfdarstellung und Kampfwirklichkeit in der Ilias, bei Kallinos und Tyrtaios. Munich 1977: Beck; van Wees, Hans: Status Warriors, Violence, and Society in Homer and History. Amsterdam 1992: Gieben; Stoevesandt, Magdalene: Feinde – Gegner – Opfer. Zur Darstellung der Troianer in den Kampfszenen der Ilias. Basel 2004: Schwabe; succinct overview in Mueller, Martin: “Duels”. In: Finkelberg, Margalit (Ed.): The Homer Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Oxford 2011: Wiley-Blackwell, 223-224. These studies discuss the relation of typical scenes of single combat to notions of the past,6Hellmann, Oliver: Die Schlachtszenen der Ilias. Das Bild des Dichters vom Kampf in der Heroenzeit. Stuttgart 2000: Steiner. to the establishment of the Greek hoplite phalanx as the predominant form of mass combat from the 8th/7th century BC onward,7Latacz: Kampfparänese, 1977; Fortassier, Pierre: “A propos de l’emploi du duel chez Homère”. In: Revue des Etudes Grècques 102 (1989), 183-89; van Wees, Hans: “The Homeric Way of War. The ‘liad’ and the Hoplite Phalanx”. In: Greece & Rome 41 (1994) 1-18; 131-155; Hanson, Victor Davis: Hoplites. The Classical Greek Battle Experience. London 1993; Routledge; Cartledge, Paul: “La nascita degli opliti e l’organizzazione militare”. In: Settis, Salvatore (Ed.): I Greci. Storia, cultura, arte, società, 2, 1. Torino 1996: Enaudi, 681-714; more recently: Kagan, Donald / Viggiano, Gregoy F. (Eds.): Men of Bronze. Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece. Princeton 2013: Princeton University Press; Schwartz, Adam: Reinstating the Hoplite. Arms, Armour and Phalanx Fighting in Archaic and Classical Greece. Stuttgart 2013: Steiner. and to ancient warfare within a greater chronological framework.8Lendon, Jon E.: Soldiers & Ghosts. A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity. New Haven 2005: Yale University Press; Sabin, Philip (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare. Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press. Literature on Virgil’s Aeneid emphasises not only its successorship to Homer, but also its particular reference to the Roman tradition of the spolia opima, i.e. the enemy field commander’s weapons won in single combat.9Martino, John: “Single combat and the Aeneid”. In: Arethusa 41 (2008), 411-444; Katz, Rebecca: “Combat, single”. In: Thomas, Richard F. (Ed.): The Virgil Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Chichester 2013: Wiley-Blackwell, 286-287. In addition, instances of single combat have been characterised as an archetype of Indo-European heroic epic.10As is explained by West, Martin L.: Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford 2007: Oxford University Press. Udwin 1999 sees in them an identifying feature of a premodern ‘epic culture’11Udwin, Victor M.: Between Two Armies. The Place of the Duel in Epic Culture. Leiden 1999: Brill. going beyond the literary. However, too little attention is given to the fact that literary sources do not necessarily reflect historical reality or even mentality. Complementing Livy’s recounts of single combat in Roman history, Oakley 1985 has outlined the historical practice of formalised single combat in the army of the Roman Republic and, in brief, that of Greece and other cultures.12Oakley, Stephen P.: “Single Combat in the Roman Republic”. In: Classical Quarterly 35 (1985), 392-410. Regarding Livy, see: Fries, Jutta: Der Zweikampf. Historische und literarische Aspekte seiner Darstellung bei T. Livius. Königstein im Taunus 1985: Hain.

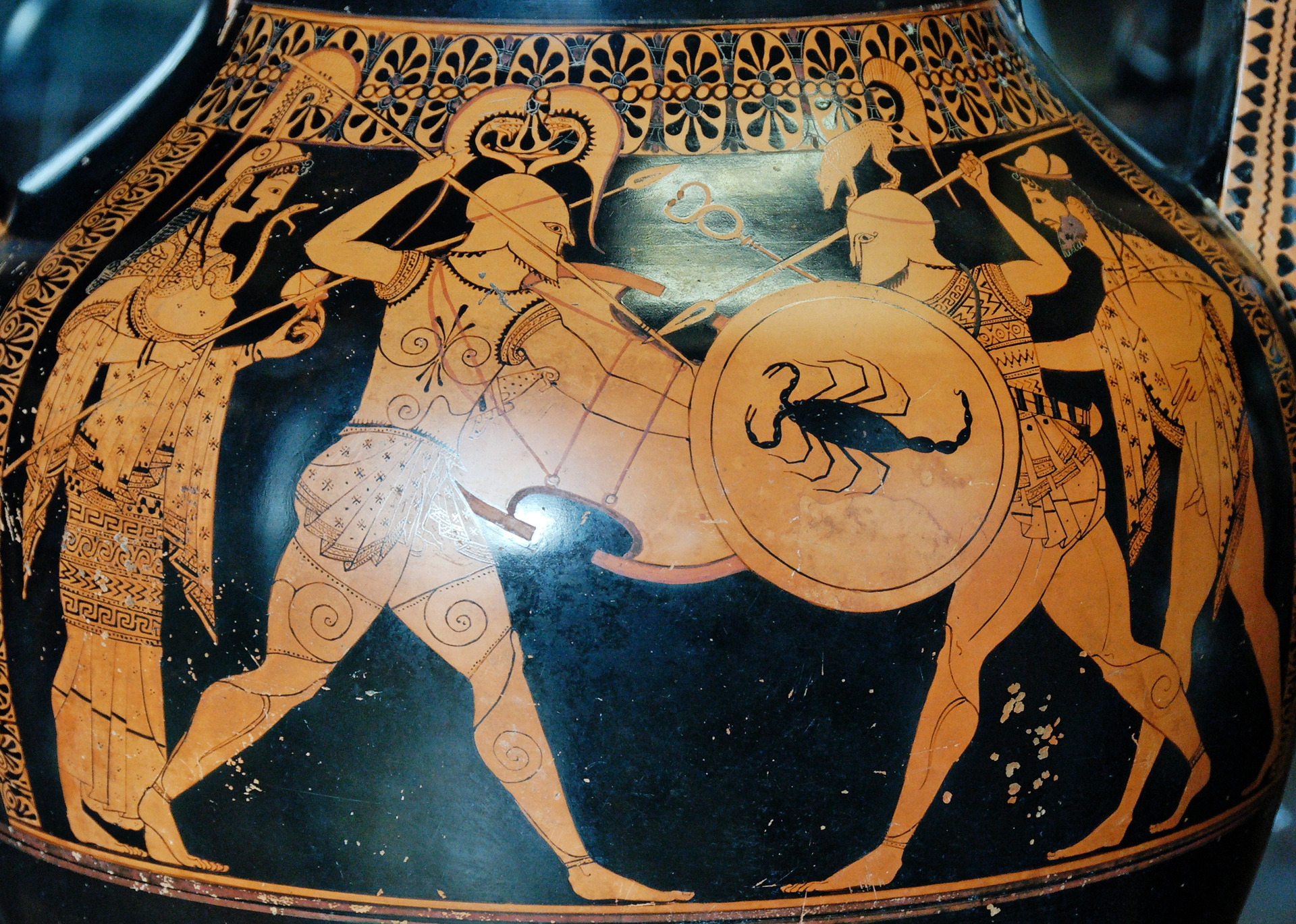

For visual records of the 2nd millennium BC in Minoan and Mycenaean Greece, Vonhoff 2008 has discerned that the superior fighter and victor, either on foot or in a chariot, became a common stereotype in images of single combat.13Vonhoff, Christian: Darstellungen vom Kampf und Krieg in der minoischen und mykenischen Kultur. Rahden 2008: Leidorf. Combat scenes in imagery from the early period of Greek history in the 8th century BC have been studied systematically,14Ahlberg: Fighting, 1971; Grunwald, Christiane: “Frühe attische Kampfdarstellungen”. In: Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologice 15 (1983) 155-203; see also Haug, Annette: Die Entdeckung des Körpers. Körper- und Rollenbilder im Athen des 8. und 7. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Berlin 2012: de Gruyter, 249-295. with particular attention given to those in the extensive corpus of paintings on Attic pottery of the 6th and 5th centuries BC.15Mennenga, Ionna: Untersuchung zur Komposition und Deutung homerischer Zweikampfszenen in der griechischen Vasenmalerei. Berlin 1976: Freie Universität; Knittlmayer, Brigitte: Die attische Aristrokatie und ihre Helden. Untersuchungen zu Darstellungen des trojanischen Sagenkreises im 6. und frühen 5. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Heidelberg 1997: Verlag Archäologie und Geschichte; Ellinghaus, Christian: Aristokratische Leitbilder – demokratische Leitbilder. Kampfdarstellungen auf athenischen Vasen in archaischer und frühklassischer Zeit. Münster 1997: Scriptorium; Recke, Matthias: Gewalt und Leid. Das Bild des Kriegers bei den Athenern im 6. und 5. Jh. v. Chr. Istanbul 2002: Yayinkari; see even the early examinations in Bie, Oscar: Kampfgruppen und Kämpfertypen in der Antike. Berlin 1891: Mayer & Müller. Online at: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bie1891 (accessed on 18.06.2024); Meier, Paul J.: “Das Schema der Zweikämpfe auf den älteren griechischen Vasenbildern”. In: Rheinisches Museum 37 (1882), 343-354. Even in the context of more extensive scenes of mass combat from Greek mythology and everyday life, a continuity of the Homeric-aristocratic model of armed single combat, that can be described as anachronistic, can be seen lasting through to the 5th century BC. This has been interpreted as a sign of an idealising or heroizing representation of combat that emphasised individual experiences, the capability of the individual and the ‘Homeric’ habitus in contrast with mass combat.16Ellinghaus: Aristokratische Leitbilder, 1997; Knittlmayer: Aristokratie, 1997, 68-69; Hölscher, Tonio: “Images of War in Greece and Rome: Between Military Practice, Public Memory, and Cultural Symbolism”. In: The Journal of Roman Studies 93 (2003), 1-17, 4-6; Hölscher, Tonio: La vie des images grecques. Sociétés de statues, rôles des artistes et notions esthétiques dans l’art grec ancien. Paris 2015: Hazan, 55-56.

More recent studies examine motifs of ⟶violence and superiority in portrayals of combat from the 6th and 5th centuries BC17Muth, Susanne: Gewalt im Bild. Das Phänomen der medialen Gewalt im Athen des 6. und 5. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Berlin 2008: de Gruyter; see also Recke: Gewalt und Leid, 2002, 11-74; 216-218; 223-228., as well as the visual formulae found in images of battle (sometimes also resolved in single combat) from the Hellenistic period and Imperial Rome, all within their ideological contexts.18Hölscher: “Images of War”, 2003; Faust, Stefan: Schlachtenbilder der römischen Kaiserzeit. Erzählerische Darstellungskonzepte in der Reliefkunst von Traian bis Septimius Severus. Rahden 2012: Leidorf; Pirson, Felix: Ansichten des Krieges: Kampfreliefs klassischer und hellenistischer Zeit im Kulturvergleich. Wiesbaden 2014: Reichert. Research on sporting bouts in Greek antiquity19See Scanlon, Thomas Francis: Sport in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press. and on gladiator fights in Rome20See Mann, Christian: Die Gladiatoren. Munich 2013: Beck. is extensive. (vdH/Tilg)

2.2. Phenomena and forms of (re)presentation

2.2.1. Practices

Antiquity did not know the modern concept of the duel (of honour). Single combat was either, as is often the case in Greco-Roman epics, integrated as one episode into a war scenario, or, as in the Babylonian-Assyrian Gilgamesh epic or in the Indian Ramayana epic, incorporated into the ⟶narrative of a hero’s adventurous life. As a historical practice of aristocratic combatants, it likely played a certain role in military conflicts before the introduction of mass combat techniques, such as the hoplite phalanx in ca. 700 BC.21Oakley: “Single Combat”, 1985, 392-410. While it quickly disappeared thereafter in Greece – outside of athletic agonistics – with few exceptions (cf. 2.2.3. Visual culture below), it persisted in Rome until the end of the Republic as a formalised ritual in which ambitious fighters could earn their military spurs.22Oakley: “Single Combat”, 1985. Although still significantly elaborated in works of literature, such as in Virgil’s Aeneid23Martino: “Single Combat”, 2008., there are substantially fewer accounts of the practice of spolia opima, in which a Roman military leader removed his equally high-ranking opponent’s armour in single combat, thereby ending the war. The bitterly waged civil war and the diminishment of aristocratic individualism due to the subsequent Principate essentially ended the tradition of single combat in the Roman army.24Oakley: “Single combat”, 1985, 410.

There likely were military single combat practices also among other peoples. Diodorus (Bibliotheca historica 17.6) recounts how Darius excelled among the Persians as a candidate for the royal throne through a successful bout of single combat with a representative of the enemy army. According to Tacitus (Germania 10.3), the Germanic peoples held contests of single combat between one of their best fighters and a prisoner from the party waging war against them in order to prophesy on the further course of the war. Gregory of Tours (Historia Francorum 2.2) reported in the 6th century AD that the Vandals and Alemanni invading Spain resolved their conflicts over territory in single combat.

Historical practices of single combat in a wider sense also included the gladiatorial system and athletic competitions. Roman gladiator bouts were orchestrated as ritualised single combat; in the Greek East of the Roman Empire, gladiators were often compared with mythical heroes.25Mann, Christian: “Um keinen Kranz, um das Leben kämpfen wir!” Gladiatoren im Osten des Römischen Reiches und die Frage der Romanisierung. Berlin 2011: Verlag Antike. In sport, single combat was typical in wrestling, boxing and the pankration. The heroization of athletes precisely of these disciplines is common.26Bentz, Martin / Mann, Christian: “Zur Heroisierung von Athleten”. In: von den Hoff, Ralf / Schmidt, Stefan (Eds.): Konstruktionen von Wirklichkeit. Bilder im Griechenland des 5. und 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Stuttgart 2001: Steiner, 225-240; François de Polignac: “Addendum to François de Polignac, ‘Athletes, statues and tyrants’. A few more thoughts on heroized athletes”. In: Thomas F. Scanlon (Ed.): Sport in the Greek and Roman worlds I. Early Greece, the Olympics, and contests. Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press, 112-116; see also Joseph Fontenrose: “The hero as athlete”. In: California Studies in Classical Antiquity, 1 (1968), 73-104. (vdH/Tilg)

2.2.2. Literature

In literature, the heroic epic is the typical ⟶genre for the portrayal of single combat. As West 2007 writes, “[n]othing is more characteristic of heroic narrative than accounts of armed encounters between individuals”.27West: Indo-European Poetry, 2007, 486. In between the 3rd and 1st millennia BC, single combat was a common part of the narrative repertoire in the early advanced civilisations of Egypt, the Levant, Anatolia and Mesopotamia.28Berwanger, Monika / Helmer, Matthias: “Zweikampf/Ringkampf”. In: Das Wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet, 2011. Online at: https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/stichwort/35598 (accessed on 18.06.2024). Exceptional single combat victories over dangerous animals or hybrids were attributed to rulers most of all. Before he becomes king of Judah, young David, for example, kills the military leader and giant Goliath with a sling (1 Samuel 17). In the Gilgamesh epic, passed down since the 3rd millennium BC,29Maul, Stefan M.: Das Gilgamesch-Epos. Munich 2005: Beck; Sallaberger, Walther: Das Gilgamesch-Epos. Mythos, Werk und Tradition. Munich 2008: Beck. the eponymous king of Uruk, together with Enkidu, defeats the giant guardian of the cedar forest, Humbaba, first in physical wrestling (tablet V 125-127), then through a sword thrust (table V 261-267). Like a butcher, he kills the Bull of Heaven through a sword thrust to its neck (tablet VI 139-146), which had been dispatched by the goddess Ishtar and sent masses of Uruk’s youth to their deaths (tablet VI 119-127). He overpowers lions with an axe and a sword (tablet IX 9-18). His human helper Enkidu, on the other hand, he confronts in a barehanded athletic agon (tablet II 100-115). Homer’s epic The Iliad (8th/7th century BC) often depicts the heroes in mass combat (see ⟶Homeric heroes). However, these scenes are consistently resolved in single combat (Greek: monomachia),30Latacz: Kampfparänese, 1977. highlighting the outstanding achievements of individual warriors (Greek: aristeia, from aristeuein for “to be the best, to excel among others”; the concept entered descriptive philological vocabulary as ‘aristeia’ for a typical element of epic narrative).31Krischer, Tilman: Formale Konventionen der homerischen Epik. Munich 1971: Beck, 13-89. Single combat therefore seems to outshine historical contemporary fighting techniques, which allows the agonal, individual capabilities of the heroes to stand out.32Latacz: Kampfparänese, 1977. Due to its presence in Homer’s works, single combat also takes on heroic features.33Hellmann: Schlachtszenen, 2000. Without exception, the opponents are identified by name and individually characterised. They often explicitly challenge each other on the battlefield and engage in dialogue – in the exceptional case of Glaucus and Diomedes (Iliad 6.120-232), this leads to the two adversaries discovering their common ancestry and abandoning their fight. Except for more or less coincidental encounters on the battlefield, single combat can also be held during lulls in the fighting under certain formal conditions. In the Iliad 7.54-91, Hector for example calls on the Greeks to send out their bravest fighter to engage him in single combat. The subsequent fight with Ajax ends undecided and has more the character of a tournament than that of a deciding act. In Iliad 3.67-75, however, Paris and Menelaus plan a genuine deciding bout of single combat when they agree that the victor would receive Helena and thus win the Trojan War. The agreement is validated with sacrifices and oaths of both parties, but ultimately nullified through Aphrodite’s intervention. The gods also intervene in other incidents of single combat in Homer’s Iliad, which is similar to an extent with the mediaeval bouts of single combat that were held as an ordeal by battle.

The Homeric individualisation of battlefield fighting and the resulting focus on scenes of single combat becomes a model for the Greco-Roman epic overall, such as in Virgil’s Aeneid, where in book 12 Aeneas avenges the killing of Pallas in a final act of single combat with Turnus similarly to Achilles avenging the ⟶death of Patroclus in single combat with Hector. In Virgil’s Aeneid however, the gods do not intervene in the bouts of single combat, whereas in the Iliad, Athena in human form dissuades Hector from fleeing and allows him to accept the challenge of single combat and thereby his downfall. There are individual examples, such as Lucan’s Bellum civile concerning the Roman civil war written during the Neronian period, that privilege the collective and anonymous portrayal of battle scenes. On the one hand, these are fed by historiographical traditions and/or, on the other hand, serve a deliberately anti-heroic stance, as is the case especially in Lucan’s work.34Esposito, Paolo: “Eroi e soldati. Osservazioni sulle battaglie in Virgillio e Lucano”. In: Vichiana 10 (1981), 62-90. Against this background, projecting single combat successes onto historical ruler figures constitutes hero approximation in epic form: Aristobulus flattered Alexander the Great by describing his victory over the Indian prince Porus as single combat (Lucian, quomodo historia conscribenda sit 12); Alexander survived the Battle of Granicus reportedly only because he was successful in single combat (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 17, 20, 3-5), and even a decisive single combat with the Persian king Darius has been postulated (Plutarch, Alexander 20, 4-5).

In mythology, single combat against wild monsters or exorbitant individuals is a standard motif, as in the adventures of Heracles, Theseus, Bellerophon or Perseus. Finally, a particular variation of literary single combat is the oratorial debate and poetic duelling (see Froleyks 1973 for a general overview). Such verbal single combat was held as early as in the Iliad, for example in the initial conflict between Agamemnon and Achilles over the prisoner of war, Briseis (1, 121-187; 223-244; 285-303).35See Martin, Richard P.: The Language of Heroes. Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca 1989: Cornell University Press. Later, the formalised verbal agones in drama, especially in Euripides,36Dubischer, Markus: Die Agonszenen bei Euripides. Untersuchungen zu ausgewählten Dramen. Stuttgart 2001: Metzler. the song competitions of bucolic shepherds in Theocritus (Idylls 5, 6, 8, 9) and Virgil (Eclogues 3, 5, 7), and the satirical oratorial debates in Lucian became famous.37Froleyks, Walter J.: Der Agon Logon in der antiken Literatur. Diss. Bonn 1973, 360-381. The anonymously written Certamen Homeri et Hesiodi (The Contest of Homer and Hesiod), the surviving version of which dates from the imperial period, imagines a poetry competition between the oldest Greek poets and thus contributes to their heroization. (vdH/Tilg)

2.2.3. Visual culture

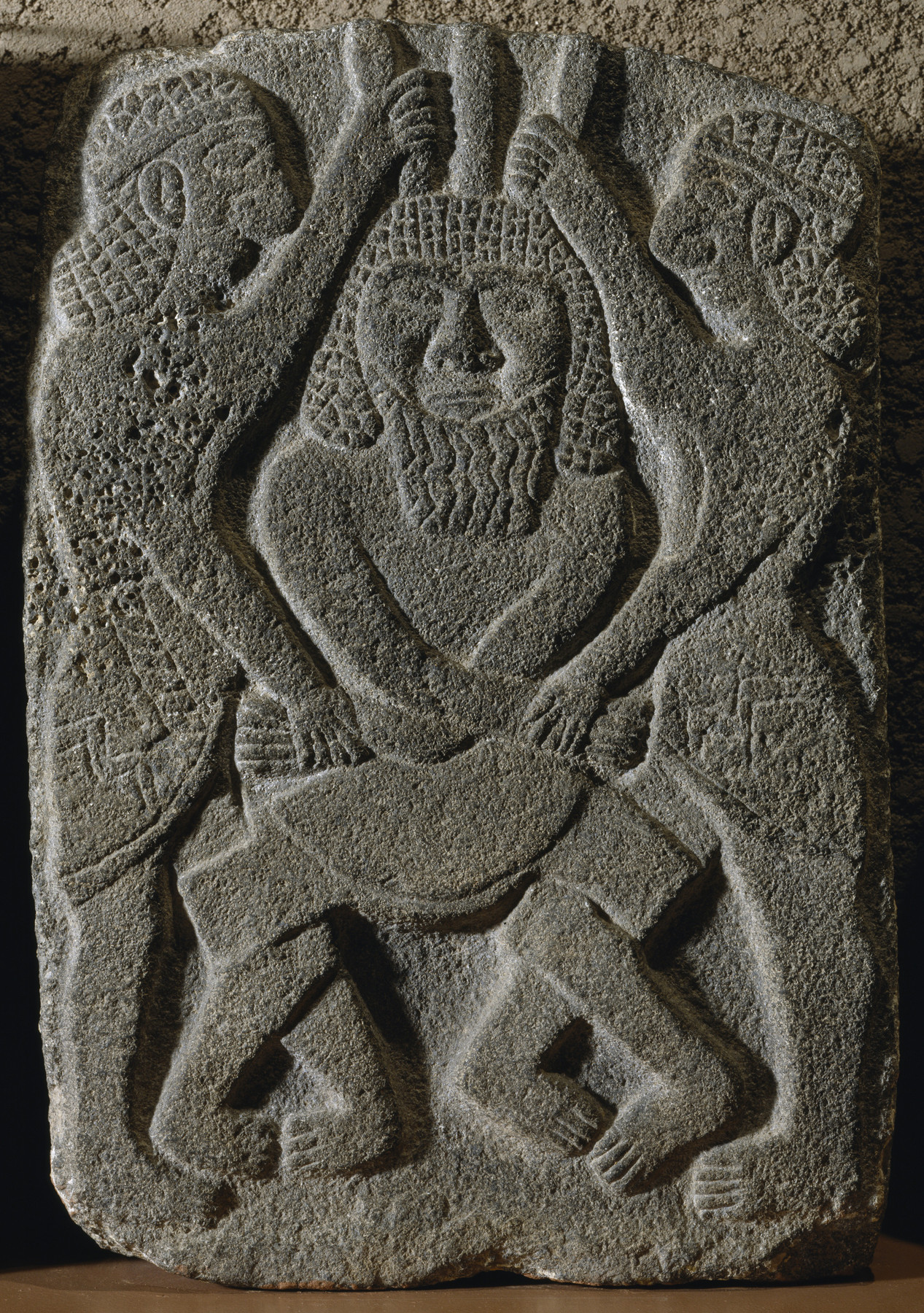

Pictorial art has shown the Egyptian pharaoh primarily as a singular victor over enemy groups.38Schoske, Sylvia: Das Erschlagen der Feinde. Ikonographie und Stilistik der Feindvernichtung im alten Ägypten. Munich 1982: Universität. In Mesopotamia and the Levant, starting in the 3rd millennium BC, the victorious – oftentimes armed – single combat of one or two men over a human or animal opponent (‘animal combat motif’) was a standard motif (‘contest scene’), primarily in glyptics (cylinder seals), but also in reliefs.39Böhmer, Rainer Michael: Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit. Berlin 1965: de Gruyter; Ahlberg: Fighting, 71-85; Rohn, Karin: “Tierkampfszene”. In: Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 14. Boston 2014-2016: de Gruyter, 6-8. While Gilgamesh might be meant in many cases (especially in ‘triads’ with two victorious figures: fig. 1), the corpus – primarily of animal combat scenes – is large and the names of the combatants are not known.40Keel, Othmar: “Die Deutung der Tierkampfzeichen auf den vorderasiatischen Rollsiegeln des 3. Jahrtausends”. In: Keel, Othmar (Ed.): Das Recht der Bilder, gesehen zu werden. Drei Fallstudien zur Methode der Interpretation altorientalischer Bilder. Fribourg 1992: Universitätsverlag; Steymans, Hans Ulrich: Gilgamesch. Ikonographie eines Helden. Fribourg 2010: Academic Press. In Minoan and Mycenaean Greece, scenes of single combat waged on foot, using chariots or while hunting appeared in various pictorial media (fig. 2).41Ahlberg: Fighting, 1971, 71-85; Ahlberg-Cornell, Gudrun: Myth and Epos in Early Greek Art. Stockholm 1971: Aström, 13-15; Vonhoff: Darstellungen von Kampf und Krieg, 2008. See for example the seals depicting scenes of humans engaged in single combat as well as lion combat from Grave Circle A at Mycenae: Arachne Bilddatenbank No. 157232 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/157232); 157230 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/157230); 157233 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/157233); 157237 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/157237) (accessed on 18.06.2024). In Assyria in the 1st millennium BC, the much older lion combat motif gained prominence.42Magen, Ursula: Assyrische Königsdarstellungen – Aspekte der Herrschaft. Eine Typologie. Mainz 1986: von Zabern. The vast number of images shows the legitimising function of displaying one’s power through a victory in single combat even for rulers of the Bronze Age and the early Iron Age. In the 8th century BC, Athens’ elites used scenes of mass combat to decorate their representative ceramic gravestones.43Ahlberg: Fighting 1971; Grunwald, Christiane: “Frühe attische Kampfdarstellungen”. In: Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica 15 (1983), 155-203. At the end of the 8th and in the 7th century BC, the number of depictions of single combat rose in different pictorial media. Images of lion combat (fig. 3) took on an extraordinary character given that lions no longer lived in Greece and had become part of the Heracles myth. At least by the 7th century BC, and then in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, the single combat scene was standard for the depiction of conflict both for mythical heroes such as those of the Homeric epics, like Heracles (fig. 4) and Theseus, as well as for generic or everyday-contemporary conflicts that often blurred with mythical battles (fig. 5).44Hölscher, Tonio: Griechische Historienbilder des 5. und 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Würzburg 1973: Triltsch, 25-30; Recke: Gewalt und Leid, 2002, passim. – Herakles: Wünsche, Raimund / Brinkmann, Vinzenz (Eds.): Herakles – Herkules. Munich 2003: Staatliche Antikensammlungen. – Theseus: Neils, Jenifer: The youthful deeds of Theseus. Rome 1987: Bretschneider. Although in reality warfare was already dominated by the mass phalanx and the collective cavalry battle, there are hardly any accounts of their depictions.45Lorimer, Hilda L.: “The Hoplite Phalanx”. In: The Annual of the British School at Athens 42 (1947) 76-138; van Wees, Hans: “The Development of the Hoplite Phalanx. Iconography and Reality in the 7th Century”. In: van Wees, Hans (Ed.): War and Violence in Ancient Greece. London 2000: . The term Promachos (‘frontline fighter’) was used as an extolling appellation for combatants (Inscripitiones Graecae I3 no. 1240). Even on funerary monuments, such as the Dexileos relief (394 BC), the deceased appears as the victor of a single combat bout despite having fallen in a battle (fig. 6).46Clairmont, Christoph W.: Classical Attical Tombstones. Kilchberg 1993: Akanthus, 143 Cat.No. 2209; Arachne Bilddatenbank No. 48532 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/48532) (accessed on 18.06.2024). All of this shows an anachronistic, heroizing perspective focused on the achievement of the individual,47Hölscher: Historienbilder, 1973: 25-30; Schäfer, Thomas. Andres Agathoi. Studien zum Realitätsgehalt der Bewaffnung attischer Krieger auf Denkmälern klassischer Zeit. Munich 1997: tuduv, 4-9; Ellinghaus: Aristokratische Leitbilder, 1997; see Lendon, Jon E.: Soldiers & Ghosts. A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity. New Haven 2005: Yale University Press. even though the victor’s power and the loser’s status could have been portrayed in manifold ways.48Muth: Gewalt im Bild, 2008. It can additionally be understood as the expression of a more individualised than collective experience of combat.49Knittlmayer: Attische Aristokratie, 1997, 68-69; Hölscher: “Images of War”, 2003, 8-12. Even some depictions of battle and hunting scenes of Alexander the Great and Roman emperors were – at least compositionally – realised as the confrontation between the ‘frontline fighting’ ruler and various opponents, for instance in the ‘Alexander mosaic’ (fig. 7)50Hölscher: Historienbilder 1973, 151-158; Cohen, Ada: The Alexander Mosaic. Stories of Victory and Defeat. Cambridge 1997: Cambridge University Press. or on Roman coins and ‘state reliefs’ (fig. 8).51Faust: Schlachtenbilder der römischen Kaiserzeit, 2012. The ruler was heroized in that he was visually ascribed the central and deciding act in mass combat. There are also extant images of sporting bouts from Egypt and Mesopotamia on seals. The Greco-Roman visual tradition is similarly vast in this respect (fig. 9);52See Wünsche, Raimund (Ed.): Lockender Lorbeer. Sport und Spiel in der Antike. Munich 2004: Staatliche Antikensammlungen. however, heroizing traits are not generally associated with it. The prevalent athletic character of images of single combat, however, gave the single-combat-like visualisation of martial and mythical events an agonal element.53Knittlmayer: Attische Aristokratie, 1997, 69. (vdH/Tilg)

3. Perspectives for future research

A systematic exploration of forms, functions and traditions of single combat in ancient cultures is lacking.54Ahlberg: Fighting, 1971; Ahlberg-Cornell: “Myth and Epos”, 1992; Steymans: Gilgamesch, 2010. Such a study would need to ask most of all whether and if so how the heroizing character in Greek images and texts can be connected to manifestations of single combat in early advanced civilisations, and what role traditions or references played in making those connections.55See Hellmann: Schlachtszenen, 2000. For Greek images of single combat, there is now consensus on their heroic character, but it is unclear how heroization, individualisation and the realisation of each contemporary combat experience interrelate in those heroic depictions.56Hölscher: “Images of War”, 2003. In addition, we need more studies of the reception history of ancient portrayals of single combat primarily with regard to the development of the duel in the modern period. Although gladiator fights have been referred to as models for the modern duel,57Monestier, Martin: Duels. Les combats singuliers des origines à nos jours. Paris 1991: Sand. a more general focus on single combat – as documented and dominant since the Homeric epics – appears to be formative here. That focus is applied because in most cases the point is to single out the agonal in the achievement of the individual and not of the ⟶collective. (vdH/Tilg)

4. References

- 1This English translation is based on the German article ⟶Zweikampf in Compendium heroicum from January 2018. Parts written by Ralf von den Hoff appear with the initials ‘vdH’ and parts written by Stefan Tilg with ‘Tilg’.

- 2Regarding the Bronze Age cultures of Mesopotamia and Anatolia, see Ahlberg, Gudrun: Fighting on Land and Sea in Greek Geometric Art. Stockholm 1971: Aström, 71-85; Berwanger, Monika / Helmer, Matthias: “Zweikampf/Ringkampf”. In: Das Wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet, 2011. Online at: https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/stichwort/35598 (accessed on 18.06.2024).

- 3Steymans, Hans Ulrich: Gilgamesch. Ikonographie eines Helden. Fribourg 2010: Academic Press.

- 4Rohn, Karin: “Tierkampfszene”. In: Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 14. Boston 2014-2016: de Gruyter, 6-8.

- 5Fenik, Bernhard: Typical Battle Scenes in the Iliad. Studies in the Narrative Techniques of Homeric Battle Description. Wiesbaden 1968: Steiner; Latacz, Joachim: Kampfparänese, Kampfdarstellung und Kampfwirklichkeit in der Ilias, bei Kallinos und Tyrtaios. Munich 1977: Beck; van Wees, Hans: Status Warriors, Violence, and Society in Homer and History. Amsterdam 1992: Gieben; Stoevesandt, Magdalene: Feinde – Gegner – Opfer. Zur Darstellung der Troianer in den Kampfszenen der Ilias. Basel 2004: Schwabe; succinct overview in Mueller, Martin: “Duels”. In: Finkelberg, Margalit (Ed.): The Homer Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Oxford 2011: Wiley-Blackwell, 223-224.

- 6Hellmann, Oliver: Die Schlachtszenen der Ilias. Das Bild des Dichters vom Kampf in der Heroenzeit. Stuttgart 2000: Steiner.

- 7Latacz: Kampfparänese, 1977; Fortassier, Pierre: “A propos de l’emploi du duel chez Homère”. In: Revue des Etudes Grècques 102 (1989), 183-89; van Wees, Hans: “The Homeric Way of War. The ‘liad’ and the Hoplite Phalanx”. In: Greece & Rome 41 (1994) 1-18; 131-155; Hanson, Victor Davis: Hoplites. The Classical Greek Battle Experience. London 1993; Routledge; Cartledge, Paul: “La nascita degli opliti e l’organizzazione militare”. In: Settis, Salvatore (Ed.): I Greci. Storia, cultura, arte, società, 2, 1. Torino 1996: Enaudi, 681-714; more recently: Kagan, Donald / Viggiano, Gregoy F. (Eds.): Men of Bronze. Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece. Princeton 2013: Princeton University Press; Schwartz, Adam: Reinstating the Hoplite. Arms, Armour and Phalanx Fighting in Archaic and Classical Greece. Stuttgart 2013: Steiner.

- 8Lendon, Jon E.: Soldiers & Ghosts. A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity. New Haven 2005: Yale University Press; Sabin, Philip (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare. Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- 9Martino, John: “Single combat and the Aeneid”. In: Arethusa 41 (2008), 411-444; Katz, Rebecca: “Combat, single”. In: Thomas, Richard F. (Ed.): The Virgil Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Chichester 2013: Wiley-Blackwell, 286-287.

- 10As is explained by West, Martin L.: Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford 2007: Oxford University Press.

- 11Udwin, Victor M.: Between Two Armies. The Place of the Duel in Epic Culture. Leiden 1999: Brill.

- 12Oakley, Stephen P.: “Single Combat in the Roman Republic”. In: Classical Quarterly 35 (1985), 392-410. Regarding Livy, see: Fries, Jutta: Der Zweikampf. Historische und literarische Aspekte seiner Darstellung bei T. Livius. Königstein im Taunus 1985: Hain.

- 13Vonhoff, Christian: Darstellungen vom Kampf und Krieg in der minoischen und mykenischen Kultur. Rahden 2008: Leidorf.

- 14Ahlberg: Fighting, 1971; Grunwald, Christiane: “Frühe attische Kampfdarstellungen”. In: Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologice 15 (1983) 155-203; see also Haug, Annette: Die Entdeckung des Körpers. Körper- und Rollenbilder im Athen des 8. und 7. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Berlin 2012: de Gruyter, 249-295.

- 15Mennenga, Ionna: Untersuchung zur Komposition und Deutung homerischer Zweikampfszenen in der griechischen Vasenmalerei. Berlin 1976: Freie Universität; Knittlmayer, Brigitte: Die attische Aristrokatie und ihre Helden. Untersuchungen zu Darstellungen des trojanischen Sagenkreises im 6. und frühen 5. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Heidelberg 1997: Verlag Archäologie und Geschichte; Ellinghaus, Christian: Aristokratische Leitbilder – demokratische Leitbilder. Kampfdarstellungen auf athenischen Vasen in archaischer und frühklassischer Zeit. Münster 1997: Scriptorium; Recke, Matthias: Gewalt und Leid. Das Bild des Kriegers bei den Athenern im 6. und 5. Jh. v. Chr. Istanbul 2002: Yayinkari; see even the early examinations in Bie, Oscar: Kampfgruppen und Kämpfertypen in der Antike. Berlin 1891: Mayer & Müller. Online at: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bie1891 (accessed on 18.06.2024); Meier, Paul J.: “Das Schema der Zweikämpfe auf den älteren griechischen Vasenbildern”. In: Rheinisches Museum 37 (1882), 343-354.

- 16Ellinghaus: Aristokratische Leitbilder, 1997; Knittlmayer: Aristokratie, 1997, 68-69; Hölscher, Tonio: “Images of War in Greece and Rome: Between Military Practice, Public Memory, and Cultural Symbolism”. In: The Journal of Roman Studies 93 (2003), 1-17, 4-6; Hölscher, Tonio: La vie des images grecques. Sociétés de statues, rôles des artistes et notions esthétiques dans l’art grec ancien. Paris 2015: Hazan, 55-56.

- 17Muth, Susanne: Gewalt im Bild. Das Phänomen der medialen Gewalt im Athen des 6. und 5. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Berlin 2008: de Gruyter; see also Recke: Gewalt und Leid, 2002, 11-74; 216-218; 223-228.

- 18Hölscher: “Images of War”, 2003; Faust, Stefan: Schlachtenbilder der römischen Kaiserzeit. Erzählerische Darstellungskonzepte in der Reliefkunst von Traian bis Septimius Severus. Rahden 2012: Leidorf; Pirson, Felix: Ansichten des Krieges: Kampfreliefs klassischer und hellenistischer Zeit im Kulturvergleich. Wiesbaden 2014: Reichert.

- 19See Scanlon, Thomas Francis: Sport in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press.

- 20See Mann, Christian: Die Gladiatoren. Munich 2013: Beck.

- 21Oakley: “Single Combat”, 1985, 392-410.

- 22Oakley: “Single Combat”, 1985.

- 23Martino: “Single Combat”, 2008.

- 24Oakley: “Single combat”, 1985, 410.

- 25Mann, Christian: “Um keinen Kranz, um das Leben kämpfen wir!” Gladiatoren im Osten des Römischen Reiches und die Frage der Romanisierung. Berlin 2011: Verlag Antike.

- 26Bentz, Martin / Mann, Christian: “Zur Heroisierung von Athleten”. In: von den Hoff, Ralf / Schmidt, Stefan (Eds.): Konstruktionen von Wirklichkeit. Bilder im Griechenland des 5. und 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Stuttgart 2001: Steiner, 225-240; François de Polignac: “Addendum to François de Polignac, ‘Athletes, statues and tyrants’. A few more thoughts on heroized athletes”. In: Thomas F. Scanlon (Ed.): Sport in the Greek and Roman worlds I. Early Greece, the Olympics, and contests. Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press, 112-116; see also Joseph Fontenrose: “The hero as athlete”. In: California Studies in Classical Antiquity, 1 (1968), 73-104.

- 27West: Indo-European Poetry, 2007, 486.

- 28Berwanger, Monika / Helmer, Matthias: “Zweikampf/Ringkampf”. In: Das Wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet, 2011. Online at: https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/stichwort/35598 (accessed on 18.06.2024).

- 29Maul, Stefan M.: Das Gilgamesch-Epos. Munich 2005: Beck; Sallaberger, Walther: Das Gilgamesch-Epos. Mythos, Werk und Tradition. Munich 2008: Beck.

- 30Latacz: Kampfparänese, 1977.

- 31Krischer, Tilman: Formale Konventionen der homerischen Epik. Munich 1971: Beck, 13-89.

- 32Latacz: Kampfparänese, 1977.

- 33Hellmann: Schlachtszenen, 2000.

- 34Esposito, Paolo: “Eroi e soldati. Osservazioni sulle battaglie in Virgillio e Lucano”. In: Vichiana 10 (1981), 62-90.

- 35See Martin, Richard P.: The Language of Heroes. Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca 1989: Cornell University Press.

- 36Dubischer, Markus: Die Agonszenen bei Euripides. Untersuchungen zu ausgewählten Dramen. Stuttgart 2001: Metzler.

- 37Froleyks, Walter J.: Der Agon Logon in der antiken Literatur. Diss. Bonn 1973, 360-381.

- 38Schoske, Sylvia: Das Erschlagen der Feinde. Ikonographie und Stilistik der Feindvernichtung im alten Ägypten. Munich 1982: Universität.

- 39Böhmer, Rainer Michael: Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit. Berlin 1965: de Gruyter; Ahlberg: Fighting, 71-85; Rohn, Karin: “Tierkampfszene”. In: Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 14. Boston 2014-2016: de Gruyter, 6-8.

- 40Keel, Othmar: “Die Deutung der Tierkampfzeichen auf den vorderasiatischen Rollsiegeln des 3. Jahrtausends”. In: Keel, Othmar (Ed.): Das Recht der Bilder, gesehen zu werden. Drei Fallstudien zur Methode der Interpretation altorientalischer Bilder. Fribourg 1992: Universitätsverlag; Steymans, Hans Ulrich: Gilgamesch. Ikonographie eines Helden. Fribourg 2010: Academic Press.

- 41Ahlberg: Fighting, 1971, 71-85; Ahlberg-Cornell, Gudrun: Myth and Epos in Early Greek Art. Stockholm 1971: Aström, 13-15; Vonhoff: Darstellungen von Kampf und Krieg, 2008. See for example the seals depicting scenes of humans engaged in single combat as well as lion combat from Grave Circle A at Mycenae: Arachne Bilddatenbank No. 157232 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/157232); 157230 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/157230); 157233 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/157233); 157237 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/157237) (accessed on 18.06.2024).

- 42Magen, Ursula: Assyrische Königsdarstellungen – Aspekte der Herrschaft. Eine Typologie. Mainz 1986: von Zabern.

- 43Ahlberg: Fighting 1971; Grunwald, Christiane: “Frühe attische Kampfdarstellungen”. In: Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica 15 (1983), 155-203.

- 44Hölscher, Tonio: Griechische Historienbilder des 5. und 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Würzburg 1973: Triltsch, 25-30; Recke: Gewalt und Leid, 2002, passim. – Herakles: Wünsche, Raimund / Brinkmann, Vinzenz (Eds.): Herakles – Herkules. Munich 2003: Staatliche Antikensammlungen. – Theseus: Neils, Jenifer: The youthful deeds of Theseus. Rome 1987: Bretschneider.

- 45Lorimer, Hilda L.: “The Hoplite Phalanx”. In: The Annual of the British School at Athens 42 (1947) 76-138; van Wees, Hans: “The Development of the Hoplite Phalanx. Iconography and Reality in the 7th Century”. In: van Wees, Hans (Ed.): War and Violence in Ancient Greece. London 2000: .

- 46Clairmont, Christoph W.: Classical Attical Tombstones. Kilchberg 1993: Akanthus, 143 Cat.No. 2209; Arachne Bilddatenbank No. 48532 (http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/48532) (accessed on 18.06.2024).

- 47Hölscher: Historienbilder, 1973: 25-30; Schäfer, Thomas. Andres Agathoi. Studien zum Realitätsgehalt der Bewaffnung attischer Krieger auf Denkmälern klassischer Zeit. Munich 1997: tuduv, 4-9; Ellinghaus: Aristokratische Leitbilder, 1997; see Lendon, Jon E.: Soldiers & Ghosts. A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity. New Haven 2005: Yale University Press.

- 48Muth: Gewalt im Bild, 2008.

- 49Knittlmayer: Attische Aristokratie, 1997, 68-69; Hölscher: “Images of War”, 2003, 8-12.

- 50Hölscher: Historienbilder 1973, 151-158; Cohen, Ada: The Alexander Mosaic. Stories of Victory and Defeat. Cambridge 1997: Cambridge University Press.

- 51Faust: Schlachtenbilder der römischen Kaiserzeit, 2012.

- 52See Wünsche, Raimund (Ed.): Lockender Lorbeer. Sport und Spiel in der Antike. Munich 2004: Staatliche Antikensammlungen.

- 53Knittlmayer: Attische Aristokratie, 1997, 69.

- 54Ahlberg: Fighting, 1971; Ahlberg-Cornell: “Myth and Epos”, 1992; Steymans: Gilgamesch, 2010.

- 55See Hellmann: Schlachtszenen, 2000.

- 56Hölscher: “Images of War”, 2003.

- 57Monestier, Martin: Duels. Les combats singuliers des origines à nos jours. Paris 1991: Sand.

5. Selected literature

- Ahlberg, Gudrun: Fighting on Land and Sea in Greek Geometric Art. Stockholm 1971: Åström.

- Berwanger, Monika / Helmer, Matthias: “Zweikampf/Ringkampf”. In: Das Wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet, 2011. Online at: https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/stichwort/35598 (accessed on 18.06.2024).

- Bie, Oscar: Kampfgruppen und Kämpfertypen in der Antike. Berlin 1891: Mayer & Müller. Online at: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bie1891 (accessed on 18.06.2024).

- Dubischer, Markus: Die Agonszenen bei Euripides. Untersuchungen zu ausgewählten Dramen. Stuttgart 2001: Metzler.

- Ellinghaus, Christian: Aristokratische Leitbilder – demokratische Leitbilder. Kampfdarstellungen auf athenischen Vasen in archaischer und frühklassischer Zeit. Münster 1997: Scriptorium.

- Esposito, Paolo: “Eroi e soldati. Osservazioni sulle battaglie in Virgillio e Lucano”. In: Vichiana 10 (1981), 62-90.

- Faust, Stefan: Schlachtenbilder der römischen Kaiserzeit. Erzählerische Darstellungskonzepte in der Reliefkunst von Traian bis Septimius Severus. Rahden 2012: Leidorf.

- Fenik, Bernard: Typical Battle Scenes in the Iliad. Studies in the Narrative Techniques of Homeric Battle Description. Wiesbaden 1968: Steiner.

- Fries, Jutta: Der Zweikampf: Historische und literarische Aspekte seiner Darstellung bei T. Livius. Königstein im Taunus 1985: Hain.

- Froleyks, Walter J.: Der Agon Logon in der antiken Literatur. Diss. Bonn 1973.

- Fortassier, Pierre: “A propos de l’emploi du duel chez Homère”. In: Revue des Etudes Grècques 102 (1989), 183-89.

- Grunwald, Christiane: “Frühe attische Kampfdarstellungen”. In: Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologice 15 (1983) 155-203.

- Hanson, Victor Davis: Hoplites. The Classical Greek Battle Experience. London 1993: Routledge.

- Hellmann, Oliver: Die Schlachtszenen der Ilias. Das Bild des Dichters vom Kampf in der Heroenzeit. Stuttgart 2000: Steiner.

- Hölscher, Tonio: “Images of War in Greece and Rome: Between Military Practice, Public Memory, and Cultural Symbolism”. In: The Journal of Roman Studies 93 (2003), 1-17.

- agan, Donald / Viggiano, Gregory F. (Eds.): Men of Bronze. Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece. Princeton 2013: Princeton University Press.

- Katz, Rebecca: “Combat, single”. In: Thomas, Richard F. (Ed.): The Virgil Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Chichester 2013: Wiley-Blackwell, 286-287.

- Keel, Othmar: “Die Deutung der Tierkampfzeichen auf den vorderasiatischen Rollsiegeln des 3. Jahrtausends”. In: Keel, Othmar (Ed.): Das Recht der Bilder, gesehen zu werden. Drei Fallstudien zur Methode der Interpretation altorientalischer Bilder. Fribourg 1992: Universitätsverlag.

- Latacz, Joachim: Kampfparänese, Kampfdarstellung und Kampfwirklichkeit in der Ilias, bei Kallinos und Tyrtaios. Munich 1977: Beck.

- Lendon, Jon E.: Soldiers & Ghosts. A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity. New Haven 2005: Yale University Press.

- Martin, Richard P.: The Language of Heroes. Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca 1989: Cornell University Press.

- Martino, John: “Single combat and the Aeneid”. In: Arethusa 41 (2008), 411-444; Katz, Rebecca: “Combat, single”. In: Thomas, Richard F. (Ed.): The Virgil Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Chichester 2013: Wiley-Blackwell, 286-287.

- Meier, Paul J.: “Das Schema der Zweikämpfe auf den älteren griechischen Vasenbildern”. In: Rheinisches Museum 37 (1882), 343-354.

- Mennenga, Ioanna: Untersuchung zur Komposition und Deutung homerischer Zweikampfszenen in der griechischen Vasenmalerei. Berlin 1976: Freie Universität.

- Mueller, Martin: “Duels”. In: Finkelberg, Margalit (Ed.): The Homer Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Oxford 2011: Wiley-Blackwell, 223-224.

- Muth, Susanne: Gewalt im Bild. Das Phänomen der medialen Gewalt im Athen des 6. und 5. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Berlin 2008: de Gruyter.

- Oakley, Stephen P.: “Single Combat in the Roman Republic”. In: Classical Quarterly 35 (1985), 392-410.

- Pirson, Felix: Ansichten des Krieges. Kampfreliefs klassischer und hellenistischer Zeit im Kulturvergleich. Wiesbaden 2014: Reichert.

- Recke, Matthias: Gewalt und Leid. Das Bild des Kriegers bei den Athenern im 6. und 5. Jh. v. Chr. Istanbul 2002: Yayinkari.

- Rohn, Karin: “Tierkampfszene”. In: Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 14. Boston 2014-2016: de Gruyter, 6-8.

- Rollinger, Robert: “Sport und Spiel”. In: Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 13. Boston: de Gruyter 2011, 6-16.

- Sabin, Philip (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare. Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Scanlon, Thomas Francis: Sport in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press.

- Schwartz, Adam: Reinstating the Hoplite. Arms, Armour, and Phalanx Fighting in Archaic and Classical Greece. Stuttgart 2013: Steiner.

- Steymans, Hans Ulrich: Gilgamesch. Ikonographie eines Helden. Fribourg 2010: Academic Press.

- Stoevesandt, Magdalene: Feinde – Gegner – Opfer. Zur Darstellung der Troianer in den Kampfszenen der Ilias. Basel 2004: Schwabe.

- Udwin, Victor M.: Between Two Armies. The Place of the Duel in Epic Culture. Leiden 1999: Brill.

- van Wees, Hans: Status Warriors. War, Violence, and Society in Homer and History. Amsterdam 1992: Gieben.

- van Wees, Hans: “The Homeric Way of War. The ‘liad’ and the Hoplite Phalanx”. In: Greece & Rome 41 (1994) 1-18; 131-155.

- van Wees, Hans: “The Development of the Hoplite Phalanx. Iconography and Reality in the 7th Century”. In: van Wees, Hans (Ed.): War and Violence in Ancient Greece. London 2000: Duckworth.

- Vonhoff, Christian: Darstellungen von Kampf und Krieg in der minoischen und mykenischen Kultur. Rahden 2008: Leidorf.

- West, Martin L.: Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford 2007: Oxford University Press.

6. List of images

- 1Fight against a mythical monster (Gilgamesh and Enkidu against Humbaba?), stone relief from northern Syria, 10th century BC, basalt, hight: 63 cm, Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum, Inv.-No. 21.18.Source: The Walters Art MuseumLicence: Creative Commons Zero

- 2Single combat, seal found in Grave III of Grave Circle A (Mycenae), 16th century BC, gold, 1.8 cm x 1.2 cm, Athens, National Archaeological Museum.Licence: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

- 3Depiction of lion combat on a pottery tripod, ca. 740 BC, pottery, hight: 17.8 cm, Athens Kerameikos Museum, Inv.-No. 497.Licence: Attribution only

- 4Heracles fighting the Nemean lion / head of Athena, silver stater from Heracleia in Lucania, ca. 400 v. Chr., silver, diameter: 2.1 cm.Source: Franke, Peter R. / Hirmer, Max: Die griechische Münze. Munich 1964: Hirmer. Nr. 257.Licence: All rights reserved, quotation (German Act on Copyright and Related Rights, Section 51 / § 51 UrhG)

- 5Hoplite fighters with Athena and Hermes, Attic red-figure amphora, ca. 520 BC, pottery, hight: 57.2 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, Inv.-No. G 1.Source: User:Jastrow / Wikimedia CommonsLicence: Public domain

- 6Grave relief of the cavalryman Dexileos, Dipylon cemetery (Kerameikos), 394/3 BC, pentelic marble, hight: 2.21 m, Athens, Kerameikos Museum, Inv.-No. P 1130.Licence: Attribution only

- 7Mosaic depicting the battle of Alexander the Great against the Persian king Darius III from the Casa del Fauno in Pompeii, 2nd century BC copy of a Hellenistic Greek painting made during the late 4th / early 3rd century BC, mosaic/stone, 5.13 m x 2.72 m, Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Inv. No. 10020.Licence: Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0

- 8Relief depicting Hadrian hunting a boar, ca. 135 AD, mable, diameter: 2.20 m, Rome, on the Arch of Constantine.Source: User:Sailko / it.wikipedia.orgLicence: Public domain

- 9Pankration (wrestling) with adjudicator, Attic black-figured amphora awarded as a prize to the winner of the Panathenaic Games, 332/1 BC, pottery, hight: 77 cm, London, The British Museum Inv.-No. 1873,0820.370.Source: Trustees of the British MuseumLicence: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0