- Version 1.0

- published 19 August 2022

Table of content

1. Introduction

Heroes (and heroines) cross boundaries. They transgress them, thereby drawing attention to themselves and provoking social reactions. Strictly speaking, they cannot yet be called ⟶heroes during the act of crossing boundaries because they are only created through a process which begins with the transgression. In the approach discussed here, the focus is thus not on the ‘finished’ hero with his heroic attributes, but rather the various ⟶constitutive processes involved in the creation of the hero and his (her) attributes. At the (preliminary) end of the heroization process, the heroic figure appears with his quality of autonomy or transgressiveness. In this sense, the process of transgressing boundaries and thus one of several forms of boundary work which characterise ⟶heroizations is analysed below.1Cf. Schechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero as an Effect: Boundary Work in Processes of Heroization”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 17-26. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/03. For the original publication in German see Schechtriemen, Tobias: “Der ‘Held’ als Effekt. Boundary work in Heroisierungsprozessen”. In: Berliner Debatte Initial 29.1 (2018), 106-119.

2. Crossing boundaries – on the constitution of heroic transgressiveness

For boundaries to be transgressed they first need to exist. If we closely examine the formation of boundaries, however, it becomes clear that these in turn are only constituted by the transgression itself.2Michel Foucault referred to this: “The limit and transgression depend on each other for whatever density of being they possess: a limit could not exist if it were absolutely uncrossable and, reciprocally, transgression would be pointless if it merely crossed a limit composed of illusions and shadows. But can the limit have a life of its own outside of the act that gloriously passes through it and negates it?” (Foucault, Michel: “A Preface to Transgression”. In: Foucault, Michel: Language, Counter-Memory, Practice. Selected Essays and Interviews. Transl. by Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon. Ithaka, NY 1977: Cornell University Press, 29-52, 34.) Nevertheless, in every social context, we find expectations, norms and laws – and therefore boundaries. They regulate what behaviour is perceived as typical, normal or right. This framework changes historically, but it is clearly defined for the respective contemporary society.3On the various forms of bordering in the social world, see Lindemann, Gesa: “Gesellschaftliche Grenzregime und soziale Differenzierung”. In: Zeitschrift für Soziologie 38.2 (2009), 94-112. Thomas Nail distinguishes between mark, limit, boundary and frontier in his ‘Theory of the Border‘ (Nail, Thomas: Theory of the Border. Oxford 2016: Oxford University Press, 35-43). It determines what is permitted and correct in the normative sense and what is not. In addition, there are expectations about what people are ‘normally’ capable of doing and ideas about what is morally considered good and what a deviation.4On the ‘truth scenes’ of normative and moral discourses and the difference between norm violations that can be negotiated and ‘repaired’ and moral deviations where this is not possible, see Langenohl, Andreas: “Norm und Wahrheit. Soziologische Merkmale von Wahrheitsszenen”. In: Zeitschrift für Kulturphilosophie 2 (2014), 235-245. If social boundaries are transgressed, this represents an unexpected event that attracts general attention.5Markus Schroer identifies novelty as a characteristic of what is capable of generating attention (see Schroer, Markus: Soziologie der Aufmerksamkeit. Grundlegende Überlegungen zu einem Theorieprogramm. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 66 (2014), 193-218, 196-198). Eva Horn, Stefan Kaufmann and Ulrich Bröckling rightly point out that the geographically located state border is the essential reference for the rather metaphorical use of the border concept (see Kaufmann, Stefan / Bröckling, Ulrich / Horn, Eva: “Einleitung”. In: Ead. (Eds.): Grenzverletzer. Von Schmugglern, Spionen und anderen subversiven Gestalten. Berlin 2002: Kadmos, 7-22). In the accompanying volume, a variety of boundary figures are also discussed. Here, the relationality of the event becomes apparent. For what is considered completely normal against the background of the boundaries of one society is seen as a transgression in another social context with different limitations.

An example of such a transgression is the decision made by Chesley B. Sullenberger on 15 January 2009.6Amy L. Fraher also uses this example, but to explain from a psychodynamic perspective why the ‘great man hero myth’ is used here and the teamwork of the crew on board is ignored. See Fraher, Amy L.: “Hero-making as a Defence against the Anxiety of Responsibility and Risk: A Case Study of US Airways Flight 1549”. In: Organisational & Social Dynamics 11.1 (2011), 59-78. On this date, he was the captain of the US Airways flight taking off from New York’s LaGuardia Airport at 3.26 pm with 150 passengers onboard. Shortly after take-off, a severe bird strike caused both engines to fail. It was immediately clear that the plane would have to make an emergency landing within a very short space of time. Accordingly, Sullenberger had to make a quick decision. He did not follow the tower’s instructions, which first suggested a return to LaGuardia and subsequently a landing at nearby Teterboro Airport (New Jersey). Instead, Sullenberger opted for an emergency ditching on the Hudson River. Such a manoeuvre had been neither foreseen in the emergency checklists nor practised in the flight simulations. Moreover, the statistics on the chances of success were damning. Whether Sullenberger had therefore legally violated the regulations with his decision consequently became the subject of many years of legal negotiations, which ultimately ruled in his favour.7Cf. the report of the National Transportation Safety Board: Accident Report. NTSB/AAR-10/03, PB2010-910403, 2010. Online at: https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/AAR1003.pdf (accessed 10.05.2019). Irrespective of this, he definitely crossed the line of what was intended and expected – even in such an exceptional situation. It therefore remained to be seen as to how this crossing of boundaries would be evaluated socially.

The outcome of the story is well known: Sullenberger and his team (he did not act alone and it is another characteristic of heroization processes that ⟶agency is concentrated on one central figure, while the agency of all other participants is diminished in comparison) succeeded in landing on the Hudson River – between the ferries, the George Washington Bridge and less than three kilometres from Times Square in Manhattan. All passengers were able to leave the plane via the emergency exits. Images of this floating island with the survivors on the wings have become iconic (see fig. 1).

Seconds after the ditching, heroic stories began to emerge. This initially involved ‘processing’ the event through the media. Janis Krums tweeted from one of the ferries that went to the plane floating in the river: “There’s a plane in the Hudson. I’m on the ferry going to pick up the people. Crazy.”8This was the first Twitter message that was shared worldwide in a very short time and thus also made Twitter more popular. The accompanying photo can be found at http://twitpic.com/135xa (accessed 10 May 2019). What is interesting here is the reciprocal promotion of the heroic figure (Sullenberger) and the specific medium (Twitter). The end of the tweet “Crazy”, which comments on the preceding content, does not yet make an assessment, but rather describes the exceptional situation. Many television stations switched to breaking news and broadcast live images. Surveillance cameras had recorded the emergency landing, but eyewitnesses also reported and distributed their photos. In these media portrayals, the heroic narrative was quickly formed. The Governor of New York State spoke of ‘heroic deeds’ and a miracle at the scene of the accident: “We’ve had a miracle on 34th Street before. I believe now we’ve had a miracle on the Hudson.”9Reported by Quinn, James: “New York plane crash: ‘Miracle on the Hudson’ as 155 passengers survive”. In: The Telegraph, 16 January 2009. David Paterson refers to the title of the film “Miracle on 34th Street”, a US Christmas film by George Seaton from 1947, which was remade in 1994. This is a fine example of how older (hero) stories (prefigurations) are taken up and updated in the heroization process. Shortly afterwards, not only did New York Mayor, Michael Bloomberg, congratulate Sullenberger and present him with the key to the city, but the still-acting American President, George W. Bush, also thanked him via telephone.10His successor, Barack Obama, invited Sullenberger and his crew to the inauguration on 20 January. The Daily News newspaper showed the emergency landing of the plane with a portrait photo of Sullenberger on its front page (see fig. 2). The image was titled “HERO OF THE HUDSON” with the subtitle announcing the “Special report on miracle of flight 1549”. Long before a legal decision was made, society had reached its verdict: “Sully” – as the pilot was now typically called – was a hero. As such, he was interviewed on numerous talk shows, publicly honoured many times and his heroic deed was made into a film in 2016 with Clint Eastwood as director and Tom Hanks in the eponymous role.11Sully. Clint Eastwood. Warner Bros., 2016.

These societal attributions gave the historical person, Chesley B. Sullenberger, a quasi-fictional character. In this way, an idealised image of the hero or heroine is created through the heroization process.12Orrin E. Klapp points out the various phases of heroization, which he also counts as “the building up of an idealised image or legend of the hero” (Klapp, Orrin E.: “Hero Worship in America”. In: American Sociological Review 14.1 (1949), 53-62, 54). However, idealisation also includes the possibility that the historical person cannot live up to the expectations placed on him or her (see Klapp: “Hero Worship in America”, 1949, 60). In doing so, the person is idealised and thus detached from their direct social context and literarised. “What is interesting is the way in which the image of the hero is taken out of its context and woven into a heroic life in which the social context becomes played down, or becomes one in which the hero distinguishes himself from and rises above the social.”13Featherstone, Mike: “The Heroic Life and Everyday Life”. In: Theory, Culture and Society 9 (1992), 159-182, 168. Accordingly, accounts of Sully show clear similarities with fictional hero narratives in their dynamics and structure. Whether a historical event forms the starting point, or it is a purely fictional story makes a considerable difference to social perception and scholarly framing.14On the indicators that distinguish fictional from factual texts – here related to the genre of biography – see Nünning, Ansgar: “Fiktionalität, Faktizität, Metafiktion”. In: Klein, Christian (Ed.): Handbuch Biographie. Methods, Traditions, Theories. Stuttgart 2009: J.B. Metzler Verlag, 21-27, 25f. But regarding the way the hero story is told and how the boundary work in it functions, there are many parallels.15Frisk, Kristian: “What Makes a Hero? Theorising the Social Structuring of Heroism”. In: Sociology 53.1 (2018), 1-17, 6-7. In this respect, analytical tools from literary studies can also be used to examine social-media forms of communication. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen whether, in the real heroization process, there is a complex initial situation with many actors involved – but still without heroes – as well as a moment of ambiguity whose evaluation remains open.

The transgression of boundaries is retrospectively represented within the framework of the hero narrative and can then be analysed. According to Juri Lotman, the world of heroic stories always has a central demarcation separating “two mutually complementary subsets”.16Lotman, Jurij M.: The Structure of the Artistic Text, Ann Arbor 1977: University of Michigan, 240. Of these two sides exists a realm of ordinary mortals and a beyond that cannot be entered by the former. The protagonist now distinguishes himself precisely by transgressing this boundary, which is binding for all others and considered uncrossable.17If you look at the other characters in the narrative, there will often be companion characters who do not manage to cross the boundary. Part of the narrative design is the description of the sheer insurmountability of the boundary, because the greatness of the heroic deed is measured by the greatness of the challenge. It is precisely in the contrast to the normal that the extraordinariness of heroic action becomes apparent. “The agent is the one who crosses the border of the plot field (the semantic field), and the border for the agent is a barrier.”18Lotman: The Structure of the Artistic Text, 1977, 240. It is through the act of crossing the boundary that the heroic figure is actually constituted as such.19 Bernhard Giesen also describes heroes (along with perpetrators and victims) as boundary figures and as “imaginings and projections of a community that looks across the boundary into the darkness and seeks to still its uneasiness through stories and images of the uncanny world beyond the frontier.” (Giesen, Bernhard: “Zur Phänomenologie der Ausnahme: Helden, Täter, Opfer”. In: Giesen, Bernhard: Zwischenlagen. Das Außerordentliche als Grund der sozialen Wirklichkeit. Weilerswist 2010: Velbrück, 67-87, 86). Here, the procedural nature of heroization becomes very clear. It is the act of crossing over that changes the figure who transgresses and gives them heroic qualities.20“Once the agent has crossed the border, he enters another semantic field, an ‘anti-field’ vis-a-vis the initial one.” (Lotman: The Structure of the Artistic Text, 1977, 241.) In the sense of the hero’s journey as described by Vladimir J. Propp and Joseph Campbell, it is in the foreign land where the hero must prove himself before returning home changed.

Crossing the boundary is always the exception. If it were the rule, the corresponding boundary would not exist.21Simultaneously, social laws are not directly challenged by the transgression, as would be the case with natural laws (see also Langenohl, Andreas: “Norm und Wahrheit. Soziologische Merkmale von Wahrheitsszenen”. In: Zeitschrift für Kulturphilosophie 2 (2014), 235-245, 237). Due to its exceptional character and because the transgression questions existing boundaries, it provokes a social reaction and generates narrative tension. If it is a real event, society must react to the transgression, precisely because the transgressive action challenges social normality and normativity. In the example above, it is the plane on its way astray over New York – especially after the attacks of 11 September 2001 – which leaves its element, the air, and lands on water. Sometimes, however, it also applies to the social reception of fictional narratives: The specific form of heroic representations, their human – and mostly male22Frisk: “What Makes a Hero?”, 2018, 11. – personalisation, the concentration of agency on a central figure, their reference to the numinous23This reference is articulated, for example, in the radiance, the éclat of the hero. Cf. Willis, Jakob: Glanz und Blendung. Zur Ästhetik des Heroischen im Drama des Siècle classique. Bielefeld 2017: transcript; as well as Gelz, Andreas: “The Radiance of the Hero. Representations of the Heroic in French Literature from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 97-108. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/10 (for the original publication in German see Gelz, Andreas: “Der Glanz des Helden – Darstellungsformen des Heroischen in der französischen Literatur vom 17.–19. Jahrhundert”. In: französisch heute 49.2 (2018), 5-13). as well as their polarised setting evoke strongly affirmative effects. Accordingly, boundary crossings are evocative events from which society emerges altered to a greater or lesser degree.24The interplay between affective effects and the emergence of new forms of the social is addressed, for example, by Stäheli, Urs: “Infrastrukturen des Kollektiven: alte Medien – neue Kollektive?”. In: Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturforschung 2 (2012), 99-116 and Slaby, Jan / Mühlhoff, Rainer / Wüschner, Philipp: “Affective Arrangements”. In: Emotion Review 11.1 (2017), 1-10. On the boundary itself, the transgression can have the effect of stabilisation, but also of displacement or dissolution. Heroes can be both the starting point of social upheavals and serve to stabilise existing orders.

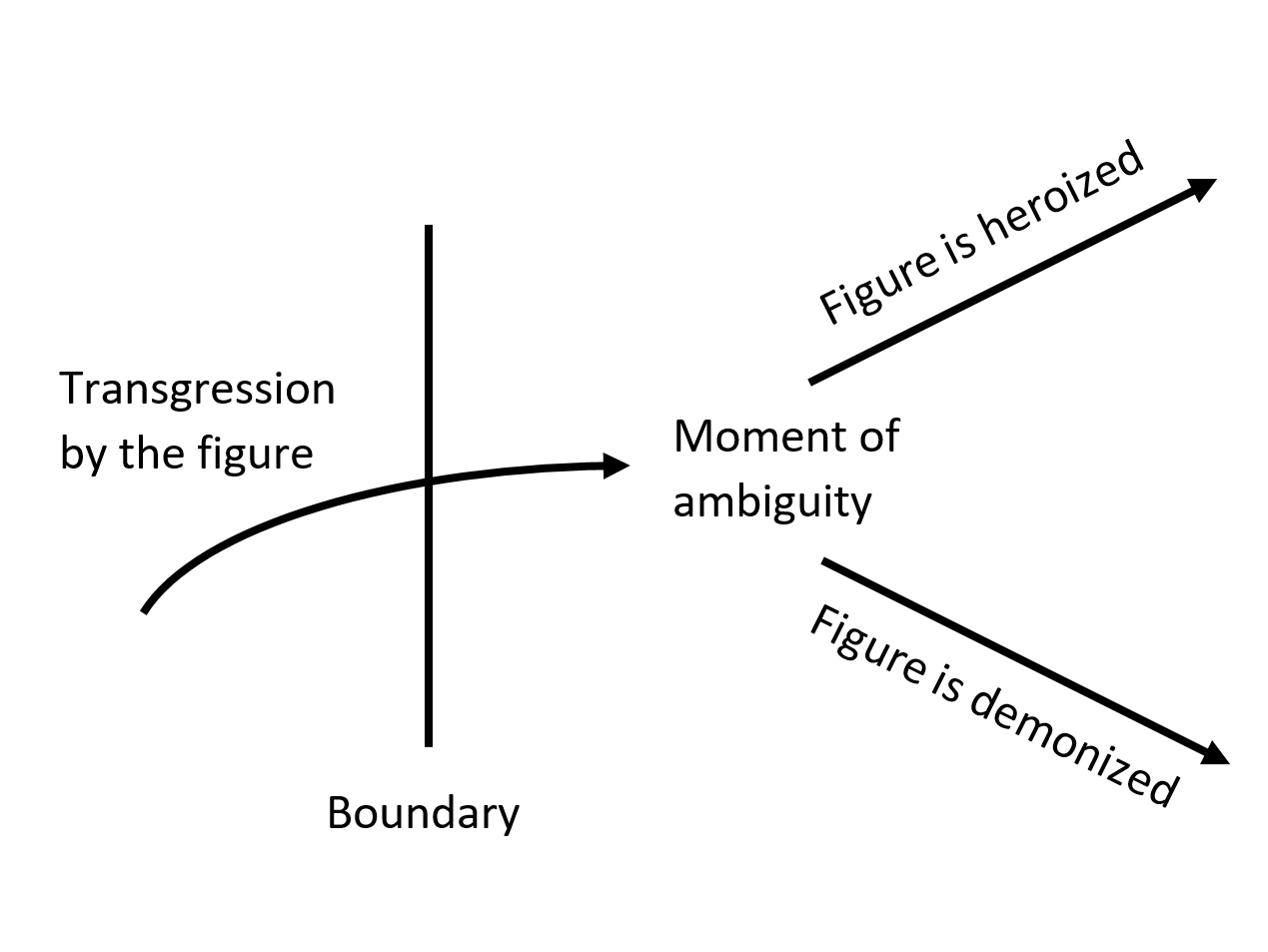

The transgression of boundaries is followed by a moment of ambiguity in which the transgression of the law is either heroized or demonised. It is interesting to note that there are only these two diametrically opposed possibilities – those involved do not usually react indifferently.25It is conceivable that the negotiation of the social response to the boundary transgression does not emerge relatively quickly – as in the example given – but in a more protracted process. Therein lie the limitations of the heuristic example proposed here: it suggests that it is an ambiguous moment – but sometimes a longer period – and that with heroization all ‘demonic’ aspects would be resolved. This does not mean that the heroized figure is then completely ‘purged’. Often ambivalences and negative characteristics persist, sometimes contributing to the attractiveness of the admired figure. Sullenberger’s boundary crossing was widely viewed positively, as ‘heroic’, as shown above. But for aviation regulations and the corresponding training of future pilots, this assessment was definitely a challenge. After all, the deviant behaviour here should not act as the shining example and become the rule. Moreover, one can imagine what the social evaluation would have looked like had the ditching not been successful.

Through analysis it becomes clear that how transgression is socially evaluated is at first undecided. This indecision is concealed in the hero narrative that emerges through the course of the process. Within the framework of the hero narrative, the ultimate hero figure is usually portrayed from the beginning in such a way that, for example, their heroic character had already shown itself in childhood. However, if one analyses the heroization process in its various phases, the openness of the evaluation immediately after the boundary crossing becomes apparent. Only then do the questions arise as to how the heroic story was formed in the media and which different orders of justification played a role in its social evaluation. In addition, one can ask about the factors concerning the person that make the transgression more likely to be heroized, such as the fact that the transgressive act was done out of one’s own free will and not out of compulsion, that a personal risk was accepted in the process, and that the outcome was open.26For these and other helpful suggestions, I would like to thank Georg Feitscher and the collaborative research group “Syntheses” of the SFB 948. It is interesting here that both failure (as a tragic hero) and success (triumphant hero) can be heroized.27Giesen, Bernhard: Triumph and Trauma. Boulder, CO 2004: Paradigm Publishers.

In summary, it can be stated that over the course of the heroization process, there is initially a transgression of boundaries by a person, followed by a moment of ambiguity in which it is unclear as to how the social environment in question will react to it (the only thing that is certain is that there can be no ‘business as usual’ as a reaction). In the case of positive evaluation, a heroic narrative and other media representations of heroes emerge (see fig. 3). During this process, the heroic figure is attributed the quality of autonomy and transgressiveness.

3. References

- 1Cf. Schechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero as an Effect: Boundary Work in Processes of Heroization”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 17-26. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/03. For the original publication in German see Schechtriemen, Tobias: “Der ‘Held’ als Effekt. Boundary work in Heroisierungsprozessen”. In: Berliner Debatte Initial 29.1 (2018), 106-119.

- 2Michel Foucault referred to this: “The limit and transgression depend on each other for whatever density of being they possess: a limit could not exist if it were absolutely uncrossable and, reciprocally, transgression would be pointless if it merely crossed a limit composed of illusions and shadows. But can the limit have a life of its own outside of the act that gloriously passes through it and negates it?” (Foucault, Michel: “A Preface to Transgression”. In: Foucault, Michel: Language, Counter-Memory, Practice. Selected Essays and Interviews. Transl. by Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon. Ithaka, NY 1977: Cornell University Press, 29-52, 34.)

- 3On the various forms of bordering in the social world, see Lindemann, Gesa: “Gesellschaftliche Grenzregime und soziale Differenzierung”. In: Zeitschrift für Soziologie 38.2 (2009), 94-112. Thomas Nail distinguishes between mark, limit, boundary and frontier in his ‘Theory of the Border‘ (Nail, Thomas: Theory of the Border. Oxford 2016: Oxford University Press, 35-43).

- 4On the ‘truth scenes’ of normative and moral discourses and the difference between norm violations that can be negotiated and ‘repaired’ and moral deviations where this is not possible, see Langenohl, Andreas: “Norm und Wahrheit. Soziologische Merkmale von Wahrheitsszenen”. In: Zeitschrift für Kulturphilosophie 2 (2014), 235-245.

- 5Markus Schroer identifies novelty as a characteristic of what is capable of generating attention (see Schroer, Markus: Soziologie der Aufmerksamkeit. Grundlegende Überlegungen zu einem Theorieprogramm. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 66 (2014), 193-218, 196-198). Eva Horn, Stefan Kaufmann and Ulrich Bröckling rightly point out that the geographically located state border is the essential reference for the rather metaphorical use of the border concept (see Kaufmann, Stefan / Bröckling, Ulrich / Horn, Eva: “Einleitung”. In: Ead. (Eds.): Grenzverletzer. Von Schmugglern, Spionen und anderen subversiven Gestalten. Berlin 2002: Kadmos, 7-22). In the accompanying volume, a variety of boundary figures are also discussed.

- 6Amy L. Fraher also uses this example, but to explain from a psychodynamic perspective why the ‘great man hero myth’ is used here and the teamwork of the crew on board is ignored. See Fraher, Amy L.: “Hero-making as a Defence against the Anxiety of Responsibility and Risk: A Case Study of US Airways Flight 1549”. In: Organisational & Social Dynamics 11.1 (2011), 59-78.

- 7Cf. the report of the National Transportation Safety Board: Accident Report. NTSB/AAR-10/03, PB2010-910403, 2010. Online at: https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/AAR1003.pdf (accessed 10.05.2019).

- 8This was the first Twitter message that was shared worldwide in a very short time and thus also made Twitter more popular. The accompanying photo can be found at http://twitpic.com/135xa (accessed 10 May 2019). What is interesting here is the reciprocal promotion of the heroic figure (Sullenberger) and the specific medium (Twitter). The end of the tweet “Crazy”, which comments on the preceding content, does not yet make an assessment, but rather describes the exceptional situation.

- 9Reported by Quinn, James: “New York plane crash: ‘Miracle on the Hudson’ as 155 passengers survive”. In: The Telegraph, 16 January 2009. David Paterson refers to the title of the film “Miracle on 34th Street”, a US Christmas film by George Seaton from 1947, which was remade in 1994. This is a fine example of how older (hero) stories (prefigurations) are taken up and updated in the heroization process.

- 10His successor, Barack Obama, invited Sullenberger and his crew to the inauguration on 20 January.

- 11Sully. Clint Eastwood. Warner Bros., 2016.

- 12Orrin E. Klapp points out the various phases of heroization, which he also counts as “the building up of an idealised image or legend of the hero” (Klapp, Orrin E.: “Hero Worship in America”. In: American Sociological Review 14.1 (1949), 53-62, 54). However, idealisation also includes the possibility that the historical person cannot live up to the expectations placed on him or her (see Klapp: “Hero Worship in America”, 1949, 60).

- 13Featherstone, Mike: “The Heroic Life and Everyday Life”. In: Theory, Culture and Society 9 (1992), 159-182, 168.

- 14On the indicators that distinguish fictional from factual texts – here related to the genre of biography – see Nünning, Ansgar: “Fiktionalität, Faktizität, Metafiktion”. In: Klein, Christian (Ed.): Handbuch Biographie. Methods, Traditions, Theories. Stuttgart 2009: J.B. Metzler Verlag, 21-27, 25f.

- 15Frisk, Kristian: “What Makes a Hero? Theorising the Social Structuring of Heroism”. In: Sociology 53.1 (2018), 1-17, 6-7.

- 16Lotman, Jurij M.: The Structure of the Artistic Text, Ann Arbor 1977: University of Michigan, 240.

- 17If you look at the other characters in the narrative, there will often be companion characters who do not manage to cross the boundary. Part of the narrative design is the description of the sheer insurmountability of the boundary, because the greatness of the heroic deed is measured by the greatness of the challenge. It is precisely in the contrast to the normal that the extraordinariness of heroic action becomes apparent.

- 18Lotman: The Structure of the Artistic Text, 1977, 240.

- 19Bernhard Giesen also describes heroes (along with perpetrators and victims) as boundary figures and as “imaginings and projections of a community that looks across the boundary into the darkness and seeks to still its uneasiness through stories and images of the uncanny world beyond the frontier.” (Giesen, Bernhard: “Zur Phänomenologie der Ausnahme: Helden, Täter, Opfer”. In: Giesen, Bernhard: Zwischenlagen. Das Außerordentliche als Grund der sozialen Wirklichkeit. Weilerswist 2010: Velbrück, 67-87, 86).

- 20“Once the agent has crossed the border, he enters another semantic field, an ‘anti-field’ vis-a-vis the initial one.” (Lotman: The Structure of the Artistic Text, 1977, 241.) In the sense of the hero’s journey as described by Vladimir J. Propp and Joseph Campbell, it is in the foreign land where the hero must prove himself before returning home changed.

- 21Simultaneously, social laws are not directly challenged by the transgression, as would be the case with natural laws (see also Langenohl, Andreas: “Norm und Wahrheit. Soziologische Merkmale von Wahrheitsszenen”. In: Zeitschrift für Kulturphilosophie 2 (2014), 235-245, 237).

- 22Frisk: “What Makes a Hero?”, 2018, 11.

- 23This reference is articulated, for example, in the radiance, the éclat of the hero. Cf. Willis, Jakob: Glanz und Blendung. Zur Ästhetik des Heroischen im Drama des Siècle classique. Bielefeld 2017: transcript; as well as Gelz, Andreas: “The Radiance of the Hero. Representations of the Heroic in French Literature from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 97-108. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/10 (for the original publication in German see Gelz, Andreas: “Der Glanz des Helden – Darstellungsformen des Heroischen in der französischen Literatur vom 17.–19. Jahrhundert”. In: französisch heute 49.2 (2018), 5-13).

- 24The interplay between affective effects and the emergence of new forms of the social is addressed, for example, by Stäheli, Urs: “Infrastrukturen des Kollektiven: alte Medien – neue Kollektive?”. In: Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturforschung 2 (2012), 99-116 and Slaby, Jan / Mühlhoff, Rainer / Wüschner, Philipp: “Affective Arrangements”. In: Emotion Review 11.1 (2017), 1-10. On the boundary itself, the transgression can have the effect of stabilisation, but also of displacement or dissolution.

- 25It is conceivable that the negotiation of the social response to the boundary transgression does not emerge relatively quickly – as in the example given – but in a more protracted process. Therein lie the limitations of the heuristic example proposed here: it suggests that it is an ambiguous moment – but sometimes a longer period – and that with heroization all ‘demonic’ aspects would be resolved.

- 26For these and other helpful suggestions, I would like to thank Georg Feitscher and the collaborative research group “Syntheses” of the SFB 948.

- 27Giesen, Bernhard: Triumph and Trauma. Boulder, CO 2004: Paradigm Publishers.

4. Selected literature

- Featherstone, Mike: “The Heroic Life and Everyday Life”. In: Theory, Culture and Society 9 (1992), 159-182.

- Foucault, Michel: “A Preface to Transgression”. In: Foucault, Michel: Language, Counter-Memory, Practice. Selected Essays and Interviews. Transl. by Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon. Ithaka, NY 1977: Cornell University Press, 29-52.

- Fraher, Amy L.: “Hero-making as a Defence against the Anxiety of Responsibility and Risk: A Case Study of US Airways Flight 1549”. In: Organisational & Social Dynamics 11.1 (2011), 59-78.

- Frisk, Kristian: “What Makes a Hero? Theorising the Social Structuring of Heroism”. In: Sociology 53.1 (2018), 1-17.

- Gelz, Andreas: “The Radiance of the Hero. Representations of the Heroic in French Literature from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 97-108. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/10.

- Giesen, Bernhard: Triumph and Trauma. Boulder, CO 2004: Paradigm Publishers.

- Giesen, Bernhard: “Zur Phänomenologie der Ausnahme: Helden, Täter, Opfer”. In: Giesen, Bernhard: Zwischenlagen. Das Außerordentliche als Grund der sozialen Wirklichkeit. Weilerswist 2010: Velbrück, 67-87.

- Kaufmann, Stefan / Bröckling, Ulrich / Horn, Eva: “Einleitung”. In: Ead. (Eds.): Grenzverletzer. Von Schmugglern, Spionen und anderen subversiven Gestalten. Berlin 2002: Kadmos, 7-22.

- Klapp, Orrin E.: “Hero Worship in America”. In: American Sociological Review 14.1 (1949), 53-62.

- Langenohl, Andreas: “Norm und Wahrheit. Soziologische Merkmale von Wahrheitsszenen”. In: Zeitschrift für Kulturphilosophie 2 (2014), 235-245.

- Lindemann, Gesa: “Gesellschaftliche Grenzregime und soziale Differenzierung”. In: Zeitschrift für Soziologie 38.2 (2009), 94-112.

- Lotman, Jurij M.: The Structure of the Artistic Text, Ann Arbor 1977: University of Michigan.

- Nail, Thomas: Theory of the Border. Oxford 2016: Oxford University Press.

- National Transportation Safety Board: Accident Report. NTSB/AAR-10/03, PB2010-910403, 2010. Online at: https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/AAR1003.pdf (Accessed on 10.05.2019).

- Nünning, Ansgar: “Fiktionalität, Faktizität, Metafiktion”. In: Klein, Christian (Ed.): Handbuch Biographie. Methoden, Traditionen, Theorien. Stuttgart 2009: J.B. Metzler Verlag, 21-27.

- Quinn, James: “New York plane crash: ‘Miracle on the Hudson’ as 155 passengers survive”. In: The Telegraph, 16 January 2009.

- Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero as an Effect. Boundary Work in Processes of Heroization”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 17-26. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/03

- Schroer, Markus: Soziologie der Aufmerksamkeit. Grundlegende Überlegungen zu einem Theorieprogramm. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 66 (2014), 193-218.

- Slaby, Jan / Mühlhoff, Rainer / Wüschner, Philipp: “Affective Arrangements”. In: Emotion Review 11.1 (2017), 1-10.

- Stäheli, Urs: “Infrastrukturen des Kollektiven: alte Medien – neue Kollektive?”. In: Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturforschung 2 (2012), 99-116.

- Willis, Jakob: Glanz und Blendung. Zur Ästhetik des Heroischen im Drama des Siècle classique. Bielefeld 2017: transcript.

5. List of images

- Foto des notgewasserten US-Airways-Fluges 1549 im Hudson RiverLicence: Creative Commons BY 2.0

- 1Photo of the ditched US Airways Flight 1549 in the Hudson RiverLicence: Creative Commons BY 2.0

- 2Front cover of the Daily News, Friday, 16 January 2009, New YorkSource: New York Daily NewsLicence: Copyrighted image / quotation (German Act on Copyright and Related Rights, Section 51 / § 51 UrhG)

- 3Visualisation of the trangression processSource: Own work by Tobias SchlechtriemenLicence: Creative Commons BY-ND 4.0