- Version 1.0

- published 11 January 2023

Table of content

- 1. Overview

- 2. The industrialisation of warfare and its consequences for the image of the soldier

- 2.1. Warfare on the road to modernity

- 2.2. Militarization of European societies

- 2.3. War reporting and mass media

- 3. Phenomena and forms of representation of soldierly heroism

- 3.1. Soldierly heroism in modern warfare

- 3.2. The First World War as a rupture of the heroic

- 3.3. Soldierly attributes

- 3.4. Mechanised chivalry

- 3.5. Soldier-heroes after the ‘Great War’

- 3.6. Soldierly heroism in the remembrance culture of the post-war period

- 3.7. Freedom fighters as soldiers

- 4. References

- 5. Selected literature

- 6. List of images

- Citation

1. Overview

The image of the soldier underwent profound change from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, linked to the industrialisation of warfare and the closer connection between the conflict and the community at home. This new type of mass warfare was increasingly difficult to reconcile with the traditional conception of the war hero.1Schilling, René: “Kriegshelden”. Deutungsmuster heroischer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1813–1945. Paderborn 2002: Schöningh; Wulff, Aiko: “‘Mit dieser Fahne in der Hand’. Materielle Kultur und Heldenverehrung 1871–1945”. In: Historical Social Research 34/4 (2009), 343-355. Notions of the heroic also changed in response to the political and economic conditions of the emerging modern era.2Voss, Dietmar: “Heldenkonstruktionen. Zur modernen Entwicklungstypologie des Heroischen”. In: KulturPoetik/Journal for Cultural Poetics 11 (2011), 181-202. The First World War ultimately represented a watershed in which the figure of the soldierly hero and its relation to modernity were renegotiated.3Esposito, Fernando: “‘Über keinem Gipfel ist Ruh’. Helden- und Kriegertum als Topoi medialisierter Kriegserfahrungen deutscher und italienischer Flieger”. In: Kuprian, Hermann (Ed.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung. Innsbruck 2006: Wagner, 73-90.

2. The industrialisation of warfare and its consequences for the image of the soldier

2.1. Warfare on the road to modernity

In the mid-19th century, warfare in Western countries began to change. Technical innovations such as the needle gun or the mitrailleuse were influencing both strategy and tactics. Whilst, during the Crimean War of 1853–1856, soldiers still advanced towards each other in long line formations, the advantage of modern weapons for defensively entrenched units was already noticeable during the siege of Sevastopol in 1854/1855. Developments in weapons technology led to the obsolescence of the military tactics that had still been being used successfully in the first half of the century. However, it was not only military technology that changed, but also the increasing importance of political leadership, which had to coordinate armed forces as well as mobilise civil society at home for the war effort. During the American Civil War of 1861–1865, these two developments became apparent for the first time in a Western theatre of war. Barbed wire, trenches, landmines, and artillery fire were not inventions of the First World War; they had already been tested in the middle of the century and changed the soldierly experience.4Ven, Hans van de: “A hinge in time: the wars of the mid nineteenth century”. In: Chickering, Roger / Showalter, Dennis / Ven, Hans van de (Eds.): The Cambridge History of War: War and the Modern World. Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, 16-44. However, despite the new technological developments, the individual soldier did not lose his place in the military doctrines of European countries. It was only towards the end of the 19th century that the ideal of an autonomous soldier was exchanged for that of a mass army, for example in the early 1880s in the Third French Republic.5Drévillon, Hervé: L’Individu et la Guerre. Du chevalier Bayard au Soldat inconnu. Paris 2013: Seuil, 215-216, 239-250. The major military campaigns of the second half of the century also saw the deployment of colonial troops, which led to the emergence of new ⟶heroic figures. The Zouaves in the French army, for example, were incorporated into heroic narratives that spread a mixture of exotic and mythical warrior ideals that contrasted with European soldiers. However, the depiction of colonial troops was tainted by racist stereotypes and notions of African or Oriental savagery.6Drévillon: L’Individu et la Guerre, 2013, 215-216.

2.2. Militarization of European societies

The introduction of compulsory military service during the last third of the 19th century had a major influence on the image of soldiers in Western European societies. While this was viewed with scepticism by most states after the Napoleonic Wars, as it was feared that democratic principles would be thereby extended, Prussian successes after the 1860s demonstrated the advantages of general conscription, which had already been introduced there in 1814. Other states such as France or Russia continued to rely on selective conscription with extensive exceptions. Only after the victory of Prussia and its German allies over France in 1870/71 did other states adopt universal conscription with a large force of reserves.7Chickering, Roger: “War, society, and culture, 1850–1914: the rise of militarism”. In: Chickering, Roger / Showalter, Dennis / Ven, Hans van de (Eds.): The Cambridge History of War: War and the Modern World. Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, 119-141, 120-122.

Towards the end of the century there was, therefore, a more comprehensive democratisation of the soldier, which at the same time became more closely linked to civil society. The male population was now almost invariably educated about military virtues, which included attributes such as strength, heroism, discipline, unity, obedience to authority and sacrifice for the nation. These same values consolidated the notion of conscription as a civic duty and also underscored the seeming inevitability of war. Accordingly, the military occupied an ever-greater place in Western European societies and thus led to a popularisation of the soldier imagined as heroic, who would sacrifice his life for the fatherland in an emergency.8Chickering: “War, society, and culture”, 2012, 124-125. Even though the influence of such militarisation on the societies concerned is difficult to quantify, it can be assumed that towards the end of the 19th century a romantically transfigured idea of soldiers and of warfare was widespread and no longer corresponded to the realities of modern war.9Vogel, Jakob: “Der ‘Folklorenmilitarismus’ und seine zeitgenössische Kritik: Deutschland und Frankreich, 1871–1914”. In: Wette, Wolfram (Ed.): Militarismus in Deutschland 1871 bis 1945. Zeitgenössische Analysen und Kritik. Münster 1999: LIT, 277-292.

2.3. War reporting and mass media

However, these developments alone were not enough to change the idea of soldierly heroism in Western European societies. Without the new type of war reporting that kept civil societies informed of events on the front, such a change could not have taken place. Thus, the Crimean War was the first major conflict in which professional war correspondents wrote not only about the developments of the fighting, but also about the deeds and sufferings of ordinary soldiers. Thanks to improved means of transport, and telegraphy, these reports could reach European societies relatively quickly.10Daniel, Ute: “Der Krimkrieg 1853–56 und die Entstehungsgeschichte medialer Kriegsberichterstattung”. In: Daniel, Ute (Ed.): Augenzeugen. Kriegsberichterstattung vom 18. zum 21. Jahrhundert. Göttingen 2006: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 40-67. Thus, the war reports published in newspapers brought many tales of heroic deeds of ordinary soldiers closer to the British readership and thus created a broader public awareness of a soldierly type of hero for the first time. Simultaneously, public interest in honouring these ordinary men in uniform increased.11Figes, Orlando: Crimea. The last Crusade. London 2011: Allen Lane, 467-472. War as a media event12Cf. for example: Steinsieck, Andreas: “Ein imperialistischer Medienkrieg. War correspondents in the South African War (1889-1902)”. In: Daniel, Ute (Ed.): Augenzeugen. War Reporting from the 18th to the 21st Century. Göttingen 2006: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 87-112. consequently had a major influence on the change in the image of soldiers in Western European societies.

3. Phenomena and forms of representation of soldierly heroism

3.1. Soldierly heroism in modern warfare

The Crimean War, above all, changed the British public’s attitude towards its soldiers. It was the basis for a modern national myth in which soldiers allegedly fought for national honour, for justice and freedom. Chivalry and heroism had previously been represented by aristocratic military leaders; military paintings, for example, usually showed noble officers in heroic battles. The common soldier was usually ignored. The erection of the Guards Crimean War Memorial symbolised a turning point in Victorian attitudes to soldierly heroism. (See fig. 2.) It represented an attack on the aristocratic claim to leadership within the military, which had proved disastrous during the Crimean War. If the British hero had previously been imagined as a ‘groomed’ gentleman, he was now a trooper, a ‘Private Smith’ or a ‘Tommy’13In Rudyard Kipling’s eponymous poem from 1890, a fictitious “Tommy” addresses the inherent ambiguity of being ascribed heroic status while still being treated like an ordinary soldier: “O it’s ‘Thin red line of ’eroes’ when the drums begin to roll. / We aren’t no thin red ’eroes, nor we aren’t no blackguards too, / But single men in barricks, most remarkable like you; … “ Online at: https://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poem/poems_tommy.htm (accessed 2022-12-21). of folklore who fought bravely and brought victory to the motherland despite the mistakes of the British generals. This narrative persisted into the First World War.

The introduction of the Victoria Cross to honour the achievements of ordinary soldiers finally gave official recognition to this development. In other countries, however, similar forms of recognition had already existed for some time, for example in France since 1802 with the Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur or in Prussia since 1813 with the Iron Cross.14The Iron Cross, endowed in Prussia in 1813, was intended not only to strengthen soldiers’ ties with the army, but also their willingness to go to war for their nation. Clark, Christopher: Preußen. Aufstieg und Niedergang 1600–1947, Munich 2007: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 434-435 The creation of the Victoria Cross demonstrates a change in the idea of heroism, and not only in its official symbolism. Soldiers who received this award became important reference points for commemorative events and a popular remembrance culture. A large number of post-war books also glorified the courage of ordinary soldiers from the 1850s onwards.15Figes: “Crimea”, 2011, 472. In addition, a new religious subtext within soldiery emerged during the Crimean War. The suffering clearly described in the newspapers changed the image of soldiers among the British upper and middle classes. Whereas the ordinary soldier had previously been a drinking, undisciplined brawler, he now became a faithful Christian who accomplished the will of God through his martyrdom.16Figes: “Crimea”, 2011, 472. For the rest of Western Europe, however, the Crimean War did not have the same impact. For France, the German states, the Habsburg monarchy and Italy, the wars of the 1860s were to prove more significant points of reference. In these wars, too, however, the novel connection between the military front and civil society led to a similar change in the notion of the soldier and to closer links between the battles and civic society.17Becker, Frank: “Deutschland im Krieg von 1870/71 oder die mediale Inszenierung der nationalen Einheit”. In: Daniel, Ute (Ed.): Augenzeugen. Kriegsberichterstattung vom 18. zum 21. Jahrhundert. Göttingen 2006: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 68-86.

3.2. The First World War as a rupture of the heroic

The First World War reconfigured assumptions about military heroism. If developments since the Atlantic Revolutions and the Napoleonic Wars had led to a democratisation of military heroism, this process culminated on the battlefields of the First World War.18Frevert, Ute: “Herren und Helden. Vom Aufstieg und Niedergang des Heroismus im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert”. In: Dülmen, Richard van (Ed.): Erfindung des Menschen. Schöpfungsträume und Körperbilder 1500–2000. Vienna/Cologne /Weimar 1998: Böhlau, 323-344. The anonymised war of mass destruction marginalised the significance of the individual subject and thus effectively excluded the possibility of heroism on the battlefield – at least in tactical war. In regions that were not marked by the stalemate on the fronts, individuals were able to stand out and in some cases were built up as heroic figures in the media in their home society – for example, T. E. Lawrence, who as a mixture of soldier and adventurer still elicits great fascination.19Carchidi, Victoria: Creation out of the void: The making of a hero, an epic, a world: T. E. Lawrence, (Dissertation University of Pennsylvania 1987). Ann Arbor 1987: UMI Dissertation Services. Online at: https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI8804889 (accessed 2023-01-11); Korda, Michael: Hero. The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia. New York et al. 2010: Harper.

Nevertheless, on the European Western Front especially, the suffering, the anonymity of the battlefields and the enormous fatalities led to death losing its heroic potential, and to the fallen being assigned a victim role. While it was still possible to commemorate the heroically fallen in the American Civil War or the Franco-Prussian War in the second half of the 19th century, the dead of the First World War were reinterpreted as victims of this conflict.20Capdevila, Luc / Voldman, Danièle: War Dead. Western Societies and the Casualties of War. Edinburgh 2006: Edinburgh University Press, 10-12. In the soldier’s self-perception in particular, there was a corresponding disillusionment, itself a product of the Enlightenment and Romanticism.21Harari, Yuval N.: The Ultimate Experience. Battlefield Revelations and the Making of Modern War Culture, 1450–2000. Basingstoke 2008: Palgrave Macmillan. The expectations of many soldiers were disappointed above all by the absence of an offensive war imagined as heroic, buried instead in the positions and trenches by artillery fire.22Frevert: “Herren und Helden”, 1998, 339-340. The inflationary distribution of military awards also discredited this potential source of military heroism.23Kienitz, Sabine: Beschädigte Helden. Kriegsinvalidität und Körperbilder 1914–1923. Paderborn 2003: Schöningh, 79-94. However, it cannot be said that soldierly heroes were no longer seen in the societies of the homeland. Werner Sombart and Georg Simmel, for example, transferred their ideal conceptions of the German people to the fighting soldiers, who became the prototype of a “neuer Mensch” (“new man”) through their heroically imagined struggle in the trenches. From this point of view, the type of soldier-hero did not need a specific individual to enable ⟶adoration. Rather, the imagined collective concept of the soldier formed a surface for the projection of longings and expectations that were to be fulfilled through the soldie’s heroic struggle.24Schnyder, Peter: “Erlösung von der Medialität? ‘Held’ und ‘neuer Mensch’ in der Kriegsrhetorik von Simmel und Sombart”. In: Baumgartner, Stephan / Gamper, Michael / Wagner, Karl (Eds.): Der Held im Schützengraben. Führer, Massen und Medientechnik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Zürich 2014: Chronos, 29-50.

Another development that reached a temporary peak during the First World War was the close connection between the frontlines and home. This required that new heroic narratives had to be found on the so-called home front of the belligerent states, which counteracted the impression of the industrially conducted mass war. New possibilities of controlling the mass media were used, among other things, to convey heroic figures that were supposed to contribute to a comprehensive mobilisation of society (see also ⟶propaganda).25Daniel, Ute: “Informelle Kommunikation und Propaganda in der deutschen Kriegsgesellschaft”. In: Quandt, Siegfried / Schichtel, Horst (Eds.): Der Erste Weltkrieg als Kommunikationsereignis. Gießen 1993: Universität Gießen FB Fachjournalistik, 76-93; Forcade, Olivier: “Information, censure et propagande”. In: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques (Eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, 1914–1918: histoire et culture. Paris 2004: Bayard, 451-466; Verhey, Jeffrey: “Krieg und geistige Mobilmachung: Die Kriegspropaganda”. In: Kruse, Wolfgang (Ed.): Eine Welt von Feinden. Der Große Krieg 1914–1918. Frankfurt a. M. 1997: Fischer, 177-178; Winter, Jay: “Propaganda and the mobilization of consent”. In: Strachan, Hew (Ed.): The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, Oxford 2000: Oxford University Press, 25-40. Accordingly, attempts were made to stylise individual figures as heroes in the media, which, however, only led to a long-term adoration of soldiers in exceptional cases.26Schneider, Gerhard: “Heldenkult”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (Eds.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2009: Schöningh, 550-551.

3.3. Soldierly attributes

During the First World War, military heroism was transferred to the entire ⟶collective of soldiers for the first time. After the battles at Verdun and on the Somme, the heroic-soldierly attributes of suffering, ⟶perseverance and standing firm, of willingness to make sacrifices and of manliness fulfilled a role model function at the front and at home. Thus, every soldier could theoretically be a hero without having a definable community of admirers.27Schneider: “Heldenkult”, 2009, 550-551.

The culmination of this process after the war was the cult of the allegorical figure of the Unknown Soldier, who was regarded as the epitome of the heroic soldierly sacrifice.28Ackermann, Volker: “‘Ceux qui sont pieusement morts pour la France…’ Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 281-314; Koselleck, Reinhart: “Einleitung”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 9-20. This development also had an impact on individual military heroes, who themselves could not do without soldierly attributes or who were placed in the vicinity of the soldierly hero collective, such as the generals Paul von Hindenburg, Philippe Pétain or Ferdinand Foch, who were celebrated as heroes.29In France, for example, a heroic figure like Philippe Pétain was distinguished by his close relationship with the soldiers under his command, Paul von Hindenburg was endowed with soldierly attributes, Gabrielle D’Annunzio was regarded as the epitome of bravery and masculinity. Gildea, Robert / Goltz, Anna von der: “Flawed Saviours: the Myths of Hindenburg and Pétain”. In: European History Quarterly 39.3 (2009), 439-444; Pyta, Wolfram: “Paul von Hindenburg als charismatischer Führer der deutschen Nation”. In: Möller, Frank (Ed.): Charismatische Führer der deutschen Nation. Munich 2004: De Gruyter, 119-122; Vogel-Walter, Bettina: D’Annunzio. Adventurer and Charismatic Leader. Frankfurt a. M. 2004: Lang. The soldierly collective became an important basis for legitimising the individual war hero.

The soldierly hero during the First World War was, however, not only endowed with new attributes derived from modern warfare. As Stefan Goebel shows, the image of the modern soldier, especially in British society, was shaped by notions of medieval chivalry. Even if chivalry in battle was no longer possible, the ideal of chivalrous behaviour remained an important component of idealised notions of the soldier in British society. Soldierly heroism thus saw a shift from action – such as in a victorious battle or duel – to character. The First World War also led to soldierly heroism transcending class boundaries. Using the example of ‘chivalry’, one can see that on a rhetorical level, national virtues were glorified which applied equally to all those who had fallen.30Goebel, Stefan: The Great War and Medieval Memory. War, Remembrance and Medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914–1940. Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press, 188-230.

3.4. Mechanised chivalry

While it was only possible in very few cases to portray individual front-line soldiers as heroes, in other theatres of battle people were found who seemed more suitable for ⟶heroization in the media. Above all, aviation offered the possibility of giving military heroism a face again, thus counteracting the anonymisation and disillusionment of an industrialised war. “Heroes of the air” such as Gabriele D’Annunzio, Manfred von Richthofen or Georges Guynemer once again succeeded in reviving earlier notions of military heroism through an appropriate media staging.31Fritzsche, Peter: A Nation of Fliers. German Aviation and the Popular Imagination. Cambridge 1992: Harvard University Press, 59-101; Pernot, François: “Guynemer, or the myth of the individualist and the birth of group identity”. In: Revue Historique des Armées. 2 (1997), 31-46; Wilkin, Bernard: “Aviation and Propaganda in France during the First World War”. In: French History 28.1 (2014), 43-65; Schilling, “Kriegshelden”, 2002, 126-168. At the same time, they represented an extraordinary modernity, for the mastery of aircraft stood for not only mobility and overcoming the limits of space and time, but also for the triumph of man over nature. In many ways, the competition in the skies offered a counter-image to the nameless dead on the battlefields and made war meaningful again.32Esposito: “‘Über keinem Gipfel ist Ruh’”, 2006. Submarine captains occupied a similar position in media representation, but never achieved the popularity of fighter pilots.33Schneider: “Heldenkult”, 2009.

3.5. Soldier-heroes after the ‘Great War’

The soldierly hero was a deeply ambivalent and literally fractured figure after the First World War. On one hand, all post-war societies drew a large part of their legitimacy from the fallen soldiers, who without exception were declared heroes who had sacrificed themselves for their fatherland. On the other hand, all post-war societies had to deal with the constant presence of the surviving soldiers. Many of them were physically scarred by the war, missing limbs or with facial injuries, and were a pervasive reminder of the horrors of war. Their presence was difficult to reconcile with the fallen who were imagined as heroic.34Becker, Jean-Jacques / Berstein, Serge: Victoire et frustrations 1914–1929. Paris 1990: Seuil, 165-169; Kienitz: Beschädigte Helden, 2003; Ulrich, Bernd: “‘…als wenn nichts geschehen wäre.’ Anmerkungen zur Behandlung der Kriegsopfer während des Ersten Weltkriegs”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (Eds.): “Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch…” Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs. Essen 1993: Fischer, 115-129.

Even if the survivors were not forgotten, a notion of soldierly heroism that remained attached to the ‘Great War’ dominated. The sacrifice of millions of soldiers did not, in a sense, allow the trench hero to lose his hegemonic position in the collective memory of nations. Although attempts were made, especially by the left-wing political spectrum, to popularise a pacifist type of soldier, the image of the front-line soldier fighting for the fatherland dominated the interwar period.35Prost, Antoine: Les Anciens Combattants, 1914–1939. Paris 1977: Presses de Sciences Po. For example, at the victory celebrations and the tributes to the three marshals of France, Joseph Joffre, Ferdinand Foch and Philippe Pétain, in Paris, it was stipulated that under no circumstances should the impression be given that these three were greater than the fallen soldiers.36The Parisian deputy M. Deville thus emphasised: “Pour les ‘Poilus’ on ne fera jamais trop…, jamais assez.” (“For the ‘poilus’ you can never do too much…, never enough.”) Vgl. Weiss, René (Chef du Cabinet du Président du Conseil Municipal de Paris): La ville de Paris et les fêtes de la victoire. 13–14 juillet 1919. Paris 1920: Imprimerie Nationale, 4. But the heroic sacrifice of the fallen was not the only central motif in the heroization of soldiers. At the other end of the spectrum of memories of the soldiers of the First World War was an exaggeration of the experience on the front that sometimes seemed religious. Such an emphasis on the heroic struggle and the community at the front was intended to release these soldiers from their victim role and spread the exemplary ideal of a front-line fighter that could be transferred to civilian society. Pacifist appeals in the name of the Unknown Soldier and nationalist-militarist ones in the name of the front-line fighters stood for the two extreme poles of remembrance of the soldiers of the First World War.37Bergonzi, Bernard: Heroes’ Twilight. A Study of the Literature of the Great War. Basingstoke/London 1980: Macmillan, 183-186; Brückner, Florian: In der Literatur unbesiegt: Werner Beumelburg (1899–1963) – Kriegsdichter in der Weimarer Republik und im Nationalsozialismus. Dissertation, Universität Münster 2017; Colin, Geneviève / Becker, Jean-Jacques: “Les écrivains, la guerre de 1914 et l’opinion publique”. In: Relations internationales 24 (hiver 1980), 425-442; Erll, Astrid: Gedächtnisromane. Literatur über den Ersten Weltkrieg als Medium englischer und deutscher Erinnerungskulturen in den 1920er Jahren. Trier 2003: WVT, 289-297.

The public and the official discourses of remembrance also offered post-war societies the possibility of self-assurance through the evocation of chivalric attributes, irrespective of the interpretation over the soldiers’ sovereignty. Chivalric symbolic language suggested that the soldiers had not been touched by the brutality of war, that it had not turned them into cold-blooded murderers. Chivalric attributes helped to contain this potential post-war moral dilemma.38Goebel: “The Great War and Medieval Memory”, 2007, 230.

3.6. Soldierly heroism in the remembrance culture of the post-war period

In almost all nations, monuments to this new heroic figure were erected at the beginning of the 1920s. (See fig. 5.) The forms of commemoration for the fallen of the First World War were largely similar. For example, the common soldier who had been given his own grave was often commemorated; names were rarely listed by rank, resulting in a symbolic equality of the dead. Moreover, similarities in symbolism and imagery prevailed, so that one can perceive a uniform, European commemoration of the fallen that expressed similar ideas of soldierly heroism.39Janz, Oliver: Das symbolische Kapital der Trauer. Nation, Religion und Familie im italienischen Gefallenenkult des Ersten Weltkriegs. Tübingen 2009: Niemeyer, 1-3; Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 9-20; Prost, Antoine: “Les monuments aux morts”. In: Nora, Pierre (Ed.): Les Lieux de mémoire. I. La République. Paris 1984: Gallimard, 195-228; Becker, Annette: Les monuments aux morts: patrimoine et mémoire de la Grande Guerre. Paris 1988: Errance; Winter, Jay: Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning. The Great War in European cultural history. Cambridge 1995: Cambridge University Press.

The figure of the Unknown Soldier not only served as a focus for national mourning and to retrospectively legitimise the war victims, it also contributed to perpetuating a certain type of soldier-hero. The image of the front-line soldier who sacrificed his life for his fatherland in the trenches shaped the interwar period. In this regard, Bernd Hüppauf notes that, at least in the German case, two mutually exclusive war myths persisted: On the one hand, the “myth of heroism and sacrifice” of the Langemarck myth, which mainly inspired conservatives and nationalists. On the other, an “aggressive myth with futuristic and nihilistic features”, as epitomised in the material battles of Verdun in 1916. The Langemarck myth had kept alive and glorified the soldierly heroes with the ideals of chivalry and heroic sacrifice, whereas the Verdun myth had presented man as raw material, shaped in the highly organised, amoral and compassionless war. While the Langemarck myth essentially served the retrospective heroization of the fallen, the Verdun myth prospectively formed the ideological foundation of a “new man” in the age of mass war, which was later to be taken up by the Nazis.40Hüppauf, Bernd: “Schlachtenmythen und die Konstruktion des ‘Neuen Menschen’”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (Eds.): “Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch…” Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs. Essen 1993: Fischer, 43-84.

3.7. Freedom fighters as soldiers

But there were also forms of soldierly heroism that were not based only on the experiences of the First World War. In large parts of Europe, the fighting did not end in November 1918, but was continued by irregular units. In Germany, for example, Freikorps fighters who were still under arms in the disputed border areas between Germany and Poland until 1919 could be placed in a tradition with the soldiers of the Great War. During the phase of disputed nation-state foundations and unclear territorial allocations, individual freedom fighters were also assigned soldierly attributes throughout Europe. For example, Albert Leo Schlageter, who was sentenced to death during the occupation of the Ruhr, the irredentist Cesare Battisti, who came from South Tyrol, or the medical student Kevin Barry, who was executed in the Irish Civil War in 1920, could be portrayed and glorified as symbols of soldierly sacrifice for the fatherland.41Doherty, Martin A.: “Kevin Barry and the Anglo-Irish Propaganda War”. In: Irish Historical Studies 32 (2001), 217-231; Zwicker, Stefan: “Nationale Märtyrer”: Albert Leo Schlageter und Julius Fucik. Heldenkult, Propaganda und Erinnerungskultur. Paderborn 2006: Schöningh, 87-99, 252-259. In the post-war period, the boundaries between soldier-heroes and freedom fighters blurred accordingly.

4. References

- 1Schilling, René: “Kriegshelden”. Deutungsmuster heroischer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1813–1945. Paderborn 2002: Schöningh; Wulff, Aiko: “‘Mit dieser Fahne in der Hand’. Materielle Kultur und Heldenverehrung 1871–1945”. In: Historical Social Research 34/4 (2009), 343-355.

- 2Voss, Dietmar: “Heldenkonstruktionen. Zur modernen Entwicklungstypologie des Heroischen”. In: KulturPoetik/Journal for Cultural Poetics 11 (2011), 181-202.

- 3Esposito, Fernando: “‘Über keinem Gipfel ist Ruh’. Helden- und Kriegertum als Topoi medialisierter Kriegserfahrungen deutscher und italienischer Flieger”. In: Kuprian, Hermann (Ed.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung. Innsbruck 2006: Wagner, 73-90.

- 4Ven, Hans van de: “A hinge in time: the wars of the mid nineteenth century”. In: Chickering, Roger / Showalter, Dennis / Ven, Hans van de (Eds.): The Cambridge History of War: War and the Modern World. Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, 16-44.

- 5Drévillon, Hervé: L’Individu et la Guerre. Du chevalier Bayard au Soldat inconnu. Paris 2013: Seuil, 215-216, 239-250.

- 6Drévillon: L’Individu et la Guerre, 2013, 215-216.

- 7Chickering, Roger: “War, society, and culture, 1850–1914: the rise of militarism”. In: Chickering, Roger / Showalter, Dennis / Ven, Hans van de (Eds.): The Cambridge History of War: War and the Modern World. Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, 119-141, 120-122.

- 8Chickering: “War, society, and culture”, 2012, 124-125.

- 9Vogel, Jakob: “Der ‘Folklorenmilitarismus’ und seine zeitgenössische Kritik: Deutschland und Frankreich, 1871–1914”. In: Wette, Wolfram (Ed.): Militarismus in Deutschland 1871 bis 1945. Zeitgenössische Analysen und Kritik. Münster 1999: LIT, 277-292.

- 10Daniel, Ute: “Der Krimkrieg 1853–56 und die Entstehungsgeschichte medialer Kriegsberichterstattung”. In: Daniel, Ute (Ed.): Augenzeugen. Kriegsberichterstattung vom 18. zum 21. Jahrhundert. Göttingen 2006: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 40-67.

- 11Figes, Orlando: Crimea. The last Crusade. London 2011: Allen Lane, 467-472.

- 12Cf. for example: Steinsieck, Andreas: “Ein imperialistischer Medienkrieg. War correspondents in the South African War (1889-1902)”. In: Daniel, Ute (Ed.): Augenzeugen. War Reporting from the 18th to the 21st Century. Göttingen 2006: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 87-112.

- 13In Rudyard Kipling’s eponymous poem from 1890, a fictitious “Tommy” addresses the inherent ambiguity of being ascribed heroic status while still being treated like an ordinary soldier: “O it’s ‘Thin red line of ’eroes’ when the drums begin to roll. / We aren’t no thin red ’eroes, nor we aren’t no blackguards too, / But single men in barricks, most remarkable like you; … “ Online at: https://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poem/poems_tommy.htm (accessed 2022-12-21).

- 14The Iron Cross, endowed in Prussia in 1813, was intended not only to strengthen soldiers’ ties with the army, but also their willingness to go to war for their nation. Clark, Christopher: Preußen. Aufstieg und Niedergang 1600–1947, Munich 2007: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 434-435

- 15Figes: “Crimea”, 2011, 472.

- 16Figes: “Crimea”, 2011, 472.

- 17Becker, Frank: “Deutschland im Krieg von 1870/71 oder die mediale Inszenierung der nationalen Einheit”. In: Daniel, Ute (Ed.): Augenzeugen. Kriegsberichterstattung vom 18. zum 21. Jahrhundert. Göttingen 2006: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 68-86.

- 18Frevert, Ute: “Herren und Helden. Vom Aufstieg und Niedergang des Heroismus im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert”. In: Dülmen, Richard van (Ed.): Erfindung des Menschen. Schöpfungsträume und Körperbilder 1500–2000. Vienna/Cologne /Weimar 1998: Böhlau, 323-344.

- 19Carchidi, Victoria: Creation out of the void: The making of a hero, an epic, a world: T. E. Lawrence, (Dissertation University of Pennsylvania 1987). Ann Arbor 1987: UMI Dissertation Services. Online at: https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI8804889 (accessed 2023-01-11); Korda, Michael: Hero. The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia. New York et al. 2010: Harper.

- 20Capdevila, Luc / Voldman, Danièle: War Dead. Western Societies and the Casualties of War. Edinburgh 2006: Edinburgh University Press, 10-12.

- 21Harari, Yuval N.: The Ultimate Experience. Battlefield Revelations and the Making of Modern War Culture, 1450–2000. Basingstoke 2008: Palgrave Macmillan.

- 22Frevert: “Herren und Helden”, 1998, 339-340.

- 23Kienitz, Sabine: Beschädigte Helden. Kriegsinvalidität und Körperbilder 1914–1923. Paderborn 2003: Schöningh, 79-94.

- 24Schnyder, Peter: “Erlösung von der Medialität? ‘Held’ und ‘neuer Mensch’ in der Kriegsrhetorik von Simmel und Sombart”. In: Baumgartner, Stephan / Gamper, Michael / Wagner, Karl (Eds.): Der Held im Schützengraben. Führer, Massen und Medientechnik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Zürich 2014: Chronos, 29-50.

- 25Daniel, Ute: “Informelle Kommunikation und Propaganda in der deutschen Kriegsgesellschaft”. In: Quandt, Siegfried / Schichtel, Horst (Eds.): Der Erste Weltkrieg als Kommunikationsereignis. Gießen 1993: Universität Gießen FB Fachjournalistik, 76-93; Forcade, Olivier: “Information, censure et propagande”. In: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques (Eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, 1914–1918: histoire et culture. Paris 2004: Bayard, 451-466; Verhey, Jeffrey: “Krieg und geistige Mobilmachung: Die Kriegspropaganda”. In: Kruse, Wolfgang (Ed.): Eine Welt von Feinden. Der Große Krieg 1914–1918. Frankfurt a. M. 1997: Fischer, 177-178; Winter, Jay: “Propaganda and the mobilization of consent”. In: Strachan, Hew (Ed.): The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, Oxford 2000: Oxford University Press, 25-40.

- 26Schneider, Gerhard: “Heldenkult”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (Eds.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2009: Schöningh, 550-551.

- 27Schneider: “Heldenkult”, 2009, 550-551.

- 28Ackermann, Volker: “‘Ceux qui sont pieusement morts pour la France…’ Die Identität des Unbekannten Soldaten”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 281-314; Koselleck, Reinhart: “Einleitung”. In: Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 9-20.

- 29In France, for example, a heroic figure like Philippe Pétain was distinguished by his close relationship with the soldiers under his command, Paul von Hindenburg was endowed with soldierly attributes, Gabrielle D’Annunzio was regarded as the epitome of bravery and masculinity. Gildea, Robert / Goltz, Anna von der: “Flawed Saviours: the Myths of Hindenburg and Pétain”. In: European History Quarterly 39.3 (2009), 439-444; Pyta, Wolfram: “Paul von Hindenburg als charismatischer Führer der deutschen Nation”. In: Möller, Frank (Ed.): Charismatische Führer der deutschen Nation. Munich 2004: De Gruyter, 119-122; Vogel-Walter, Bettina: D’Annunzio. Adventurer and Charismatic Leader. Frankfurt a. M. 2004: Lang.

- 30Goebel, Stefan: The Great War and Medieval Memory. War, Remembrance and Medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914–1940. Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press, 188-230.

- 31Fritzsche, Peter: A Nation of Fliers. German Aviation and the Popular Imagination. Cambridge 1992: Harvard University Press, 59-101; Pernot, François: “Guynemer, or the myth of the individualist and the birth of group identity”. In: Revue Historique des Armées. 2 (1997), 31-46; Wilkin, Bernard: “Aviation and Propaganda in France during the First World War”. In: French History 28.1 (2014), 43-65; Schilling, “Kriegshelden”, 2002, 126-168.

- 32Esposito: “‘Über keinem Gipfel ist Ruh’”, 2006.

- 33Schneider: “Heldenkult”, 2009.

- 34Becker, Jean-Jacques / Berstein, Serge: Victoire et frustrations 1914–1929. Paris 1990: Seuil, 165-169; Kienitz: Beschädigte Helden, 2003; Ulrich, Bernd: “‘…als wenn nichts geschehen wäre.’ Anmerkungen zur Behandlung der Kriegsopfer während des Ersten Weltkriegs”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (Eds.): “Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch…” Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs. Essen 1993: Fischer, 115-129.

- 35Prost, Antoine: Les Anciens Combattants, 1914–1939. Paris 1977: Presses de Sciences Po.

- 36The Parisian deputy M. Deville thus emphasised: “Pour les ‘Poilus’ on ne fera jamais trop…, jamais assez.” (“For the ‘poilus’ you can never do too much…, never enough.”) Vgl. Weiss, René (Chef du Cabinet du Président du Conseil Municipal de Paris): La ville de Paris et les fêtes de la victoire. 13–14 juillet 1919. Paris 1920: Imprimerie Nationale, 4.

- 37Bergonzi, Bernard: Heroes’ Twilight. A Study of the Literature of the Great War. Basingstoke/London 1980: Macmillan, 183-186; Brückner, Florian: In der Literatur unbesiegt: Werner Beumelburg (1899–1963) – Kriegsdichter in der Weimarer Republik und im Nationalsozialismus. Dissertation, Universität Münster 2017; Colin, Geneviève / Becker, Jean-Jacques: “Les écrivains, la guerre de 1914 et l’opinion publique”. In: Relations internationales 24 (hiver 1980), 425-442; Erll, Astrid: Gedächtnisromane. Literatur über den Ersten Weltkrieg als Medium englischer und deutscher Erinnerungskulturen in den 1920er Jahren. Trier 2003: WVT, 289-297.

- 38Goebel: “The Great War and Medieval Memory”, 2007, 230.

- 39Janz, Oliver: Das symbolische Kapital der Trauer. Nation, Religion und Familie im italienischen Gefallenenkult des Ersten Weltkriegs. Tübingen 2009: Niemeyer, 1-3; Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink, 9-20; Prost, Antoine: “Les monuments aux morts”. In: Nora, Pierre (Ed.): Les Lieux de mémoire. I. La République. Paris 1984: Gallimard, 195-228; Becker, Annette: Les monuments aux morts: patrimoine et mémoire de la Grande Guerre. Paris 1988: Errance; Winter, Jay: Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning. The Great War in European cultural history. Cambridge 1995: Cambridge University Press.

- 40Hüppauf, Bernd: “Schlachtenmythen und die Konstruktion des ‘Neuen Menschen’”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (Eds.): “Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch…” Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs. Essen 1993: Fischer, 43-84.

- 41Doherty, Martin A.: “Kevin Barry and the Anglo-Irish Propaganda War”. In: Irish Historical Studies 32 (2001), 217-231; Zwicker, Stefan: “Nationale Märtyrer”: Albert Leo Schlageter und Julius Fucik. Heldenkult, Propaganda und Erinnerungskultur. Paderborn 2006: Schöningh, 87-99, 252-259.

5. Selected literature

- Baumgartner, Stephan / Gamper, Michael / Wagner, Karl (Eds.): Der Held im Schützengraben. Führer, Massen und Medientechnik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Zürich 2014: Chronos.

- Esposito, Fernando: “‘Über keinem Gipfel ist Ruh’. Helden- und Kriegertum als Topoi medialisierter Kriegserfahrungen deutscher und italienischer Flieger”. In: Kuprian, Hermann (Ed.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung. Innsbruck 2006: Wagner, 73-90.

- Frevert, Ute: “Herren und Helden. Vom Aufstieg und Niedergang des Heroismus im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert”. In: Dülmen, Richard van (Ed.): Erfindung des Menschen. Schöpfungsträume und Körperbilder 1500–2000. Vienna/Cologne/Weimar 1998: Böhlau, 323-344.

- Goebel, Stefan: The Great War and Medieval Memory. War, Remembrance and Medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914–1940. Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Harari, Yuval N.: The Ultimate Experience. Battlefield Revelations and the Making of Modern War Culture, 1450–2000. Basingstoke 2008: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hüppauf, Bernd: “Schlachtenmythen und die Konstruktion des ‘Neuen Menschen’”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (Eds.): Keiner fühlt sich mehr als Mensch… Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs. Essen 1993: Fischer, 43-84.

- Kienitz, Sabine: Beschädigte Helden. Kriegsinvalidität und Körperbilder 1914–1923. Paderborn 2003: Schöningh.

- Koselleck, Reinhart / Jeismann, Michael (Eds.): Der politische Totenkult. Kriegerdenkmäler in der Moderne. Munich 1994: Fink.

- Prost, Antoine: “Les monuments aux morts”. In: Nora, Pierre (Ed.): Les Lieux de mémoire. I. La République. Paris 1984: Gallimard, 195-228.

- Schilling, René: “Kriegshelden”. Deutungsmuster heroischer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1813–1945. Paderborn 2002: Schöningh.

- Voss, Dietmar: “Heldenkonstruktionen. Zur modernen Entwicklungstypologie des Heroischen”. In: KulturPoetik/Journal for Cultural Poetics 11 (2011), 181-202.

- Wulff, Aiko: “‘Mit dieser Fahne in der Hand’. Materielle Kultur und Heldenverehrung 1871–1945”. In: Historical Social Research 34.4 (2009), 343-355.

- Zwicker, Stefan: “Nationale Märtyrer”. Albert Leo Schlageter und Julius Fucik. Heldenkult, Propaganda und Erinnerungskultur. Paderborn 2006: Schöningh.

6. List of images

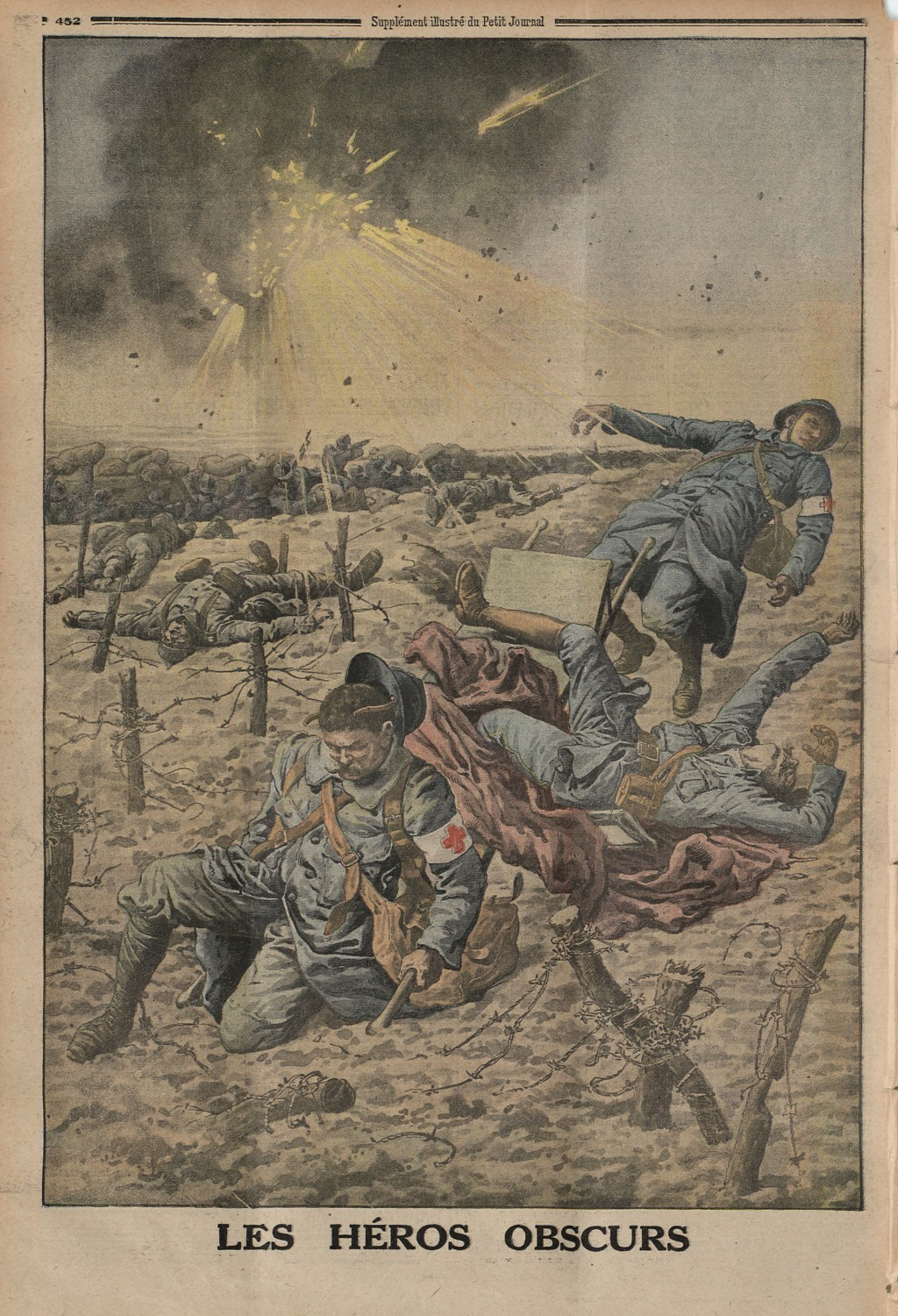

- “Les héros obscurs” (detail), back cover of the Supplément illustré du Petit Journal, 26 March 1916.Licence: Public domain

- 1Carl Röchling: “Episode from the Battle of Gravelotte (Death of Major von Hadeln on 18 August 1870)”, 1897, oil on canvas, 115 cm × 181 cm, Berlin, Deutsches Historisches Museum, Inv. No. 1988/99.Source: Bartmann, Dominik / Werner, Anton von (Eds.): Anton von Werner. Geschichte in Bildern. München 1993: Hirmer, 97, No. 293, Fig. 61.Licence: Public domain

- 2The Guards Crimean War Memorial, 1861, London, after a design by John Henry Foley and Arthur George Walker.Source: User:Qmin / Wikimedia CommonsLicence: Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0

- 3“Les héros obscurs”, back cover of the Supplément illustré du Petit Journal, 26 March 1916Licence: Public domain

- 4Frank Hurley: “The morning after the first battle of Passchendaele showing Australian Infantry wounded around a blockhouse near the site of Zonnebeke Railway Station, October 12, 1917.”Licence: Public domain

- 5Monument aux morts de la guerre 1914–1918, Hendaye, 1921, designed and executed by Henry Martinet and Louis Adamski. Bronze statue by Paul Ducuing. Inscription: “Aux héros hendayais de la Grande Guerre.”Licence: Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0

![Frank Hurley: „The morning after the first battle of Passchendaele [Passendale] ...“](https://www.compendium-heroicum.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/4_Hurley_The-morning_after_the_first_battle_of_Passchendaele_1917.jpg)