- Version 1.0

- published 27 September 2022

Table of content

1. Introduction

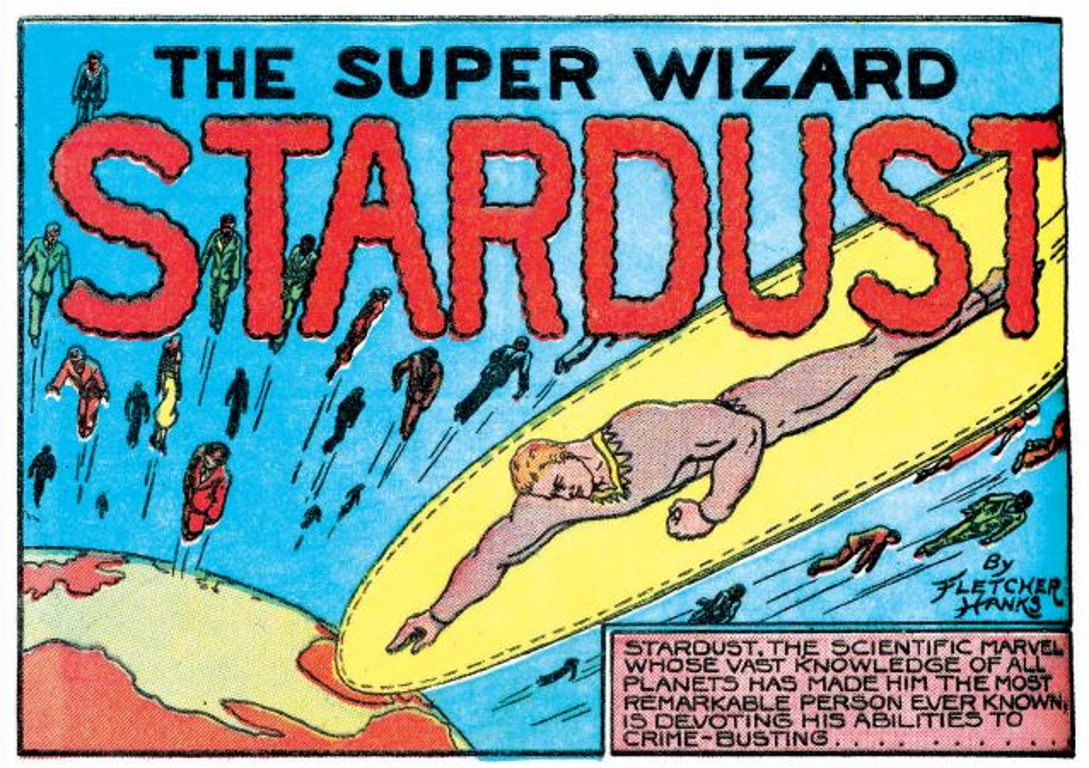

What is a superhero? If we look at an example from the time when superheroes were created, we can note some basic characteristics of the superheroic. For example, Stardust (cf. fig. 1) is a costumed hero who can fly. One block of text further adds that he is a scientific wonder and that he possesses extensive knowledge, making him the most remarkable person of all time. Moreover, Stardust uses his abilities to fight crime.

Superheroes and superheroines are defined by the fight against crime, which is as personal as it is physical. In most cases, they fight against the disruption of the symbolic order in a uniquely individual and often colourful costume that marks them as superheroes or superheroines. In many cases, they possess unique, hence superhuman and miraculous superpowers, or at least the will and ability to defeat villains, supervillains and their criminal organisations outside of institutional powers such as the police or the military, either tolerated or as vigilantes. Of further importance is the origin story of the heroines and heroes, in which it is told and shown how and why the superhero becomes a superhero. The figure of the superhero originated in the American comic books of the late 1930s, but quickly spread through most media such as radio, film, television or computer games.

The decisive feature of superheroism is its fictionality: superheroes fall outside the worldly realms of heroism by virtue of their fantastic character.1Cf. Stahl, Karl-Heinz: Das Wunderbare als Problem und Gegenstand der deutschen Poetik des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt am Main 1975: Athenaion. While the heroic may in most cases be epistemically a cultural attribution rather than a specific characteristic of historical persons, this does not apply to superheroism. Superheroes are, in a tautological way, figures who define themselves by their superheroism. This means that they are fictional figures who, in Carl Schmitt’s view, not only rule sovereignly over the state of exception, but create it themselves as fantastic exceptional figures, consequently as superhumans.2Cf. Schmitt, Carl: Politische Theologie. Vier Kapitel zur Lehre von der Souveränität. Berlin 1996 (1922): Duncker & Humblot.

The use of their usually miraculous abilities, namely: their superpowers, which distinguish them from other people and remove them from the grids of normalisation schemes3Cf. Link, Jürgen: Versuch über den Normalismus. Wie Normalität produziert wird. Göttingen 2006: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht., is therefore also staged in most cases as a visual exception – be it in comics, films, TV series or computer and video games. The graphic element is therefore an essential part of the superhero narrative. In terms of motifs, the demonstration of superpowers usually takes the form of a violent confrontation between the superhero and one or more criminals, sometimes a supervillain with equally supernatural powers, or a criminal organisation. Sometimes it is also a matter of saving people or objects from death and destruction, as in the case of the first superhero Superman, who has been saving crashing airplanes on and off since 1938.

2. Forms of representation

There is much to be said for considering superhero stories as a genre of their own.4Cf. Coogan, Peter: Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre. Austin, TX 2006: Monkeybrain. One could speak of a modern genre or a second-order genre, because the superhero story is built on several longer-standing genres. In most cases, it follows a crime plot that has been reduced to an adventure and action format since the beginning of entertainment and pulp literature. This means that at the outset a crime disrupts the symbolic order, which must then be restored by the superhero. Usually this happens without much investigation via the pursuit and fighting of the criminals. At its core, the superhero narrative can be described as a genre of fantastic action whose aim is to showcase the miraculous in a spectacular way. In terms of fantasy theory, the origin of the marvelous is maximally de-differentiated: The source of the miraculous in the superhero story, i.e. the origin of the superpowers, can come from a science fiction context, for example through futuristic technical developments or through an accident with cosmic or radioactive rays. However, it can also come from a mythology or fantasy context, a non-rationalised magical source or a divine origin. One could say that the radically syncretic superhero genre is more concerned with the visual staging of the miraculous and thus the sublime and less with its diegetic condition of possibility.

In most cases, the fantastical action of the superhero narrative is countered by a narrative style committed to realism, both graphically and narratively. The stories are told in a linear fashion and are easy to follow. Of high relevance for these stories is in most cases also a contemporary and conspicuously often an urban setting – with a city in the background that either depicts an extra-literary city or represents an extrapolation or hybridisation.5See Ahrens, Jörn / Meteling, Arno (Eds.): Comics and the City: Urban Space in Print, Picture and Sequence. New York/London 2010: Continuum. Popular example for the first case is New York in the superhero universe of Marvel comics as seen in comics, films or TV series. The fictional cities of the DC Comics universe are paradigmatic for the second method: thus Metropolis, the city where Superman is at home, and Gotham, where Batman operates, can usually be read as two different interpretations of real New York. One could therefore say that a realistic and recognisable setting provides the necessary complementary background for the exceptional figure of the superheroine or superhero. In summary, the emergence of the exceptional figures initiates and exposes exceptional scenes, which visually and narratively break out of the realistic narrative flow of the plot.

These exceptional aspects find their body-political counterpart in the superhero’s diegetic sovereignty over the world in which he lives, over his fellow human beings as well as over law and order. Superheroes usually have double identities and wear masks and costumes. As masked vigilantes with secret identities, they can elude the grasp of the state and are only manifest in their – in the Kantian sense – public form, i.e. when they appear in their activity in costume and mask and thus ultimately embody a specific representative regime of self-determined rule themselves.6Rancière, Jacques: Die Aufteilung des Sinnlichen. Die Politik der Kunst und ihre Paradoxien. Berlin 2006: b_books. However, the superhero in mask and costume, as superhuman as he is public, is not solely above the law, but is also immortal in two ways: In most versions, superhero death is reversible, and the chance that the superheroine or superhero comes back to life for some reason increases with the popularity of the character. With Superman’s death fighting Doomsday in 1992 or Captain America’s in 2007, one could expect both heroes to be resurrected after a period of time. Even superheroes who have been dead for decades are not immune to returning – such as Jason Todd, as second Robin, Batman’s sidekick, or James Buchanan “Bucky” Barnes, Captain America’s equally youthful sidekick during World War II. The second – and for the first reason usually only temporary – version is the dynastic solution, namely that the private person under the mask dies while someone else continues the tradition of the masked superhero.

From an aesthetic and choreographic perspective, the exceptional bodies and exceptional actions of the superhero narrative can be defined as a tense combination of elements of the beautiful, the sublime and the grotesque. The bodies of most superheroes fall into the register of a classicist ideal of beauty through their “noble simplicity and […] quiet grandeur” (“edle Einfalt und […] stille Größe”).7Winckelmann, Johann Joachim: Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst (1755). In: Werke in einem Band. Berlin 1969: Aufbau-Verlag, 17-18. Their perfect bodies and imposing postures (for example, the three-point or superhero landing) are often in the visual tradition of ancient statues of heroes and gods, to which Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing referred as a classicist ideal of beauty. Central to the genre, however, is at the same time the sublime nature of the superhero’s body and his actions, which lie beyond all beauty, for they are sometimes beyond all human standards. Typical of this are the superhuman physical superiority, represented by a hyper muscular physique, and the ability to fly. Two perspectives support the sublime aspect of the representation: the Olympic or panoptic view of the superhero or superheroine from above and, correspondingly, the view of the people – who usually have to be protected and guarded – from below, up to the heroes and heroines flying over them or ascending. The moment of the hero’s or heroine’s sublimity is reinforced if they have wings or their secular counterpart, a cape. However, many superheroes and superheroines also exhibit an aesthetic of the grotesque. Winged superheroes, for example, certainly correspond to an aesthetic of the beautiful and sublime, but as hybrid beings between humans and animals, they fall precisely under the aesthetic compositional principle of grotesque hybridity.8Bachtin, Michail: Rabelais und seine Welt. Volkskultur als Gegenkultur. Ed. by Renate Lachmann. Frankfurt am Main 1995: Suhrkamp. This is about body drama, which is characterised by procedures of inversion, degradation and profanation, by masking, accumulation of figures and above all by hybridisation, such as human-animal and human-thing connections, as well as by metamorphoses. Sometimes there is also a monstrous hypertrophy of the muscular body – one thinks of the Hulk or the Thing of the Fantastic Four of Marvel Comics. Above all, however, there are numerous human-animal hybrids among superheroes, such as Batman as a human-bat hybrid (even if only as a disguise) or Spider-Man, Black Panther, The Human Wasp, Ant-Man, Wolverine or Nightcrawler.

3. History

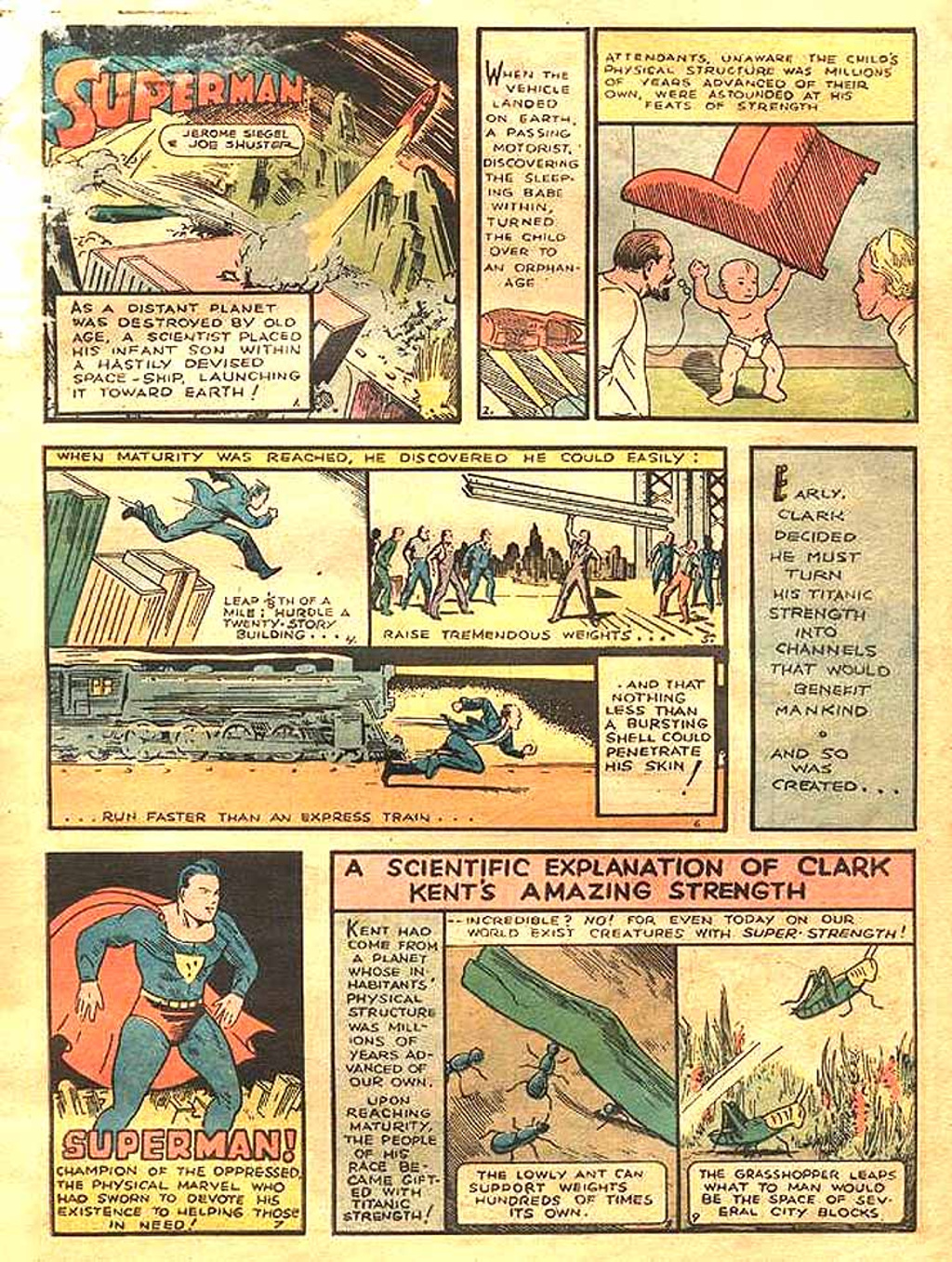

The origin of superheroes can be pinpointed precisely with the appearance of Superman in Action Comics 1 (1938). The superhero with superhuman abilities, a costume and a secret second identity can be understood as the most independent genre of comics. Already in Action Comics 1, these features of the superhero story are present in addition to the likes of a clear mission and the origin narrative (fig. 2). The entire genre of superheroes has its nucleus in this short narrative about Superman.9Cf. Coogan: Superhero, 2006, 192.

The heroic models of superheroes can be found, firstly, in entertainment literature: in the voluminous serial novels of the 19th century, such as Alexandre Dumas’ Le Comte de Monte-Cristo (The Count of Monte Cristo) (1844–1846), as well as in the pulp magazines and radio serials of the early 20th century, in which masked vigilante heroes like Zorro (1919) or The Shadow (1930) fight against master criminals and their organisations. Secondly, templates of superheroism can be discerned in both myth and epic stories. Jess Nevins, for example, recognises the first proto-superhero in Gilgamesh’s sidekick Enkidu.10Nevins, Jess: The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger: the 4.000-year History of the Superhero. Santa Barbara, California 2017: ABC-CLIO.

Above all, however, there are lines of tradition that emanate from Greco-Roman and Nordic-Germanic mythology as well as the heroic epics of antiquity and the Middle Ages. There are direct adoptions – such as the thunder god Thor or the Greek demigod Hercules in the Marvel Comics universe or Wonder Woman, the Amazon and daughter of Zeus in the DC Comics universe – or also popular cultural reinterpretations of the mythical pantheons such as the ‘speedsters’ Flash or Quicksilver, who refer to Hermes and Mercury respectively, or Superman and epigones such as his Image Comics counterpart Apollo (sic!), whose powers can be interpreted as those of sun gods. The DC Comics superhero Green Lantern, for example, is a version of Aladdin and the magic lamp from the Arabian Nights.11Cf. Morrison, Grant: Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human. New York 2012: Spiegel & Grau. Superheroes could be understood as continuous embodiments of the mythical, as generally defined by Manfred Frank: “One counts myth among the non-descriptive, namely among the symbolic forms of expression.”12Frank, Manfred: “Die Dichtung als ‘Neue Mythologie’”. In: Bohrer, Karl Heinz (Ed.): Mythos und Moderne. Begriff und Bild einer Rekonstruktion. Frankfurt am Main 1983: Suhrkamp, 15-40, 17-18. They do not reflect the world but the imaginary of it in myth and literature and are thus elements of a New Mythology in the sense of Romanticism. They present a modern and self-reflexively poetic, hence logically framed version of myth. Although superhero narratives repeatedly spell out their respective theogonies and thus refer to the significance of their very own world building, it is no longer about myth as an explanation of the world, but about a self-conscious poeticity.

With regard to the evolution of superheroes and superheroines, several eras are usually distinguished. The most common is the distinction between a Golden Age, Silver Age and Bronze Age.13Ecke, Jochen: “Superheldencomics”. In: Abel, Julia / Klein, Christian (Eds.): Comics und Graphic Novels. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart 2015: Metzler, 233-247, 234. Coogan elaborates on this and identifies the following periods14Coogan: Superhero, 2006, 193-194.: Golden Age (1938 to 1956 with Plastic Man 64), Silver Age (1956 Showcase 4 to 1971 Teen Titans 31), Bronze Age (1971 Superman 233 to 1980 Legion of Super-Heroes 259), Iron Age (1980 DC Comics Presents 26 to 1987 Justice League of America 261 and 2000 Heroes Reborn/Heroes Return respectively) as well as Renaissance Age (1987 Justice League 1 and 2000 The Sentry respectively). The classification criteria are based on the increasing complexity of both the character psychology and the plot structures. Ecke criticises, not entirely without justification15Ecke: “Superheldencomics”, 2015, 234-235., that this implies a seemingly teleological development. However, the ages of superheroes can also be compared to changes in the readership: While in the beginning this was children and adolescents, since the 1970s a shift towards adults can be observed. After 2000 at the latest, adults represent the majority of the readers of superhero comics.16Cf. Wright, Bradford W.: Comic Book Nation. The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore 2003: Johns Hopkins University Press, 226ff.; Riesman, Abraham: Forget Brooding Superheroes – the Big Money Is in Kid’s Comics (2017). Online at: http://www.vulture.com/2017/06/raina-telgemeier-kids-comics.html (accessed on 08.08.2018). The changes in the complexity of superhero comics must therefore also be seen, at least in part, as a reaction of the publishers to changing economic conditions.

Some self-contained superhero narratives from the 1980s represent an important developmental step here. Alongside Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight (1986), this is especially the case with Dave Gibbons’ and Alan Moore’s Watchmen (1986–1987). Both series unmask superheroes as broken personalities who take the law into their own hands without authorisation and are sometimes staged as self-righteous thugs. Such legal and moral realignments go hand in hand with a dramatic portrayal of ⟶violence, which previously only appeared as an exaggeration in superhero comics. Currently, superhero comics continue to be characterised by an exploration of the human in the superheroic. However, for the first time in a while, a plurality can be seen on both the plot and production levels. Social aspects such as diversity, race and gender are increasingly being addressed, which can be seen in the coming out of individual characters (for example Batwoman, Northstar, Golden Age Green Lantern, Apollo and Midnighter in The Authority), a multitude or strengthening of female superheroes (Ms. Marvel, Spider-Gwen) or the reinterpretation of established characters as people of color (Nick Fury, Ultimate Spider-Man) or as women (Captain Marvel, Thor).

4. Seriality and mediality

Undoubtedly, superheroes are visible in various media – in film, on television, and in computer or video games, less so on radio or in prose. More recently, there has been a trend toward transmedia storytelling. However, the superhero has its origins – with the aforementioned precursors – in comics. This provenance has led to certain narrative aspects becoming intrinsic to the superhero story: The first to be mentioned here is seriality, i.e. the coherence of the narrative across several sequels, recognisable through similarity. Thus, in most cases, a superhero comic series is characterised by a periodic mode of publication and correspondingly by the recurrence of characters, setting, themes, and sometimes even certain narrative styles.17Meteling, Arno: “To Be Continued … – Zum seriellen Erzählen im Superhelden-Comic”. In: Brunken, Otto / Giesa, Felix (Eds.): Erzählen im Comic. Beiträge zur Comicforschung. Bochum 2013: Bachmann, 89-112. The economic logic of repetition and continuation is characterised in superhero stories by the recurring appearance of the heroines and heroes, the villains, as well as by a constant setting and sometimes similar storylines. For a long time, the superhero story, especially in comics, corresponded to the form of the ‘series’ or ‘procedural’.18Cf. Oltean, Tudor: “Series and Seriality in Media Culture”. In: European Journal of Communication 8 (1993), 5-31; Meteling, Arno / Otto, Isabell / Schabacher, Gabriele (Eds.): „Previously on …“ – Zur Ästhetik der Zeitlichkeit neuerer TV-Serien. München 2010: Fink. This means that the framework conditions of the series, such as the constellation of characters, remain largely stable, but there is a new case to solve in each new issue. The recognisability of characters, setting and plot is an important criterion for reader and viewer loyalty to a series. No major effects of verfremdung or innovations are allowed, and the series must always follow certain patterns and traditions, graphically and narratively. However, there must be no repetition of certain aspects at short intervals, so as not to bore readers.19Cf. Eco, Umberto: “Der Mythos von Superman”. In: Eco, Umberto: Apokalyptiker und Integrierte. Zur kritischen Kritik der Massenkultur. Frankfurt am Main 1994: Fischer, 187-222. Furthermore, elements of the ‘serial’ have become increasingly established – a format that changes continuously, is potentially infinite, and therefore knows above all figures of postponement and retardation. Of importance for the serial are, for example, the psychologisation and further development of the characters, the insertion of subplots, and the linking of ever-new relationships between the characters. Paradigmatic for the serial is the soap opera, whose melodramatic elements become important with the Marvel Comics superheroes in the 1960s.

Over the decades, a confusing archive of detailed information has developed for each superhero universe, such as the DC universe since the 1930s, the Marvel universe since the 1960s, or the Wildstorm universe since the 1990s. These universes not only each form their own and constantly growing library, but they are also accompanied by a form of reader education. In the best case, the reader should still understand or at least be interested in allusions to earlier events and characters decades later. The superhero story thus follows the primacy of pop culture and fan discourse to shape and hierarchise elites through positivist detailed knowledge. Complicating knowledge of the superhero universe is the growing multiplication of superhero interpretations in the media. Not only do these historically experience repeated updates20Cf. Meteling, Arno: “Batman. Pop-Ikone und Mediensuperheld”. In: Kiefer, Bernd / Stiglegger, Marcus (Eds.): Pop & Kino. Mainz 2004: Bender, 161-174., but also sometimes contradictory delineations and thus receptions in the various modes and media.21Cf. Frahm, Ole: “Wer ist Superman? Mythos und Materialität einer populären Figur”. In: Diekmann, Stefanie / Schneider, Matthias (Eds.): Szenarien des Comic. Helden und Historien im Medium der Schriftbildlichkeit. Berlin 2005: SuKuLTuR, 35-49.

5. Research overview

In its first few decades, early research on superheroes has largely focused on their appearances in comic books. More media-focused research can only be discerned with the success of superhero movies, television series, and computer games after the turn of the millennium.22Cf. Friedrich, Andreas / Rauscher, Andreas (Eds.): Superhelden zwischen Comic und Film. Film-Konzepte 6. München 2007: edition text + kritik. Superheroes first came under scrutiny primarily in the critique of ideology during the 1960s and 1970s23Cf. Drechsel, Wiltrud Ulrike / Funhoff, Jörg / Hoffmann, Michael: Massenzeichenware. Die gesellschaftliche und ideologische Funktion der Comics. Frankfurt am Main 1975: Suhrkamp., including in the powerful essay The Myth of Superman (1964). In this essay, Umberto Eco sees Superman as a mass-literary ideological model, which, due to the double identity of the character, offers the reader the possibility of projection.24Cf. Eco: “Der Mythos von Superman”, 1978, 187-222. Almost thirty years later, Reinhard Schweizer’s approach is highly significant, as he examines ‘ideology and propaganda in the Marvel superhero comics’ (1992, german: Ideologie und Propaganda in den Marvel-Superheldencomics), for example, how anti-communist positions are represented in the comic series Captain America, while the Vietnam War is also critically questioned in the same series.25Schweizer, Reinhard: Ideologie und Propaganda in den Marvel-Superheldencomics. Vom Kalten Krieg zur Entspannungspolitik. Frankfurt am Main u.a. 1992: Peter Lang.

Since the turn of the millennium, there have been numerous publications dealing with the formal and narrative structure of superhero comics.26Cf. Ditschke, Stephan / Anhut, Anjin: “Menschliches, Übermenschliches. Zur narrativen Struktur von Superheldencomics”. In: Ditschke, Stephan / Kroucheva, Katerina / Stein, Daniel (Eds.): Comics. Zur Theorie und Geschichte eines populärkulturellen Mediums. Bielefeld 2009: Transcript, 131-178. They focus on specifics of the genre, such as the splash page that opens the story27Cf. Meteling, Arno: “Splash Pages – Zum graphischen Erzählen im Superhelden-Comic”. In: Packard, Stephan (Ed.): Medienobservationen. Bilder des Comics. Beiträge zur 5. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Comicforschung 2010. 2012. Online at: http://www.medienobservationen.lmu.de/artikel/comics/comics_pdf/meteling_comfor.pdf (accessed on 27.05.2018)., the basics of serial storytelling28Kelleter, Frank / Stein, Daniel: “Autorisierungspraktiken seriellen Erzählens. Zur Gattungsentwicklung von Superheldencomics”. In: Kelleter, Frank (Ed.): Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld 2012: transcript, 259-290., or characterisation29Kukkonen, Karin: Neue Perspektiven auf die Superhelden. Polyphonie in Alan Moores “Watchmen”. Marburg 2008: Tectum.. These studies essentially adapt approaches from cultural and literary studies as well as narratology to the genre of superhero comics. In addition to numerous accounts of individual heroines and heroes, especially Batman30See Brooker, Will: Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon. New York/London 2001: Continuum; Pearson, Roberta E. / Uricchio, William (Eds.): The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. New York/London 1991: Routledge. Pearson, Robert / Uricchio, William / Brooker, Will (Eds.): Many More Lives of the Batman. London 2015: British Film Institute; Weldon, Glen: The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture. New York 2016: Simon & Schuster., more recent research has increasingly addressed aspects of diversity, race, class, and gender, sometimes at the risk of committing a biographical fallacy. For example, in relation to the Jewish ancestry of the creators of Superman, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the Jewish history of superheroes is discussed. This history is not limited to ancestry, however, but is also said to be evident in religious as well as mythological influences, as well as a Jewish identity, as accounted for by Clark Kent, Superman’s secret identity. Superman can thus be read as a redeemer figure of an oppressed group of people.31Meinrenken, Jens: “Eine jüdische Geschichte der Superheldencomics”. In: Kampmayer-Käding, Margret / Kugelmann, Cilly (Eds.): Helden, Freaks und Superrabbis. Die jüdische Farbe des Comics. Berlin 2010: Stiftung Jüdisches Museum Berlin, 26-41. On the other hand, in the study of superheroes of colour, it is repeatedly made clear that they also represent a marginalised group in superhero narratives.32Brown, Jeffrey: Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics and their Fans. Jackson 2000: University Press of Mississippi.

Gender theory approaches to superheroes have opened up the superhero body as a discursive space. On the one hand, the significance of the heroic for a society is addressed33. Arnaudo, Marco: The Myth of the Superhero. Baltimore 2013: Johns Hopkins University Press., and on the other hand, questions of femininity or female roles are negotiated in the body images of female superheroes in particular. While the bodies of male superheroes, in contrast, are criticised as being part of the heteronormative hegemony, a breaking down of such norms is observed in homosexual superheroes.34Banhold, Lars: Pink Kryptonite. Das Coming-out der Superhelden. Bochum 2012: Bachmann. Finally, Scott Jeffrey reads the superhero body as post-human and thus as a resonating space for military, state, and corporate power.35Jeffrey, Scott: The Posthuman Body in Superhero Comics. Human, Superhuman, Transhuman, Post/Human. New York u. a. 2016: Palgrave Macmillan. He notes that superheroes, as beings on a permanent hero’s journey, could be an aid to the question of what one wants to become, not what one is – especially as the coexistence of aliens, robots, cyborgs, mutants, and humans is presented as an ethical constant in superhero teams.

6. References

- 1Cf. Stahl, Karl-Heinz: Das Wunderbare als Problem und Gegenstand der deutschen Poetik des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt am Main 1975: Athenaion.

- 2Cf. Schmitt, Carl: Politische Theologie. Vier Kapitel zur Lehre von der Souveränität. Berlin 1996 (1922): Duncker & Humblot.

- 3Cf. Link, Jürgen: Versuch über den Normalismus. Wie Normalität produziert wird. Göttingen 2006: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- 4Cf. Coogan, Peter: Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre. Austin, TX 2006: Monkeybrain.

- 5See Ahrens, Jörn / Meteling, Arno (Eds.): Comics and the City: Urban Space in Print, Picture and Sequence. New York/London 2010: Continuum.

- 6Rancière, Jacques: Die Aufteilung des Sinnlichen. Die Politik der Kunst und ihre Paradoxien. Berlin 2006: b_books.

- 7Winckelmann, Johann Joachim: Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst (1755). In: Werke in einem Band. Berlin 1969: Aufbau-Verlag, 17-18.

- 8Bachtin, Michail: Rabelais und seine Welt. Volkskultur als Gegenkultur. Ed. by Renate Lachmann. Frankfurt am Main 1995: Suhrkamp.

- 9Cf. Coogan: Superhero, 2006, 192.

- 10Nevins, Jess: The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger: the 4.000-year History of the Superhero. Santa Barbara, California 2017: ABC-CLIO.

- 11Cf. Morrison, Grant: Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human. New York 2012: Spiegel & Grau.

- 12Frank, Manfred: “Die Dichtung als ‘Neue Mythologie’”. In: Bohrer, Karl Heinz (Ed.): Mythos und Moderne. Begriff und Bild einer Rekonstruktion. Frankfurt am Main 1983: Suhrkamp, 15-40, 17-18.

- 13Ecke, Jochen: “Superheldencomics”. In: Abel, Julia / Klein, Christian (Eds.): Comics und Graphic Novels. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart 2015: Metzler, 233-247, 234.

- 14Coogan: Superhero, 2006, 193-194.

- 15Ecke: “Superheldencomics”, 2015, 234-235.

- 16Cf. Wright, Bradford W.: Comic Book Nation. The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore 2003: Johns Hopkins University Press, 226ff.; Riesman, Abraham: Forget Brooding Superheroes – the Big Money Is in Kid’s Comics (2017). Online at: http://www.vulture.com/2017/06/raina-telgemeier-kids-comics.html (accessed on 08.08.2018).

- 17Meteling, Arno: “To Be Continued … – Zum seriellen Erzählen im Superhelden-Comic”. In: Brunken, Otto / Giesa, Felix (Eds.): Erzählen im Comic. Beiträge zur Comicforschung. Bochum 2013: Bachmann, 89-112.

- 18Cf. Oltean, Tudor: “Series and Seriality in Media Culture”. In: European Journal of Communication 8 (1993), 5-31; Meteling, Arno / Otto, Isabell / Schabacher, Gabriele (Eds.): „Previously on …“ – Zur Ästhetik der Zeitlichkeit neuerer TV-Serien. München 2010: Fink.

- 19Cf. Eco, Umberto: “Der Mythos von Superman”. In: Eco, Umberto: Apokalyptiker und Integrierte. Zur kritischen Kritik der Massenkultur. Frankfurt am Main 1994: Fischer, 187-222.

- 20Cf. Meteling, Arno: “Batman. Pop-Ikone und Mediensuperheld”. In: Kiefer, Bernd / Stiglegger, Marcus (Eds.): Pop & Kino. Mainz 2004: Bender, 161-174.

- 21Cf. Frahm, Ole: “Wer ist Superman? Mythos und Materialität einer populären Figur”. In: Diekmann, Stefanie / Schneider, Matthias (Eds.): Szenarien des Comic. Helden und Historien im Medium der Schriftbildlichkeit. Berlin 2005: SuKuLTuR, 35-49.

- 22Cf. Friedrich, Andreas / Rauscher, Andreas (Eds.): Superhelden zwischen Comic und Film. Film-Konzepte 6. München 2007: edition text + kritik.

- 23Cf. Drechsel, Wiltrud Ulrike / Funhoff, Jörg / Hoffmann, Michael: Massenzeichenware. Die gesellschaftliche und ideologische Funktion der Comics. Frankfurt am Main 1975: Suhrkamp.

- 24Cf. Eco: “Der Mythos von Superman”, 1978, 187-222.

- 25Schweizer, Reinhard: Ideologie und Propaganda in den Marvel-Superheldencomics. Vom Kalten Krieg zur Entspannungspolitik. Frankfurt am Main u.a. 1992: Peter Lang.

- 26Cf. Ditschke, Stephan / Anhut, Anjin: “Menschliches, Übermenschliches. Zur narrativen Struktur von Superheldencomics”. In: Ditschke, Stephan / Kroucheva, Katerina / Stein, Daniel (Eds.): Comics. Zur Theorie und Geschichte eines populärkulturellen Mediums. Bielefeld 2009: Transcript, 131-178.

- 27Cf. Meteling, Arno: “Splash Pages – Zum graphischen Erzählen im Superhelden-Comic”. In: Packard, Stephan (Ed.): Medienobservationen. Bilder des Comics. Beiträge zur 5. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Comicforschung 2010. 2012. Online at: http://www.medienobservationen.lmu.de/artikel/comics/comics_pdf/meteling_comfor.pdf (accessed on 27.05.2018).

- 28Kelleter, Frank / Stein, Daniel: “Autorisierungspraktiken seriellen Erzählens. Zur Gattungsentwicklung von Superheldencomics”. In: Kelleter, Frank (Ed.): Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld 2012: transcript, 259-290.

- 29Kukkonen, Karin: Neue Perspektiven auf die Superhelden. Polyphonie in Alan Moores “Watchmen”. Marburg 2008: Tectum.

- 30See Brooker, Will: Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon. New York/London 2001: Continuum; Pearson, Roberta E. / Uricchio, William (Eds.): The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. New York/London 1991: Routledge. Pearson, Robert / Uricchio, William / Brooker, Will (Eds.): Many More Lives of the Batman. London 2015: British Film Institute; Weldon, Glen: The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture. New York 2016: Simon & Schuster.

- 31Meinrenken, Jens: “Eine jüdische Geschichte der Superheldencomics”. In: Kampmayer-Käding, Margret / Kugelmann, Cilly (Eds.): Helden, Freaks und Superrabbis. Die jüdische Farbe des Comics. Berlin 2010: Stiftung Jüdisches Museum Berlin, 26-41.

- 32Brown, Jeffrey: Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics and their Fans. Jackson 2000: University Press of Mississippi.

- 33. Arnaudo, Marco: The Myth of the Superhero. Baltimore 2013: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- 34Banhold, Lars: Pink Kryptonite. Das Coming-out der Superhelden. Bochum 2012: Bachmann.

- 35Jeffrey, Scott: The Posthuman Body in Superhero Comics. Human, Superhuman, Transhuman, Post/Human. New York u. a. 2016: Palgrave Macmillan.

7. Selected literature

- Ahrens, Jörn / Meteling, Arno (Eds.): Comics and the City. Urban Space in Print, Picture and Sequence. New York/London 2010: Continuum.

- Arnaudo, Marco: The Myth of the Superhero. Baltimore, MD 2013: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bahlmann, Andrew R.: The Mythology of the Superhero. Jefferson, NC 2016: McFarland.

- Beaty, Bart / Weiner, Stephen (Eds.): Heroes & Superheroes. Vol. 2. Englewood Cliffs 2012: Salem Press.

- Coogan, Peter: Superhero. The Secret Origin of a Genre. Austin, TX 2006: Monkeybrain.

- Dath, Dietmar: Superhelden. 100 Seiten. Stuttgart 2016: Reclam.

- Drechsel, Wiltrud Ulrike / Funhoff, Jörg / Hoffmann, Michael: Massenzeichenware. Die gesellschaftliche und ideologische Funktion der Comics. Frankfurt a. M. 1975: Suhrkamp.

- Eco, Umberto: “The Myth of Superman”. In: Eco, Umberto: Apokalyptiker und Integrierte. Zur kritischen Kritik der Massenkultur. Frankfurt a. M. 1994: Fischer, 187-222.

- Engelns, Markus: “Aquaman sucks!” – Spezialwissen und die neue Popularität der Superhelden. Essen 2014: Bachmann.

- Hatfield, Charles / Heer, Jeet / Worcester, Kent (Eds.): The Superhero Reader. Jackson, MS 2013: University Press of Mississippi.

- Jones, Gerard / Jacobs, Will: The Comic Book Heroes. The First History of Modern Comic Books from the Silver Age to the Present. Rocklin, CA 1997: Prima Lifestyles.

- Jones, Gerard: Men of Tomorrow. Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book. London 2005: Basic Books.

- Klock, Geoff: How to Read Superhero Comics and Why. New York/London 2002: Bloomsbury.

- Morrison, Grant: Supergods. What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human. New York 2011: Spiegel & Grau.

- Ndalianis, Angela (Ed.): The Contemporary Comic Book Superhero. New York/London 2006: Routledge.

8. List of images

- The Super Wizard Stardust, from Fletcher Hanks: “The Super Wizard Stardust: Gyp Clip’s Anti-Gravity Ray”. In: Fantastic Comics #7, 1940.Source: The Comics of Fletcher Hanks. I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets! Ed. by Paul Karasik. Seattle 2008: Fantagraphics, 42.Licence: Quotation (German Act on Copyright and Related Rights, Section 51 / § 51 UrhG)

- 1The Super Wizard Stardust, from Fletcher Hanks: “The Super Wizard Stardust: Gyp Clip’s Anti-Gravity Ray”. In: Fantastic Comics #7, 1940.Source: The Comics of Fletcher Hanks. I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets! Ed. by Paul Karasik. Seattle 2008: Fantagraphics, 42.Licence: Quotation (German Act on Copyright and Related Rights, Section 51 / § 51 UrhG)

- 2Superman’s first appearance, from Joe Shuster / Jerome Siegel: “Superman”. In: Action Comics #1. 1938.Source: Action Comics #1 50th Anniversary Reprint Edition. New York City 1988: DC Comics, 1.Licence: Quotation (German Act on Copyright and Related Rights, Section 51 / § 51 UrhG)